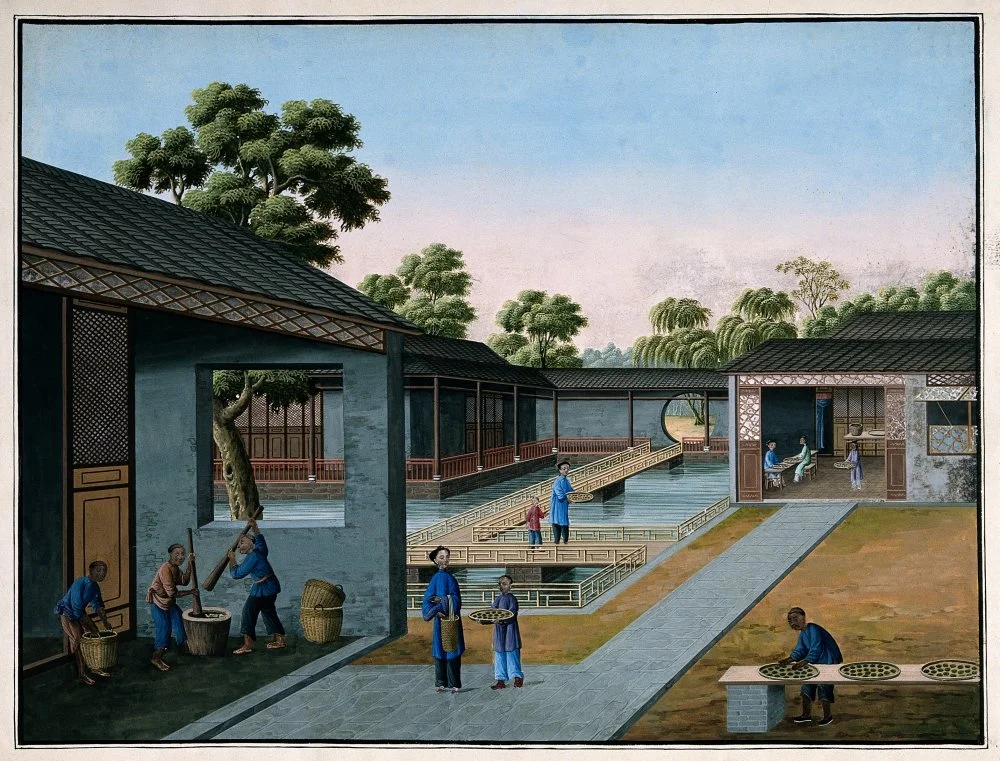

A tea plantation in China with women picking and sifting tea leaves. Gouache painting with oxidization/Wikimedia Commons

Have you ever sat around a campfire under pine canopies? That’s exactly the aroma you get when you drink hot lapsang souchong tea, a traditional Chinese tea that’s naturally smoky, without a drop of chemicals or flavorings. Of course, some critics, who lack subtlety, claim that to them, this tea smells like a railroad tie. Indeed, notes of resin and tar contribute to the tea's intricate bouquet, but that’s the very point of its unique taste.

Lapsang souchong, one of southeastern China’s most famous teas, is known by many names, including tar tea and the old spruce variety. The Chinese character for this tea represents the Wuyi Mountains, where it is carefully harvested. Harvesters selectively pluck only the uppermost, fully developed leaves, leaving the buds behind, and this is done only at the peak of summer. Optimal picking conditions involve sunny days when sea breezes waft through the area. This trifecta of warmth, sunlight, and fresh air initiates proper fermentation from the instant the leaves are plucked, and the time of harvest is typically confined to a precise window between noon and 2 p.m.

A tea plantation in China with workers grinding and balling. 19 century/Wikimedia commons

Through Fire, Water, and Pine Branches

There are two legends about the origin of this smoked tea, and no one knows which is more accurate. The first one states that about 400 years ago, a military unit was marching past a tea village at night. The soldiers were exhausted and decided to spend the night under the awnings of the peasants' courtyards, fashioning makeshift beds from sacks of freshly harvested tea leaves and soon falling asleep.

In the morning, the farmers were aghast to discover their prized crop had been crushed and, worse still, imbued with the unmistakable scent of the weary infantry. In a desperate salvage attempt, they pan-roasted the leaves in a wok (a deep, curved-bottom pan) and smoked them over pine. Little did the horrified farmers realize that this catastrophe would give birth to an extraordinary, one-of-a-kind tea. In fact, Dutch traders were so enchanted by the unusual smoky aroma that they returned to the village every year to buy the rare tea.

