In this lecture series, medieval historian Irina Varyash discusses how Muslims ruled Spain for approximately 800 years, transforming it into one of medieval Europe's most developed and prosperous regions. The first lecture focuses on the Arab conquest of Spain and the peak and fall of Islamic al-Andalus.

Try asking for coffee with sugar, starting a discussion on algorithms or studying algebra, buying something made of cotton, or naming the caliber of something in any European language, and you cannot avoid Arabisms. Europeans acquired these words, of various origins, from the Arabic language a long time ago, in the Middle Ages. The Spanish language has one of the highest number of Arabisms of any European language, accounting for about 10 per cent of its vocabulary. Portuguese and French also include a significant number, and even English and German have some of these words. Unlike contemporary Arabisms that integrated into the vocabulary of Europeans, words borrowed in the Middle Ages have long become "their own", and language speakers do not always know their origins. They have simply been used in everyday life for many centuries.

So, how did it happen that Europeans forgot that they once interacted so closely and peacefully with Arabic-speaking Muslims that they started using Arab words to refer to fruits, pillows, pitchers, positions, and even "luck"?

Modern Western civilization sincerely strives to overcome Eurocentrism, a kind of adolescent complex that originated in the Early Modern period and which received renewed geopolitical momentum in the twentieth century. The very aspiration to and act of trying to overcome this complex naturally indicates its persistence. Even today, we know little about the immense role played by Islamic culture in the formation of Europe as it is now, with its universities, rational philosophy, and tablecloths on tables.

However, the important thing to consider is that we are not accustomed to thinking, or talking about, the Muslims and Christians who lived side by side in Europe. In fact, their experiences, destinies, and knowledge, combined together, should be referred to as "Muslim Europe". Modern ways of thinking lead us to place the Muslim world infinitely far from the European realm on an imaginary world map. However, the truth is that Islam quickly established itself in Europe, which can be easily understood by examining the physical geography of the early Middle Ages.

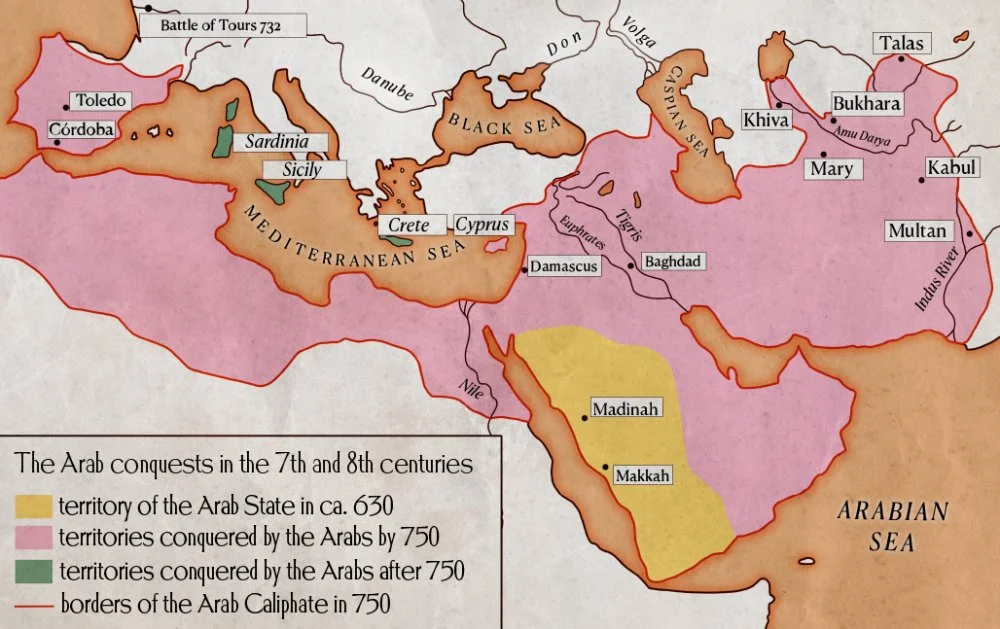

Qalam

Judge for yourselves: it took less than fifty years from the birth of Islam for Muslims to appear at the walls of Constantinople, then in Sicily, after that in Byzantine Africa, and, forty years later, to land in western Europe, on the lands of Spain. By the beginning of the eighth century, they had established a significant state with its capital in Damascus and built a fleet that could rival the Byzantine navy. It should be noted that at that time the civilized space that held fundamental significance for Europeans was not so much Europe itself but the Mediterranean. A large part of this area, by historical accounts, swiftly fell under Muslim control: from Cilicia in the east to the Atlantic and the Pyrenees in the west, and thus European territories were also part of the Islamic state.

