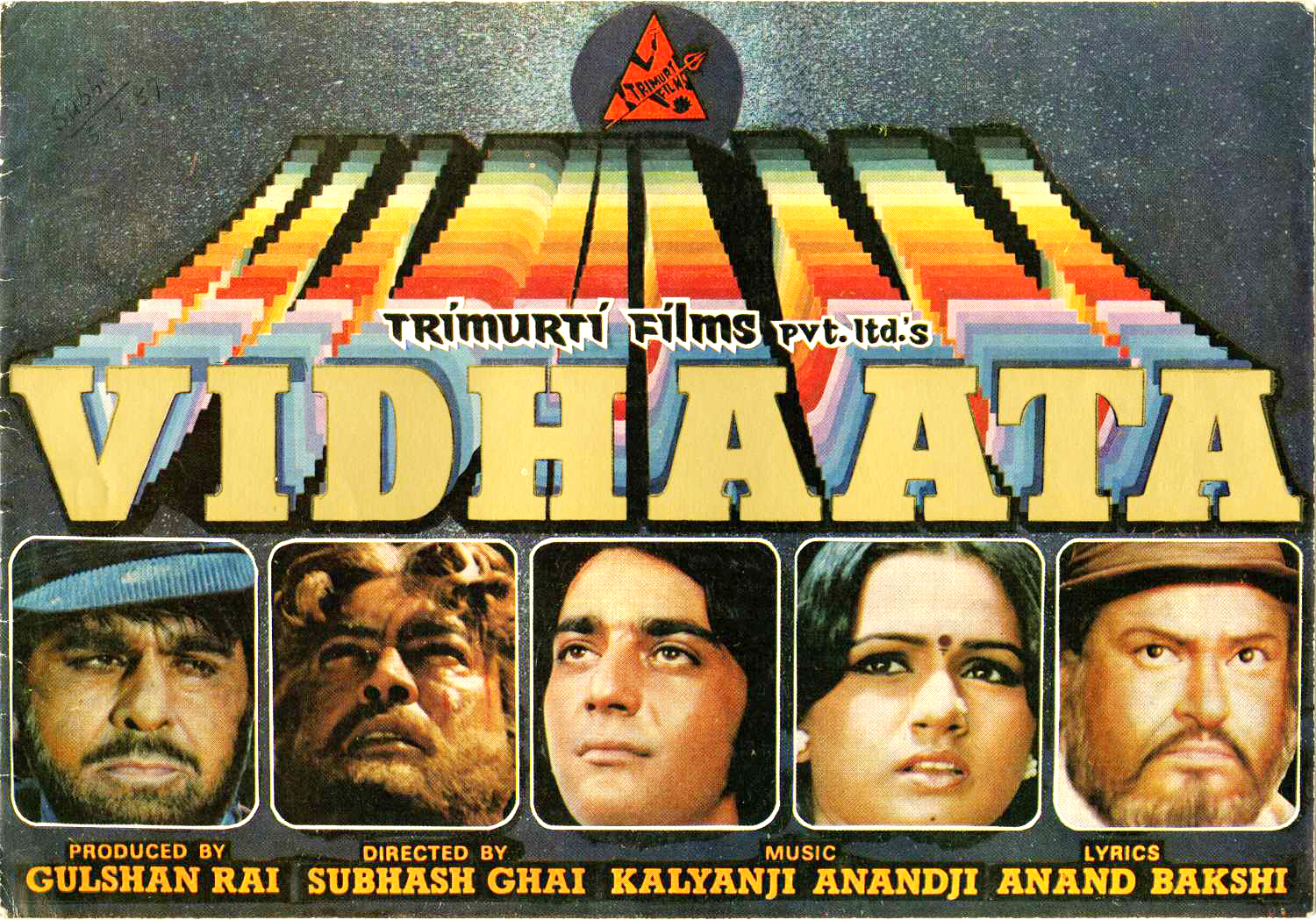

Bollywood posters at Churchgate Station in Mumbai, 1997, photo by Jonathan Torgovnik/Getty

Bollywood is the hindi analog of Hollywood. This is usually the name of the film studios of Mumbai, formerly Bombay. This is not the only branch of Indian cinema: there are also Tollywood, Kollywood, and other studios making movies in regional languages. But the brightest colors, the most famous actors, and the highest box office are, of course, Bollywood. Film critic Alexei Vasiliev has undertaken to tell the never-ending story of Bollywood for Qalam, choosing a different emotion and the most iconic character-actor for each era.

