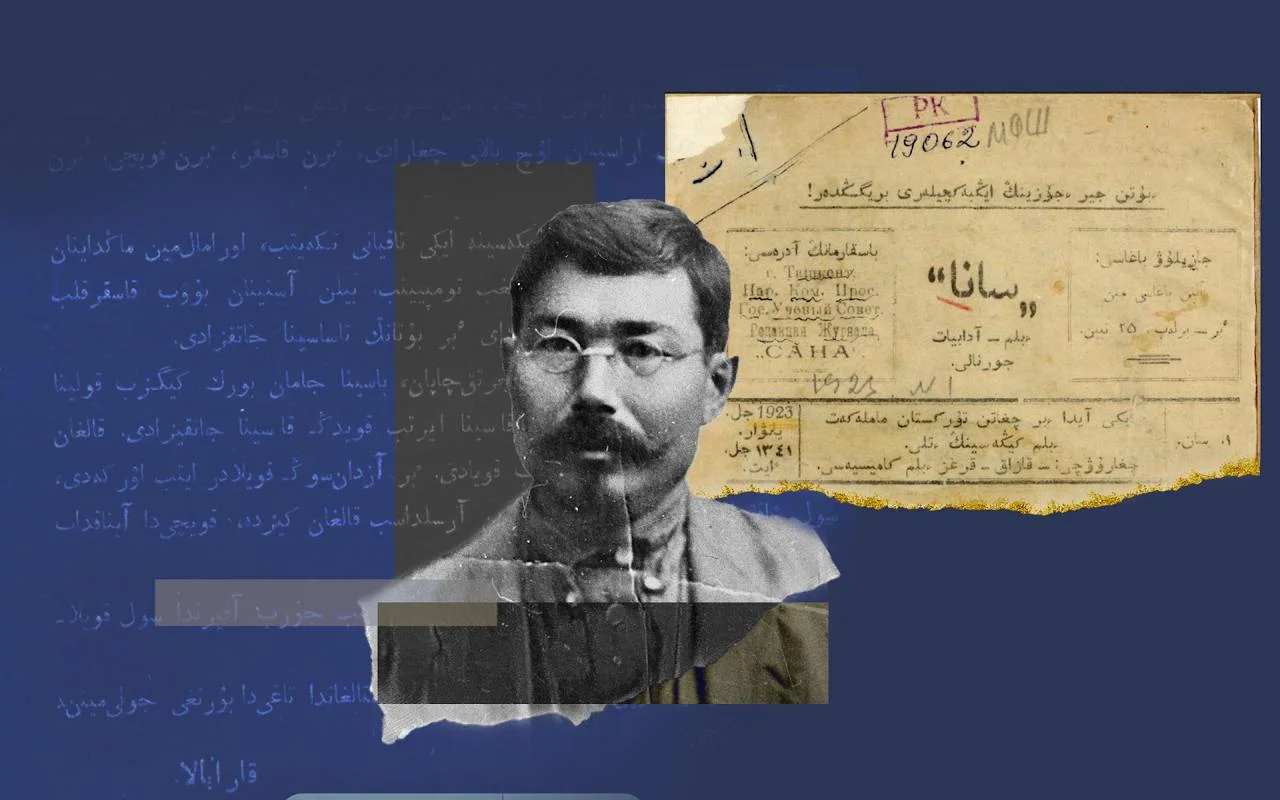

In 1930, Khalel Dosmukhamedov, a prominent Kazakh jurist and a key figure in the Alash Orda autonomy movement, was arrested along with other members of the Alash movement in what became known as the case of ‘the underground counterrevolutionary organization of citizens of Kazakh nationality’, one of many politically motivated purges of the time. The investigation lasted almost two years, and Dosmukhamedov was repeatedly interrogated, including about his role as editor of Sana, the first scientific and literary journal published in the Kazakh language in 1923. According to the investigation, it was during that same period that he was allegedly engaged in ‘counterrevolutionary activity’. Once celebrated as a scholar and nation-builder, Khalel Dosmukhamedov's life traces the rise, hope, and tragic downfall of Kazakhstan’s early intelligentsia.

- 1. The Famine and ‘Alash’

- 2. A Rebellious Young Man

- 3. From Physician to Educator

- 4. Participation in the Alash Movement

- 5. The First Scientific and Literary Journal in the Kazakh Language

- 6. ‘I Don’t Remember Whose Other Articles Were Included.’

- 7. Exile to Voronezh, Tuberculosis, and a New Arrest

- 8. A Letter from the Past

- 9.

The Famine and ‘Alash’

The year was 1930, and across the Kazakh SSR, the Soviet government’s sweeping policies of collectivization and livestock confiscation were being implemented with force. Soon, these measures, intended to transform traditional nomadic herding into collective farming, had become the leading causes of the mass famine, or the asharshylyq. The term asharshylyq is the Kazakh word for the devastating man-made famine that took place in Kazakhstan between 1930 and 1933. According to various estimates, approximately between 1.5 and 2 million people died from hunger, disease, displacement, and their consequences, which amounted to nearly half of the Kazakh population at the time.

When the authorities began the forced confiscation of livestock in favor of the state, the steppe dwellers naturally resisted, as these animals were not merely property. Families hid their herds in remote pastures and fled to neighboring countries. The national intelligentsia also largely opposed the collectivization program, voicing their dissent openly or in private conversations, aware that dissent could lead to imprisonment or worse.