The Muslims finally conquered Sicily in the ninth century. From there, they launched raids on southern Italy, reaching Naples and threatening Rome. For two years, the pope in Rome was forced to pay them tribute. In the eleventh century, the Normans established themselves in this area, but the region still maintained close ties with Fatimid Egypt and the Middle East. In addition, in the early eighth century, the Muslims crossed the Straits of Gibraltar, and Spain, which controlled the Iberian Peninsula, the largest one in southern Europe, became home to many Yemenis, Syrians, Iranians, and Berbers for 800 years.

Battle of the Yarmuk. A miniature from a Catalan manuscript. Fourteenth century/gallica.bnf.fr

The rise of Al-Andalus

Various Arabic and Latin chronicles, along with romanceroi

"…The inscription that they saw said:

"You, the King, will face a great misfortune!

Whoever sneaks into this dwelling,

Shall destroy his native land!"

The chest full of riches

Was taken from a hide.

Banners were inside it. And each banner

Depicted hundreds of Moors lifelike,

Their swords unsheathed,

Swift and spirited horses,

Terrifying faces of riders.

Crossbows, catapults—

What an intimidating sight."

—Romancero of King Rodrigo (Translation into Russian by A. Revich and N. Gorskaya)

Other Christians sought the cause of King Rodrigo's defeat in his dishonorable love for the daughter of Count Julian. According to legend, Count Julian, who served as the governor in African lands, was driven by a desire for revenge over his daughter's disgrace, and therefore he aided the Moors in crossing the strait into Spain.

As is often the case, intricately concealed historical events were behind the fictional details and twists of the plot. In the month of Ramadan in the year 91 of the Hijrai

The Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula was accomplished through several short military campaigns and took place over a period of five to six years. By crossing the strait between the continents, the Muslims gained control of the lands of future Andalusia, the central regions of the peninsula, the Levantine coast, and certain areas of Septimania.

Charles de Steuben. Battle of Poitiers, October 732. 1837 / Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images

Only the northern mountainous regions of the peninsula retained their independence, largely because the southern inhabitants had little interest in these cold and infertile territories. The surviving Visigothic aristocracy was the only significant force that sought to resist the newcomers from across the strait. They found refuge in the northern lands of Austrias and from there they began the reconquest of Spain, better known by the name of the Reconquista.i

Eight centuries of Islamic history significantly transformed the political, ethnic, economic, social, and cultural landscape of the western part of Europe. Spain, among other things, became a cultural conduit for the achievements of the Muslim world in the medieval Latin world. Over the course of 800 years, approximately forty generations of inhabitants on the peninsula, Muslims and Christians alike, coexisted as a norm and an integral part of everyday life.

The civilization established by Muslims on the Iberian Peninsula was named al-Andalus, from which the name of one of the southern provinces of modern-day Spain, Andalusia, was derived. Al-Andalus wrote a vibrant and original chapter in the history of medieval Europe. It would be unjust and shortsighted to impoverish the history of Europe by disregarding the Muslim presence and overlooking the Islamic contributions in fields such as science, arts, navigation, agriculture, political governance, social strategies, medicine, and everyday life.