From the twisted alleyways lined with wooden houses, past street beggars and boys in tattered t-shirts stealing apples, emerges the first great hero of Bombay cinema, destined to plant it firmly on the map of the world. He walks with a duck-like gait under the faint glow of street lamps, the black-and-white archaic filmmaking making him appear even more fragile. He wears a worn-out cast-off jacket, wide barely ankle’s length trousers, a slightly tilted floppy hat, a thin mustache reminiscent of a Nazi officer, and a stick over his shoulder with a small bundle containing all his worldly possessions. He walks and sings: "I am a vagabond, a vagabond, and no one awaits me anywhere."

Raj Kapoor's film "Awaara" (The Vagabond, 1951) was presented at the Cannes Film Festival competition in 1953, paving the way for a decade of these peculiar, lengthy, and eccentric films where the heroes spontaneously broke into song and dance to earn a place in prestigious international film festivals. The prominent French film critic and historian Georges Sadoul immediately dubbed Kapoor as the "Indian Chaplin," a comparison that required no special insight and was evident. In this film, Kapoor walked like Chaplin, dressed comically like Chaplin, and his character was an unprivileged wanderer, much like Charlie, good-natured and trusting, perhaps too trusting to find his place in the world of thieves but still pure enough to realize and break free from the criminal environment, landing himself in the dock. Just like Chaplin.

The poignant sentimentality of the vagabond's hopeless love for the girl in white ribbons playing the piano, whom he fell for when he was just a schoolboy, coexisted with a touch of buffoonery, pulling the noses of an incompetent police officer and jolly fat ladies.

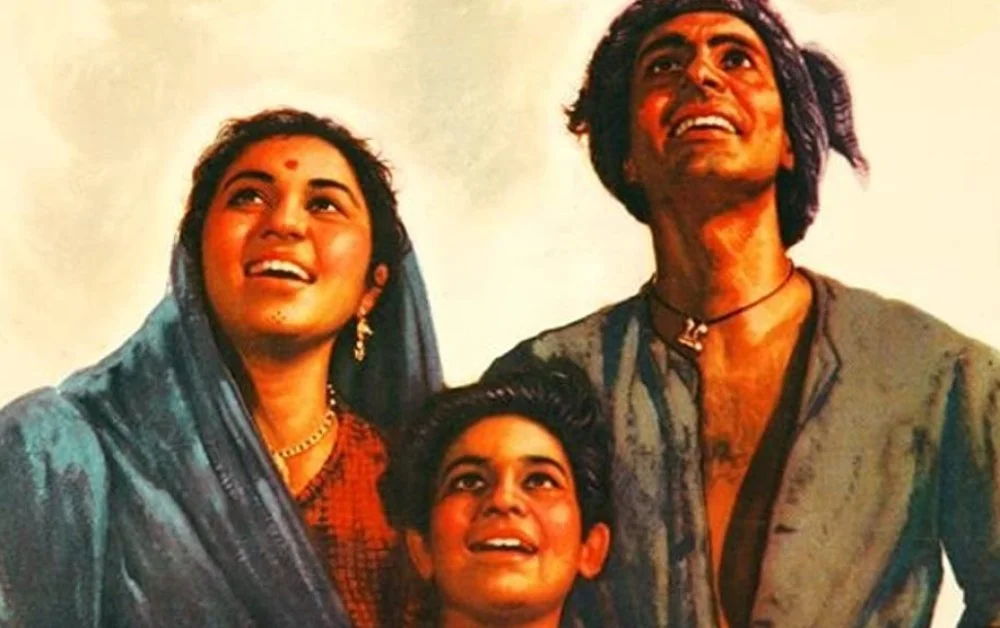

"Awaara" Raj Kapoor, 1951/Wikimedia Commons

Chaplin himself had already embraced gray hair and shed tears over the decline of the theatrical comedian in his latest "Limelight" (1952). However, the world tends to get most nostalgic about favorite things from 20-30 years ago. Kapoor resurrected the beloved Charlie of the days of "City Lights" (1931) and "Modern Times" (1936). The fact that this resurrection happened in the forms and images of an almost unknown but evidently provincial and exotic cinema only added fuel to the fire: the open, emotional performance and dramaturgy, the cardboard music hall feel of certain song sequences, the presentation itself, seemingly tailored for naive children who need everything spelled out, unintentionally served as elements that future critics would term postmodern irony, without which retro films cannot be successful.