Delegates of the 10th Congress of Soviets from Kazakhstan. 1st row: Kh. Dosmukhamedov (left), A. Orazbayeva (4th from left); 2nd row: A. Dosov (1st from left), S. Mendeshev (5th). Moscow, 1922 / Central State Archive of Film, Photo, and Sound Recordings of the Republic of Kazakhstan

At that time, thirty people were arrested under Case No. 2370, accused of belonging to the ‘underground counterrevolutionary organization of citizens of Kazakh nationality’. Among them were Mukhamedzhan Tynyshpaev, one of the leaders of the construction of the Turkestan-Siberian Railroad (Turksib); Alikhan Yermekov, the first Kazakh professor of mathematics; Mukhtar Auezov, who would later become a renowned writer and playwright; and Khalel Dosmukhamedov, who at the time of his arrest was serving as vice-rector of the Kazakh Pedagogical Institutei

These intellectuals were accused under multiple sections of Article 58, the infamous Soviet law used to silence political dissent. They were charged with 'sabotage' (Article 58.7) and 'participation in a counterrevolutionary organization' (Article 58.11), both of which carried severe penalties. Everything connected to their activities within the Alash party and Alash Orda during the early years following the Revolution was revived and used against them.

This is what Khalel Dosmukhamedov wrote from prison in one of his statements to the Collegium of the Joint State Political Directorate (abbreviated in Russian as OGPU), the Soviet Union's secret police agency from 1923 to 1934, after a year of investigation and interrogations:

While acknowledging my guilt in acting against Soviet power during the years 1922 to 1924, I do not wish to take upon myself guilt for the period from 1924 to 1930, for which I am not responsible. I would like to add that I have long since repented for my criminal activity against the Soviet government. I also wish to emphasize that this realization did not come to me here, in prison, but much earlier—I suffered deeply and repented. Furthermore, I must state that I never engaged in any organized agitation, much less in any measures to disrupt the procurement of grain or livestock. I once held a negative view of the collectivization of Kazakh households, but now I regard it favorably and consider it a necessary measure to end the half-starved existence of the Kazakh people. I acknowledge my errors.

A Rebellious Young Man

The story of young Khalel’s coming of age resembles the biographies of many representatives of the Kazakh intelligentsia of the early twentieth century. He was born at the end of 1883 in the Taisoigan area of the Ural region, which at that time was part of the Russian Empirei

On the morning of January 9 (at the Narva Gates). Engraving. 1925 / Wikimedia Commons

In 1894, at just eleven years of age, Khalel entered the preparatory course of the Military Real School in Uralsk. He completed the full course of study eight years later, graduating with distinction. Rather than immediately leaving for further studies, he chose to remain in Uralsk for an additional year to master Latin, which was a necessary requirement for entry into the prestigious Imperial Military Medical Academy in St. Petersburg. A year later, in 1903, Khalel successfully passed the Latin exam and was admitted to the academy in the capital.

Khalel’s student years, however, coincided with a turbulent period in the Russian Empire. In January 1905, troops opened fire on a peaceful workers’ demonstration in St. Petersburg, an event that came to be known as Bloody Sunday. This tragedy had far-reaching consequences: it not only shattered public faith in the tsarist regime but also became the catalyst for the revolutions of 1905–07.

Being at the epicenter of political upheaval inevitably influenced the formation of young Dosmukhamedov’s views. At the time, he wrote agitational and national-enlightenment articles for newspapers such as Uralsky Listok and Fikri

Kazakh students during the Russian Empire period. Khalel Dosmukhamedov — student of the Imperial Military Medical Academy in St. Petersburg (3rd row, 3rd from left); Mukhamedzhan Tynyshpaev — student of the Emperor Alexander I Institute of Railway Engineers (2nd row, 2nd from right). 1903–1909 / From the collections of the Museum of the History of Almaty

An archival document preserves a letter from twenty-one-year-old Khalel, intercepted by the Department for the Protection of Public Securityi

In his letter, Dosmukhamedov describes his ‘enchanting impressions’ from visiting his native auli

… these people are capable of labor and progress, and perhaps one day this country will take an honorable place among the nations of the world; perhaps it may even become a second Japan …”

He goes on to write about the oppression of the Kazakh people under colonial rule and what could—and should—be done to change it.

