Fun at the Mahane Yehuda market. Jerusalem, Israel. 2017 /Alamy

Qalam is particularly interested in contact zones of different cultures. This certainly includes Israel, a space of continuous civilisational exchange. Its most notable outcome in popular music has been the Mizrahi style. Like American hip-hop, it has risen from dirt to princes, from the ghetto to the stadiums. The music critic Lev Gankin told us about mizrahi in detail.

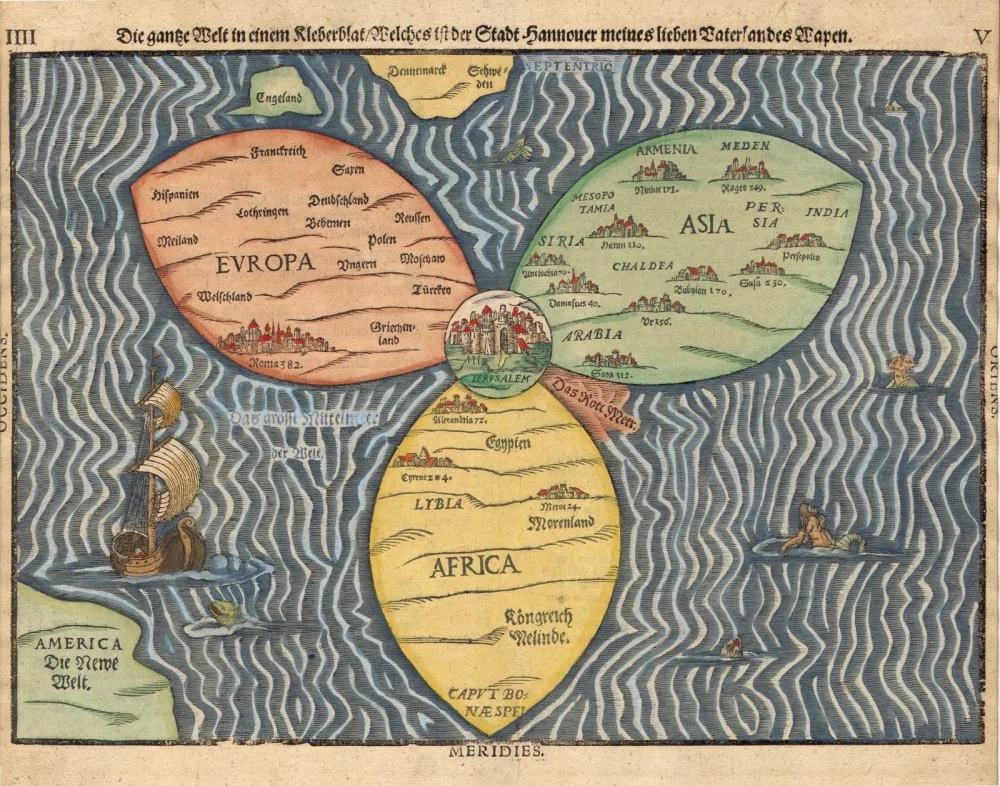

In the second half of the sixteenth century, the Protestant priest and theologian Heinrich Bünting created a geographical map depicting the world in the form of a trefoil: Europe, Asia, and Africa as the symmetrical petals of a flower, with their bases converging at a single point—Jerusalem. Despite, to put it mildly, complicated relations between Jews and Christians, this image is still shown to children in Israeli schools today—thus, a narrative in which the capital of Israel is the center of the universe, the point to which all paths lead, proves to be more powerful than dogmatic disputes. This is not surprising, because at the core of the Israeli state itself lies the same, essential, centripetal force. In the late nineteenth century, the modern aliyah movement was launched, relocating (literally ‘ascending’) Jews, who were previously scattered around the world, to their historical homeland. It continues to this day: according to the Law of Return, tens of thousands of new immigrants from various regions become Israeli citizens every year, from Western Europe to Latin America, and from the former Soviet Union to Ethiopia.

Heinrich Bunting clover leaf map 1581/Wikimedia Commons

These immigrants all arrived, and continue to arrive, not empty-handed, at least in the metaphorical sense. Each person carries with them a set of traditions and customs from their country of origin, and these immediately begin interacting with each other in new conditions. Hence the inherently hybrid, composite nature of Israeli culture, including its music. The country's territory, a mere 22,000 square kilometers, has remained a space of continuous cultural exchange throughout the seventy-five years of its existence: friendly and violent, equal and abusive. In popular music, one of the most noticeable results of this exchange has been the Mizrahi style—a distinctly Israeli phenomenon with a history that remotely resembles the life path of American hip-hop: from the mud to the throne, from the ghetto to the stadium, from the periphery of show business to its very center. Today, Mizrahi music is, in fact, the Israeli musical mainstream: any radio hit either is entirely in this style or uses at least some of its elements, and for two decades in a row, arguably the country's best and most popular singer has been Mizrahi artist Eyal Golan.