After Cannes, the film and its creator embarked on a world tour: England, America, and Japan. Everywhere, they drove the crowds to laughter and tears with their futile nostalgia for Charlie. Kapoor, who elevated the lost innocence of old cinema to the power of his own stylized naivety, could well be called the "Almodovar" or "Tarantino by chance" of his time.

"Awaara" 1951 /Wikimedia Commons

But was it really just chance? When Kapoor’s entourage arrived in Moscow in the autumn of 1954 with "The Tramp," joined by then Bombay superstar Nargis, who played the role of the "girl with the white bows," along with the screenplay writer Khwaja Ahmad Abbas and four other Bombay films with all their creators - veteran Soviet film director Grigory Roshal made a much more subtle observation than the obvious comparison with Chaplin. In his article "Strengths and Weaknesses of Indian Films," he noted that "Chaplin's influence on Kapoor is undoubtedly present" and added: "In 'The Tramp,' there is also the undeniably significant influence of Douglas Fairbanks. Here, at times, there's a kind of "toothy charm" reminiscent of the famous silent film hero of American cinema, a slight tendency to overly revel in own’s charm, irresistibility, and te like.

Roshal, perhaps, did not realize on how many levels his statement works in relation to Kapoor. On the surface - contrary to his initially absurd image, he showcased sex appeal, without which a star is just not a star. At least not a "hero." Raj Kapoor created himself as a star. In the sense that he was his own director, "The Tramp" marked his third self-produced film where he played the lead role, and it was through films where he cast himself that he garnered widespread fame across India. He had a keen understanding that in order to portray a hero effectively, it was crucial to highlight his youthful exuberance, rendering him physically appealing to his audience. This concept is evident, at the very least, in his costume choices, which revolutionized Indian film fashion to such an extent that other actors didn't immediately embrace the same approach.

Before Indian film heroes either walked around in traditional Indian attire - a long tunic and a loincloth-dhoti, or in European suits, or, at most, in a maharaja's turban, but always securely buttoned up and covered. Kapoor not only bared his ankles but, by initially dressing his character in rags, he set the tone. In romantic scenes, he was the first in India to flaunt the casual style - striped T-shirts with short sleeves. He was very attractive in his youth, and he knew how to dress against the local standards to make the audience simply want to cuddle him.

"Shree 420". Raj Kapoor, 1955/Wikimedia Commons

Just as he flaunted a new style in clothing, Raj Kapoor also flaunted his cinematic style, borrowing texture not so much from Chaplin but from the trendiest movement of that time - Italian neorealism. Raj Kapoor came from a family of actor Prithviraj Kapoor, who became a star back in 1931, starring in the first Indian sound film, "Alam Ara" (1931). In "The Tramp," Kapoor's father played the role of a prosecutor who accuses Raj and eventually turns out to be his lost father. Kapoor Sr. was obsessed with theater, but he quickly realized that real money would be in cinema. His calculation proved correct, and in 1944, with the earnings from the film industry, he was able to open the "Prithvi Theatre" right in the Juhu neighborhood near Bombay airport, where all film studios and bungalows of their creators are concentrated. The theatre played a significant role in promoting both advanced Indian drama and European classics. Raj was wealthy and cultured; he received his education in London. His first two directorial works were quite different from "The Tramp."

His first film, "Infernal Passion" (Aag, 1948), begins with a jolting scene: a bride's horrified scream upon seeing her groom's disfigured and burned face for the first time on their wedding night. This indeed sets an intriguing thematic tone. The question of whether external beauty reflects inner beauty was one of the topics that occupied Kapoor throughout his life, and a later film on this theme, "Satyam Shivam Sundaram" (1978), featuring the disfigured face of the first disco-era beauty Zeenat Aman, had an even greater impact. His subsequent film, "Monsoon" (Barsaat, 1949), showcased Kapoor as an exceptionally realistic chronicler of the golden youth. He was intimately acquainted with this world, allowing his character to express lines to his friend like, "We are so distinct, yet so intimately connected and vital to each other, akin to a body and soul. Perhaps, we should seek one girl for both of us." This theme of a conventional love triangle, approached in a novel manner by Kapoor, carried forward into his movie "Sangam" (1964), a three-part color film featuring a global journey filmed in London, Paris, and the Alps. Similar to "The Tramp," it became one of Bombay's most acclaimed productions and initiated a new trend for "business trip" films.