From Physician to Educator

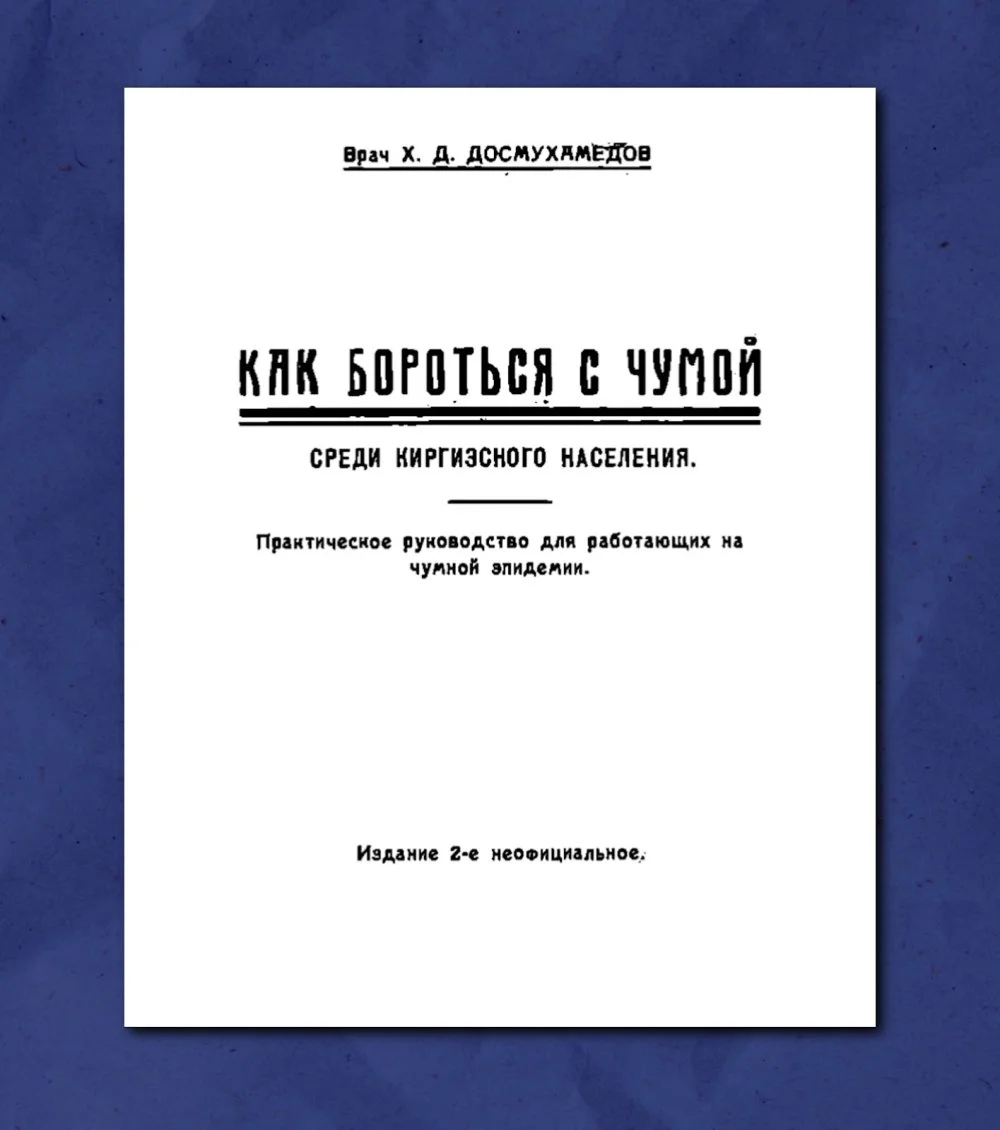

At the beginning of the twentieth century, epidemics of plague, typhus, and other bacterial infections were sweeping through much of the world. Penicillin, the first true antibiotic, would not be discovered until 1928, and it would take more than a decade—in the 1940s—for it to come into widespread medical use for treating infectious diseases. These conditions were just as relevant in the Kazakh steppe, and that is why, even while still a student at the Military Medical Academy, Khalel began to put his medical training into practice:

… his grandfather built a four-room house in Taisoigan, and when Khalel came home for holidays or later for celebrations, he would receive patients there and conduct medical examinations for all residents of the area, young and old alikei

After graduating from the academy in 1909 with honors in medicine, Dosmukhamedov was assigned as a medical officer, first to the Second Turkestan Battalion and later to the Second Ural Battalion. Four years later, he was discharged from military service and appointed as a district doctor in the Temir uezdi

At that time, medical care in Kazakhstan was extremely underdeveloped. There was a shortage of doctors and a lack of knowledge about basic sanitary and epidemiological principles. All of this contributed to outbreaks of plague among the Kazakhs in 1912–13 and again in 1915. As a physician, Dosmukhamedov took part in combating these epidemics but he understood at a deep level that treatment for these diseases alone was not enough—education was just as essential.

Therefore, in 1916, he published a brochure titled ‘How to Fight the Plague Among the Kirgiz Population’ (at the time, the Kazakhs were officially called Kirgizs), which contained a detailed description of all the sanitary and epidemiological measures he thought necessary. In 1924, his recommendations were published again in the form of a full-length book.

Kh. Dosmukhamedov. How to Fight the Plague Among the Kirgiz Population. 1924 / From open sources

At the same time, Dosmukhamedov continued writing for the Fikr and Uralsky Listok newspapers; only now his writing focussed on medical topics, including articles on infections and methods of prevention rather than political issues. When Akhmet Baitursynuly and Mijaqyp Dulatuly, influential early twentieth-century Kazakh intellectuals, educators, and leaders of the Alash movement, launched the Qazaq newspaper, he began to write for that publication as well. Through this work, he became closely acquainted with the future leaders of the Alash movement, a connection that would only deepen after the 1917 Revolution.

Participation in the Alash Movement

Popular science publications on medical topics were not the only expression of Dosmukhamedov’s civic engagement. He also took part in meetings and discussions about the future of the Kazakh people. Together with other like-minded individuals—many of whom had formed a core group after the 1905 Revolution—he became a member of the Alash party.

In December 1917, Dosmukhamedov was elected chairman of the Second All-Kazakh Congress in Orenburg. This was a historic event where the delegates voted to proclaim the autonomy of the Alash Orda. Dosmukhamedov voted in favor of the resolution, aligning himself with the movement for national self-determination. Later, the Soviet government would remember these events—though for a time it pretended to have forgiven them, as the country was in desperate need of qualified specialists like him.

Khalel Dosmukhamedov, member of the Alash-Orda government. 1917–1919 / From the collections of the Museum of the History of Almaty

In the spring of 1918, Khalel Dosmukhamedov, along with his namesake—though not a blood relative—Zhakhansha, traveled to Moscow for negotiations with Lenin and Stalin. Afterwards, both of them became co-leaders of the Provisional Kyrgyz Government of the Uil Region of the Alash Orda.

