Today, the term ‘shala-Kazakh’ has a negative connotation and is often used mockingly or reproachfully. It refers to Kazakhs who are not fluent in the Kazakh language or who have lost part of their cultural identity. Historically, however, the term was neutral and did not imply marginality. Instead, it described the descendant of an interethnic union, a person who lived at the crossroads of cultures, languages, identities, and, often, political interests in Kazakhstan.

‘Mixed marriages’ were an important mechanism through which the Kazakh Khanate was not only established but also strengthened. These unions were formed for a wide range of reasons—from pragmatic calculation to diplomatic strategy, from necessity to personal choice, and sometimes in defiance of tradition and social expectation. This is the second part of historian Kalysh Amanzhol’s study on interethnic marriages in the territory of Kazakhstan. This time, we look at the period from the fifteenth century to the early twentieth century.

The Kalmyk Wives of the Kazakh Khanate

In the fifteenth century, when the Kazakh Khanate was first formed, the number of marriages between Kazakhs and foreigners increased. These unions were no longer limited to dynastic unions among the Chinggisid khans and sultans, for whom polygamy was customary. It was also not uncommon for foreign captives to become junior wives or concubines of rulers. One of the main reasons for this was the ongoing clashes with the Oirats (western Mongols), who would later come to be known as the Dzungars and Kalmyks.

For example, the mother of the ninth Kazakh khan, Shygai (1580–1582), was a Kalmyk woman named Abaykan-begim.

Confrontations between the Kazakhs and Oirats intensified after the Dzungar Khanate was established in 1635. By the late 1680s, the Dzungars had seized the lands of Jetisu and southern Kazakhstan, and by 1741, they had taken over part of the territory of the Middle Jüz.

Kalmyk princess. Illustration from «Caucase and Asie Centrale, Types and Costumes», a work on the people and costume of the Caucasus and Central Asia by L. Boulanger. Paris, circa 1890 / The Print Collector / Print Collector / Getty Images

These invasions led to a rise in mixed marriages, which were often forced. There were also frequent clashes between the Kazakhs of the Junior Jüz and the troops of the Kalmyk Khanate (also known as the Torgut Khanate) during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

One of the wives of the Kazakh Khanate ruler Salqam Jangir (1643–52), son of Esim Khan (1598–1628), was Banu Khanum, the daughter of the Khoshut Tayiji Kundelen-Ubashir. She gave birth to Tauke Khan, under whom the Jeti Jarğy legal code was established. Dilshah, the mother of another son of Esim Khan, Kasym Sultan, was the daughter of Kho Orluk, the first chief Tayiji of the Kalmyks, who subdued the Nogai Horde in 1628–32. Another daughter of Kho Orluk became the wife of a Chinggisid, Sultan Ishim, son of Kuchum, khan of Siberia.

Concubines and Töleñgits

Foreign female captives were generally regarded as war trophies and were known as olja. At best, they became junior wives or concubines, and at worst, slaves. The fate of captured men was no better because more often than not, they became slaves. If they were fortunate, they entered the service of the khans and sultans, in which case, they were called Töleñgits, a special warrior class directly serving the Kazakh rulers.

Akzel Beisembay. Tamga of tolengit kazakh tribe / Qalam

These social dynamics are well documented in Kazakh oral folklore. For example, the epic Jetigen Batyr provides vivid depictions of the roles of these captives, while Magjan Jumabayev's early twentieth century poem ‘Batyr Bayan’ gives us a more modern interpretation of these historical relationships. Interestingly, contemporary scholarship suggests these accounts provide insight into the complex systems of assimilation and the negotiations for status within traditional Kazakh society instead of simply highlighting the divisions between free and unfree populations.