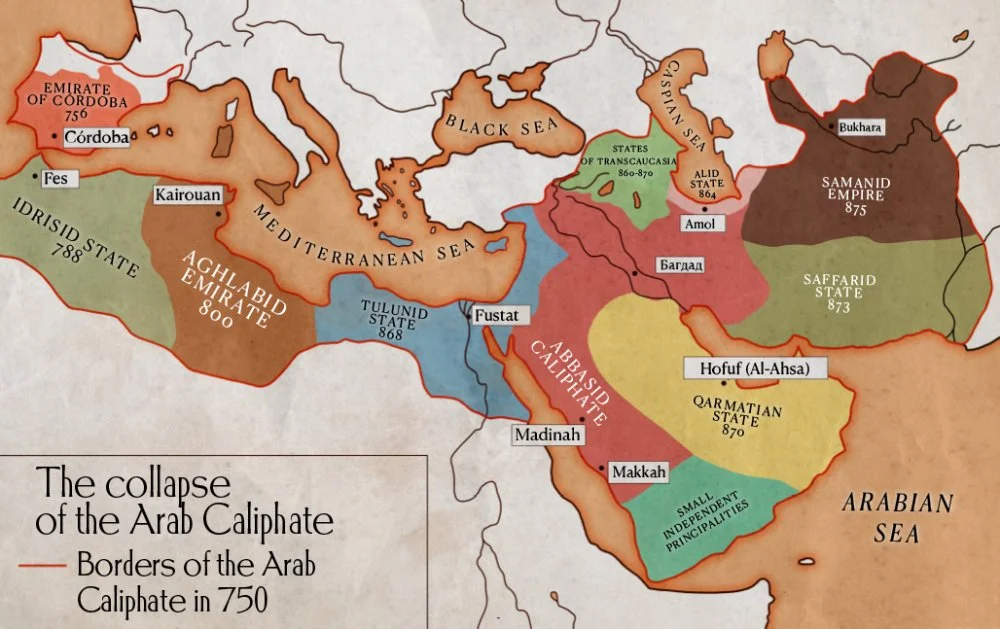

Over the course of eight centuries, the Islamic-Spanish civilization existed within various political entities holding distinct positions on the map of the peninsula. Initially, the expansive Emirate of Cordoba was established, the westernmost province of the Arab Caliphate,i

Certainly, al-Andalus was primarily a part of the Dar al-Islam, the Islamic and Islamicized world. However, its distance from the metropolis had its political advantages and granted freedom in internal Spanish affairs, even during the period of the emirate, that is, the governorship. Al-Andalus was a significant player in peninsular politics while maintaining strong ties with the Caliphate. Until the middle of the eighth century, power here belonged to various clans of Syrians, Arabs, and Berbers, who would sometimes form alliances and at other times engage in conflicts. In 750, the ruling Umayyad dynasty was overthrown in the Arab Caliphate, and the Abbasidsi

Qalam

In the ninth century, the Muslims annexed the Balearic Islands and introduced the Baghdad administrative system, which was considered advanced for its time and involved a high degree of centralization within the financial department and chancellery. Christian rulers in the north and northeast of the peninsula did not yet possess the strength for significant military campaigns in the south. Perhaps their most notable victory, under the protection of the Franks, can be considered only the capture of Girona and Barcelona in 801.

In 929, Abd ar-Rahman III (912–61) ascended to the Cordovan throne, assuming the title of caliph and ruler of the faithful and adding the honorary title "al-Nasir li-Din Allah" (the victorious warrior for the faith of God) to his name. From this point, the most splendid era in the history of Muslim Spain began. The caliph conquered the north African cities of Melilla, Ceuta, and Tangier, essentially establishing a protectorate over northern and central Maghreb.i

Al-Nasir also revived a tradition initiated a century earlier by Abd al-Rahman II, establishing official relations with the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus. Constantinople and Cordoba exchanged embassies and gifts. We also know that ambassadors from the German emperor Otto I were received at the court of Cordoba as well. Al-Nasir initiated these relations, anticipating that an alliance with the German ruler could be mutually beneficial in the struggle against a common enemy, the Fatimids,i

Finally, the abbot of the Gorze Monastery, a man named John, volunteered to go, being more enthusiastic about the idea of a martyr's death at the hands of the infidels than about carrying out a diplomatic mission. Accompanied by a priest sent as an envoy to the king and some servants, he carried the royal letter, which affirmed the truth of the Christian faith and condemned the Muslim faith. The contents of this message became known in advance at the caliph's palace and throughout the city, causing unrest among the people and becoming a serious obstacle to the meeting between the ambassador and the caliph. Al-Nasir could not let such an insult to his faith go unpunished, and therefore, he simply refused to receive the embassy.

