Portrait of Russian-born American writer Vladimir Nabokov (1899 - 1977) standing with a butterfly net outdoors in the hills of Switzerland/Horst Tappe/Getty Images

Celebrating 125 years of one of the twentieth century’s greatest writers

In a 1966 interview, Vladimir Nabokov confessed that he preferred to write his books in a non-linear manner (and not chapter by chapter!), in chunks, using index cards, and filling in the blanks at random. There is no doubt that Nabokov created a universe of his own—his images have so powerfully permeated through our lives that they appear in the most unexpected contexts. A year and a half ago, for example, a book by Nabokov was featured in a commercial for a real estate development company in Almaty. And so, in this article, the editors at Qalam have tried to emulate his method and used a fractional structure instead of a single narrative. We tried to imagine what the alphabet of Nabokov’s universe might look like.

We decided not to talk about chess, butterflies, or nymphets for the hundredth time, and focus instead on the less hackneyed aspects of Vladimir Nabokov’s work.

This is the first part of Vladimir Nabokov's ABCs. The second part you can read here.

A Is for Ada

This 1969 novel, which led to one of Nabokov’s nominations for the Nobel Prize (that failed to win it, like all the others) resonates strongly with Dovlatov’s story about how the famous linguist Roman Jakobson took exception to Nabokov’s appointment at Harvard University. When it was proposed that Nabokov be offered a job as professor of Russian literature because he was ‘after all, an important writer’, Jakobson immortally remarked, ‘Gentlemen, even if one allows that he is an important writer, are we next to invite an elephant to be Professor of Zoology?’

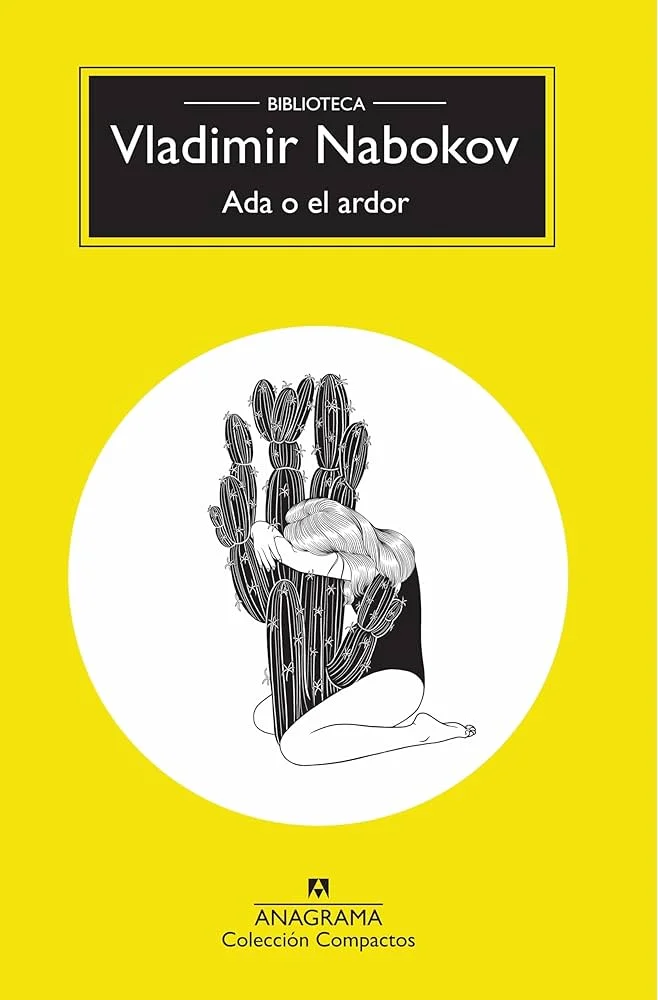

Spanish edition of «Ada»/from open access

Ada is the best proof that Nabokov is indeed an important animal. 700 pages in three languages (and three different translations into Russian) are the culmination of Nabokov’s method and style, teetering delicately between grandiose excess and precise balance. The baroque excess of this incestuous family saga reaches such proportions that it threatens to bring down the entire edifice and bury its enamored heroes beneath it. But these characters are not to be pitied—there is nothing to pity in their cruel, selfish passions and their predisposition for fried bear cubs. One can, however, love them passionately. The degree of sinful love in this novel most likely surpasses even Lolita. As for the scandalous subject of incest, Nabokov said that it was as important to him as an insect since these words use exactly the same letters in English.