The black and white film "Monsoon" is still captivating to watch in one go. Because the young Kapoor, only 24 years old at the time of the film's release, fearlessly addressed topics that were considered taboo not only in Indian cinema but in the entire film industry of that era. It also serves as an unmatched encyclopedia of cars, costumes, and pastimes that were popular among India’s “golden youth” at that time. After gaining independence, India, having freed itself from the British and left to its own devices, stopped insisting on national culture, which was highly esteemed in the pre-war period, and swiftly embraced Western styles. Moreover, having watched numerous quality Hollywood films in London, Kapoor found that all these artificial beauties seamlessly integrated into the natural splendor of the forest and lake landscapes. They harmonized with the glistening semi-shade cast by the tree canopies and the breezes, much like the inebriated antics of millionaires in George Cukor's movie "The Philadelphia Story" (1940).

According to the indian theatrical vedic tradition, the viewer should alternately experience nine moods, "rasas": love, humor, wonder, courage, calmness, anger, sadness, fear, and disgust.

Following the pattern common among all genius visionaries - and Kapoor was undeniably a virtuoso of style - he scattered his breakthroughs, integrating them as mere components of his films without elevating them to iconic status. Subsequently, others seized upon these thriving elements within his groundbreaking movies and evolved them into a distinct genre, giving rise to an entire movement.

The lifestyle of the golden youth, so effectively presented in "Monsoon," became the subject and essence of the subsequent film titled "Andaz" (1949). There, the luxurious life was openly savored, but unlike the sincere portrayal by an insider in Kapoor's films, it faced hypocritical criticism for the aspiration of girls from affluent families to adopt a Western approach to friendship and love. Again, as in "Monsoon," the film revolved around a love triangle, but with completely different conclusions: as if "Monsoon" were made by students (which, in essence, was almost the case), and "Andaz" by their teacher, an old maid. Interestingly, the apex of this triangle was played by the same Raj Kapoor and his now indispensable partner Nargis - the shot from "Monsoon," where Nargis, tilting her head backward, hangs from Raj's right hand while he holds a violin in his left hand, became the emblem of his own studio, "R.K. Films." The third participant was another important Bombay actor, Dilip Kumar, who we will discuss in detail in the next chapter.

However, "Andaz" is one of those films that exposed the Indian audience to the new hypocrisy of their native cinema. You might have observed that in Indian films, even before the studio emblem appears, something akin to an excise label that one might typically find on a wine bottle featuring handwritten dates is displayed on the screen. This was the permission stamp of the censorship committee, which gained full power in the late 1940s. The committee had existed since the late 1920s, but under British rule, censorship was purely political. Kissing scenes were not prohibited, and the films addressed the most sensitive topics, including venereal diseases. After the departure of the British, it was expected that there would be no censorship at all. However, the ideology of Mahatma Gandhi, which continued to be propagated by Jawaharlal Nehru after Gandhi's assassination in 1948, insisted on traditional values, including celibacy, which young men were expected to maintain during their studies. In principle, this ideology, though less militant, continues to be present in Bombay cinema to this day. "Andaz" taught Indians to read between the lines. It revealed the response to the allure of luxury and loose morals. However, during the premiere of the film in Bombay, the first modern cinema equipped with air conditioning and seats with velvet upholstery, appropriately named "Liberty," was opened. This event redefined the main expectation of going to a Bombay film for life - to immerse oneself for three hours in a luxurious film about the extravagant life in a posh movie theater.

Poster of the film "Andaz" 1949/Wikimedia Commons

In "The Tramp," a similar attraction also appeared, which would remain an obligatory complement to Bombay films until the 1980s, something that deserved all kinds of condemnation but whose announcement drew larger crowds than other "heroes." It was the cabaret girl who sometimes appeared just for one song, sometimes played a certain role in the plot, and if so, she invariably received a bullet or some other punishment. These girls sang in the most fashionable styles, baring themselves to the maximum, depending on what the censorship committee agreed to, enticingly waving glasses and bottles of alcohol (another semi-taboo of Indian society), and dancing provocatively. These songs, when included in the musical anthologies of Bollywood, evoked sweet dizziness.

Just as in each era in Bombay, there was a specific group of heroes and heroines, there was also a restricted pool of actresses considered for the roles of these cabaret beauties, each of them known for their vivacious nature and exceptional dancing prowess: Helen, Bindu, Aruna Irani, Padma Khanna. Speaking of their status, it is appropriate to quote Indian film journalist Ratna Rajai: "We went to the cinema every Friday, my dad, mom, and I. Every time a heroine appeared on the screen, my father would loudly ask, 'What's her name?' When Hema, Rekha, Rakhee, Jaya, or any of the queens of that time were on the screen, he didn't recognize any of them and would be furious with us and my mom. But as soon as the saxophone moaned, and a plump but elastic leg in fishnet stockings appeared on the screen ascending with the camera, bypassing the sparkling hips, gliding along the tantalizing waterfall of breasts, half-opened to emit temptation with cigarette smoke, my father would recline in his chair and not ask anything else - he knew: Helen, Padma, Aruna, Bindu."

