For centuries, the land that is now Kazakhstan stood at the intersections of great migrations, trade routes, and military conflicts. These processes inevitably brought people together in mixed marriages, some of which were voluntary, others forced. In this region where empires rose and fell, marriage was often more than a matter of the heart—it was a tool of grand politics. Chinese princesses married Turkic khagans, Mamluk sultans married the daughters of the rulers of the Golden Horde, while Kazakh khans took wives from the very nations they fought against.

Historian Kalysh Amanzhol reveals how these cross-cultural marriages shaped alliances, softened conflicts, and sometimes changed the course of history.

Proto-Turks and Chinese Princesses

From the third century BCE to the second century CE, the territory of Eurasia, including what is now Kazakhstan, was inhabited by proto-Turkic tribes including the Xiongnui

History records several wars between the Xiongnu, who lived in the eastern Eurasian steppe, and the Chinese, but there were also marital alliances between the representatives of these peoples. For example, among the wives of Modu Chanyui

Gu Hongzhong. Night Revels of Han Xizai (detail). The original 10th-century work no longer survives; this version is a 12th century Song Dynasty copy / Photo by Pictures from History / Universal Images Group / Getty Images

The Huns were not the only ones to take women from the Chinese court as wives. We know of several cases in which Chinese princesses married the gunmo, the supreme rulers of the Wusun tribe. The motivation was the same: to preserve good neighborly relations. Similarly, in the state of the Kangjui

This practice continued in later periods as well. The rulers of the Rouran Khaganate, an early Mongolic state, also recognized the advantages of interdynastic marriages, not so much as a way to strengthen alliances, but rather as a fairly reliable means of delaying war.

Marriage as Geopolitics

In the Turkic Khaganate, dynastic marriages were a key component of foreign policy. In 551, Bumin, the founder and first khagan, secured a dynastic marriage with the Chinese princess Changle, daughter of Emperor Wen-di of the Western Wei state. His son and successors continued forming such alliances, marrying princesses from the Northern Zhou, Sui, and Tang dynasties.

Detail from Banquet and Concert, depicting elegant ladies of the Tang imperial court enjoying a feast and music. China, 10th century / Werner Forman / Universal Images Group / Getty Images

At times, a single woman would become the wife of several rulers. One particularly interesting case is that of Princess Yicheng Khatun from the Sui dynasty. In 599, she became the wife of Yami Qaghani

There are sources confirming even more distant connections—for example, the Eastern Turkic khagan Illig was betrothed to Augusta Epiphania, the daughter of Byzantine emperor Heracliusi

Moreover, the rulers of the Turkic Khaganate did not only enter dynastic unions themselves but also arranged marriages with foreigners for members of their ruling elite. A monument inscribed in Old Turkic runic script, dedicated to Kül Tegini