For many months, John and his companions lived in a palace near Cordoba, enjoying various luxuries and respect but without any progress in their mission. The caliph sent various individuals to meet the abbot, including an educated Jew who informed him about Muslim customs and codes of conduct, advising him to be cautious in his conversation with the caliph. Then a Christian bishop approached him, requesting that he only present gifts to the caliph, concealing the king's letter, explaining that it could harm all Christians in the caliphate. Later, when the abbot was going to church for a prayer service one Sunday, he was handed a letter from the caliph himself, threatening him with severe punishments for him and all his co-religionists, urging him to reconsider his actions. But all was in vain: John sent a response letter to the caliph, affirming that he would fulfill the mission entrusted to him by the king until the end and deliver the message, even if he were subjected to torture and excruciating pain. Finally, the caliph ordered his people to ask John how to untie this knot, and the abbot replied that it was necessary to obtain new instructions from Otto in written form. Thus, another embassy was sent to Germany, led by Bishop Resemund, who was proficient in Arabic and Latin. He was warmly received by the king and, along with Dudo of Verden, the new envoy of the king, brought new gifts and instructions to Cordoba: the first letter should not be handed to the caliph; instead, present the gifts and establish an alliance. Upon the arrival of the second embassy in the capital of the caliphate, Al-Nasir finally had the opportunity to meet all the ambassadors and forge an alliance with his distant northern neighbor. After the first audience, the caliph also met John for a conversation, and the Muslim ruler discussed topics such as wisdom, power, glory, military art, wealth, successes, and the weaknesses of Otto with him. According to the Christian abbot, Abd al-Rahman showed excellent knowledge of political affairs in Germany.

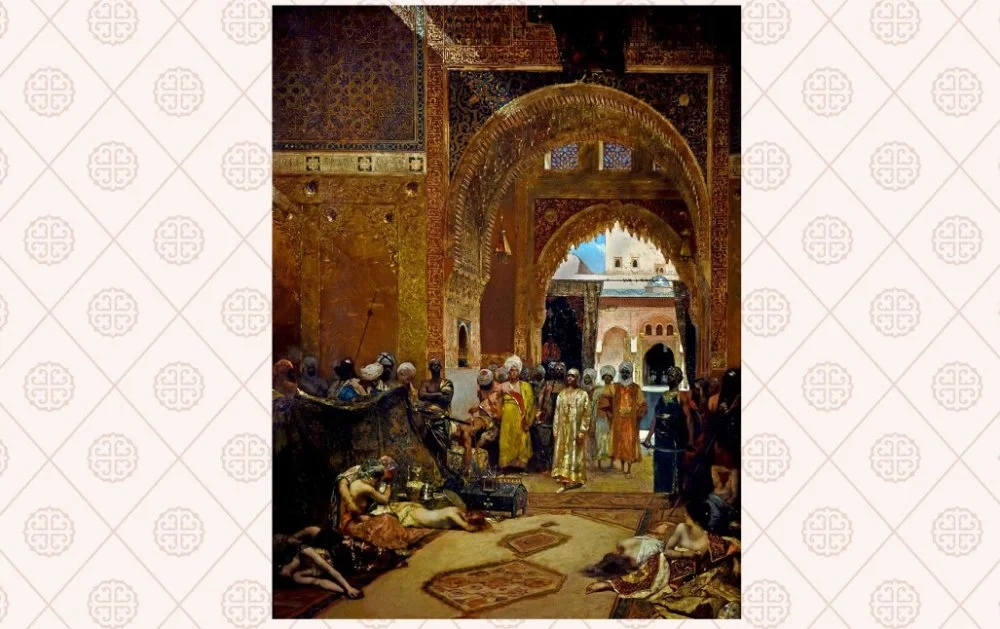

Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant. The Day after a Victory at the Alhambra. 1882/ Alamy

Continuous diplomatic relations existed between the caliphate and the Christian rulers of the peninsula and the lands beyond the Pyrenees. The Count of Barcelona, the Count of Provence, the Viscountess of Carcassonne, and the Queen of Pamplona were all interested in the patronage of the caliph and sought alliances with Cordoba. The caliph assisted Toda, the Queen of Navarre, in restoring her own rights and the rights of her son to the Navarrese throne. The caliph acted as a mediator in the conflict between King Ramiro II and his brothers, Ordoño and Sancho. In return, Abd al-Rahman demanded that the northerners pay tribute to Cordoba and pledge a vassal oath.

