In the lecture series Medieval Art of the West, historian and medievalist Oleg Voskoboynikov presents both significant and lesser-known monuments of artistic culture from the Middle Ages, offering insights through the medieval person’s perspective. In the fifth lecture, the author delves into the manifold meanings of the primary Christian symbols.

In any general history of art, we will find medieval art being described as symbolic. Let us consider this statement. Throughout the early Middle Ages, the dominant way to understand the universe was through symbols. However, even in the late Middle Ages and on the eve of the modern age, even though symbolism had significantly lost out to the spread of new knowledge, it did not dissolve into empiricism; it was instead transformed and enriched. In this respect, medieval civilization is not alone because without exception, symbolism is inherent in more or less all cultures. It is based on the belief that any event has several additional aspects beyond its core content. This conviction is collective if only because the word ‘symbol’ begins with a connecting prefix, signifying thought and the involvement of numerous participants in this communication. The nature of each individual’s communicative situations define and determine the degree of literalism or, conversely, the figurativeness of a word, gesture, or image, and this is relevant to any work of art or any subject. However, it would be a profoundly misleading assumption that medieval art is symbolic as opposed to the art of other eras or civilizations.

It is clear that insignia,i

But even an abstraction on such an item, something that adorned the sovereign’s forehead, must have had some meaning. Perhaps it is as Jantzen somewhat melodramatically yet masterfully interpreted it, that the unity of the apostles around Christ should have moved the hearts of those subjugated by the Ottonians to unite under the banner of a single Christian power. In any case, in the 1190s, German poet Walther von der Vogelweide understood its meaning in a similar way, writing a poem in honor of the newly crowned Philip of Swabia:

The Crown is older than King Philip is,

But you can gaze upon a miracle in it,

How perfectly the goldsmith made it fit.

His kingly head so well suited it

That none could ever rightly separate the two.

Neither does not respect the other.

The two of them now smile upon each other,

The noble stone, that young and generous man.

The sumptuous sight of them delights the princes’ eyes.

Whoever wonders who the rightful emperor is,

Let them behold upon whose head the orphan jewel is set.

The stone is every prince’s guiding-star.

In the original text, there is mention of the Sage (der weise), a specific stone named for its beauty and size, however this detail eluded translation (by V. Mikushevich into Russian). It decorated the back of the king’s head (ob sîme nacke stê), which explains why it served as a ‘guiding star’ (leitesterne) for any prince following his sovereign. It should be noted that the poem by the talented Minnesang served as a political manifesto for the court and did not only reflect the personal opinion of the court poet.

The word ‘symbol’ is very close in meaning to the ‘sign’, but during the Middle Ages, the use of the latter term, ‘signum’, was preferred. Simple objects or gestures take on new meaning, depending primarily on those who use them and secondarily on the imagination of those who observe their use. In works of art throughout most of the Middle Ages, the figure of man is devoid of individual traits, but it always expresses some will or gesture and is always as meaningful. It can even be referred to as an embodied gesture, if a gesture is widely understood.

Every communicative situation in the Middle Ages is ambivalent and can often be construed by contemporaries through two or more contradictory senses—ambivalence and symbol. The cross, while not exclusive to Christians, is the richest symbol in Christianity in terms of content. Depending on the context, the interpreter, the manner of use, the timing, and the reason for interpretation, it can signify ideas and values that are diametrically opposed. It is no coincidence that the cross (Chrismon) appears in a dream that Constantine I3

Chrisme. A marble sarcophagus from the 4th century AD. Vatican Museum, Italy / Wikimedia Commons

It is no surprise that such a miraculous banner, if we are to believe the biographer, was chosen to decorate the ceiling of the throne room of the Imperial Palace in New Rome.

The Savior died on the cross, but according to Christians, his death gave mankind eternal life and salvation, and therefore the symbol of death is paradoxically also the symbol of life. This transformation was expressed in an image, popular in the later Middle Ages,i

A mosaic decorating the conch of the apse in the Roman Basilica of San Clemente, created around the year 1125, depicts the Savior crucified in paradise rather than Calvary.5

The Tree of Life. Mosaic in the apse of the Basilica of St. Clement. Rome, 12th century / Alamy

The tree is surrounded by magnificent floral ornaments depicting the pastures of heaven, where there is a place for all of God’s creatures, evangelists, saints, and angels.6

It would have been possible not to write anything or simply replace the figure of Jesus with a 'precious abstraction' such as uncut stones. This practice was often followed by German ‘konungs’ during the first millennium, when they gave so-called votive crosses to monasteries and temples they considered strategically important. Perhaps some of them knew that, according to legend, the same stone-covered cross (crux gemmata) was erected on Golgotha by Constantine and his pious mother, Elena, the same one on which it is believed that the Savior was crucified. In fact, it is not known whether such a richly decorated cross stood over Calvary as early descriptions do not allow us to determine this conclusively, but this is exactly the kind of cross depicted against a background of Jerusalem by mosaicists in the Roman Basilica of Saint Pudentiana at around the year 400.

