In the lecture series Medieval Art of the West, historian and medievalist Oleg Voskoboynikov presents both significant and lesser-known monuments of artistic culture from the Middle Ages, offering insights through the medieval person’s perspective. The third lecture explores questions such as how medieval artists knew what angels looked like, how they depicted the torments of hell, whether illiterate parishioners could ‘read’ the Bible through stained glass and frescoes, and the true function of these depictions.

The role of scripture in medieval art raises questions about issues of models, topoi, and canons. The medieval consciousness cannot be reduced to the Bible and yet, the Bible can explain almost everything about it. The Bible was not known by all, but many scholars, writers, preachers, and hermits knew it almost by heart since reading scripture was their daily spiritual exercise, aimed to train their memory and imagination. When reading certain medieval texts, today’s readers risk drowning in biblical quotes. However, medieval thinkers did not drown in them; instead, they floated freely through biblical texts, which often grew to determine their thought processes. Even if taken out of context, a well-chosen quotation could describe any life situation, philosophical concept, or feeling literally or metaphorically. Those who aspired to be educated started out with the psalms, proceeded through the seven liberal arts, before returning to scripture. It was often said that scripture contained all the possible wisdom that man could acquire; however, this did not subjugate and restrict the will for intellectual renewal and progress. For example, in some ways, revelation was arcane—sacred knowledge had to be discovered, understood, taught, and implemented into people’s lives. The medieval exegesis (or interpretation) of the Bible came into being during the first centuries of the modern era, and would later be developed and distributed extensively.

We must imagine that combinations of three or four words from the scriptures would evoke semantic syntagma in the memory and imagination of someone born in the twelfth or thirteenth centuries in exactly the same way that someone with a literary education today could instinctively complete, whether out loud or in their heads, a familiar fragment from a beloved poet. And often, a few words can mask an entire dogma or world of images in a concentrated form.

Art became an integral part of this exegesis and the worldview of an European associated with it.

«Novelty in the old, and antiquity in the new»

Is how Confessor Paulinus of Nola expressed himself through his poetry during the twilight of antiquity. This expression referred to the iconographic program of the newly built basilica in Chimitil, where the clerestory was decorated with Old Testament scenes, while the old temple was decorated with stories from the New Testament. The exegesis of the New Testament primarily sought to understand Christianity through a multilevel interpretation of the Old Testament books, viewing them as prophecy. Art—in literal, historical, allegorical, and moral terms—reflected the ‘old’ through the ‘new’ and the ‘new’ through the ‘old’. Murals also followed this principle, placing scenes that were related by typology from the two covenants next to one another. If required, similar typologic parallels were drawn between the exploits of a saint and gospel history, the earthly feats of Christ and the apostles. The walls of the Basilica of Assisi (circa 1300) depict scenes from the lifetime of Francis to demonstrate to spectators that it is first necessary to give up earthly endeavors in order to create miracles here and gain eternal life in heaven (ill.). It is also important that the viewer can see their beloved saint depicted in the same place exactly where Christ, the Mother of God, and the apostles are usually depicted.

Francis gives his cloak to a once rich, now poor warrior. Fresco from the Basilica of St. Francis. Italy, Assisi, 1295-1300 / Fine Art Images/Legion

At the same time, no one could depict all the holy scriptures or even the whole gospel history on church walls or the pages of manuscripts. As a result, the selection of scenes provides insight into the medieval mind, and we must analyze it based on its specific context when studying a particular program, whether a mural, mosaic, or a sequence of miniatures. We must ask ourselves why one sequence focuses on Christ’s childhood, the other on his miracles, and the third on the Passion. One era or school reveals the gospel, concentrating only on that which is essential without being distracted by secondary detail. Another, meanwhile, introduces a great many everyday details into the scenes, whether just to indulge the curiosity of the audience or to address certain exegetic and didactic objectives in preaching.

What Function Does the Depiction Serve?

