In the late spring of 1560, a small ship berthed in the Port of London, having set sail several months previously from the White Sea in the far north of Russia. On board was a young woman from Central Asia named Aru Sultan. We know little about her background besides the fact that the great Elizabethan merchant-adventurer Anthony Jenkinson had first made contact with her on his ground-breaking journey from northern Russia to Moscow and then down the great Volga River past Kazan and Astrakhan, from where he had taken a ship to the east coast of the Caspian Sea before reaching the legendary city of Bukhara.

An Enigmatic Arrival

Today, Aru Sultan—more commonly known in the English-speaking world as Aura Soltana—remains an enigma, though new information continues to emerge. We know that soon after her arrival in London she became a lady-in-waiting to Queen Elizabeth I1

Elizabeth Bassett, Countess of Newcastle, c1615. Artist: William Larkin. - Image ID: MPWCXW

Some fashion historians, while noting the impact she had on court dress, believe she was merely a slave girl, picked up by Jenkinson2

George Gower: Queen Elizabeth I. c. 1567, private collection/Wikimedia Commons

The Adventurous Merchant: Anthony Jenkinson’s Expeditions to the East

Jenkinson himself was born into a wealthy Leicestershire family in 1529 and by the time he left on the first of his three Caspian expeditions was already an accomplished sailor and adventurer. By the age of 17 he had travelled extensively as a textile merchant throughout Europe, Ottoman Empire, the Levant and many Mediterranean islands. He had also visited the North African coast and sailed north from England to the Arctic seas.

He was just 30 when he set off from Greenwich on 12 May 1557 on his first Central Asian journey in a flotilla of four ships bound for Russia. His aim was to obtain a safe-conduct from the Russian Tsar, Ivan IV (‘the Terrible’), which would allow him to reach the Caspian and from there travel on to India and possibly to China to open up new trade routes.

Alexander Litovchenko: Ivan the Terrible Showing Treasures to the English Ambassador Jerome Horsey. 1875/Russian Museum

You may wonder why English merchants at this time were willing to travel to such remote places in order to sell their goods – mainly English worsted cloth. This was because England was being shut out of Europe by the Catholic powers, and Elizabeth herself was threatened with excommunication – which eventually happened in 1570 – for her refusal to acknowledge the primacy of Rome in religious affairs. English merchants were desperate to find new markets and the Silk Route trade with India and China offered some kind of alternative. To overcome these obstacles, in 1580, Elizabeth would even agree a trade treaty with the Ottoman Empire that would last for the next 343 years.

Jenkinson’s ships arrived in northern Russia on 12 July 1567 where he and his party disembarked and headed for Moscow 500 miles to the south. It would be another nine months before Jenkinson set out towards ‘Cathay’ (China). During his stay in Moscow he met several times with Tsar Ivan IV who gave him the documents he needed. According to some sources, he may even have been an intermediary in Ivan’s efforts to persuade Queen Elizabeth I to marry him.

In April 1558, together with brothers Richard and Robert Johnson and a Tartar interpreter, Jenkinson set off for the south. These were troubled times; only a year previously Ivan’s troops had finally broken the grip of the Golden Horde on Russia, overrunning the Kazan Khanate and laying waste to the land. Thousands of unburied bodies still lay in the streets when Jenkinson passed through, although Russian reconstruction had started.

Kazan in the engraving by Adam Olearius. 1630 / Wikimedia Commons

By the time Jenkinson reached Astrakhan, at the mouth of the Volga, that city too was in a terrible mess. The Russian invasion had been followed by plague and famine. Many local Nogais (or Nogai Tatars, how he calls them) were being offered as slaves. As Jenkinson himself noted:

“At my being there I could have bought many goodly Tartar children…to say, a boy or wenchi