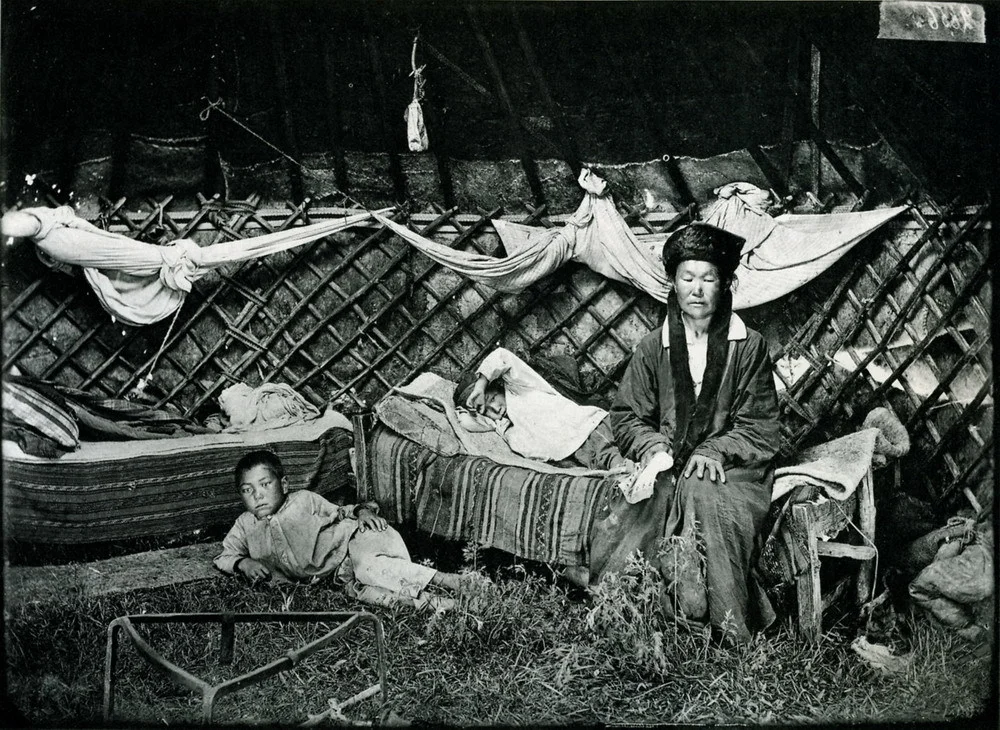

Kalmyk women in a yurt. From the London weekly «Cassell's Illustrated Family Paper». 1854 / The Print Collector / Heritage Images / Getty Images

The Wives of the Khans

Interethnic marriages were especially common within the family of the Kazakh Khanate ruler Ablyai Khan (1711–81). According to one version, his mother was the daughter of an Oirat (Kalmyk) Khong Tayiji (prince) and according to another, a Turkmen concubine. Abylai Khan himself had twelve wives, who bore him forty daughters and thirty sons. His wives came from various ethnic backgrounds, and seven of them were Kalmyk women.

Abylai Khan’s fifth wife, Topish Khanum, the daughter of Noyan Khoshuu Mergen, was betrothed to him by the Oirat khan Galdan Tseren himself. She became the mother of the sultans Qambar and Qassym (the father of the renowned Kenesary Khan). Another of his wives, Saiman Khanum, the daughter of Sagyndyq Shuaqpay, a Karakalpak bek, gave birth to four sons. Among Abylai Khan’s wives were also the daughter of a Kashgarian bek, Kenje Sart, and a Russian concubine.

The mothers of some of Abylai Khan’s most well-known comrades, such as Qabanbai and Malaisary, were of Kalmyk origin. Qabanbai’s mother was named Künbike, and Malaisary’s mother was called Möldir. Such marriage alliances were also common among the ruling elite of the Junior Jüz.

Abulkhair Khan’s (1718–48) first wife was Bopai Khanum, while his second wife was a Kalmyk woman named Bayan Khanum, who gave birth to Shyngys Sultan. Nuraly Khan (1748–86), Abulkhair’s eldest son, was married to a Kalmyk woman named Ryss (Yrys), who had been taken captive and became the mother of his son Qaratay.

The Turkic Wives of the Kazakh Khanate

Mixed marriages were also widespread along the borders of the Kazakh Khanate, particularly with other Turkic peoples. These included the Kyrgyz, Bashkirs, Karakalpaks, Turkmen, Nogais, and Tatars. Such marriages took place both peacefully, especially in the border regions, and as a result of raids by Kazakh sultans and khans, as well as through migratory movements across Kazakhstan, especially during Abylai Khan’s time.

For some, these marriages were an opportunity to forge new alliances, secure protection, or integrate into powerful lineages, and for others, they were acts of coercion. Yet whether they emerged from diplomacy or force, these unions became threads in the vast tapestry of Eurasian cultural exchange, binding communities together even as empires rose and fell around them.

According to Shokan Ualikhanov, in the mid-1750s, Abylai captured several hundred Kyrgyz prisoners during one of his raids, whom he settled into two volosts of the Kökshetau district, Jana Kyrgyz and Bai Kyrgyz. These groups later became part of the Atygay clan of the Argyn tribe.

A similar settlement of ethnic Kyrgyz, who had intermingled with the indigenous Kazakh population, took place in other regions of Kazakhstan—central, eastern, southeastern, southern, and western— as well.