The caliph constructed a whole series of magnificent architectural monuments in Cordoba, but unfortunately, only a few have survived to this day. The most famous among them are the Great Mosque of Cordoba and the palace complex of Medina Azahara, located outside the city. It was the residence of the caliph, including private chambers, palace halls, utility buildings, and offices for officials—all that represented a true administrative city. According to Arab historians, Medina Azahara was founded in 936, and a whole army of craftsmen participated in its construction. 6,000 bricks were produced daily, not to mention tiles and finishing materials. Construction required 4,000 columns, the majority of which were imported from Carthage, while some, made of pink and green marble, came from a church in Ifriqiya. Onyx from Malaga and white marble from the quarries near Almeria were also used. Architects and craftsmen from Byzantium and Baghdad worked here, and masters from the Levant were invited to work on the decoration and interiors of the palace. The splendor of the palace and the Great Mosque of Cordoba presents us with a marvelous example of art that combines European and Eastern traditions. The ability to unite them was undoubtedly one of the greatest strengths of Al-Andalus.

One of the last brilliant rulers of the Cordoba Caliphate was Ibn Abi Amir, a courtier who did not belong to the Umayyad dynasty but who skillfully seized power during the reign of weak caliphs. Interestingly, his courtly career was greatly influenced by the support of the Basque concubine of the caliph, Subh. Although Subh (meaning "dawn") was a slave, as the mother of the caliph’s heirs, she wielded immense influence. This remarkable woman, who was involved in the political life of the caliphate for twenty years, had an extensive education: she was trained in singing, had knowledge of poetry, and was well-versed in jurisprudence.

Ibn Abi Amir restructured the army, organizing it based solely on the type of weaponry, departing from the previous tribal and territorial principles of organization. The number of Christian mercenary units in the army were increased as well. Being an excellent strategist, Ibn Abi Amir earned the nickname al-Mansur Bi'llah’, meaning the victor by the grace of God’. He successfully resisted the Fatimids in Africa, returning home on the backs of resounding victories and carrying rich trophies from numerous campaigns deep into Christian territories. Christian chronicles and romancero narrate devastating attacks by Almanzor (a Latinization into Spanish of al-Mansur), the destruction of the shrine of St James of Compostela during the 997 campaign against Galicia, and the plundering of Barcelona in 985. The kings of Leon and Pamplona, as well as the Count of Barcelona, were vassals who paid tribute to Almanzor. He intervened in internal conflicts, supporting kings loyal to the caliphate, deploying garrisons on their lands and maintaining control. By the end of his reign, only certain lands in Castile and parts of Asturias and Galicia retained some degree of practical independence.

With the death of this all-powerful royal official and later his son, the glory of Cordoba declined, and the era of the new taifas began, among which the Emirate of Granada became the most famous. Taifas were small political entities that constantly shifted their boundaries due to disputes between emirs, who began seeking alliances with Christian rulers and often became their vassals and paid tribute. Muslim gold became a major source of income for Christian ruling houses during this time. Therefore, Christian kings and counts preferred to see the emirs as their subjects, and sometimes even as relatives, rather than military adversaries. This state of affairs, of course, allowed for significant political maneuvering and diplomatic games on the part of both Muslims and Christians.

Emirate of Granada

During the thirteenth century, the political landscape of the Iberian Peninsula underwent significant changes. Extensive territories that were once under Muslim rule, with their prosperous cities, markets, flourishing gardens, and fertile pastures, came under the rule of Christian kings of Castile, Aragon, and Portugal. The taifas of Cordoba, Seville, Valencia, Murcia, and others ceased to exist. By the beginning of the fourteenth century, only the Emirate of Granada, which included the lands of Almeria and Malaga, retained its practical independence while becoming a vassal of Castile. It exploited the contradictions between its Christian neighbors on the peninsula and its Muslim neighbors in North Africa.