The likelihood is that Jenkinson came across Aru Sultan on his journey south down the Volga. We don’t know the precise circumstances of the meeting, but rather than take her with him further into Central Asia, he decided to send her back north, to be placed into the care of Henry Lane, master of the Muscovy Company, who was resident at the Company’s headquarters at Vologda, 300 miles north of Moscow on the route towards the White Sea. In a letter written to Lane from Moscow on 18 September 1559 after returning from Central Asia, Jenkinson gives ‘most heartie thanks’ to his boss ‘for my wench Aura Soltana’i

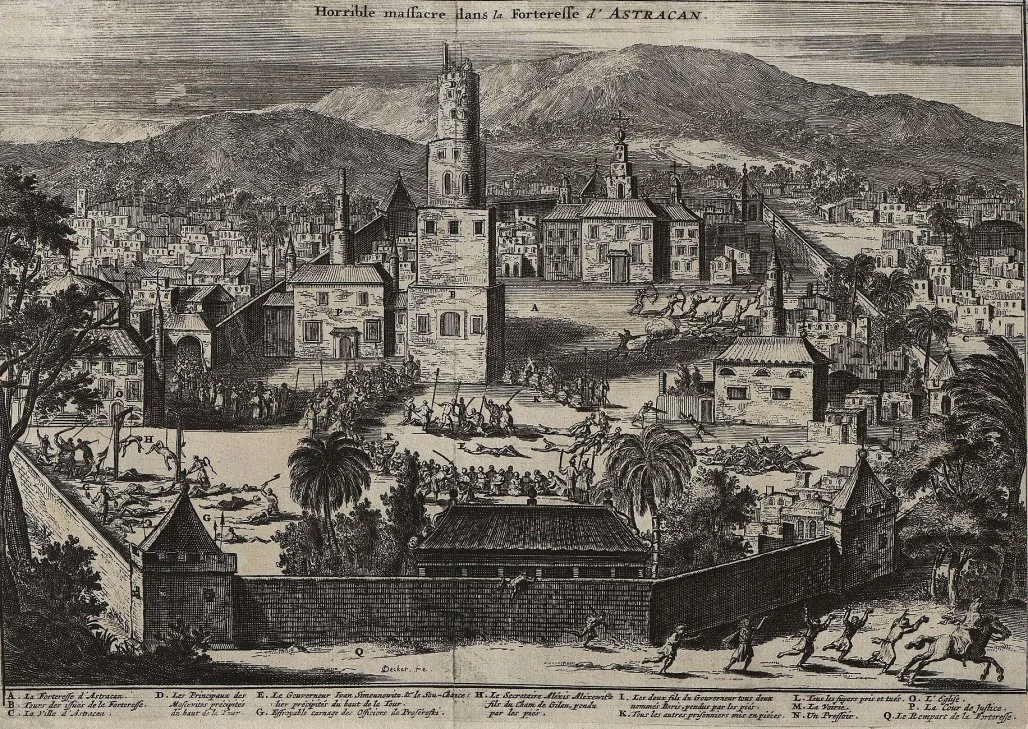

Russia. Astrakhan. The capture of Astrakhan by the rebellious peasants of Stepan Razin in 1670 ("The terrible massacre in the Astrakhan fortress"). Engraving of 1719/Wikimedia Commons

The idea that she was a slave seems to have arisen from Jenkinson’s comments about their cheapness in Astrakhan. This is even though in the very next sentence he makes the point that he had no need to buy slaves and that purchasing victuals was far more important. The fact that Jenkinson paid for the release of 25 captured Russian slaves in Bukhara and brought them back to Moscow with him may suggest he was not a supporter of the slave trade.