For example, a renowned public figure of his time, Monke Tleuuly (1675–1756)—a jyraui

The Assimilation of the Bashkirs and Kazakhs

In addition to interethnic marriages, there was also a powerful blending of cultures between neighboring peoples in Central Asia, and nowhere is this more evident than in the assimilation process between Kazakhs and Bashkirs. Their connection was woven through centuries of contact, friendly relations, shared tribal affiliations, national liberation wars, as well as tragic periods when these peoples were incited against each other by the tsarist administration. Nevertheless, despite all the upheaval, Kazakhs and Bashkirs continued to migrate to each other’s territories throughout the eighteenth century.

Ivan Zelenov. Element of Bashkir national costume — inghalek (yelkalek). «Young married woman in festive costume». Ufa Governorate, Belebeevsky district, village of Yabalakly. 1909 / Wikimedia Commons

The suppression of national liberation uprisings between 1735 and 1740, and again in 1755, saw approximately 10,000 Bashkirs seek refuge among Kazakh clans in the western and partially northwestern territories of Kazakhstan.

According to the records of the Orenburg Border Commission for the years between 1799 and 1815, a total of 1,226 Kazakhs (863 men and 363 women) were assigned to the ‘Bashkir’ population of various villages of the fourth, sixth, and ninth cantons. Most of them were from the tribal groups of the Junior Jüz, such as the Jağalbaily, Tama, Tabyn, and Shekti clans, as well as Qypshaqs (Kipchaks) from the Middle Jüz. Many of them had formed marital unions with Bashkir women who had been taken captive at various times.

Among the Bashkirs, there are still tribal ethnic groups known as ‘Kazakh’, preserving ancestral connections that span centuries. Similarly, many Kazakhs are descended from Kazakh-Bashkir families, particularly in Western Kazakhstan, where tribal ethnic groups like the Estek bear witness to this shared history.

Unions Between Kazakhs and Turkmens

There are numerous examples of close ties between Kazakh and Turkmen tribal groups. These interactions significantly increased after the conquest of the Khorezm state by the Shaybanids in 1505.

Er Kosai Kudaиkeuly (1507–94), born to a Turkmen mother, became one of the leaders of the Mangystau Adai clan, a batyr, and advisor to Khaknazar Khan (1538–80). He was married to Ogulmenlig, the daughter of the Turkmen leader Er Sary. Their descendants laid the foundation for the Turkmen Adai line.

During the turbulent military and political landscape that played out from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, at the time of the Khivan and Kazakh khanates, as we discussed before, some Turkmen women became wives, concubines, or slaves. Turkmen men, as was also the case with the Oirats, became toleńgits. Others, through intermarriage with Kazakhs, joined local tribal structures, identifying themselves as descendants of the Alimuly branch of the Junior Jüz or the Jalaiyr clan of the Senior Jüz.