The paradoxes of Mizrahi music begin quite literally at its threshold, starting with the name itself. ‘Mizrah’ in Hebrew translates to ‘east’, but here, the cardinal directions were interpreted as roughly as they were on Henry Bunting's trefoil map. In the 1950s, the term ‘Mizrahim’ began to refer to Jews arriving in Israel who were not from Europe, in contrast to the Ashkenazi who were at the helm of the young state: immigrants from Russia, Poland, and Germany.

Immigrants from places like Iraq, Yemen, Egypt, and Morocco were broadly categorized as Eastern Jews, even though, for example, Morocco is located much farther west than Israel itself.

This superficial and geographically imprecise generalization transparently hinted at the less-than-warm feelings of the Ashkenazi elite towards the Mizrahim. Journalist Aryeh Gelblum of the newspaper Haaretz wrote in 1949: ‘These are very primitive people, their level of education borders on complete ignorance, they adapt poorly to life in Israel, are chronically lazy, and cannot stand to work.’ Here's another paradox: while proclaiming the new state as a homeland for all Jews, its creators still divided its inhabitants into strata: the privileged and the not-so-privileged. When Eastern Jews arrived in Israel, they often ended up in transit camps, called ‘Ma’abarot’ in Hebrew. After that, they most often went to live in so-called ‘development towns’—from Kiryat Shmona in the north to Sderot and Netivot in the south. At the time, these could only be called cities in a conditional sense; they were more like hastily constructed outposts on the periphery of the country, serving as visible evidence of Israeli territorial control. Of the 170 such settlements that had arisen by the end of the 1950s, 120 were populated by immigrants from the Middle East and North Africa.

The ghettoization of Mizrahi Jews extended to their culture: among the ‘Eastern’ immigrants of the 1950s, there were musicians, some of them with glorious careers in their countries of origin. However, none of them truly managed to break into the Israeli market. Some, like the singer Zohra Al Fassiya, fell into obscurity. The superstar of North African music, who had once performed at the court of the king of Morocco, couldn't integrate into the cultural reality of her new country and ended her days in poverty and loneliness. The fate of the Kuwaiti brothers Daoud and Saleh Al-Kuwaity played out similarly: the authors and performers of hundreds of compositions that had become musical standards in Iraq and Kuwait immigrated to Israel in 1951 and, until their deaths, were forced to survive by selling off their household goods. The disappointment of the Al-Kuwaity brothers was so great that both forbade their descendants from pursuing music.

A couple of individuals were somewhat luckier: Egyptian Filfel El-Masri and Moroccan Jo Amar. Both released several notable and successful records in Israel, although these were primarily distributed only among their own communities. The key hits of each artist tell the story of the difficulties of adapting to their new reality. For instance, El-Masri's song ‘Hakol Betashlumim’ (‘Everything Is Paid in Installments’, 1959) is dedicated to a practice unfamiliar to him but extremely popular in his new country: the concept of buying on credit, where any payment, including groceries in a supermarket, can be divided into several periodic installments. This easily leads to accumulating debt, which the wife of the song's narrator astutely exploits, causing him to tear his hair out in frustration.

Even more expressive is Jo Amar's work titled ‘Lishkat Avoda’ (‘Employment Office’, 1959): in it, the author describes first his misadventures in the Ma’abarot transit camps and then his experience of trying to find work. The clerk at the labor exchange asks where he came from, and upon hearing the word ‘Morocco,’ promptly kicks him out. However, our hero, not being a fool, returns the next day, introduces himself as a Pole, and receives a polite, even obsequious ‘Please come in!’

Part of the song ‘Lishkat Avoda’ is performed in Arabic. This common practice was one of the reasons why the Israeli elite initially stigmatized Mizrahi culture as low and primitive. The State of Israel was declared amid the War of Independence (1948–1949) and remained in a state of conflict with the surrounding Arab countries for most of its history. In this context, Arab and Middle Eastern culture was mainly seen as the culture of the enemy and was marked accordingly in public discourse (following a principle more recently immortalized in a symmetric meme that has been circulating on the internet: ‘our blessed homeland—their barbarous waste; our glorious leader—their wicked despot’ and so on).