From Astrakhan onwards Jenkinson was outside the territory of the Russian Tsar. Together with a group of Tartar and Persian merchants he left the city on 6 August 1558, mapping the coastline as he sailed. Almost a month later they reached the port of Mangishlaki

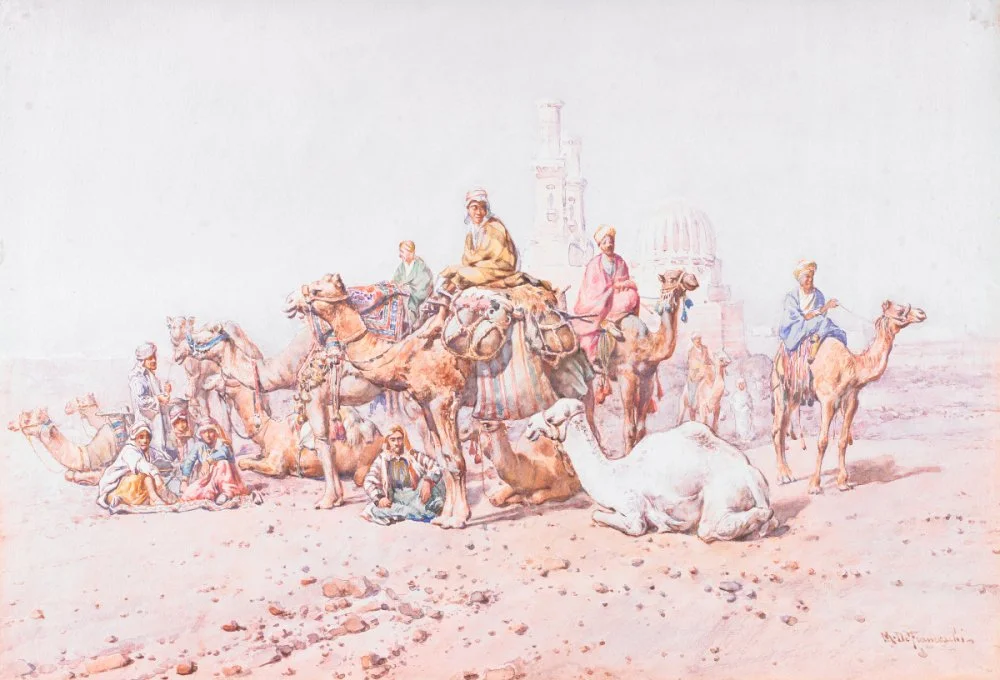

Camel Caravan at Rest by Mariano de Franceschi. late 1800s/Birmingham Museum of Art/Wikimedia Commons

Jenkinson arrived in Bukhara on 23 December, staying until 8 March 1559. Wars and uncertainty prevented him carrying on his journey towards India and so once he had disposed of his trade goods, he set off back to Moscow, where after an absence of a year and five months he arrived on 2 September 1559. As well as the freed slaves, he brought with him representatives of the khanates of Central Asia who were seeking audiences with the Tsar. In February 1560 he left Moscow and was back in London by June the same year.

S.M. Prokudin-Gorsky. Entrance to the Emir’s Palace in Old Bukhara. 1907 / Library of Congress