Transferring the law. Mosaic in the conch of the apse. Basilica of Santa Pudenziana. Rome, 5th century (restored in the 16th century) / Alamy

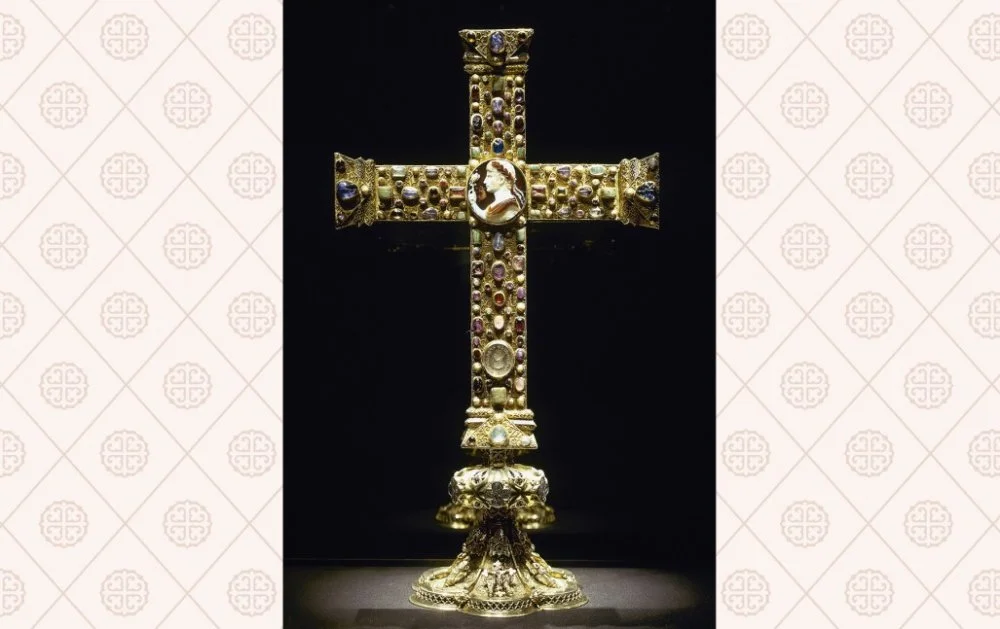

The gift of a cross or other relics and treasures was the most important policy lever for emperors, as well as the barbarian kings that emulated them. The very presence of such a gift on an altar guaranteed, in the present moment, the unseen presence of a distant Basileus or a king or duke eternally traveling his domain. Thus, symbolically the church was turned into a scale model of heavenly Jerusalem, a kind of votive body that was ideologically much more important than a palace. Around the year 1000, Otto III gave a luxurious cross to the Aachen Chapel. On the front of the cross where the Savior is usually depicted, we instead find a remarkable gemma with the image of Octavian,10

Cross of Lothair, votive cross of Otto III. c. 1000. Aachen, cathedral treasury / Alamy

An image of the dead Savior is engraved on the back. During religious processions, the cross was carried ahead of the ruler, which meant that he had to look at the reverse side. Such a peculiar cross, located in the symbolic capital of the state at the sovereign’s will, in the most sacred place clearly demonstrated to the people and to God that ‘Renovatio imperii Romanorum’ (renewal of the empire of the Romans) came together organically in the heart and mind of this devout young emperor with ‘imitatio Christi’ (the imitation of Christ), pax Romana with pax Christiana.

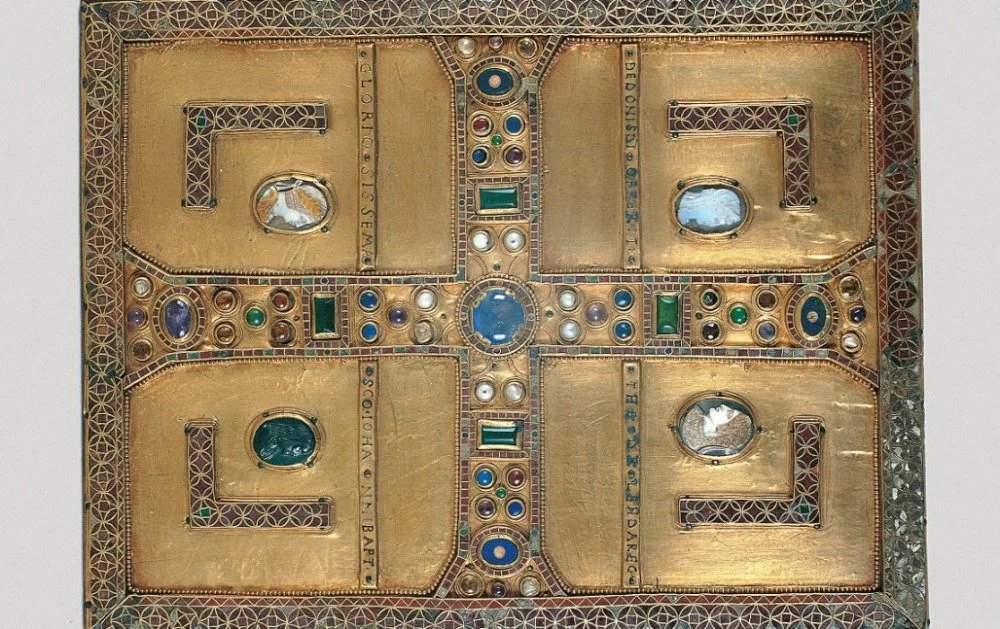

Cover of the "Gospel of Queen Theodelinda". Rome, c. 600. Monza, Treasury / Photo by Paolo e Federico Manusardi/Electa/Mondadori Portfolio via Getty Images

Queen Theodelinda of Lombardy, having accepted the Roman faith around the year 600, received a gospel as a gift from Gregory the Great, which was contained within a case that was decorated with precious stones and organically combined with highly prized enamel to imitate rubies. The crosses here contain a sacred text in the literal sense of the word, and the eight gemmas (unlike the century of Augustus when times were bleak) around these crosses were intended to be seen as a kind of ‘family tree’, which included the new owner of this treasure as a member of the ‘family’ of Roman emperors, popes, and Christ himself.