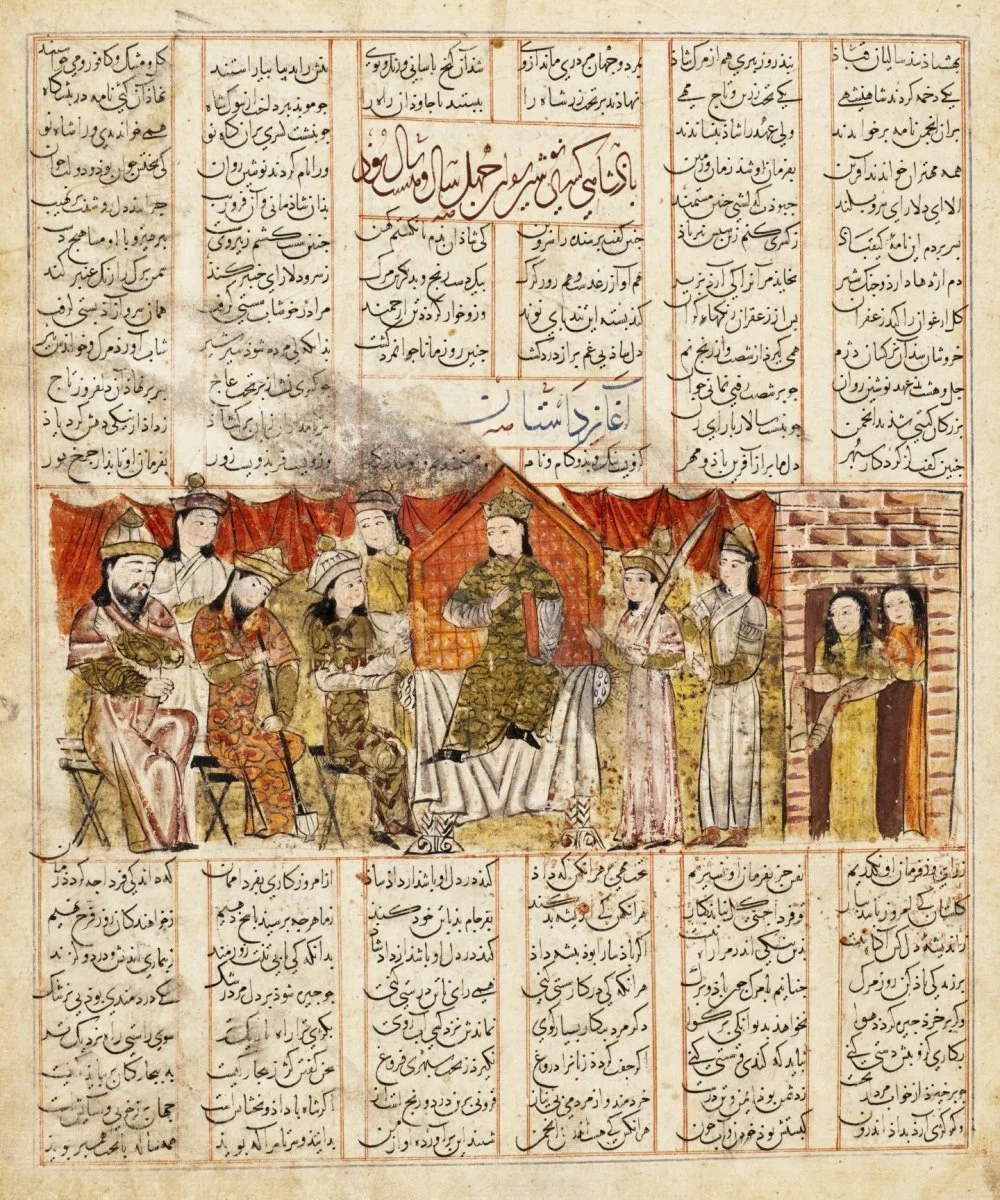

King Khusraw Anushirvan Enthroned. Page from a manuscript of the Shahnama (Book of Kings) by Ferdowsi, ca. 1341, Iran, Shiraz / Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) / Wikimedia Commons

The significance of interdynastic marriage alliances among the Turks was also preserved in their relations with Western powers. Thus, around the year 562, the Western Turkic Khaganate ruler Istämi Khagan is believed to have given his daughter in marriage to the shahanshah (meaning ‘king of kings’) of Sasanian Iran Khosrow I Anushirvani

Indeed, the geographical reach of Turkic dynastic ties reached far beyond neighboring states. During the existence of the Türgesh statei

Steppe Brides in Europe

The tradition of mixed marriages actively continued into the late Middle Ages. The Karluks, Karakhanids, Kimeks, Oghuz, and Kipchaks—nearly every major Turkic state of the time—formed dynastic alliances with neighboring powers. For example, the Karluk yabghus and local rulers (756–940) entered into dynastic marriages with members of the Sogdian elite, helping strengthen political and cultural ties. The Karakhanids actively cooperated with the Chinese Liao dynasty, with historians counting around forty diplomatic missions between the two. In one such mission, the Karakhanid heir to the throne married a Chinese princess.

The Oghuz, who controlled territories stretching from Iran to Byzantium, also entered into alliances with various peoples and gave rise to dynasties such as the Seljukids and Ottomans. The Kipchaks are the best-documented in terms of dynastic marriages. The earliest records date to the eighth century and describe alliances with the Tatars.

Later, in the eleventh to twelfth centuries, Kipchak khans regularly gave their daughters in marriage to the princes of Kievan Rus and later to rulers of the Grand Principality of Vladimir. These unions played a significant role in strengthening political and military-diplomatic relations between the steppe and the Slavic world.