That same year, he was appointed as one of the four leaders of the Western Branch of the Alash Orda. But any hopes for genuine autonomy ended up being short-lived. By 1920, it had become clear that autonomy would not be realized. All existing autonomous governments were dissolved, and the remaining valuable specialists were reassigned to places where they were needed most. For example, Khalel Dosmukhamedov was appointed to several medical positions in Tashkent. A year later, he became the chairman of the Kazakh (Kyrgyz) Scientific Commission under the State Scientific Council of the People’s Commissariat of Education of the Turkestan Republic. This became a new chapter in his life, one that he would later be reminded of during future investigations.

The First Scientific and Literary Journal in the Kazakh Language

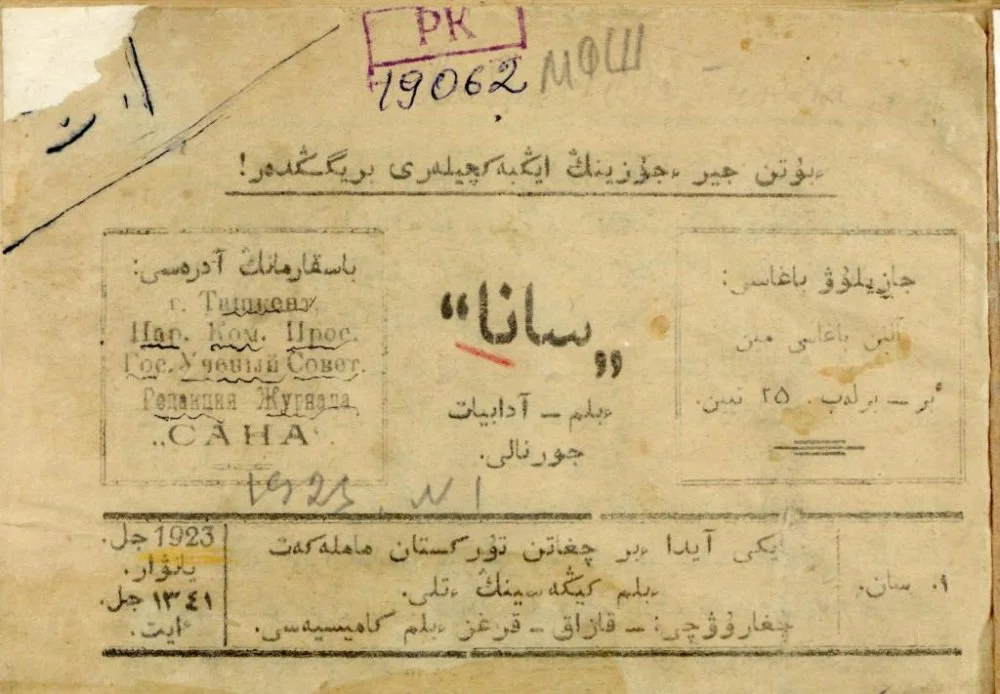

After Khalel Dosmukhamedov was appointed chairman of the Scientific Commission, he worked to convince the State Scientific Council of the importance of publishing an educational periodical not only in Russiani

In 1923, Sana (‘Consciousness’) in Kazakh and Bilim Ochyagy (‘The Hearth of Knowledge’) in Uzbek began to be published. They became the first illustrated educational magazines aimed at the peoples of the Turkestan Republic.

The magazine Sana was, in essence, the first popular science publication in the Kazakh language and the culmination of Khalel Dosmukhamedov’s twenty years of educational work. It is no surprise that he became the editor of this publication. In the first issue of Sana, published in January 1923, he wrote:

Our time is an age of culture, and knowledge is the path to it. Acquiring knowledge is not easy; it requires hard work and great patience … Our goal in creating Sana is to fill in the gaps as much as possible and provide teachers and the younger generation of students with clear explanations. It is challenging work, but work that must be undertaken.

This issue featured popular science articles, literary and artistic news, research papers, zhyr (narrative or declamatory songs), poetry, and historical-ethnographic notes on the traditional children’s games of the steppe peoples.

The original plans for the magazine Sana were as follows: a print run of 2,000 copies, eight printed sheets per issue, and four issues per year. In the end, however, only two issues were published.

Cover of the first issue of the magazine Sana / National Library of the Republic of Kazakhstan

Khalel Dosmukhamedov was not only the editor of the magazine but also one of the main contributors to the magazine. Among the other contributors were at least twenty individuals, many of whom were well-known figures, including: Sanjar Asfendiyarov, who at the time was serving as People’s Commissar of Health of the Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR); Mukhtar Auezov, the future writer and playwright; Mukhamedzhan Tynyshpaev, then head of the Water Management Department of the Turkestan Regional People’s Commissariat for Land in Tashkent; Oraz Zhandosov, who was then still a student; Magzhan Zhumabayev, who was a poet, publicist, and educator; Akkagaz Doszhanova, one of the first female Kazakh doctors; Turar Ryskulov, who at that time was chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars (CPC) of the Turkestan ASSR; and the namesake of the editor-in-chief, the lawyer Zhakhansha Dosmukhamedov.

Many contributors wrote under pseudonyms, a common practice at the time to avoid unwanted attention from the authorities. This precaution proved crucial because eight years later, when he was being interrogated, Khalel Dosmukhamedov was able to protect his colleagues by keeping their real identities undisclosed.

‘I Don’t Remember Whose Other Articles Were Included.’