Three women preparing tea in a mural in the tomb of Zhang Shigu, Xuanhua, Hebei, Liao Dynasty (1093-1117)/Alamy

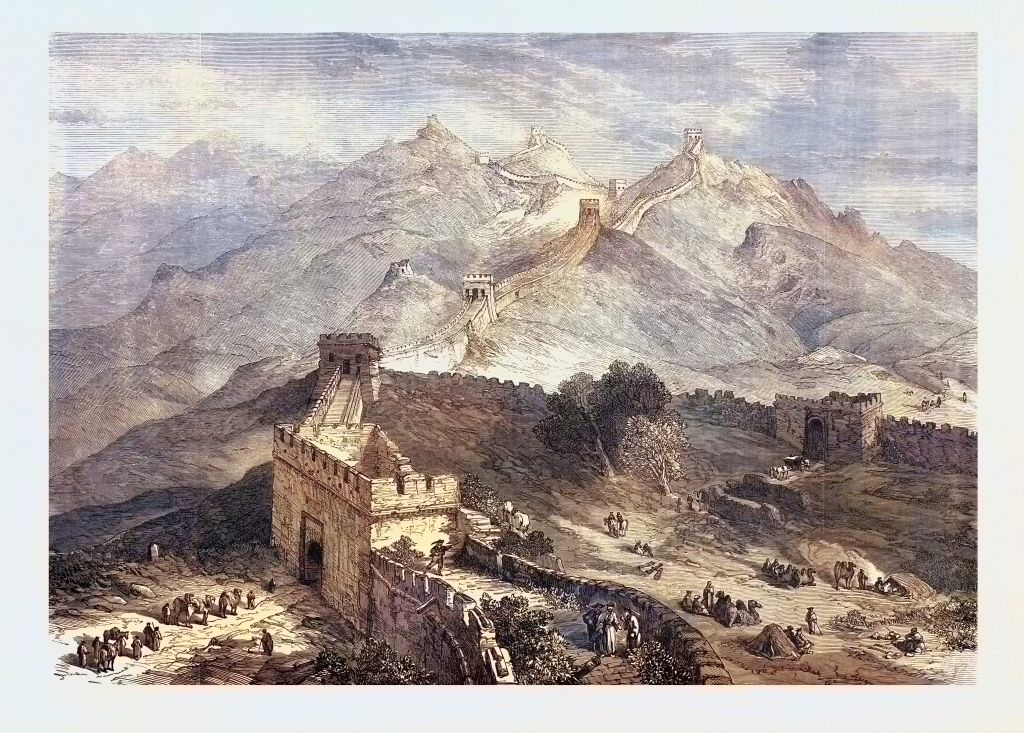

An alternative legend shares the same time frame as the first. Around 400 years ago, a tea caravan was traveling along the Great Silk Road, and the journey was grueling, made worse by mountain blizzards and biting winds. As the caravan neared its destination, the sky suddenly darkened, unleashing a relentless deluge that persisted for days. Predictably, the tea cargo was thoroughly soaked. In a bid to salvage their merchandise, the caravaners chopped down nearby pines, kindled a fire, and began drying the tea leaves. Consequently, the leaves became deeply infused with the distinctive aroma of pine trees.