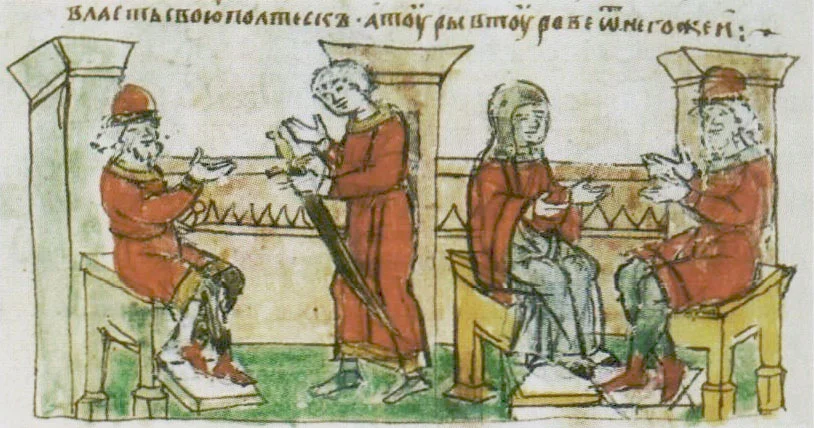

Miniature from the Radziwill Chronicle: on the left — envoys of Vladimir of Novgorod visiting Rogvolod of Polotsk; on the right — Rogvolod speaks with Rogneda, who refused to marry Vladimir. Rogneda was the daughter of Knaz Rogvolod, a ruler of Polotsk in the 10th century. Some sources suggest her family had Varangian-Slavic or even Khazar ancestry. Her forced marriage to Prince Vladimir of Kievan Rus’ is an early example of political and interethnic unions in Eurasia, resonating with the later traditions of mixed marriages in steppe cultures, including the Kazakh lands / Wikimedia Commons

The princes of Pereyaslavl, Vsevolod Yaroslavich, and Vladimir Vsevolodovich Monomakh, were among the first to marry daughters of the rulers of the Desht-i Kipchak. A few years later, in 1094, Grand Prince Sviatopolk II Iziaslavich of Kiev concluded a similar alliance by marrying the daughter of Khan Tugorkan. Over time, such marriages became almost a political tradition.

Mikhail Sabinin. St. King David IV the Builder. 1882 / Wikimedia Commons

The princes of ancient Rus were not the only Christians to marry Kipchak women. In 1103, Gurandukht, daughter of the Kipchak khan Otrok, married King David IV the Builder of Georgia. Along with her, 40,000 Kipchak warriors came to Georgia, helping David achieve one of his most important victories against the Seljuks. This alliance is widely regarded as having saved the Georgian kingdom.

Marriages as a Means of Survival

Between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries, mixed marriages became a prevalent phenomenon, and this was not only for political or dynastic reasons. Prolonged conflicts during this time often led to the taking of captives, forced resettlements, and new forms of coexistence. As a result, marriages between people of different ethnic backgrounds became either a political strategy or a simple necessity. Such unions were especially common among the elite, including Chinggisids, sultans, biys, and batyrs.

During this period, the Golden Horde established stable diplomatic and political ties with the ruling elites of more powerful states, including the Bahri Mamluk Sultanatei

Mamluk court scene at the time of Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad. Illustration from «Maqamat of al-Hariri» / Probably Egypt, c. 1334 / Wikimedia Commons

Historian Marie Favereau spoke about the role of women in these unions in an interview with Qalam. According to her, unlike in Byzantium, where the marriage of princesses was primarily a matter of policy, women in the elite of the Golden Horde often held genuine agency:

In Byzantium, the marriage of princesses was often little more than a function of the political machine, with the woman’s own will not always taken into account. Among the Mongols—especially within the upper echelons of the Chinggisid elite—the picture was strikingly different. These women were influential figures, and all evidence points to the fact that they were not forced into marriage against their will. Such unions were the subject of lengthy negotiations, particularly when the bride came from a powerful lineage. It seems that what mattered was not only the political weight of the alliance, but also the woman’s own consent.

This is the first part of historian Kalysh Amanzhol’s research on interethnic unions in the territory of present-day Kazakhstan in earlier times. In the second part, we will examine the prevalence of mixed marriages from the fifteenth century to the early twentieth century, starting with the Kazakh Khanate and continuing through to the Revolution of 1917.

Vittore Carpaccio. Two Standing Women, One in Mamluk Dress / Princeton University Art Museum / Wikimedia Commons