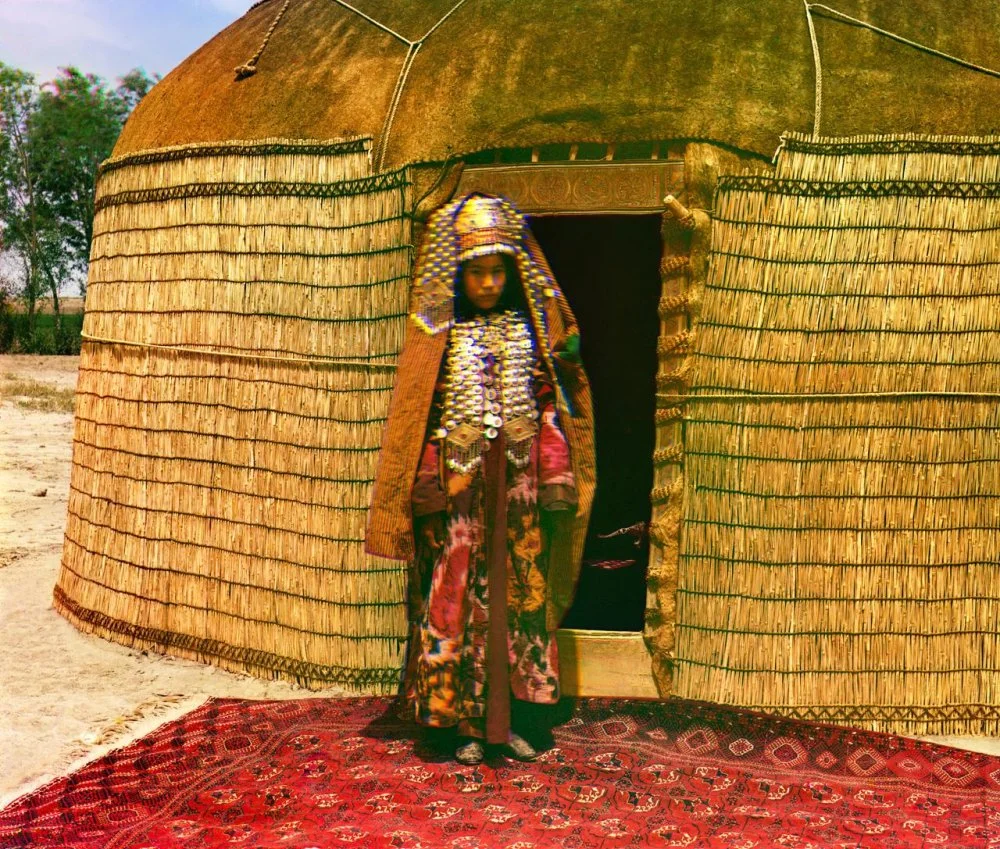

Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky. Young turkmen woman in traditional dress and jewelry standing at the entrance of a yurt. Turkestan, circa 1905–1915 / Heritage Images / Getty Images

Kazakh-Nogai Unions

Stable relations between the Kazakhs and Nogais had already been established during the rule of the Kazakh Khanate and the Nogai Horde in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and endured into the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as well. This connection, one of the most culturally significant in the Eurasian steppe, was rooted in their shared ethnic origins, linguistic kinship, cultural similarities, common customs, traditions, and oral folklore.

Nogai girls in traditional dress. Beginning of the 20th century / Wikimedia Commons

The works of prominent steppe poets, such as Shalkiiz Jyrau (1465–1560), Dospambet Jyrau (1490–1523), and Kaztugan Jyrau (1500s), epitomize the shared cultural heritage of these peoples. This cultural affinity also facilitated widespread bidirectional migration, with entire clans periodically shifting between Nogai and Kazakh domains, leading to numerous mixed marriages.

Kyrgyz People. Kyrgyzstan, 1910s / Romanov empire

By the nineteenth century, medieval Nogai ancestry had become firmly embedded within Kazakh tribal structures, particularly visible in the Junior Jüz's Jeti Ru (Jagalbaily and Teleu clans), Alimuly (Sherkesh and Karakesek clans), and Baiuly (Altyn, Jappas and Berish clans) divisions, as well as among certain Qoñyrat clans of the Middle Jüz.

By the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries, they inhabited not only western Kazakhstan but also the northern regions (Kökshetau and Qostanay districts), eastern areas (Semei district), southeastern territories (Lepsinsk district), and southern zones (Shymkent district). This wide distribution transformed the Nogai legacy from a localized phenomenon into an integral part of Kazakhstan's broader ethnic tapestry.

Marriages with Tatars

Kazakh-Tatar families are another example of unions based on ethnocultural and religious factors, with roots tracing back to the Middle Ages.

The renowned poet, philosopher, and jyrau Asan Qaygy Sabituly (1370–1465)—who served as advisor to the khan of the Golden Horde and founder of the Kazan Khanate, the Chinggisid Ulugh Muhammad (1405–45)—was considered kin by both Kazakhs and Kazan Tatars. Asan Qaygy’s mother, Sabira, was the younger sister of Ulugh Muhammad.

In the nineteenth century, one of the most notable examples of such a union was the marriage of Khan Jangir Bökeiuly (1801–45), the last ruler of the Bukey Horde with Fatima Khanum, daughter of the well-known Orenburg muftii