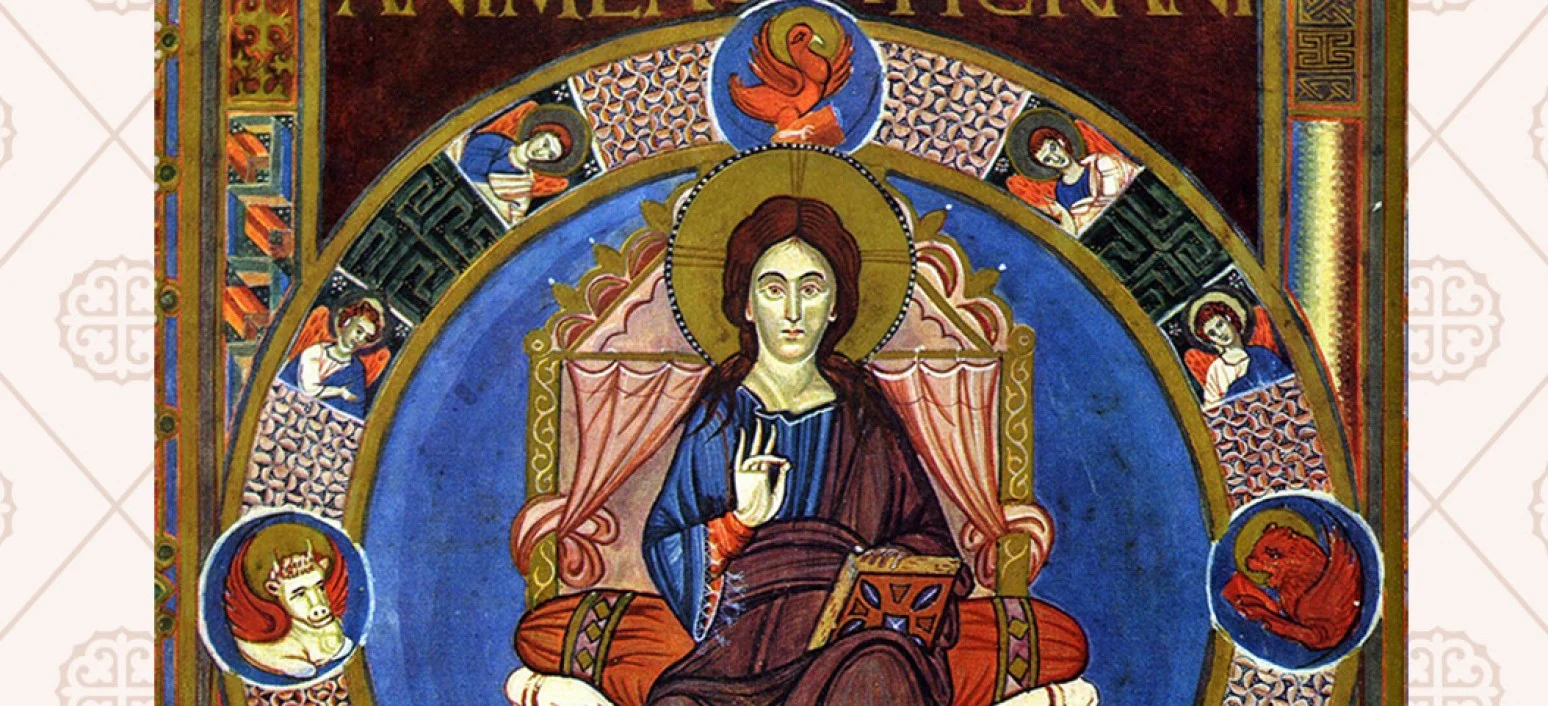

Depictions of gospel sequences were a favorite of the Ottonian era in Germany, and some magnificent illuminated manuscripts from the turn of the tenth and eleventh centuries have survived. Many of the scenes are truly striking, conveying the great spiritual concentration of the artists and those—from Benedictine monks to emperors—who commissioned their work. These scenes are still terse and concise in their own way, with each gesture expressive and easily read. The figures of the people themselves, as Hans Jantzen once put it, have been transformed into the ‘embodiment of gestures’.

The sequences became more expansive later in the Middle Ages, and the taste for story-telling increased from generation to generation. This reached almost the maximum level in Sainte-Chapelle, Paris in the 1240’s, where an entire, extensive construction was covered with sacred stories depicted in stained glass – an architectural reliquary for the Crown of Thorns which had just been brought to the site from Constantinople. The richness and perfection of this pictorial narrative proved to be a trap – no one could read a Bible such as this from beginning to end, let alone try to figure out what the core lesson or overall idea was, or even some kind of guiding thread. It wouldn’t occur to anyone to attempt to read a sermon based on these windows.