In "The Tramp," Kapoor introduced the first of the splendid array of dancers - Kuku. As is typical of Kapoor, he simply presented her without judgment, bullets, or remorse, entertaining the audience with an energetic dance and the catchy song "One, two, three, look at Me." The fact that Kuku's appearance became just as much a signature of the film as the song of the Tramp himself is evidenced by the fact that during the triumphant days of the movie in the USSR - where 63.7 million tickets were sold - Russian “babushkas” adapted the lyrics of this very song to their own style. They bid farewell to the girls who were going to watch "The Tramp" for the tenth time with verses like "Raj Kapoor, look at these silly girls."

Actress Nargis and actors Raj Kapoor and Dilip Kumar 1949/Alamy

The success of "The Tramp" and Kapoor was phenomenal in all the countries that made up the USSR at that time. It was restored and re-released twice, in 1972 and 1987. The memory of it remains strong. Raj Kapoor, who became a regular guest at International Film Festivals in Asia, Africa, and Latin America in Tashkent, recounted in 1982 that Uzbek boys still ran after him, teasingly singing the Hindi song "Awaara Hoon." Much later, in 2009, I took the actor's son, Rishi Kapoor, who became a superstar in the 1970s, to an Azerbaijani restaurant, "Tales of the East," unexpectedly and unannounced during the day. The waiters recognized him instantly, and the manager started sharing stories about his father's visit to Baku and his friendship with Rashid Behbudov. Everyone wanted a group photo with Rishiji, and the photo was proudly displayed in the most prominent spot until the restaurant burned down.

What's the secret of such success? In the distorted Indian reality, we saw a glimpse of our own, not yet recovered from the war. This time, Kapoor skillfully reproduced the external features of neorealism, which gave the film a fashionable appearance. Neorealist films were highly popular at that time. Unlike India, where "Bicycle Thieves" was first seen only in 1952, Kapoor had already seen Italian films, understood their trend, and skillfully copied the techniques and shooting style. He even anticipated the "pink neorealism" - lighter, comedy-tinged films about poverty featuring voluptuous divas like Gina Lollobrigida and Sophia Loren, in which, as one Soviet critic aptly noted, even rags " looked picturesque." These films appeared after the release of "The Tramp," around the same time when Kapoor's film reached Cannes.

The second component of its success was the plot about an orphan finding his father. The war created so many "orphans in question" with missing soldiers, and the film's promise of such a reunion provided comfort. For Indians in 1951, this theme resonated deeply. After gaining independence on August 15, 1947, a bloody partition with Pakistan began, leading to massacres between Hindus and Muslims. Cities were in chaos, and martial law was declared. People ran back and forth, unsure of where the borders lay, and many never found out if their loved ones were alive or in which country they had ended up.

The third film vividly and in detail depicted the life of criminal gangs. In the USSR and during Stalin's time, there were plenty of prisoners, and after the all-union amnesty, which happened a year before the release of "The Tramp," they became even more abundant. The gangster Jaga aspired to become a criminal sex symbol, but even Kapoor, with his mustache, ranked not far behind. When my mother hung Kapoor's photo on her wall, her grandmother sincerely lamented that her schoolgirl granddaughter had become involved with a criminal.

Translation: If Kapoor used neorealism as his aesthetic foundation and Chaplin as his performance model, then in depicting the criminal underworld, he heavily drew from Western influences, with the style of French poetic realism playing a role perhaps even greater than film noir. Once again, what he created merely as a component of the film immediately turned into a separate genre, giving rise to gangster cinema that lasted in Indian cinema until the mid-1970s. The Tramp merely stumbled into the realm of criminal haunts, gambling dens, and cabarets, while Dev Anand, in the film "High Stakes" (Baazi, 1951), never managed to leave them. His character, a cardplayer, and partygoer, much like Raj, is unattached, but more so in an existential sense. He views life as if it were a roulette table, extracting winnings from the naive, steering clear of bigger criminals, and only shaking himself off and laughing when they eject him from the car into a puddle somewhere outside the city.