Indeed, Granada was a coveted prize, desired by both Christians and Muslims alike. Its role as a mediator between Europe and the trans-Saharan trade, its prosperous ports, extensive commercial connections, and textile production were of universal interest. Granada also held a significant portion of the Western European silk market, and through trans-Saharan routes, it received gold, which Europe desperately needed, as it lacked any significant sources of this noble metal.

To the same extent as all the later taifas of Al-Andalus, the Granadan emirate represented a uniquely Andalusian or Muslim-European phenomenon. It belonged entirely to the Islamic West. Its rulers traced their genealogy back to the first Arab families that landed on the peninsula, and in their way of life, they belonged to the Andalusian community: they spoke the local dialect of Arabic and the local Romance languages, could dress themselves according to European fashion, and politically oriented themselves towards the customs of their Christian neighbors. For example, in practice, the status of the Granadan emir resembled that of a king, which is more than a caliph. Moreover, they were included in the strictly European system of vassalage, while still maintaining traditional governing bodies, social structures characteristic of the Muslim world, and their Islamic identity.

In the fourteenth century, Granada was considered one of the most populous cities in Europe. In 1311, Aragonese travelers reported to Pope Clement that 200,000 people lived there, which was certainly an exaggeration, but Granada captivated their imagination. Eastern travelers admired its beauty and likened it to Damascus. Most likely, during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the city covered an area of about 170 hectares, and its population reached 50,000 people. Unlike the major cities known on the peninsula since Roman times, such as Zaragoza, Cordoba, and Toledo, Granada was a center founded by Muslims.

The city had double walls that ran from Alhambra, the upper city, to the lower city. Within these fortifications, the eleventh-century walls that surrounded the old quarters, Alkasaba Kadima and the Jewish quarter of Juderia, were preserved until the sixteenth century. In many ways, Granada was a typical Hispano-Muslim city. Its core, the madina, was located on the flat territories of the left bank of the Darro River. Wide streets surrounded the Great Mosque, with no other buildings attached to it. This area housed facilities for studying religious sciences, witness stands, and apothecary shops. Not far from the mosque was a school with classrooms, a prayer hall, and rooms for students.

The madina had many bazaars, the most famous of which was the Qaysariya, renowned for its luxury goods and fabrics, and it had its own walls. Covered stalls formed entire streets inside it, and at night, it was closed off by ten gates. On the left bank of the Darro River was a commodities exchange market and a quarter with warehouses that were rented out to foreigners. This quarter was connected by a bridge to the Qaysariya market and the Great Mosque square. Besides this bridge, the city had four more bridges.

With the advance of the Christians to the south, Granada underwent significant expansion and grew with new neighborhoods that absorbed Muslim settlers from the north, giving rise to areas such as Albaicín and Antequeruela. Above the lower city, the Alhambra rose, transformed by the emirs into a true Islamic western city with all its components: palaces, residential quarters, a mosque, bazaars, fountains, baths, and services. From here, one could see palaces, fortified towers, white country houses nestled in gardens, and dense forests on high hills.

Francisco Pradilla Ortiz. The Surrender of Granada. 1882. Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

The sunset of Al-Andalus

The policy of the Granada emirs, skillfully forming alliances and accepting vassal obligations, yielded good results until the forces of Castile and the Crown of Aragon united. In 1479, a dynastic union was established between Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, which immediately made Granada vulnerable. Over the course of ten years, the Christians gradually advanced southward, and by the end of 1491, the queen ordered the construction of a fortress named Santa Fe (Holy Faith) near Granada, leaving the Granadans with no hope.

On 1 January 1492, the last emir of Granada, Muhammad XII, known as Boabdil (Abu Abdallah) in Spanish, signed the instruments of surrender in Santa Fe. The next morning, he handed over the keys to the city and left it forever. According to a Spanish legend, as Boabdil was leaving the surrendered Granada, he looked back at his city, and his mother, Aisha, who had done much to enable and maintain his rule, said, "You weep like a woman for what you could not defend as a man."