Stained glass windows of the upper part of the St. Chapel in Sainte-Chapelle. France, 1242-1248 / Alamy

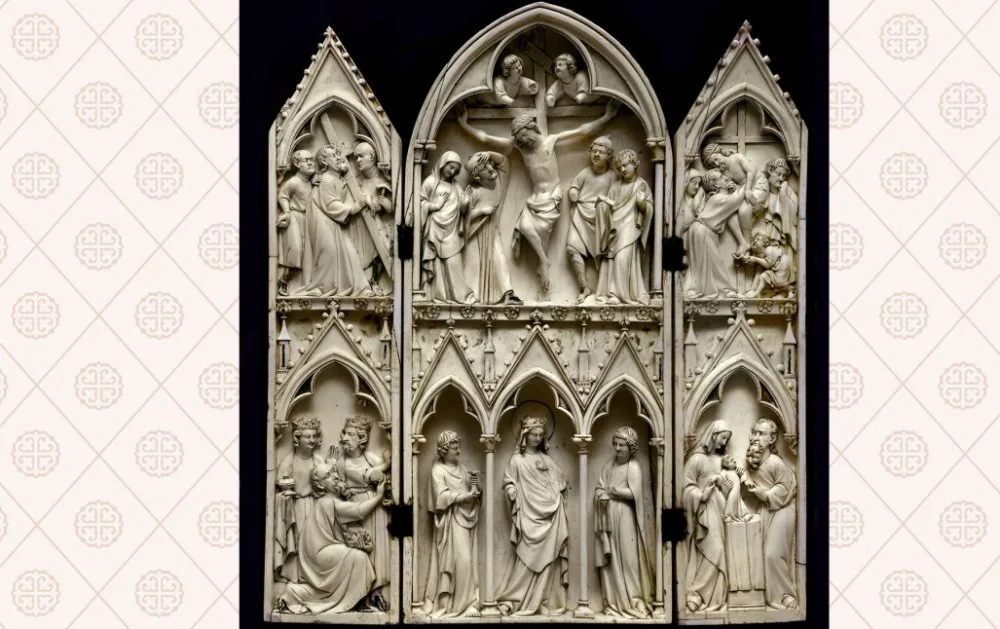

Occasionally, in some special work, for example, on the metal cover of a liturgical manuscript or even on a single plate of ivory, one may find almost an entire eschatology, that visual reflection on the fate of humanity and the final judgment. On this eleventh-century plaque from the Cluny Museum, we see the crucified Christ in the center, the sun and the moon symbolizing the universe, and the many hours of eclipse. More unusually we also see myrrh-bearing wives at the tomb, the ascension of Christ, and the second coming.

The carver (and the abbot or bishop who commissioned the work) described a specific event on earth—the death of Christ—and across the three scenes he described the resurrection and what, as a result, was waiting for us in some detail. And these three essential scenes are not located on separate plates but within a single storyline. This is not a sequence of different if related events—it is a single ‘iconic’ meta-image and meta-story, both verbose and concise at the same time.

The tricuspid portable altar "The Virgin in Glory" from the church of Saint-Sulpice du Tarn. Paris. The end of the 13th century. Ivory. The Cluny Museum / /Alamy

In painting and sculpture such peculiarities and even paradoxes of biblical narratives may hide the peculiarities of the worldview and culture of a particular period or region of medieval Europe. An interesting text that indicates this traditional practice of medieval art has survived. Around the year 1200, an English Cistercian (probably Adam of Dore OCist) was furious about the frivolity of the artists and sculptors of his time and so he outlined rules that should be followed to correlate the typology of certain scenes from the new and old testaments through the didactic poem 'The Artist in Verses' (Pictor in Carmine). In the manuscripts, the gospel episode is highlighted in red or moved to the margins, and attached to it are Old Testament episodes concisely marked with the same short phrases. However, it is much more interesting to understand how monks and some church authorities viewed the work of artists through a small but eloquent preamble by the author explaining the purposes and objectives of the poem. Here is the text in full.

‘Mourning the fact that in the sanctuaries of God instead of grace you often encounter all kinds of absurdity and ugliness, I have decided that to the greatest extent possible I shall give the mind and vision of believers more decent and healthy food. Since our contemporaries' eyes are drawn to all sorts of nonsense and worldly trifles, and we can’t just remove the worthless paintings that are in our churches today, I think that in cathedrals and parish temples where services take place we can tolerate such images which delight believers and, like books for the layman, reveal divine meanings to common people and teach the educated to love scripture. Here are just a few examples. And indeed, what is more worthy, more useful to find peering over the altar of God—two-headed eagles, lions with four bodies but one head, centaur-archers, raging Acephalites, sneaky and logical chimera, fables about the amusement of fox and cock, monkeys playing flutes and Boethius’s donkey next to a lyre?i

‘In order to discourage this overindulgence by artists, or rather to teach them what to depict in churches and where images are possible, I paired up testimonies of events from the Old and New Testaments, with couplets above that briefly explain Old Testament history and connections with New Testament history. I have by request also combined this work into chapters, so various couplets can be combined under one title, and if any storyline has been covered too briefly then the reader will find enough material in the next instance. These distiches are mainly devoted to the Old Testament, because the New Testament is more familiar and well known so it is sufficient to mention the names of the characters concerned. It is not my intention to tell those responsible exactly what they should depict in churches—let them decide for themselves based on their gut instinct. The main issue is that they seek Christ’s glory and not their own, and then He will give them praise not only from the mouths of suckling babes. Even if the suckling babes are silent, the stones will cry out and the wall decorated with testimonies of the greatness of God shall speak of them. In many churches I have been forced to fix paintings that had already been started to make them respectable, and correct depraved vanity with things spiritual.’