A shot from the film "Awaara". 1951/Alamy

He didn't seek love but virtuous and unvirtuous girls were drawn to him; the latter, after performing passionate dances, unlike Kuku from "The Tramp," would end with the shot of a bullet. Subsequent films, attempting to imitate Kapoor's style, once again fell into the trap of moralizing, dissecting him into fragments. In this depiction, akin to his hero's tilted cap, Dev Anand would continue to grace the screen for another twenty-five years in movies such as "Taxi Driver" (1954), "Kala Bazar" (1960), and "Heera Panna" (1973).

Soon, gangster films became a mandatory dish on the menu of any idol of the era: Dharmendra had "Phool Aur Patthar" (1966), Rajesh Khanna - "Roti" (1974), and so on. Truly, despite the uniformity of the plots, it will always be interesting to see how an actor, responding to the specific demands of the era with his appearance, manners, and playing style, leaves his mark on this inherently masculine territory.

"Taxi Driver", 1954/Wikimedia Commons

As you can see, Kapoor's films weren’t merely a source from which to extract quotes for inspiration – they gave rise to entire enduring trends. Themselves composed of such diverse elements, they seem to blend several distinct movies together, akin to a patchwork quilt. This allows Kapoor to be counted among the forefathers of masala films:i

However, by addressing this subject, we finally find a pretext to explain why we voluntarily omitted the entire period of Indian cinema before the country's independence. After all, the main features of Indian cinema - dances, and fights - became the subject of the first silent short films shot in India: "The Flower of Persia" (1898) and "The Wrestlers" (1899), respectively. From the moment of the release of the first Indian feature film, "Raja Harishchandra" (1913), local cinema enjoyed considerable demand, producing more films than any other country. In the very first sound film, songs were introduced, and in the second one, "Indra Sabha" (1932), various different researchers counted from 50 to 70 songs (although they were deceptive; it was a film in verses, and they considered instances when melodious recitation transitioned into song ).

Everyone knows that before the start of each film, viewers in India stand up and sing the national anthem, but few know that it is a song from the movie "Hamrahi" (1944), released three years before independence was proclaimed. Moreover, "The Tramp" wasn't Kapoor's first film to make waves abroad. Even prior to the war, India participated thrice in the prominent and then-singularly conducted film festival in Venice, returning twice with awards. And after the war, with the inception of the Cannes Film Festival, where a whopping 11 "Golden Palm Branches" were joyously bestowed, one of them found its way to India. Chetan Anand, the brother of the aforementioned Dev, carried it back for his film "Lower Town" (Neecha Nagar, 1946). This film combined, in the spirit of early post-war European cinema, somber romance with a social call to action. Even "The Tramp" wasn't the first Indian film to arrive in the USSR; preceding it were our melodramas depicting the plight of famine-stricken Bengal - "Children of the Soil" (Dharti Ke Lal, 1946) and "The Unprivileged" (Chinnamul, 1950). All of this holds true. However, "The Tramp" was the first film that audiences willingly watched. Because it was Bollywood.