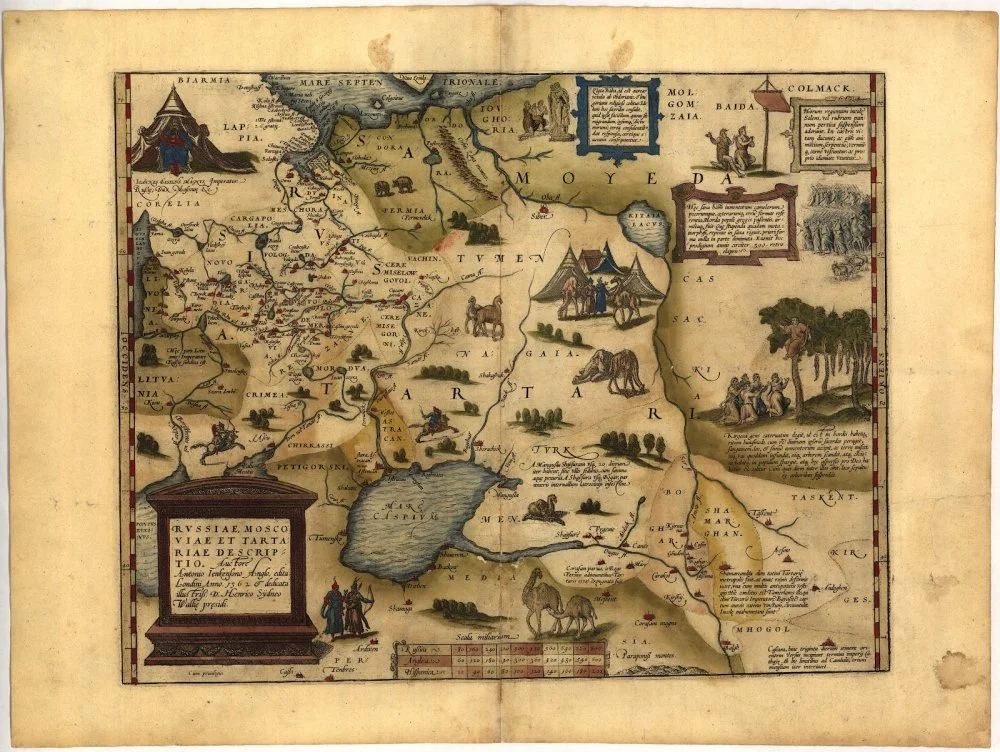

Almost immediately on his return Jenkinson started work on his map, together with mapmaker Nicholas Reynolds and editor Clement Adams. The detailed map, now acknowledged to be one of the earliest and finest ever produced of Central Asia, was published in a small edition of just 25 and then reprinted in a simplified form in Antwerp in 1562 by Ortelius, by which time Jenkinson had already left England on the second of his three Central Asian journeys.

Ortelius' map based on Jenkinson's map. Late 16th century/Library of Congress/Library of Congress

Until recently Jenkinson’s original map was only known from Ortelius’ simplified version. Even so, it is a ground-breaking map and the first to mention the Kazakhs by name. Their territory, to the east of the Caspian, is marked as ‘Kassackia’. No original copies of Jenkinson’s map were believed to exist, until a single copy was discovered in the Polish city of Wroclaw in 1987.

Anthony Jenkinson’s original map . 1562/Wikimedia Commons

A Fashion Icon at the Elizabethan Court

But let us return to the young ‘Tartar girl’, Aru Sultan. Historian Jessica Brain is amongst those who argue that she was bought as a slave during Jenkinson’s second journey to Central Asia. She adds that Aru Sultan was one of the first recorded Muslim women to arrive in England and that she was presented as a gift to Queen Elizabeth whereupon she soon became a significant member of the Royal Court, receiving many luxurious gifts, particularly textiles, directly from the Queen.

Robert Peake. A Procession of Queen Elizabeth.1600/Alamy

Professor Jerry Brotton, in his book The Sultan and the Queen, about Queen Elizabeth I’s relations with the Islamic world, notes that after Aru Sultan became a lady-in-waiting to Elizabeth she became a kind of fashion adviser, introducing new designs for shoes and court dress.

The first mention we get of Aru Sultan in London is in May 1560 when court rolls record that Elizabeth gave her some fine textiles, including two loose dresses of black taffeta, a French petticoat of russet satin and another French petticoat of black satin. These would have been clothes from the Queen’s personal wardrobe. This was the time when Queen Elizabeth also formed a close relationship with Safiye Sultan, principal consort of the Ottoman Emperor Murad III, to whom she sent many presents.

A portrait of Elizabeth Howard, Lady Southwell (c.1564 – 1646), an English Elizabethan lady wearing a farthingale dress with its distinctive protruding waist created by a padded roll and inserted wooden hoops. By an unknown artist c. 1600 CE/Wikimedia Commons

At around this time the young woman, thought to have been around 20 when she arrived, was given the added ‘nickname’ of Ippolyta the Tartarian. At court she was usually referred to as Aru Sultana Hippolyta. In Greek mythology Ippolyta was the Amazon (i.e. Central Asian) queen who married Theseus of Athens.