This 'symphony' was aimed at people who knew scripture well, employing traditional poetic forms for didactic purposes and facilitating easier memorization. The author is familiar with the tradition of Gregory the Great, according to which art teaches the illiterate but also recognizes that church painting can inspire the cultural elite. We can also see that this elite knows the New Testament better than the Old Testament, but it is the combination of the two that can awaken religious zeal inspired by a sermon. It is no coincidence that the military victories of the Maccabees and the 'deeds of the Lord our Savior' are mentioned in the same line. What do they have in common at first glance? This is what we mean by a typological reading of scripture through the medium of art, the aim of which is to describe and preach about salvation. This function could be labeled by the difficult-to-translate medieval word ‘compunctio’, which means that looking at pious images should cause believers to focus themselves spiritually on scripture, causing a reaction which in Russia is traditionally known as 'contrition of the heart' and was taken from Psalm 34.

The so-called 'moralizing' or 'moralized Bibles' i

A series of luxuriously illustrated manuscripts was created for the French royal family during the 1220s and 1240s, to which the concept for the stained-glass windows at Sainte-Chapelle is justifiably linked. In these large-format codexes, stretched over hundreds of pages, the story of the Bible is told through very brief references to biblical texts in French placed next to one another in the border scenes. All the scenes are interwoven into an inextricable whole, forcing a specific rhythm of thought and visual processing on readers and viewers (ill.). In the columns to either side of the miniature 'stained glass', which consisted of eight marginal scenes, the king had neatly written passages from sacred history inscribed alternating with moral explanations. The miniature, which featured eight scenes and dozens of characters on a single sheet, was devoted largely to the comparison of stories in the Old and New Testaments that were somehow related to the same moral issue. It is impossible to imagine reading a Bible like this in the order we’re used to—the hermeneutics of it are simply too complicated.

Many medieval thinkers, starting from Pope Gregory the Great, saw the main task of religious art in 'historicism' and moralizing. And indeed, religious art remained true to its task, but this wasn’t its only purpose. When necessary, medieval artists were not afraid to supplement the content of the Christian revelation with images of pagan origin or use teachings or texts not officially recognized by the Church, namely the Apocrypha. The exceptionally popular apocrypha 'Visions of the Apostle Paul' (Visio Pauli) played a significant role in influencing iconography and the overall representations of the supernatural world, especially with regard to hellish torment. The quintessence of this was Dante’s Divine Comedy, which was also a frequent subject for illustrations.

Nobody doubted the existence of angels, but it doesn’t say anywhere in the Bible that they have wings. The imagination was applied to 'assign' them wings as a necessary tool for flight, with ancient artistic tradition providing assistance through Nike, the winged goddess of victory.

Nike, goddess of victory. Turkey, Ephesus, 1st-2nd century AD / Wikimedia Commons

The key features of the role of medieval art and its relationship with the overall worldview of the time exhibited itself through the combination of a sincere attachment to the letter and spirit of the Bible, a rich imagination, and a keen interest in the heritage of ancient peoples. Medieval man cherished both knowledge and faith. He wanted to be shown what he believed in. This meant that what he couldn’t see within nature would have to be provided by theology, through the imagination of the preacher and the ingenuity of the artist. When describing the appearance of an angel—young, beautiful, dressed in light clothes, and winged—a medieval thinker would refer to both reverends and painters. As Michael Scot (lat. Michael Scotus) wrote in 1235: 'Look how they are depicted by painters: winged, with feathers and large eyes, singing and moving like the wind'. It may seem clichéd—sure, let them be winged. Yet, in the 1430s, Jan van Eyck somehow dared to depict an angelic choir as wingless

Jan van Eyck. Singing angels. The Ghent Altarpiece (Fragment), 1432 / Alamy

Why? To demonstrate what he could do? I think this already speaks to the audacity of a new time—the autumn of the Middle Ages, the urban civilization of Flanders—where an artist was actually a theologian with a brush in his hands. However, this artist-theologian still had the same traditional function: to portray the unimaginable and describe the unseen. As Hugh of Saint-Victor wrote in the seventh century, 'Visible beauty is an image of invisible beauty'.