There were exceptions to this rule: for instance, special consideration was given to the work of Yemenite Jews, which, although also distinctly oriental, held indisputable historical authority (in Israel, it was believed that this ethnic group, which had not left the Middle East region for many centuries, preserved the millennia-old traditions of the Jewish people in a form closest to the original). Thus, Yemenite musicians had more opportunities to showcase their talent in the country. The first to do so, back in the 1930s, was the singer Bracha Zefira, followed by others like Shoshana Damari, a true superstar of the official Israeli musical mainstream of the century, who performed the composition ‘Kalaniyot’ (‘Anemones’, 1948), which would certainly find its place in, if such a corpus were to be compiled akin to the American model, the Great Israeli Songbook.

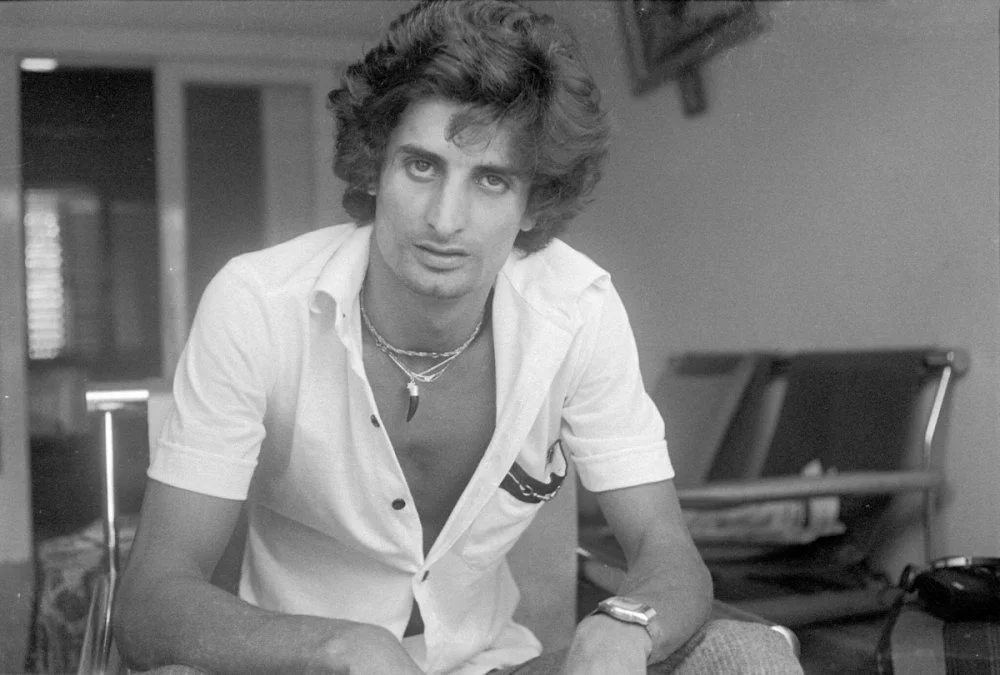

Jo Amar at a concert/National Library of Israel

The songs of both Filfel El-Masri and Jo Amar were the work of Ashkenazi composers, in their familiar, Europeanized style, with only occasional, light Oriental influences. Nonetheless, the music of the two singers sounded fundamentally different from other music of the time. It wasn't just the Arabic language, which was only episodically used in their songs. Even the Hebrew they used was distinct, with pronounced guttural sounds like ‘het’ and ‘ayin’, unlike the smoother speech of European Jews. The instrumentation was also different, featuring instruments like the oud, kanun, darbuka, and later the Greek bouzouki and Turkish baglama. The harmonic basis of their compositions was often Eastern makams, most commonly bayati or kurd; the music ventured beyond the confines of equal-tempered tuning and made extensive use of quarter tones. The singers' voices had a nasal quality, and on long notes, they would often embark on fascinating melismatic journeys through the musical scale—in the Israeli tradition, this technique became known as ‘silsulim’ (curls, ornaments, or, in a narrow musical sense, trills).

From the perspective of the prevailing Westernized style, all of this sounded quite exotic and reinforced the idea of Mizrahi Jews as suspicious, overly ‘Arabized’ foreigners. For the Mizrahim themselves, however, this was their tradition, imbibed almost literally with their mother's milk. For centuries, these repatriates from Asia and Africa had coexisted quite harmoniously with ethnic Arabs in their countries of origin. ‘The horror is that we risk being absorbed by them, rather than the other way around,’ Aryeh Gelblum continued in the quoted article. To avoid this alarming scenario, Eastern Jews were subjected to ‘Israeliization’ and ‘de-Arabization.’ In exchange for civil rights and the opportunity to live in the national Jewish state, effectively forming its proletariat, they were asked to discard their ‘Eastern’ identity. In Hebrew, a language traditionally tolerant of new word formations, a special verb emerged: ‘lehishetaknez’, meaning ‘to Ashkenazify’ or ‘to become culturally Ashkenazi’.