In the Russian-speaking world, artists are still arguing about how to properly turn Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita into a movie and whether it is even possible. However, the great Nabokov scholar, Brian Boyd, has long nurtured the idea of making a TV series based on Ada (sixty-nine episodes corresponding to the number of chapters in the book), which could be a real challenge for the TV industry. The same Boyd has been engaged for years in a titanic project to provide commentary on Ada, which can be found at.

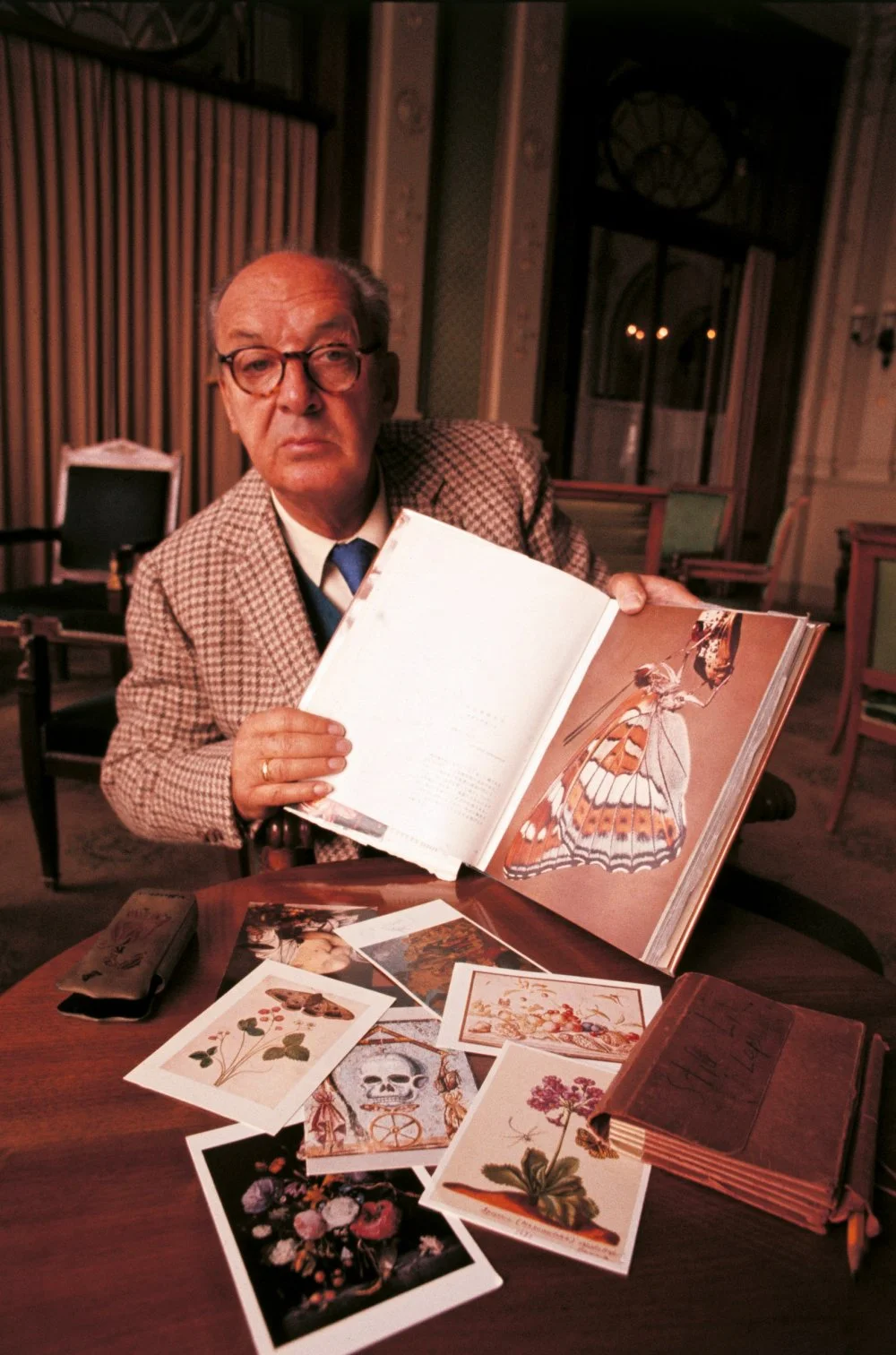

Russian-born American writer Vladimir Nabokov showing some drawings leaning on a table. Montreux, October 1969/Giuseppe Pino/Mondadori via Getty Images

Since the project is still a work in progress, I also dare offer my own modest commentary on one of the novel’s passages: when Lucetta, filled with erotic energy, suggests that Van bind her, we may be looking at an allusion to Lucy Westenra from Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

B Is for Beetle

‘Are you glad to be going to Berlin?’ Martin gloomily asked.