After their arrest in 1930, each of the suspects in Case No. 2370 (‘The underground counterrevolutionary organization of citizens of Kazakh nationality’) repeatedly gave testimony under pressure, explaining or justifying their actions from previous years. A separate interrogation on 4 May 1931 was ‘dedicated’ to the creation and operation of the journal Sana. And this is what Khalel Dosmukhamedov said in his testimony to the Joint State Political Directorate (abbreviated as OGPU) investigator:

… I was appointed editor of the journal Sana by the People’s Commissariat of Education. At that time, there was a severe shortage of skilled writers, making the continuous publication of the journal difficult, so publication stopped after the second issue. As far as I remember, these two issues included articles by myself, Divaev, and Zhumabayuly. I do not remember whose other articles were included, nor do I know whether there were any articles by Iskakov. At that time, there were very few writers among the communists, and those who existed held high positions and generally did not have time for the journal. In my opinion, none of their articles were included.

The articles published in the journal were reviewed and analyzed by the Kazakh-Kyrgyz Education Commission; in particular, articles of a pedagogical nature were selected by the Scientific and Pedagogical Commission, headed by its chairman, Arkhangelsky. There was nothing in the journal’s articles that promoted nationalism.

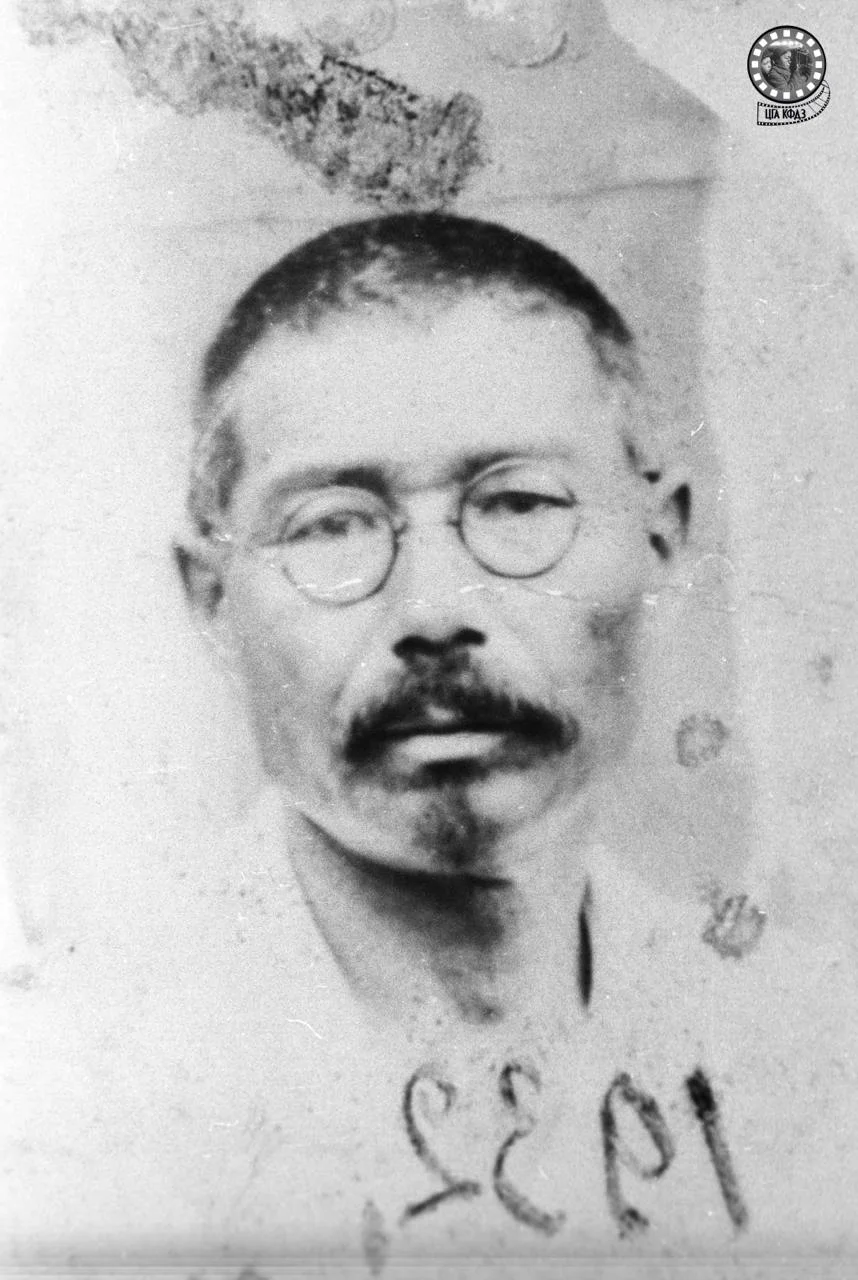

From 1922 to 1924, Khalel Dosmukhamedov, like many representatives of the Kazakh intelligentsia and former members of Alash Orda, lived and worked in Tashkent. According to the testimony of some of the defendants in Case No.