However, the historical truth was that the Granada emirate, as a political entity, belonged entirely to a medieval paradigm of governance that was fading away in Europe, with its pluralism, its religious and ethnic diversity. The newly formed state resulting from the union, led by ambitious young Catholic monarchs, had already built ships that would set sail to discover America and turn the page of world history. There was no place for the small southern vassal in the unified system of the national Catholic state.

At the same time, the fabulous wealth of Granada attracted northerners no less than Constantinople attracted the Crusaders in 1204.i

The experience of the Granada emirate is extraordinarily interesting precisely because of its synthesis of European, North African, and Eastern elements, which bore wonderful fruits in Andalusia, a land that absorbed the customs and blood of inhabitants from wild deserts, multilingual ports, bustling capitals, formidable castles, and whitewashed urban quarters.

On 6 January 1492, Catholic monarchs ceremoniously entered Granada. It was undoubtedly the largest triumph of Christian weaponry. Muslim rule on the Iberian Peninsula came to a definitive end and gradually began to fade from memory. The day Granada was seized soon became a national holiday in Spain—incidentally, it was the first instance of a secular "state" holiday in the country. Legends were woven about the Moors, wandering Khuglarsi

But what about the people, you might ask? What happened to the Muslims who traded the famous Granada saddles, silks, and vases, who cultivated gardens and vineyards, and cooked sweet couscous? What happened to those who called all twenty-six gates of Granada not by the Spanish word "puerta" but in the Arabic manner, with a distinct Andalusian pronunciation, "bib": Bib-al-Harma (Red Gate), Bib-al-Rambla (Gate of the Ears), Bib-al-Difaf (Gate of the Drums), and so on. After all, we began our story from the perspective that Muslim Europe existed not in the laws of kings and caliphs, not on the edges of swords or through preachings, but in the natural course of life for many, many different people.

In answering this question, it should be noted that many prominent Muslims left Granada because they were unwilling to live under the rule of the Christian kings. However, the majority stayed. This was their home, their land, the homes and lands of their fathers and grandfathers. They belonged here. How their destiny unfolded and what paths Muslim Europe took after Islam lost its status as a political hegemon here is the next chapter of our history.

Edwin Lord Weeks. Interior of a Mosque at Cordova. 1880/ Alamy

Al-Andalus Power and Society

Let us look back at the magnificent al-Andalus, created by Muslims in Europe, the pearl of medieval Europe. From the beginning of the eighth century until the first decades of the thirteenth century, Muslims held the majority of the Iberian Peninsula. Even after losing their prominent political position in the region, they continued to be formidable military opponents and a political force that could not be ignored. They were seen as bearers of high culture, deep knowledge, and wisdom. The way of life, governance systems, economic policies, and education the Muslims introduced to the peninsula were entirely new and replicated Near Eastern models. Neither the Romans nor the Visigoths, who were in the peninsula before the Muslims, knew those social strategies formulated by Islam.

As we know, since Prophet Muhammad’s time, Jews and Christians were granted a special status as "People of the Book", which imposed on them the obligation to pay a special tax called jizya. Muslims were exempt from paying this tax, but it ensured the preservation of their faith, laws, and communities. Although Jews and Christians in al-Andalus were limited in their ability to pursue political careers, for the ordinary population, such as peasants, artisans, and merchants, life under Muslim rule proved to be much more attractive than life under the Visigothic regime. The swift conquest of the peninsula by Muslims was also largely facilitated by the favorable disposition of the local population, who were oppressed by taxes and restricted in their rights, including slaves and Jews.

The Muslims encouraged conversion to Islam by promising a reduction in the tax burden and social advancement. Anyone who converted from Christianity or Judaism to Islam gained access to participation in political governance, and every slave obtained freedom. Many influential Visigothic families embraced Islam and were integrated into the governance system established by Muslims in the former lands of the Visigothic monarchy while retaining their lands. Andalusian biographical collections mention notable clans such as the Banu Sabarico and Banu Angelino of Seville, the Banu Qasi, the Banu Karlamah, the Banu Marti, and the Banu Garcia. The famous Cordoban poet, theologian, and historian Ibn Hazm also hailed from one such family. Ibn al-Qutiya, a renowned Spanish-Muslim historian whose name in Arabic means "son of the Goth", considered himself a descendant of Princess Sara, the granddaughter of the penultimate Visigothic king Wittiza.