The very structure of this sentence from the novel Glory reveals Nabokov’s attitude to the city. Nabokov genuinely disliked Berlin (as did the famous singer and poet Alexander Vertinsky!), and during his fifteen years there he never learned German despite the fact that it was in this city that he made his name as a writer.

The city sometimes has its own ‘primeval paradise’, as he wrote in The Gift, and ‘even Berlin could be mysterious’.

But for the most part, Nabokov’s Berlin is a city of adultery, murder, ‘murky nausea’ in the eyes of officials, vicious German maids, elderly harlots, dimly lit corridors, ‘shabby hotels’, ‘eccentric cyclists’, ‘clumsy buses’, ‘dodgy streets’, ‘dusty gloom’, and ‘disgusting beer houses’ serving cold pork. Even Berlin’s tarmac appears to him to be ‘smeared with black lard’, with ‘spooky holiday streets’ abounding on New Year’s Eve.

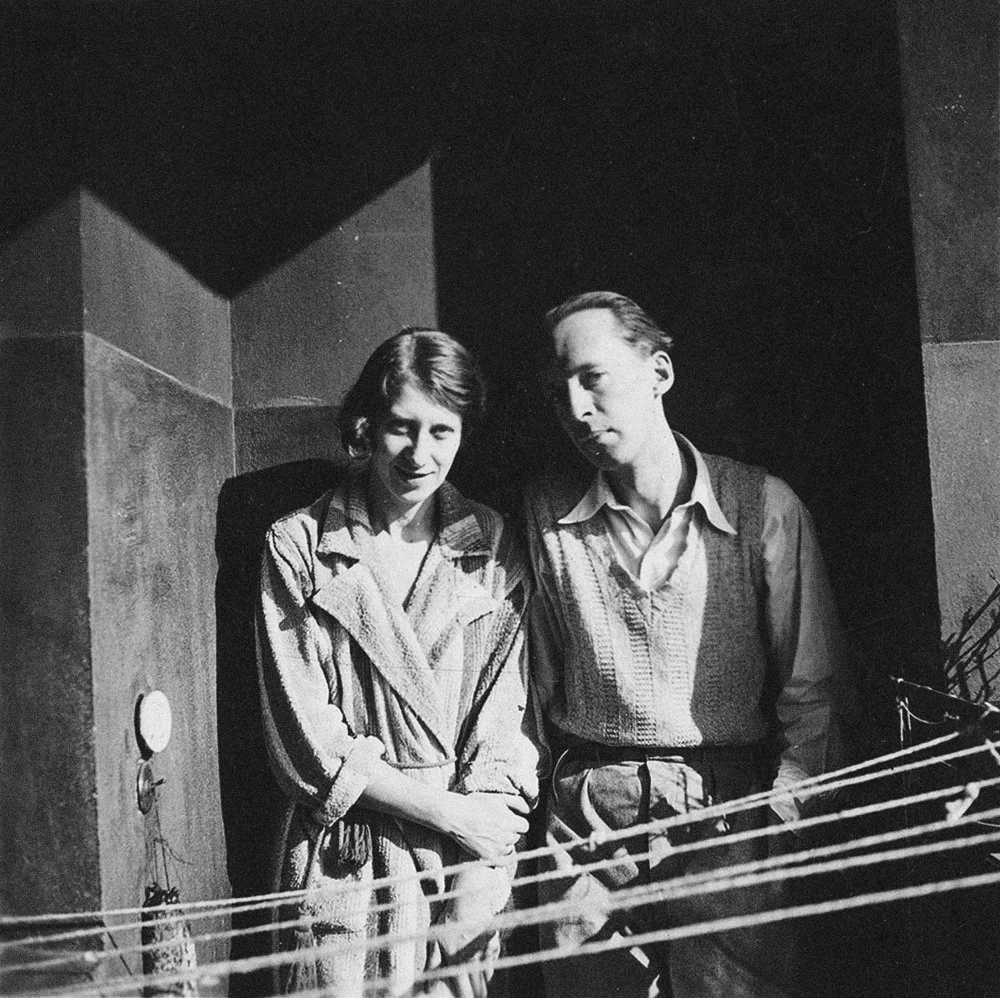

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov (1899-1977) and his wife Vera Nabokova (1902-1991) in 1923/Alamy

Such despondency can easily be explained by the writer’s personal circumstances. Nabokov saw Berlin with its ‘stingy’ inhabitants through the eyes of a refugee. While his first two addresses, on Egerstrasse and Sächsische Strasse, resembled human habitation, his wife and he later had to make do with varying degrees of squalor in shacks with shared bathrooms.