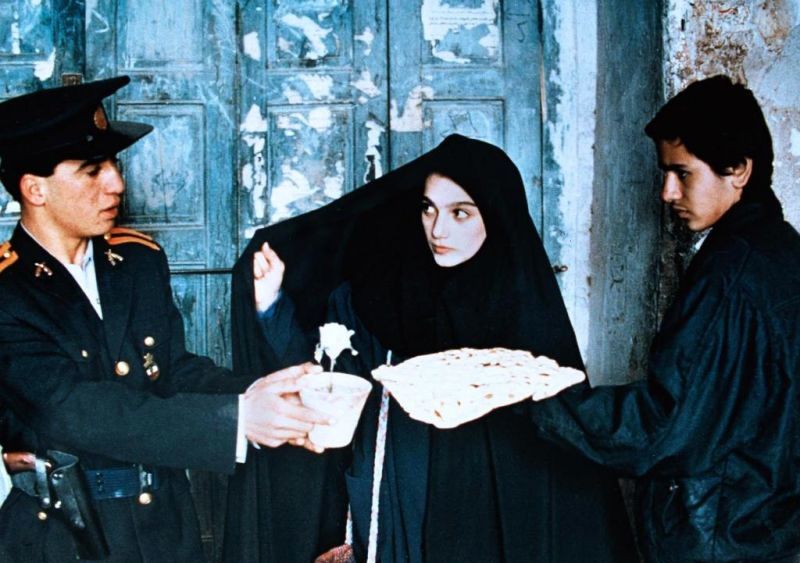

"Neecha Nagar" 1946/Wikimedia Commons

Translation: Furthermore, "The Tramp" wasn't Kapoor's first film abroad. Even before the war, India participated three times in the largest and only regularly held film festival in Venice, returning twice with awards. And after the war, when the Cannes Film Festival was established and 11 "Golden Palm Branches" were awarded with excitement, one of them was taken to India by Chetan Anand, Dev's mentioned brother, for the film "Lower Town" (Neecha Nagar, 1946). This film combined somber romance with a social call in the spirit of early post-war European cinema. Even "The Tramp" wasn't the first Indian film in the USSR; before it, melodramas about the hardships of famine-stricken Bengal - "Children of the Soil" (Dharti Ke Lal, 1946) and "The Unprivileged" (Chinnamul, 1950) were released. All true. But "The Tramp" was the first film that people willingly watched. Because it was Bollywood.

The cycle of articles is titled "The History of Bollywood" and not "The History of Indian Cinema," for good reason. Although the word "Bollywood," when it slipped from my tongue, elicited a disapproving reaction from diverse and quite critical film idols like Amitabh Bachchan and Rishi Kapoor: "It's an offensive and meaningless nickname invented in the West! There is no Bollywood, there is Indian cinema!" But to write a meaningful history of Indian cinema would require several volumes and a team of specialized experts.

Firstly, Indian cinema is a pure sum of regional cinematographies operating in their own languages, with their own stars, and catering to their respective audiences. They rarely exchange talents and even less frequently intersect in distribution and differ quite drastically. For instance, Bengal, the land of Tagore,i

Even Bombay cinema is not all Bollywood; there exists the Marathi-language film industry, closely tied to everyday life and realities. Strictly speaking, Bollywood is a conglomerate of Bombay film studios producing films in the national language, Hindi. These films enjoy nationwide distribution, and Hindi film stars are recognized and celebrated in every corner of the country, with their filmmakers having the most impressive budgets. However, in a metaphorical sense, Bollywood represents that part of the Bombay industry where masala films were born.

Masala refers to a mix of hot and spicy spices. A masala film is a three-hour spectacle that includes everything: romance, comedy, gangster film, adventure, action, and martial arts film as its base, and can include western, detective, science fiction, and industrial drama - depending on the authors' imagination and producers' funds. These genres within a single film may not overlap but appear sequentially as if the characters themselves jump from one genre and even one story to another. Masala films fully developed by the 1970s, which is attested by record box office collections. Their success is rooted in Indian theatrical Vedantic tradition and the concept of the nine Rasas, or emotions, that the audience must experience in turn: love, laughter, sorrow, anger, courage, fear, disgust, surprise, and tranquility. If any of these emotions is missing, the viewer will perceive the encounter with the dramatic work as incomplete - in other words, they will demand their money back.

The term "Bollywood" became popular in the early 21st century, when, from the mid-1990s, a team of nostalgic 30-year-old filmmakers recreated the golden formula of the 1970s at a new technical level, leading Indian cinema to penetrate the West. Here's a digest, and we will revisit each point in detail later.

Before gaining independence, Indian cinema was genre-separated. One of the films shown at the Venice Film Festival before the war was a pirate film about a female pirate ("Eternal Flame" / Amar Jyoti, 1936), a very specialized offering. Even such an authoritative researcher and connoisseur of Indian cinema, like Feroze Rangoonwalla, refers to the 1949 film "Shabnam" as the first masala film, where all the necessary mix of elements is present, familiar to Soviet audiences from films like "Eternal Love Story" (Dharam Veer, 1977) and "Like Three Musketeers" (Jagir, 1984) - Maharajas, viziers, masked avengers, prisons, beauties veiled in saris, armed soldiers with contemporary weapons, gypsies, and so on.

Let's take his word for it. In a sea of production like Indian cinema, where the number of films produced reached 950 in 1985, pinpointing the original film and being confident in one's assertion is nearly impossible.

Our hero, Raj Kapoor, during the time of "Shabnam," successfully experimented with synthesizing incompatible elements, and "The Tramp" was the most complete and organically blended combination of genres and styles. However, when he attempted to repeat the recipe in "Shree 420" (1955), the film had some success, but as a reviewer from "Art of Cinema" rightly noted, "it's like running into a doppelganger of your friend on the street – it looks like your friend, but it's not quite the same."