When speaking about slaves, it should be mentioned that slavery in Islam was fundamentally different from the ancient world: slaves had the status of domestic servants. The personal guards of the caliphs were composed of black slaves. During the reigns of al-Hakam II and al-Mansur, no military campaign took place without the active participation of the Sudanese division. In the cities, there were even more black slave women than male slaves because they were highly valued for their work in household chores and as concubines.

Otto Pilny. The slave market. 1910 / Wikimedia Commons

Palace slaves, including eunuchs and others, in the Cordoban caliphate were predominantly of European origin. They were referred to as saqaliba, which meant "Slavs". In reality, this term usually encompassed prisoners from continental Europe, ranging from Germany to Slavic lands, who were then sold in Muslim territories and Byzantium. According to Ibn Hawqal, an Eastern traveler of the mid-tenth century, slaves in Cordoba came not only from the shores of the Black Sea but also from Calabria, Lombardy, Frankish Septimania, and Galicia. Among those were individuals with exceptional political and military talents who made brilliant careers at the courts of emirs and caliphs. Often, slaves became free men, wealthy individuals who owned their own slaves.

During the caliphate period, there were also captive women, Christians, and fair-skinned blonde individuals among the captives brought from Gascony, Languedoc, the Spanish March, and Basque country, and later during the taifa period from Christian territories in Spain. The emirs and caliphs chose concubines from among them, while prominent officials and wealthy merchants purchased slave women. Some argue that the bloodline of Al-Andalus rulers was so heavily "diluted" due to constant unions with Christians that it almost lacked a genetic Arab component.

The penultimate emir of Granada, Abu al-Hasan Ali, married Isabella de Solis, a girl from a noble Castilian family who was kidnapped and sold as a slave in Granada. Isabella converted to Islam and took the name Soraya, and she gave birth to two sons of the emir. After the fall of Granada, she lived in Cordoba and later in Seville, refusing to leave Islamic lands, initially remaining loyal to Islam. However, when Muslims were forced to convert to Christianity, she returned to the Christian faith and both her sons were baptized.

Thus, the political influence and cultural charm of al-Andalus cannot be overstated.

Latin Europeansi

Ludwig Deutsch. The Nubian guard. Late 19th century / Alamy

In the ninth century, a Christian named Paulus Alvarus, from a noble and wealthy family, lamented in his writings that Christian youth struggled to string together a few Latin words but took pleasure in composing poetry in Arabic. In addition, elements of Eastern clothing, including turbans, were fashionable in the northern part of the peninsula.

Prominent Christian noble and ruling families eagerly formed dynastic marriages with Cordovan caliphs and taifa emirs. For example, Princess Onneca of Navarre was married to the future Cordovan emir Abdullah ibn Muhammad. It is possible that Onneca converted to Islam and held the status of a wife in the harem. Arab sources referred to her as Durr, meaning "pearl". This marriage aimed to strengthen the ties between the powerful Iniguez family in the north and the brilliant Umayyads. In Cordoba, Onneca gave birth to two daughters and a son, who was destined to inherit the throne, but he became the victim of a conspiracy. When Abdullah was on his deathbed, he named not one of his sons as his successor but his grandson, the child born three weeks after his father's death, to his Christian concubine Muzayna, of Basque origin. From his grandmother and mother, the future great caliph Abd al-Rahman III inherited fair skin, blue eyes, and light reddish hair, which he dyed to resemble an Arab more. It is not surprising that he spoke Romance languages either.

Throughout its history, the farthest and westernmost part of the Islamic world—one could call it a province—al-Andalus, faced Mecca. It was caressed by the hot breath of the Sahara and the harsh northern winds. It provided humanity with an astonishing experience of cultural integrity, the ability to engage in intercivilizational contact while maintaining its own Muslim-European identity.