Alfred Dehodencq. Jewish festival in Tetuan 1865.

This partially worked, as many representatives of the next generation of Mizrahi Jews, born in Israel, preferred to express themselves in different musical spaces, such as rock music. The Tel Aviv-based band the Churchills, authors of one of the first Israeli rock albums, composed music that hardly revealed the origins of its creators. Even the piquant mandolin solos (as in the song ‘Subsequent Finale’) were closer to the orientalist experiments of psychedelic rockers from England and the United States than to the authentic Eastern styles on which the musicians' ancestors had been raised. The music of their parents was often not well regarded by the artists of this circle. As Yehudit Ravitz, another successful Israeli singer-songwriter of the time, recalled, ‘As a child, I begged my mom not to play her Arabic music when my friends came over, so as not to give them a reason to mimic the whiny voice of the famous Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum. My mom liked her singing; it reminded her of her childhood in Egypt. Folk music, which my father used to listen to, was always much closer to me. He came from Poland and knew all the old Zionist songs, even those that were composed in Europe.’

Growing up in Be'er Sheva in the south of Israel, Ravitz gained fame in 1977 by performing the richly orchestrated romance ‘Slichot’ (‘Forgiveness’) at the official Israeli song festival, with lyrics based on the poetry of Lea Goldberg. This was followed by participation in the recording of a children's album called Ha-Keves Ha-Shisha-Asar (The Sixteenth Lamb) with the Ashkenazi rock elite and a successful solo career in the Israeli mainstream.

The Churchills achieved a certain level of success in their attempts at cultural assimilation: they accompanied Arik Einstein, the pioneering Israeli singer and songwriter, on his best albums, and guitarist Yitzhak Klepter was part of the golden lineup of the most popular Israeli rock band of the 1970s, Kaveret (‘Hive’). However, a prerequisite for this success was the near-complete erasure of their roots, not only on a stylistic level but also on a personal level. In their efforts to become part of the refined Israeli mainstream, the Mizrahi musicians inevitably distanced themselves from the community that raised them. For a time, the Churchills' headquarters were not even in Tel Aviv, but in London, where they released two strong English-language albums under the titles Jericho Jones and Jericho. Years later, Yehudit Ravitz apologized to her mother for being ashamed of her background and her favorite songs.

Through all this, the wider Mizrahi community carried on with its own distinct culture, including a musical tradition closely tied to its Middle Eastern heritage, while the attitudes of the cultural elite towards it remained dismissive. In 1975, Nissim Sarussi, a singer of Tunisian origin known for sentimental ballads like ‘Eyni Yakhol’ (‘I Can't’) and ‘Ima’ (‘Mom’), was suddenly invited to Yaron London's talk show, only to be humiliated on live television by the host. London called Mizrahi music tasteless and suggested that only in Israel could a person who looked and sang like Sarussi hope to become a popular artist.

Parallelly, however, tectonic shifts were taking place in Israeli society, primarily linked to the Yom Kippur War of 1973, during which Israel lost over 2,500 soldiers (with approximately 8,000 more sustaining various degrees of injuries). For a small country, these were staggering numbers. A significant percentage of the casualties were Mizrahi Jews, among whom a question began to arise: Why, when it comes to sacrifice for Israel, is it for us (Mizrahi Jews) to step up, but when it comes to governing the country, we are expected to stay quiet?

Eastern Jews began to consider the possibility of proper political representation. In 1977, their votes undermined the hegemony of the left-wing forces that had been in control of the country since its establishment, leading to the rise of the right-wing Likud party. ‘Immediately after the elections, this was seen as an example of protest voting by the marginalized Mizrahi population against the dominant socialist establishment, composed almost entirely of Ashkenazi Jews,’ wrote Dov Waxman. ‘But the fact that the Mizrahi voted for Likud in all subsequent elections indicates that the reason ran deeper. The way the party (especially its leader Menachem Begin) emphasized Jewishness and Jewish traditions appealed to Mizrahi Jews, as this idea allowed them to integrate into Israeli society on an equal basis. By voting for Likud, they demonstrated their desire to be a full part of the Israeli nation.’

Following the Yom Kippur War, Ahuva Ozeri, a singer hailing from a Yemeni Jewish family, who played the bulbul tarang (an Indian string-plucked instrument) as accompaniment, composed a poignant song titled ‘Hechan Hachayal?’ (‘Where Is the Soldier?’). It was a rare Mizrahi music performance on a relevant socio-political issue, dedicated to a young man who had lost his life in battle, the son of her neighbor. Nonetheless, an incident that appeared unrelated to warfare but holding significant importance for the scene's evolution played a more pivotal role in the more significant changes that were to come.