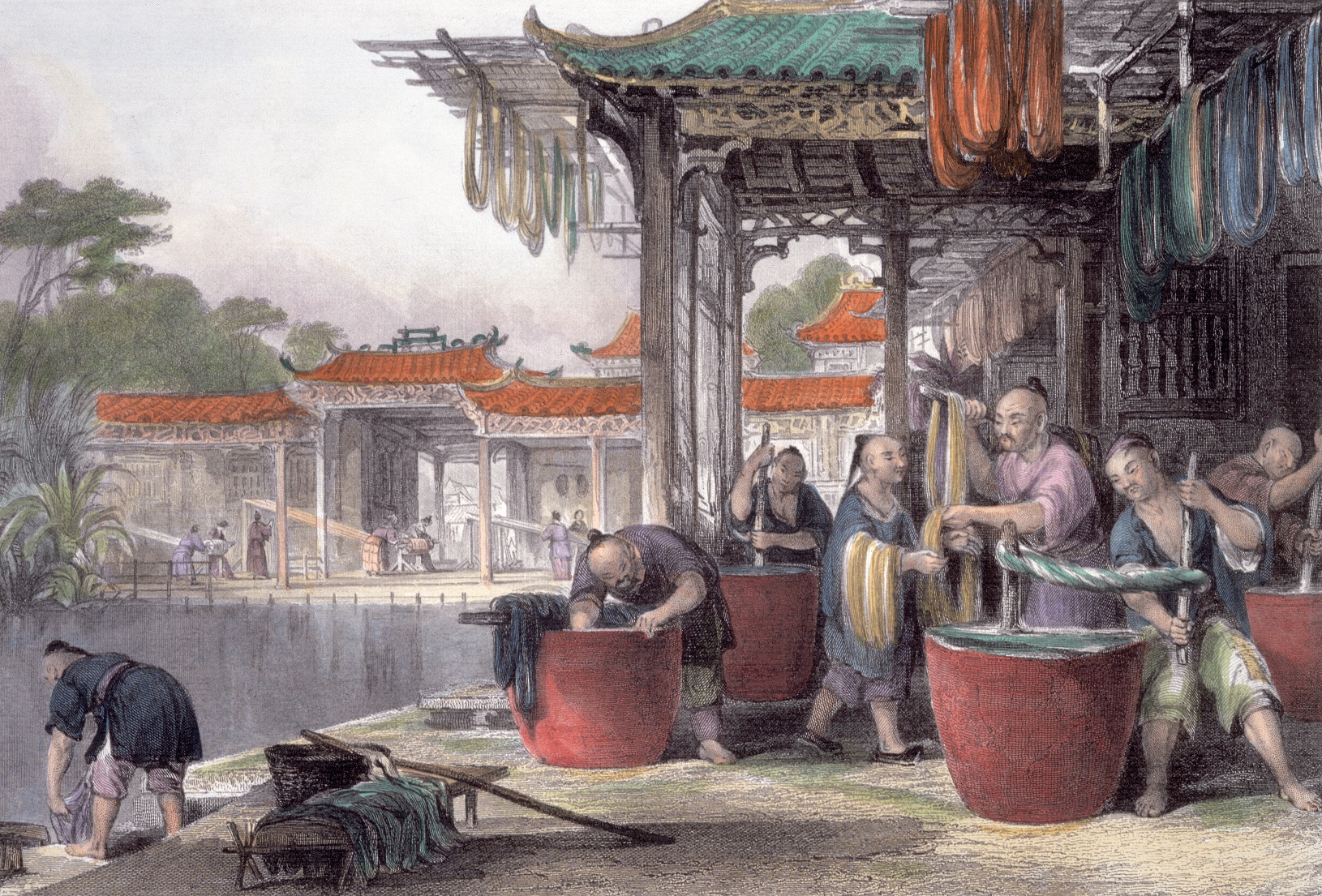

Tea production in China, Guangzhou, detail, c. 1800 AD, oil on canvas. Peabody Essex Museum, Salem/Wikimedia Commons

This incident sparked a growing demand among European tea enthusiasts for this smoked variety. By 1760, the British East India Company reported a significant shipment of 62,900 pounds (28,530 kg) of this unique tea.

So Is It Black Tea or Red?

Lapsang souchong is characterized not only by its smoky pine notes but also by the aroma of dried longan, a fruit related to the lychee. An overly smoky tea without a complex fruity undertone is almost certainly a fake lapsang souchong.

Since its leaves are as black as night, Europeans classified it as black tea. The logic is simple: if the leaves are black, the tea is black. But the Chinese have a different opinion: for them, this is red tea because in China, teas are classified by the color of the brewed beverage.

Wuyi Mountain Tea Industry Liang Junde, producer of top red tea Jinjunmei, produces Lapsang Souchong red tea, at his tea factory in the village of Tongmuguan, an area famous for the origin of red tea, on May 11, 2012 in Wuyishan, Fujian province, southeastern China/Getty Images

Typically, lapsang souchong is crafted in a wooden hut with a stove. For eight hours, the tea is warmed over pine or Chinese spruce roots. Slowly and leisurely, in the best traditions of the tea ceremony, the leaves acquire a brown color, absorbing the resinous aroma of the crackling wood.

Lapsang souchong finds its most ardent admirers among the British, and the United Kingdom is one of the principal markets for this tea.

What about Tea Eggs?

However, in the 1990s, the United Kingdom nearly lost its beloved beverage. Tea mogul Jiang Yuanshun, recipient of the Lu Yu Award (the Chinese tea industry's equivalent of an Oscar), recounts lapsang souchong's brush with extinction: ‘The 1990s were the most challenging period. The domestic tea market stagnated, leaving farmers idle. Many masters left their native lands in search of a better life in the metropolises. Vast tea plantations were left to nature's whims. Only two tea factories (one of them mine), maintained faith in the medicinal tea's value. And we were right.’

A tea farmer carries tea leaves just picked by hand on May 12, 2012 in Wuyishan, Fujian province, southeastern China/Kevin Zen/Getty Images

Lapsang souchong is especially comforting during the damp season. It is served after prolonged physical exertion in the cold and is perfect after activities like mountaineering, skiing, or building snowmen.

In Chinese cuisine, it's a key ingredient in tea eggs, a popular street food found in night markets, restaurants, and supermarkets. These are ordinary boiled eggs that are peeled and boiled again in a mixture of tea, star anise, pepper, and various spices.

The Finnish people have also embraced lapsang souchong, incorporating it into their distinctive smoked tea gin, which is distilled with tea leaves, juniper berries, and coriander seeds.

Tea enthusiasts often pair it with basturma, grilled meats, curry, or pumpkin soup. However, personal tastes vary—you might find that it also perfectly complements beşbarmaq.

A local woman cooking traditional Tea leaf eggs. The eggs are cooked in tea, Soy sauce and other spices and are a common all over China/Alamy