Hippolyta on a Late Antique mosaic. 5th–6th centuries CE / Wikimedia Commons

Note that these first gifts were bestowed by Elizabeth on Aru Sultan very soon after she had arrived in England, even before Jenkinson himself had returned. If she was a slave girl, how could she have risen so quickly to the point where the Queen was giving her valuable gifts? What is more, a year after this first recorded gift, on 13 July 1561, Elizabeth took part in what has been described as a symbolic baptism ceremony for Aru Sultan, through which the Queen became her godmother. The gifts presented to the young woman included more than 6 ounces of gold jewellery:

“Item, given by her Majestie, the 13th of July, anno predicto, to the chrystenyng of Ipolitan the Tartarian, oone chaine of gold, per oz. 4 1/2 oz. and two peny weights; and also oone tablett of gold, per oz. 1 ¾ dim. oz. Bought of the Goldsmith. In toto, 6 ¼ dim.oz. 2 dwts. gold.”

Not long after, Elizabeth I refers to Aru Sultan as ‘our deare and welbeloved woman Ipolita the Tartarian’. In 1562 she received a pewter doll from the Queen. In June 1564 the court rolls record her as receiving the following valuable textiles from the Queeni

-

A gown and kirtle of grosgrain chamlet edged with velvet

-

A gown of cloth; a kirtle of grosgrain

-

A petticoat of red cloth or grosgrain

-

A farthingdale of mockado

-

6 canvas smocks with Holland linen sleeves; 6 kerchiefs; 6 partlets with bands and ruffs; 4 pairs of Holland linen sleeves

-

Half a pound of "systers" thread for making the smocks and kerchiefs

-

6 ounces of Granada silk thread to embroider the partlets and sleeves

-

5 ounces of Venice gold thread for other embroidery

-

A "clout" of Spanish needles. The "clout" was a cloth to which needles were pinned.

-

A scarf of sarcenet

-

A velvet hat

-

2 cauls of gold, silver, and silk, costing £4.

Fashion historians, including Janet Arnold and Patricia Lennox, have noted the gifts of textiles to Aru Sultan and argued that she revolutionized fashion at the court of the Queen. Several pairs of leather shoes were made for her by the Queen’s shoemaker Garret Johnson, including shoes with heels made of Spanish leather, leather pantobles (slippers-ed) and velvet shoes. Arnold has suggested that the Queen copied this style from Aru Sultan. Until then, satin shoes had been the court fashion, whereas leather riding boots with heels were common on the steppe. The large number of gifts from the Queen in 1564, including livery clothes, shows that Aru Sultan remained in the Queen’s favour for some years as a lady-in-waiting.

Possibly the last reference to Aru Sultan – an order for the skinner Adam Bland to provide rabbit fur for her damask cloak - can be found in a court document from 1569.

Nicholas Hilliard. Elizabeth I in Satin Shoes. 1599 / Walker Art Gallery/Wikimedia Commons

But mysteries remain. Did she ever return home? If she stayed in London, did she marry and have a family? Did she die in England and if so where is she buried? Answers to some of these questions may lie in as-yet-undiscovered Royal court documents.

Damask cloak. 1866/ Alamy

A Contested Identity: Slave, Noblewoman, or Diplomatic Envoy?

There is also an alternative theory about both the role and the identity of Aru Sultan, now being put forward by the Kazakh historian Mukhit-Ardager Sydyknazarov, who argues that Aru Sultan was the first diplomatic representative of the Kazakh khanate and the first representative of the Islamic and Turkic world to arrive at the Tudor court of Queen Elizabeth Ii

Sydyknazarov goes on to argue that Jenkinson’s map, so much more detailed than that produced by Ortelius, could not have been created without information from someone well informed about society and politics in Central Asia. The informant, he suggests, was Aru Sultan herself. He points out that her name is clearly Kazakh, ‘Aru’ meaning beauty or beautiful girl and ‘Sultan’ indicating her class origin from the Kazakh nobility. Sultan was a title used for both men and women, usually given to the Chingisids – direct descendants of Chinggis Khan - who acquired it by birthright. In the sixteenth century royal burial vault in Turkestan in southern Kazakhstan can be found many women with the title Sultan as part of their name.