Ahuva Ozeri/photo by Ilan-Beskor

In 1973, Asher Reuveni was preparing to get married. Together with his brothers, he owned a small electronics store in Tel Aviv’s Htikva Quarter, predominantly populated by Yemeni immigrants. Unfortunately, the wedding celebrations were marred by sad news: his bride's brother would not be returning from the war. After several months of mourning, the friends of the newlyweds finally decided to throw them a joyful party (referred to in the Mizrahi community as a hafla), for which they invited the musicians Yosef Levy, better known as Daklon, and Moshe ben-Moshe, both of whom would eventually find fame as members of an important ensemble in the Mizrahi movement: Tslilei Ha-Kerem (‘Sounds of the Vineyard’, with the vineyard referring to the Kerem Ha-Taymanim neighborhood where the musicians grew up).

The situation itself was not out of the ordinary—most Mizrahi artists earned their livelihood by performing at weddings and bar mitzvahs. The Churchills, with their performances in prestigious academic halls, accompanied by a symphonic orchestra conducted by the great conductor Zubin Mehta, were something of an outlier. The favored venues for other Eastern Jewish musicians at the time included private apartments, restaurants, and even local gas stations with hastily assembled stages.

The hafla of the Reuveni couple continued until the early morning, with more than 200 guests coming to congratulate the newlyweds. However, friends who were still in the army couldn’t attend, and so, the groom and his brothers decided to record the party on cassette, with a small, inexpensive tape recorder running in a corner all night.

Later, this cassette grew to be mythologized in the history of Eastern Jewish music, as a kind of seed from which the entire corresponding culture grew. While this may be an exaggeration, the Mizrahi music industry did indeed have its roots in the recording of Asher Reuveni's wedding. Although the background noise of the guests often drowned out the music itself, the popularity of this recording quickly made it apparent that the target audience wanted to listen to their favorite songs not only live but also in recordings. People who didn't personally know the newlyweds began offering 100 lira for a copy of the cassette (the new Israeli shekels were introduced later, in 1980). The Reuveni brothers realized that they could make a good profit from this, so they founded a record label and a production center that went on to become a powerhouse of Mizrahi music.

The band Teapacks perform on stage during a rehearsal for the Eurovision semi-final. 9 May 2007. Helsinki, Finland/Getty Images

Another stronghold of this music was the Tel Aviv bus station, a major transportation and trading hub. Amidst the stalls selling clothes, used goods, and various snacks, numerous cassette vendors now appeared, offering counterfeit products, among others. ‘For ten lira, you could get three cassettes,’ recalled Kobi Oz, the frontman of the band Teapacks, which straddled the line between alternative rock and Mizrahi music in the mid-1990s. ‘I would go to the old station, and it was like entering another country for me: a country of suspended reality, whether it was raining or the sun was shining.’ Teapacks originated in Sderot, a southern ‘development town’ on the border with the Gaza Strip. Young Oz, like many other Mizrahi Jews, regularly found himself at the Tel Aviv bus station, buying fresh cassettes and taking them home. Thanks to this alternative grassroots cassette infrastructure, Mizrahi music's melodies and rhythms spread rapidly throughout the country. Mainstream media—radio, television, and major record labels releasing vinyl records—continued to ignore what was happening right under their noses, but it no longer mattered.

There was another paradox inherent to this cultural phenomenon: in Europe and the USA, the audio cassette, a cheap and user-friendly medium, became a symbol of the musical underground, enabling cutting-edge, experimental artists who didn't rely on record deals to disseminate their work among a small, dedicated community and preserve it for posterity. Israel, too, developed its own ‘cassette underground’, but it featured a completely different sound: not like the avant-garde experiments of the West, but democratic, entertaining, and friendly music meant for the widest possible audience. ‘My goal is to sing songs that touch people,’ said Zohar Argov, a key figure in Mizrahi music in the 1980s. ‘I notice that the Israeli audience is quite sentimental. They love songs that reach the heart.’

A descendant of Yemeni immigrants, with a memorably Middle Eastern appearance, strong stage charisma, and powerful vocal abilities, Argov became a star in the Mizrahi community with the release of his first single, ‘Elinor’, in 1980. Two years later, he triumphed at the Mizrahi Singer Festival in Jerusalem, with victory going to his composition ‘Haperakh Begani’ (‘The Flower in My Garden’). More important than the prize was the fact that the 1982 festival was televised nationally for the first time. As a result, the track reached not only members of the artist's own community but also those who hadn't had access to such music before—they heard it and loved it, as a result of which it became the first Mizrahi-style song in history to make it onto the Israeli radio broadcasters' year-end list, claiming an honorable fourth place.