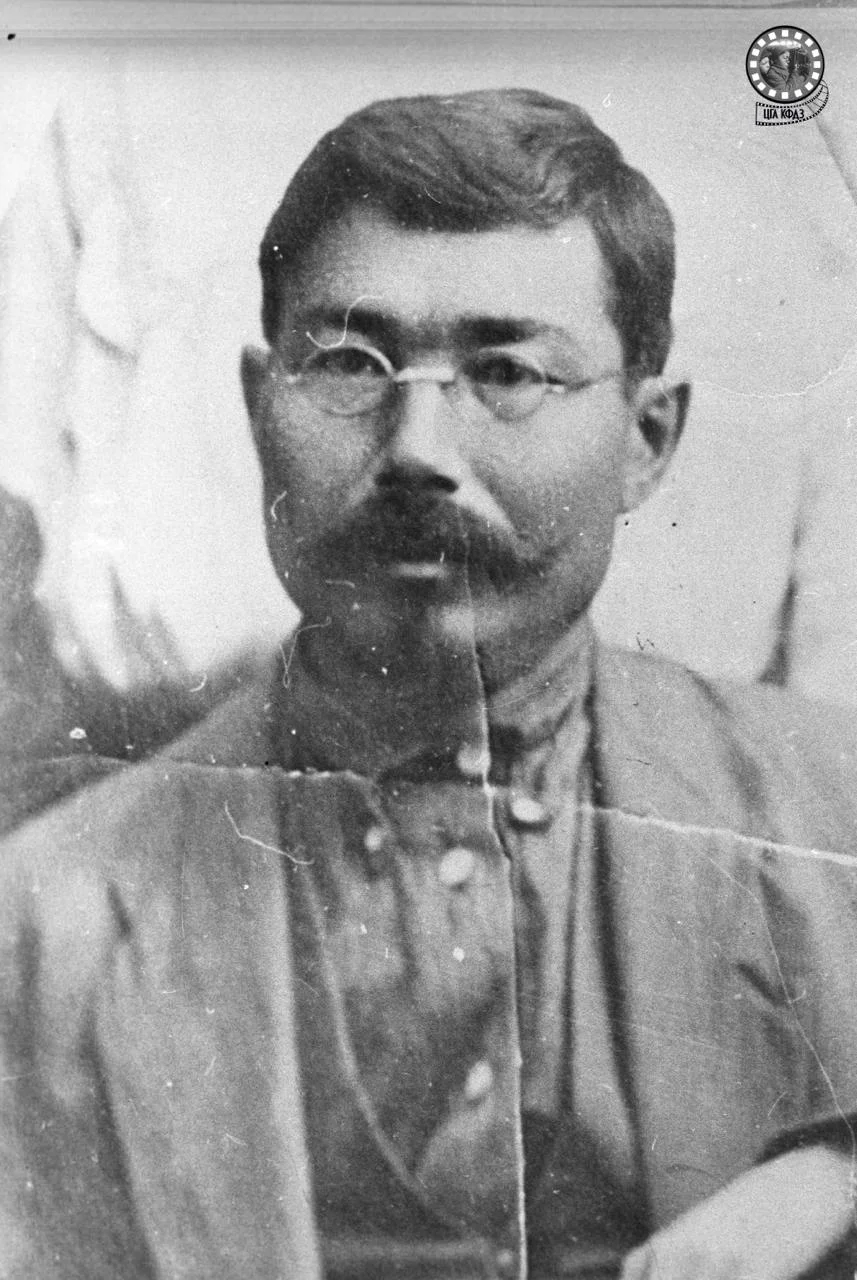

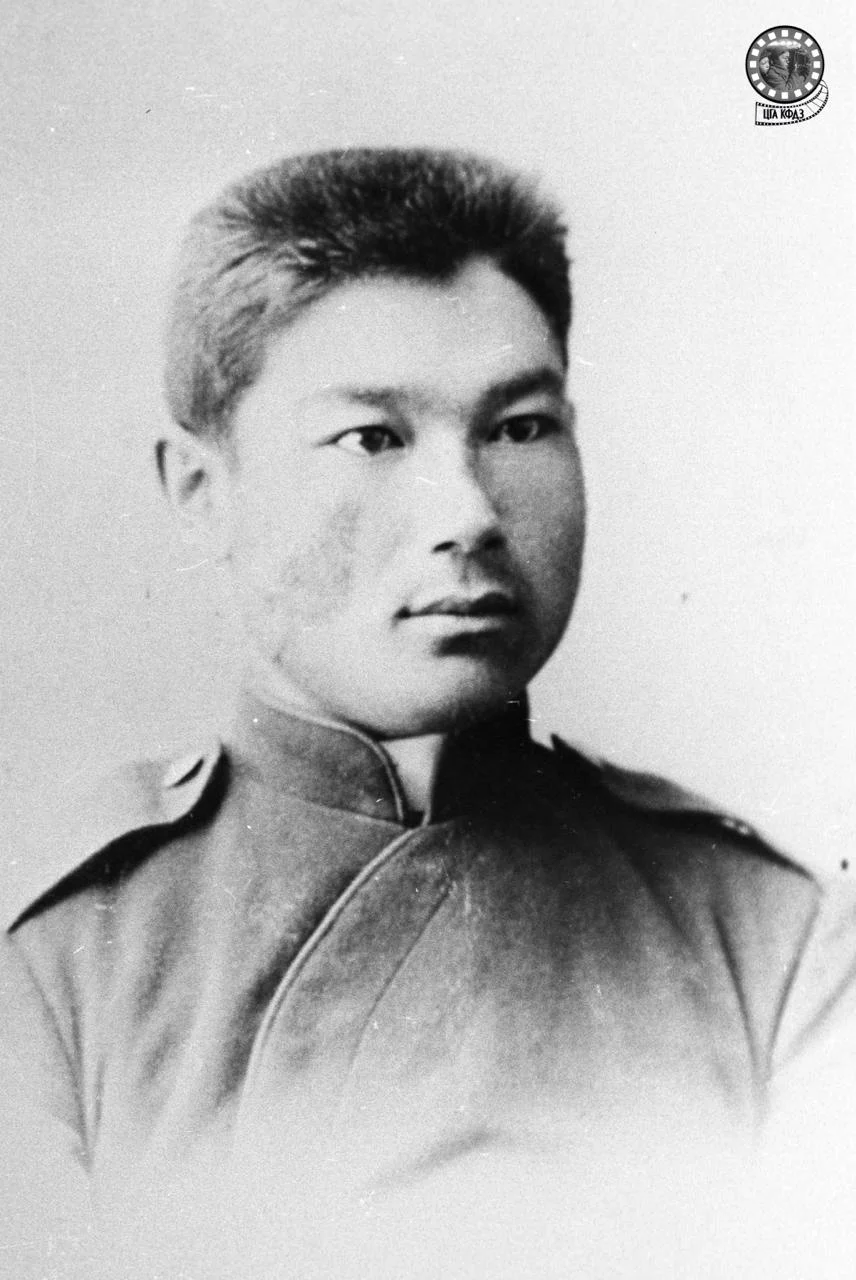

Khalel Dosmukhamedov. 1929 / From the collections of the Atyrau Regional Museum of History and Local Lore

2370, during that period, he would gather them in his home. One of the main topics of discussion was the revival of Alash activities. In his later statements, Dosmukhamedov admitted to some of the charges, while denying others:

On October 25 of this year, I was charged under Article 58.7, 10, and 11, and Article 59.3, for various crimes against the Soviet government. Of these charges, I admit guilt in the following:

-

In 1922, I participated in organizing a clandestine circle that included elements of anti-Soviet activity in its program and work.