Jenkinson’s original map, says Sydyknazarov, includes 15 images of Kazakh women, a fact which is highly unusual in European cartography. “We assume that she helped Jenkinson to depict her mother with younger and older children, brothers and sisters, father, grandparents in various images on the map”, he says. He adds that their absence in Ortelius’ Antwerp version of the map is a result of Catholic intolerance

According to Sydyknazarov, there is little chance that Jenkinson could have travelled to Bukhara without the goodwill and knowledge of Khaknazar Khan, who was titular ruler of most of the territory through which he passed. The absence of documentary proof for a meeting between the two men is not necessarily proof of absence of such documentation, and it is only a matter of time, according to Sydnyknazarov before such documentation is found in an archive. He says that Jenkinson would not have broadcast his negotiations with the Kazakhs, as this may well have upset Ivan IV. Jenkinson would have been aware that opening up trade routes to India, for example, would have required the permission of the Kazakhs. This is why Aru Sultan was sent to London, so that these trade negotiations could be continued, he says.

Aru Sultan’s pedigree is unknown at present. She does not appear in Haqnazar’s family tree, although other siblings of the khan are mentioned, including his brothers Mamash and Abulkhair-Sultan and his sisters Mungatai Sultan, Din-Muhamed Sultan and Bozgyl Sultan.

As for whether or not she was a slave, Sydnyknazarov argues that it would have been impossible for Jenkinson to take a young female Muslim slave back to England. He simply would not have been allowed to do so. Nor would she have been allowed into the Royal Court in England and adopted as a lady-in-waiting unless she herself was of noble status.