Zohar Argov at the mizrahi festival 1985/Nati Harnik/GPO

Comparing classic recordings by Zohar Argov with early examples of Mizrahi music performed by artists like Jo Amar and Filfel El-Masri, they are unmistakable as part of the same cultural continuum, in spite of some clear differences. Motti Regev and Edwin Seroussi, in their book Popular Music and National Culture in Israel, highlight seven distinct features (musical codes) of Mizrahi music during its heyday.

Some of these elements are present in the song ‘Lishkat Avoda’: static harmony, a cyclical pattern in the rhythm section, vocal melismatics, and reliance on Eastern makams (guitarist Yehuda Keisar, who collaborated extensively with Argov, even constructed a special guitar with quarter-tone frets in the 1970s). However, there are also other features, primarily related to instruments or form, that became characteristic of Eastern Jewish music only in its new and, one might say, peak phase. Jo Amar didn't use electric rock instruments, but for Argov and his contemporaries, these became an integral part of the arrangement, alongside the kanun and darbuka. The early songs about employment bureaus and the payment of dues didn't always fall into even segments of eight or sixteen beats, and they even avoided a rigid verse-chorus structure, while ‘Haperakh Begani’, on the contrary, was structured in precisely this way. ‘With regard to its musical structure, Mizrahi popular music is undoubtedly Western music,’ wrote Avi Picard. ‘The new style is based on studio technology and sound recording distribution. Its foundation is a written score that allows for the precise repetition of musical sections, rather than a unique, live performance.’

Instead of the elaborate improvisations and interconnected musical fragments that were characteristic of Jewish musical traditions from Muslim countries, this piece is a self-contained song lasting about three minutes.

Of course, in part, this evolution was driven by purely practical reasons: Jo Amar didn't have access to electric guitars, while Zohar Argov did. However, this explanation is incomplete. The music of the Mizrahi people in the 1950s was a scattered collection of repatriate traditions, and the term ‘Mizrahim’ was often a derogatory generalization, used by the elite to define the ‘other’ and distance themselves from it. However, by the 1980s, the word described the specific identity of the descendants of repatriates from Muslim countries in Asia and Africa: the Mizrahi generation born in Israel saw itself as a distinct sociocultural group. The songs of Zohar Argov, his contemporaries, and his followers were no longer transplanted Moroccan, Iraqi, or Yemeni music; they were fundamentally Mizrahi music, articulating the aspirations of a specific segment of Israeli society.

Zohar Argov / Moshe Shai/FLASH90

This music inevitably blended all the sounds that the Mizrahi people loved and listened to. One example was the Greek chanson in the style of the popular Israeli singer Aris San. Argov's ‘Elinor’ was, in fact, a cover of a Greek composition, and Yehuda Keisar mastered a staccato guitar style that imitated the sound of the Greek bouzouki. Another influence was Turkish Arabesque music: the famous hit ‘Tipat Mazal’ by the Mizrahi singer Zehava Ben was based on a song by the mustachioed heartthrob Orhan Gencebay (there was no copyright agreement between Israel and Turkey in 1990, so melodies from Turkish chanson could be borrowed freely). Arab vocalizations, as heard in the intro to ‘Haperakh Begani’, used the technique called melisma, which involved prolonged, multi-note singing of a single syllable.

In this later Mizrahi music, you can also find the passionate romance of Sanremo, the electrifying energy of rock and roll, brass arrangements of Balkan and other Eastern European origin (the arranger of ‘Haperakh Begani’, Nancy Brandes, was originally from Romania), and sometimes even official Ashkenazi chanson. Haim Moshe, a popular Mizrahi singer in the 1980s, commissioned new compositions from Naomi Shemer, the composer of ‘Jerusalem of Gold’, and dozens of other songs from the Great Israeli Songbook. This was an Ashkenazi–Mizrahi collaboration that was not considered inappropriate by that point in time, clearly signifying a paradigm shift, as does the fact that poet-songwriter Meir Ariel, a veteran of the Six-Day War, often informally referred to as the Israeli Bob Dylan, included a cover version of Zohar Argov's song ‘Kvar Avru Shanim’ (‘Years Have Passed’) in his repertoire.

During the 1980s, Mizrahi music still rarely appeared on prime-time TV, but at least it was no longer scorned there, as had happened to the unfortunate Nissim Sarussi. On the contrary, Eastern Jewish singers reclaimed the derogatory nicknames that Ashkenazi Jews had labeled them with, such as ‘chachach’ or ‘frecha’ (meaning ‘chick’). ‘Shir Hafrecha’ (‘The Chick Song’, 1979) became Ofra Haza’s, an artist of Yemeni origin, first hit, although she was only tangentially connected to the Mizrahi scene.