-

In the same year, 1922, I met with Zaki Validov, who had come to Tashkent under amnesty, and had a conversation with him.

-

Until mid-1924, I promoted national bourgeois-democratic ideology among my students.

In all other alleged crimes, I consider myself innocent. After 1924, I did not participate in any anti-Soviet organizations, circles, etc., and was not involved in any anti-Soviet work.

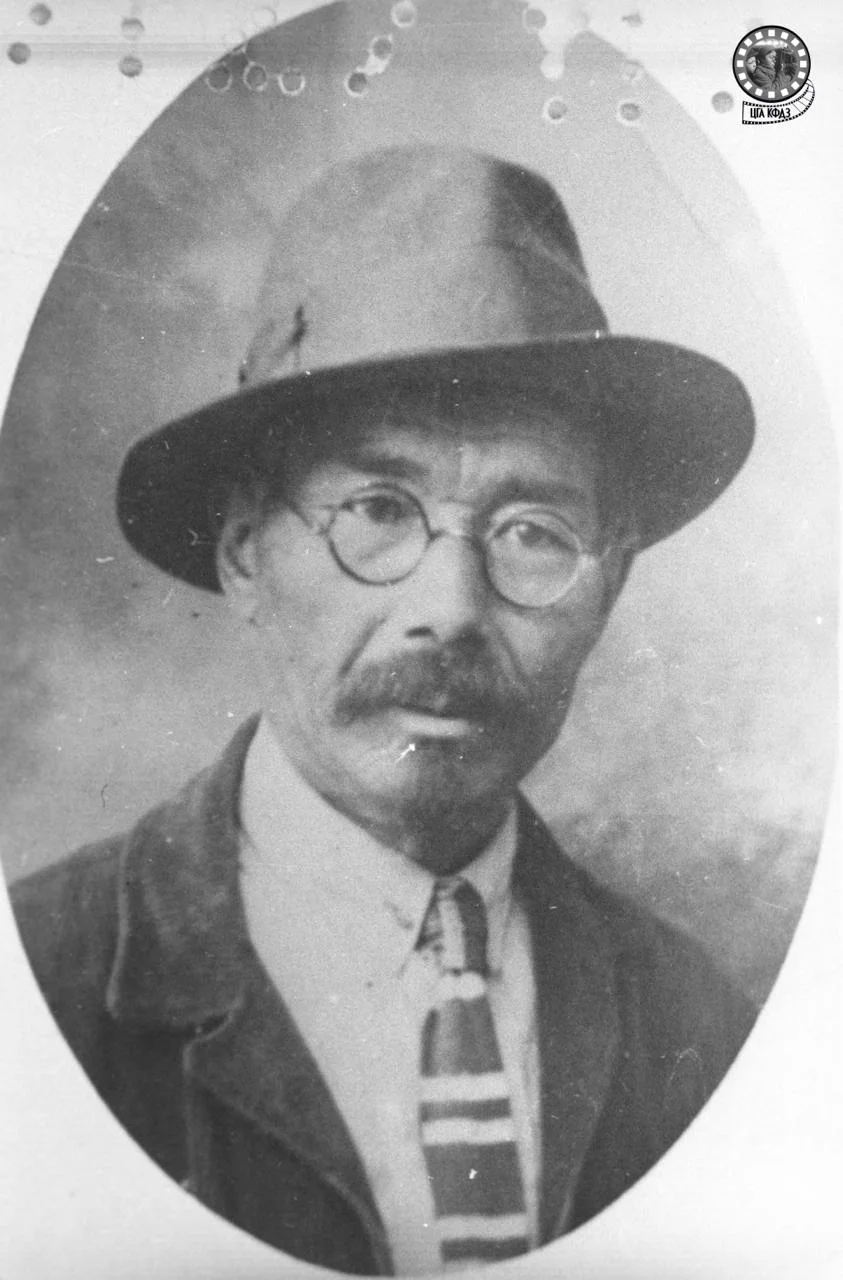

Exile to Voronezh, Tuberculosis, and a New Arrest

In April 1932, Khalel Dosmukhamedov, along with other members of the Alash Orda, was sentenced by the court to five years in a labor camp, with the sentence later converted to a longer term at a partial restriction location, abbreviated as PChOi