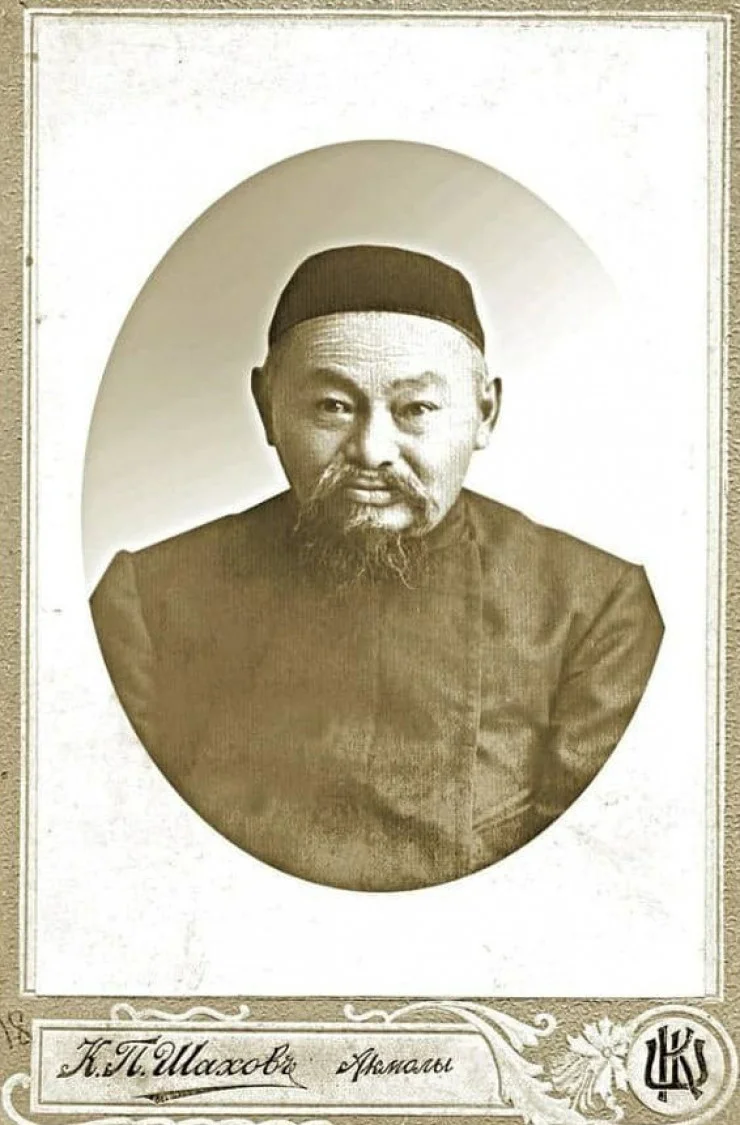

Baimukhambet Kosshyghulov / vechastana / cyclowiki

Later in the century, another famous example of an interethnic union emerged with the wedding of the Kazakh merchant and philanthropist Baymukhambet Kosshygulov (1848–1916), from the Karaotkel region of the Akmolinsk province, to Madina Maksyutova, the daughter of the Tatar merchant who had raised Kosshygulov after he was orphaned.

Kazakh Wives

In different parts of Kazakhstan, not only were marriages with foreign women common, but unions between Kazakh women and men from different—mostly Turkic—ethnic groups also regularly took place. From the eighteenth to early twentieth centuries, these groups included Tatars, Bashkirs, Nogais, Karakalpaks, Turkmens, Uzbeks, Kyrgyz, Uyghurs, and Altaians.

For instance, Wali Khalfin (1834–94), a Tatar merchant and prominent educator from Akmolinsk, was married to a Kazakh woman named Taurbala Balkymbaиkyzy, the daughter of a wealthy livestock owner. She bore him six sons.

Marriages between Kazakh women and Sarts (Tajiks), Russians, Cossacks, Ukrainians, Kalmyks, and Dungans were also recorded. The descendants of such mixed families—where the wives were Kazakh and the husbands belonged to other nationalities—were commonly referred to as shala-Kazakhsi

Samuil Dudin. Kazakhs of the Semipalatinsk Region. 1899 / Romanov Empire

The study of historical data, dating back to the Proto-Turkic period, confirms that for over 2,000 years, in addition to monoethnic marriages, there were also many polyethnic, mixed unions in the territory of present-day Kazakhstan. Mixed marriages were far more common among the ruling elite and their immediate circle, including nobles, bis, batyrs, and other officials, many of whom had multiple wives and concubines.

Kazakh yurt in the Nogai steppes near Astrakhan. 1894 / Romanov empire

The primary motivation behind such marriages was to strengthen political alliances between states.

Among ordinary people, such marriages were significantly less frequent. Typically, they occurred in regions of ethnic contact with neighboring tribes and peoples. In some cases, these unions arose from military conflicts, in which female captives were integrated into a household and could eventually gain the status of wife.

This long-standing tradition of mixed unions has left a lasting impact on Kazakh society, and even today, the legacy of these ancient interethnic ties lives on in family genealogies, in borrowed words used every day, and in shared customs that continue to unite the peoples of Central Asia.

This is the second part of historian Kalysh Amanzhol’s study on interethnic unions in the territory of modern Kazakhstan. The first part, covering interethnic alliances from the third century BCE to the fifteenth century, can be found here.