Sephardic synagogue chants, or ‘piyyut’, also contributed to this musical blend. These chants were often based on melodies from secular Jewish and Arab music. Zohar Argov, for example, sang in the synagogue from a young age. The lyrics of his songs were often written in lofty, old-fashioned language. For example, ‘You were the apple of my eye day and night; you were an angel of God in the darkness’, as sung in ‘Haperakh Begani’. As Ben Shalev noted, the composition was ‘written in a language that resembles the “Song of Songs” (King Solomon), more than Hebrew typical of Israeli pop music’. Mizrahi Jews, on average, were more religious than the European Zionists who were foundational to the establishment of the state. (Eventually, the ultra-orthodox party Shas emerged as their political representative.) This religiosity often went hand in hand with ideological conservatism. The parents of the Israeli superstar Sarit Hadad did not consider a pop music career appropriate for their daughter—she had to secretly perform in clubs, where she was eventually noticed by producers.

With the names of Hadad, Zehava Ben, Eyal Golan, and other newcomers in the 1990s, Mizrahi music transitioned into a new era, at least commercially. Unlike Zohar Argov, who didn't live to see the new decade, these three, in particular, could be called crossover artists: not only did they not shy away from cross-genre experiments, but, on the contrary, they bet on them. In 1992, Ben appeared at the microphone with a cover of ‘Kiturne Masala’ (‘When Luck Returns’, with mixed languages) by the popular electropop group Ethnix; her melismas were a striking contrast to the more straightforward rock vocal of the group's leader, Zeev Nehama. In 1997, Ethnix initiated the first of several collaborations with Golan, and the previously mentioned band Teapacks invited Sarit Hadad to record the song ‘Lama Alacht Mimenu’ (‘Why Have You Left Us’). Mizrahi music thus directly interacted with the mainstream, but remarkably, it avoided ‘Ashkenazification’. Through these joint recordings, it was Golan and Hadad’s musical style, rather than their individual presence as musical personalities, that was accepted into the mainstream—all while still maintaining their distinctive sound.

The musicians of Ethnix and Teapacks needed Mizrahi singers specifically in their professional capacity—as bearers of a characteristic vocal style. This phenomenon was repeated in the 2000s, when Israeli rappers turned to them. Some, like the popular Jerusalem-based hip-hop collective Hadag Nahash (The Fish-Snake), demanded specific skills from Mizrahi instrumentalists. Their song ‘Shir Nehama’ (‘Comfort Song’, 2010), for example, uses the Greek-style electric guitar made recognizable by Yehuda Keisar. Dr Oded Erez notes that the sound resembles a sample from an old record, the foundation of countless hip-hop tracks, except that in Hadag Nahash's case, it was played live. As for the Mizrahi vocalists, they obviously played a role parallel to that of R&B singers in American hip-hop, with their melodic singing serving as a melodic counterpoint to the rappers’ verses. The most successful Israeli pop duo of the 2010s and 2020s, Static & Ben El Tavori, utilize this very dynamic: an emcee (Static, also known as Liraz Russo) and a Mizrahi singer (Ben El Tavori).

The history of Mizrahi music from the late 1990s to the present is a chronicle of continuous and extensive development on multiple levels at once: sound, media, politics, and meaning. ‘As a friend of mine, a Jerusalem sound man, put it: In 2015, it isn’t accurate to say that Mizrahi is a sub-genre of Israeli pop, or even a successful genre, or that it threatens the mainstream,’ wrote Matti Friedman in an article titled ‘Israel’s Happiness Revolution’, named after a Mizrahi song by Lior Narkis and Omer Adam. ‘It is the mainstream. It is Israeli pop. If you put a stethoscope to the country’s chest right now, the rhythm you’d hear would be Mizrahi.’

Expanding further, past rock and hip-hop, Mizrahi music was also able to seamlessly marry the oriental melodic profile and vocal ornamentation to a globalist club-electronic pop sound, from EDM to trap and reggaeton. ‘What appeals to Israelis is bass and silsulim!’ proclaimed Static & Ben El Tavori in their breakthrough hit ‘Silsulim’ (2016). Judging by the 59 million views on the song’s YouTube video, they knew what they were talking about. Mizrahi music has thrived not only in new media, but also in the old media such as radio and television. The style has long dominated Israeli vocal competitions, and Eyal Golan even had his own personal TV show searching for young talent. In 2008, Golan packed the Caesarea Amphitheater, the country's most prestigious concert venue, previously associated with only ‘respectable’ Israeli pop and rock artists like Shlomo Artzi.