Khalel Dosmukhamedov during exile. Voronezh, 1932 / Central State Archive of Film, Photo, and Sound Recordings of the Republic of Kazakhstan

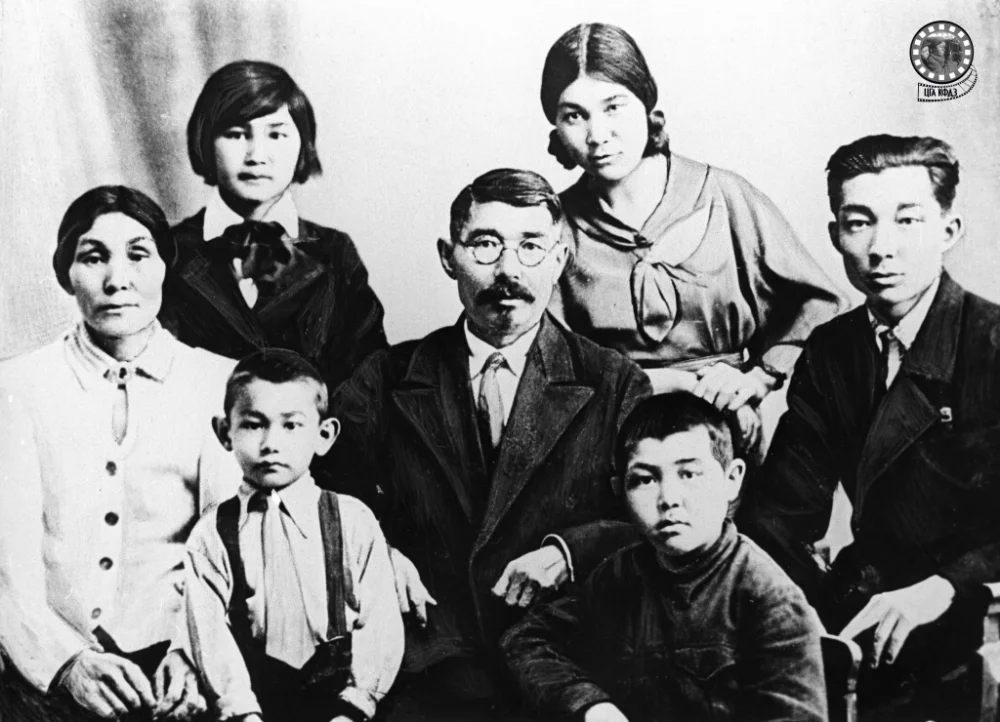

After the sentence, Dosmukhamedov, along with his family, was exiled to Voronezh in southwestern Russia. In 1933, he contracted severe pulmonary tuberculosis, but despite his illness, he remained the sole breadwinner of the family. Two of his children also suffered from tuberculosis and tuberculin intoxication.

Hoping for mercy, Dosmukhamedov petitioned the OGPU Collegium of the USSR for release or at least mitigation of his sentence. In a letter to them, he wrote:

Due to my illness, all members of my family are at risk of contracting pulmonary tuberculosis, as in my current condition, I am unable to create conditions to prevent disease in the family. My illness frequently worsens and progresses rapidly. Treatment for the lungs under local PCHO conditions will be ineffective. It is an unattainable goal for me …

His sentence was not reduced; in fact, even after doctors had confirmed his diagnosis, Khalel Dosmukhamedov was still required to continue working within Voronezh’s healthcare system.

Khalel Dosmukhamedov with his wife and children. 1930 / Museum of the History of Almaty

In 1938, during a new wave of repressions, Khalel was arrested once again under Article 58 of the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic (RSFSR) Criminal Code, and one year later, he was sentenced to execution. However, he did not live to see the sentence carried out—the former editor of the first Kazakh popular science magazine, Sana, died of tuberculosis in a prison hospital in Almaty.

Twenty years later, in February 1958, the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR overturned the verdict of the military tribunal of the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs’ (abbreviated as NKVD) troops of the Kazakh SSR regarding Khalel Dosmukhamedov. The case was dismissed for lack of a crime, and a certificate of rehabilitation was sent to his wife Katira Dosmukhamedova.

Khalel Dosmukhamedov. Voronezh, 1932–1938 / From the collections of the Museum of the History of Almaty

In the fifty-six years of his life, Khalel Dosmukhamedov not only actively participated in profound historical events and the lives of his people, but also made significant contributions as a physician, author of popular science works, and educator. In addition, he studied the history of Isatay Taimanov’s popular uprising. He was a literary scholar and ethnographer, comparing folklore traditions with historical and ethnographic data. His main achievement in this field was the essay ‘Literature of the Kazakh People’, which was published in 1928.

He also authored the first textbooks on natural sciences in his native language and ‘… provided the first 466 equivalents of anatomical terms in Kazakh’i

A Letter from the Past

In a 1904 letter to his friend Gubaidolla Berdiyev, which was intercepted by the Department for the Protection of Public Security, Khalel Dosmukhamedov wrote lines full of reflection on the events around him:

It is frustrating that, seeing all this, you can do nothing yourself. We all idealize that we will help the people, but when? Yes, brother, all of this weighs heavily on the heart. Only you will understand me and sympathize …

Khalel Dosmukhamedov — student of the Ural Military Real School. Uralsk, 1895–1902 / Central State Archive of Film, Photo, and Sound Recordings of the Republic of Kazakhstan