At the beginning of the film, Kapoor sang an epochal song reflecting his enthusiasm after the triumph with "The Tramp": "Dressed like a picture, I wear Japanese shoes, a large Russian hat, and an Indian soul." However, the film itself, composed of previous blocks, seemed to break down into a series of dragged-out medium-length films. For 45 minutes, the new protagonist engaged in a romance with a cabaret vamp portrayed by Nadira. Just as we were beginning to feel that we were watching a gangster movie, the film took a decisive turn towards political propaganda with strikes and rallies that continued for another half an hour, which was utterly unbearable. Today, it is simply impossible to watch.

Nargis in "Awaara" / Alamy

Nevertheless, Kapoor's social optimism after the release of "The Tramp" shaped the mood of Bombay cinema for five years. The curly-haired comedian Kishore Kumar emerged as a star, possessing a voice of remarkable depth and perfect pitch, ironically. While his clerks entertained the audience, experiencing misadventures with far-from-funny problems like unemployment ("Naukari" / "The Job," 1954), his songs deeply touched even the most insensitive viewers. Kumar was the last of the singing film stars. If the idol of the 1930s, Saigal, matched his nightingale-like singing with romantic heroes, Kumar's acting range and appearance confined him to comedy. As a result, he became one of the first legendary playback singers whose names started appearing in the credits.

The film characters split into the dramatic and musical performers. The playback singers were now stars themselves. Duos emerged. For Raj Kapoor, it was always Mukesh who sang, for Dilip Kumar – Mohammed Rafi. Kishore Kumar served Dev Anand. However, by the mid-1960s, this duality of "face - voice" dissolved. Kumar sang for anyone and everyone, including Amitabh Bachchan and Mithun Chakraborty. Moreover, within the same film, different songs for the same actor were sung by various singers, chosen based on how their voices would best highlight the song's favorable aspects. The movement towards masala-mix was irreversibly ongoing on this musical path.

All female actors , were voiced by just two sisters with very delicate voices: Lata Mangeshkar (for more lyrical songs) and Asha Bhosle (for cabaret numbers). Their dominance began in 1948 with the performance of the joking song "English Boys Have Gone Home" in the film "Majboor" (Forced). In 1952, as already mentioned, "The Bicycle Thieves" arrived in India, and the first international film festival was held there. The success was so colossal that for the next two years, the screens of the country were flooded with films about children who, like the comedies with Kishore Kumar, did not diminish or embellish the hardships of poor people wandering in search of sustenance through the big cities. They did not offer happy endings; instead, they left the characters at a crossroads. However, the charm of the children and the sense of the future that the mere sight of a child evoked made the audience leave the theaters with a hopeful feeling.

Many of these films were tremendously successful: "Do Bigha Zameen" (1953) went to Cannes and returned with an award, along with two newly established Bombay Oscars, the "Filmfare" awards, for Best Film of the Year and Best Direction (Bimal Roy). "Boot Polish" (1954) became the highest-grossing film of the year in India and also won three "Filmfare" awards the following year: Best Film of the Year, Best Cinematography, and Best Supporting Actor (David Abraham). The star of both films, the wide-eyed 12-year-old Ratan Kumar, overshadowed Kapoor in terms of popularity during this brief period. However, even Raj Kapoor did not stay in the shadows.

Even to this day, child beggars and young laborers flood the streets of Bombay, and they are the most devoted and impressionable consumers of Bombay cinema. In both films, this child-like feature was used to start creating the legend of Bollywood with the help of Bollywood itself. In "Do Bigha Zameen," the young comedian Jagdeep, who will enter the pantheon of great local film clowns and continue to entertain the audience until the 2000s, played the leader of street boys. In the middle of a workday, he would tell his friends about his encounter with "The Tramp" and boast to the younger boys that he saw the scene where Nargis undressed behind a curtain in front of Raj Kapoor: "Behind the curtain, she was completely naked... What a beauty!" Everyone was so excited by this scene that India's then-Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, gifted Jagdeep his own walking stick, without which he never appeared in public, and Soviet pioneers, clearly concerned about the same scene from "The Tramp," sent Jagdeep a red tie as a gift.

And in "Shoeshine" upon meeting the living Raj Kapoor on a train, the young heroine simply can't believe her eyes or her fingers when he lets her touch him to confirm that he's real.

Poster of the film "Do Bigha Zamin", 1953/Wikimedia Commons

And thus, Bollywood begins to create its own myth, while at the same time heading down a dangerous path that one of the fathers of neorealism, Luchino Visconti, also took in those very years: mourning and poeticizing the decline of the fading aristocratic and feudal tribes.