Tel Aviv, bus stop, 2016/Shutterstock

Of course, this situation does not suit everyone. In 1992, Jonathan Geffen, a prominent representative of the ‘old’ Ashkenazi cultural elite, wrote a column in the Maariv newspaper, ‘The Turks Have Taken Over Tel Aviv!’ The apparent provocation was the Turkish melodies of Zehava Ben's song ‘Tipat Mazal’ and a few others. ‘I thought we had conquered Tulkarm [a Palestinian city on the West Bank], not that Tulkarm had conquered us,’ said politician Jair Lapid ten years later, after hearing a song by Mizrahi artist Amir Benayoun on the radio. For Geffen and Lapid, Mizrahi music obviously remained a marker of a foreign, even hostile, culture. In reality though, it has worked more like soft power, building bridges where other actors in Israeli political and cultural life prefer to burn them. Zeheva Ben, for example, successfully performed in Egypt, Jordan, Jericho, and Nablus for as long as it was possible, and her cassette recordings could be found in industrial quantities in the 1990s, not only at the Tel Aviv bus station or the Machane Yehuda Market in Jerusalem, but also in street markets in neighboring Arab countries and even in the territories of the Palestinian Authority.

The contemporary Mizrahi mainstream must often reconcile seeming contradictions. The music remains deeply religious—an obligatory element of the concerts of the hitmaker Omer Adam, a practicing Jew who consistently refuses to perform on the Sabbath, is the ballad ‘Modeh Ani’ (‘I Give Thanks’, 2015), based on the text of the morning prayer. At the same time, an equally obligatory element of his performances is the carefree and slang-laden gay anthem ‘Tel Aviv’ (2013). However, according to Dr Oded Erez, these apparent contradictions might more accurately be seen as an attempt to broadly outline the contours of the modern Israeli middle class, largely composed of Mizrahi Jews and encompassing diverse trends: Eastern queerness, religious traditionalism, and hedonistic hyper-masculinity.

Omer Adam and Yael Shelbia/Instagram@omeradam

It's interesting to note that Omer Adam, strictly speaking, is not Mizrahi, or at least not entirely so: his mother is Ashkenazi and his father is a Mountain (Caucasian) Jew. Adam himself was born and raised in the United States. However, in its current mainstream form, Mizrahi music is no longer the exclusive domain of specific sub-ethnic groups; it has evolved into a cosmopolitan sound with a certain (and fairly broad) set of distinctive characteristics. The song ‘Silsulim’ exemplifies this, showcasing the characteristics of the style but also blending seamlessly into a lineup of global summer beach dance-pop hits such as ‘Despacito’.

In recent years, an alternative stratum has been taking shape within the community, represented by those who seek to return the Mizrahi style to its roots, both literally and figuratively. Jerusalem-based singer Neta Elkayam is reintroducing the world to the music of Zohra Al Fassiya, a Moroccan star from the mid-twentieth century, whose illustrious career effectively came to an end with her repatriation to Israel. The Haim sisters, who grew up in the southern desert of Israel (unrelated to the American band HAIM, also, by a strange coincidence, consisting of three sisters), delve into their own family history through their music. As part of the A-WA project, they revive the oral musical tradition of Yemenite Jews (or perhaps more precisely, Jewesses). ‘While men went to the synagogue and sang religious songs there, women stayed at home and had closer interactions with the Arab community,’ explains one of the sisters, who holds a bachelor's degree in ethnomusicology. Unsurprisingly, the songs of A-WA are performed not in Hebrew but in the Yemeni dialect of the Arabic language.

Dudu Tassa, the grandson of Daoud Al-Kuwaity, one of the Iraqi Jewish brothers mentioned earlier, who created a body of musical standards in their country of origin, ignored his grandfather's prohibition and became a musician. Among his many genre-spanning projects, the standout is the ‘cross-cultural Jewish–Arab project’ Dudu Tassa & the Kuwaitis. In this ensemble, the artist, along with instrumentalists from Israel and Iraq, offers modernized versions of the music of his ancestors. The group performed in the USA at the Coachella Festival and embarked on a full tour as the opening act for Radiohead in 2017. Tassa’s latest album, Jarak Qaribak (2023), is also dedicated to the Middle Eastern musical tradition, but this time, a non-Jewish one. Tassa recorded the album in collaboration with Jonny Greenwood.

Clearly, the history of Mizrahi music, woven through with paradoxes and as intricate as the melodies of Zohar Argov's songs, continues to develop intensely and unpredictably even today. Its core, however, remains in the same place, where the three different-colored petals converged on Heinrich Bünting's geographical map.