A Portrait, a Mystery, and a Legacy

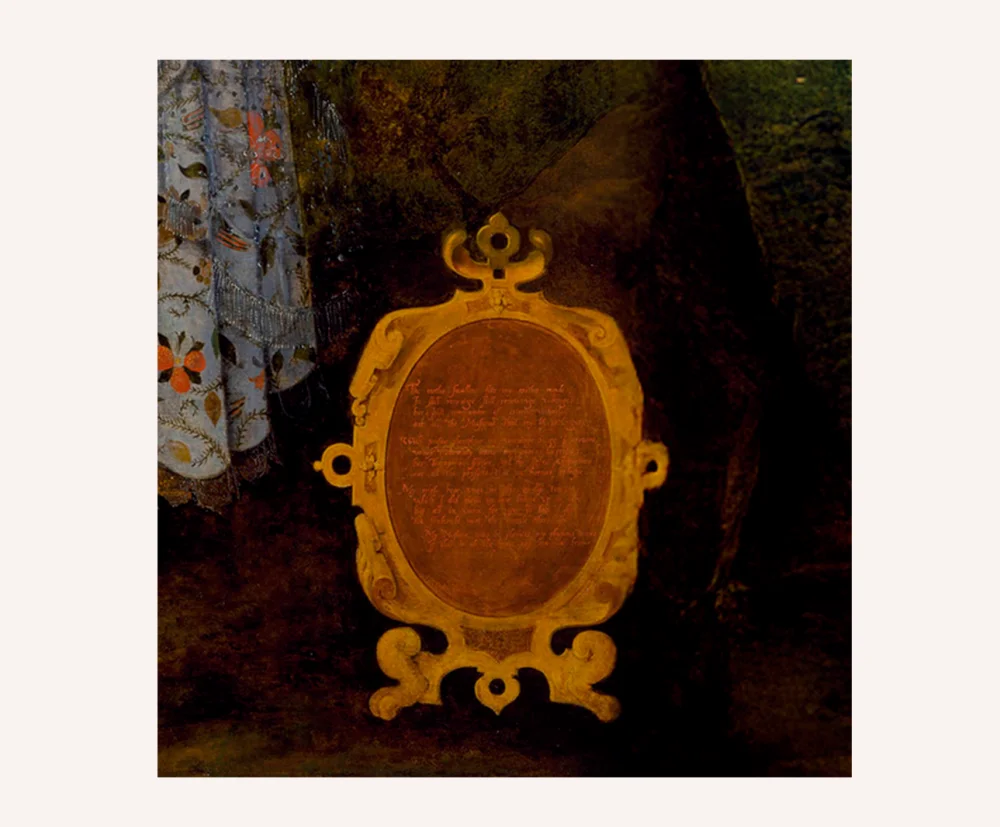

There is one remaining mystery connected to Aru Sultan. An untitled picture, painted by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (c1561-1636) and now hanging in Hampton Court Palace, has been identified by several historians as portraying Aru Sultan. The large portrait* [216x135cm], once thought to be of Queen Elizabeth herself, shows a woman wearing what is clearly a Central Asian costume. Indeed, the painting was also once known as ‘Lady in Fancy Dress’. In her hands she holds both a small crucifix and a set of Islamic prayer beads.

Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger. Detail of a painting. Rosary. Portrait of an Unknown Woman associated with Aura Soltana, 1590s/ Royal Collection, London/Wikimedia Commons

The subject of the painting appears to be a woman in middle age, fair-skinned and perhaps somewhat melancholic. She stands beneath a tree and is caressing the head of a deer with one hand. The gown (chapan) she is wearing is clearly not typically Elizabethan, with its low neckline and wrap-over fastening. More typical would have been a square-cut neck, with a high ruff. The patterns also suggest a Central Asian connection.

But most diagnostic of all is the hat the woman is wearing, which is very close in appearance to the tall saukele hats that were typical of Kazakhs and other Central Asians at the time. I found a very similar example in the National Museum in Almaty recently, identified as originating in Western Kazakhstan, close to the Caspian.

Jules de Cuvellier (1865–1927). Young Kazakh Bride, 1895 / gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

However, there are some problems with identifying this portrait as being of Aru Sultan. The artist, Gheeraerts, was born in 1561, the year after Aru Sultan arrived in London. Although undated, the picture is thought to have been painted around 1590, by which time she would have been around 50. However, no references to her have been found after the 1570s, which is when she is assumed to have died. Would Gheeraerts have painted her a dozen or more years after she died? And if she survived until the 1590s why are there no records?

The painting also includes a number of inscriptions and a long poem in a cartouche, typical of paintings of Gheeraerts. One inscription states (in Latin) ‘A just complaint of injustice’ and another by the stag’s head reads ‘Grief is medicine for grief’.

The inscriptions and the sonnet suggest a very sad figure who has been cheated in some way, perhaps in love. They are hardly the thoughts, we would assume, of someone who was god-daughter to the Queen and a recipient of many Royal favours. Nor do they square with the idea that Aru Sultan, if it is she, was a high-flying and important diplomatic figure. We must therefore be cautious in attributing the identity of the subject of this painting.

Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger. Cartouche. Detail of a painting. Portrait of an Unknown Woman associated with Aura Soltana, 1590s/ Royal Collection, London/Wikimedia Commons

In summary, it seems unlikely that Aru Sultan was ever purchased as a slave by Anthony Jenkinson. Her rapid adoption by the Elizabethan court soon after she arrived in England is not consistent with her being a slave girl. The close interest that Queen Elizabeth paid to her, donating valuable clothing and other gifts, including gold jewellery, becoming her godmother and allowing her to become a lady-in-waiting suggest that Aru Sultan had a pre-existing important status. Nor does it seem likely that Jenkinson would have been allowed by local khans in Central Asia to take a young Muslim woman back to England as a slave.

So even if it is likely she was of noble birth, Aru Sultan’s designation as an ambassador from the Kazakh khan to the Elizabethan court is as yet unproven. New discoveries in the English court records may eventually settle the question. But for now, this is a debate that still has a long way to run.