It was also in Berlin that Nabokov’s father was assassinated, and his brother Sergei died in Neuengamme Concentration Camp. In his late novel Pnin, the hero’s first love, Mira Belochkin, perishes in Buchenwald. Nabokov himself left Germany in 1937 and never returned.

Interestingly, in Glory, when Martin asks Sonya if she is glad to be going to Berlin, she replies, ‘I don’t care.’

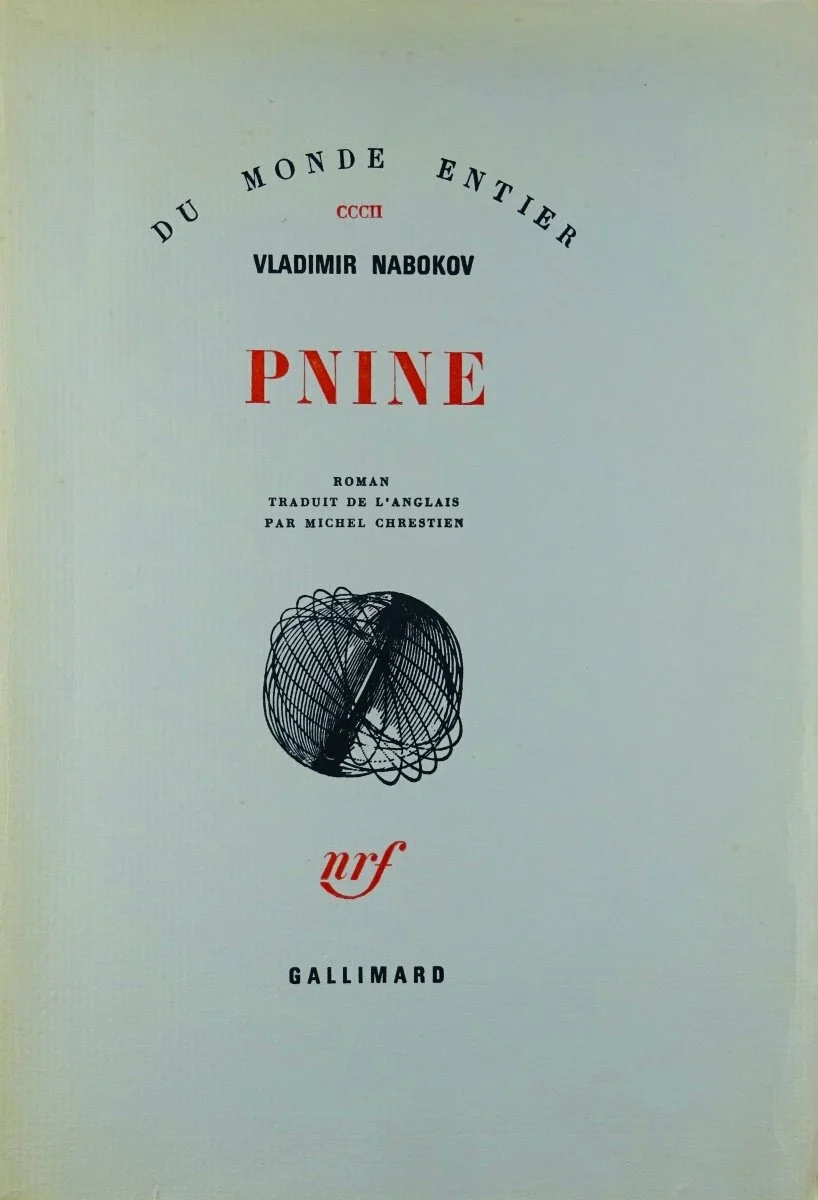

The cover of the novel "Pnin" (France)/from open access

B Is for Beetle

Nabokov left dozens, if not hundreds, of images that remain in our memories, that live on as if separated from the context. For example, one may not remember all the vicissitudes of The Defense, but it is impossible to forget the tiny episode when little Luzhin has ‘quite a time crushing’ a beetle ‘beneath the stone’, trying ‘to repeat the initial, juicy scrunch’. Interestingly, Nabokov’s favorite epithets tend to repeat themselves; for example, in Invitation to a Beheading, a woman is called ‘a juicy little piece’. We chose the juicily crunching beetle simply as one of the best examples of Nabokov’s killer powers of observation (though, to be fair, some may prefer the comparison of an angel to a condor, the lunar volcanoes of mashed potato, or a shred of boiled beef firmly lodged in the teeth). This is what Nabokov himself called the ‘radiant independence’ of the detail.

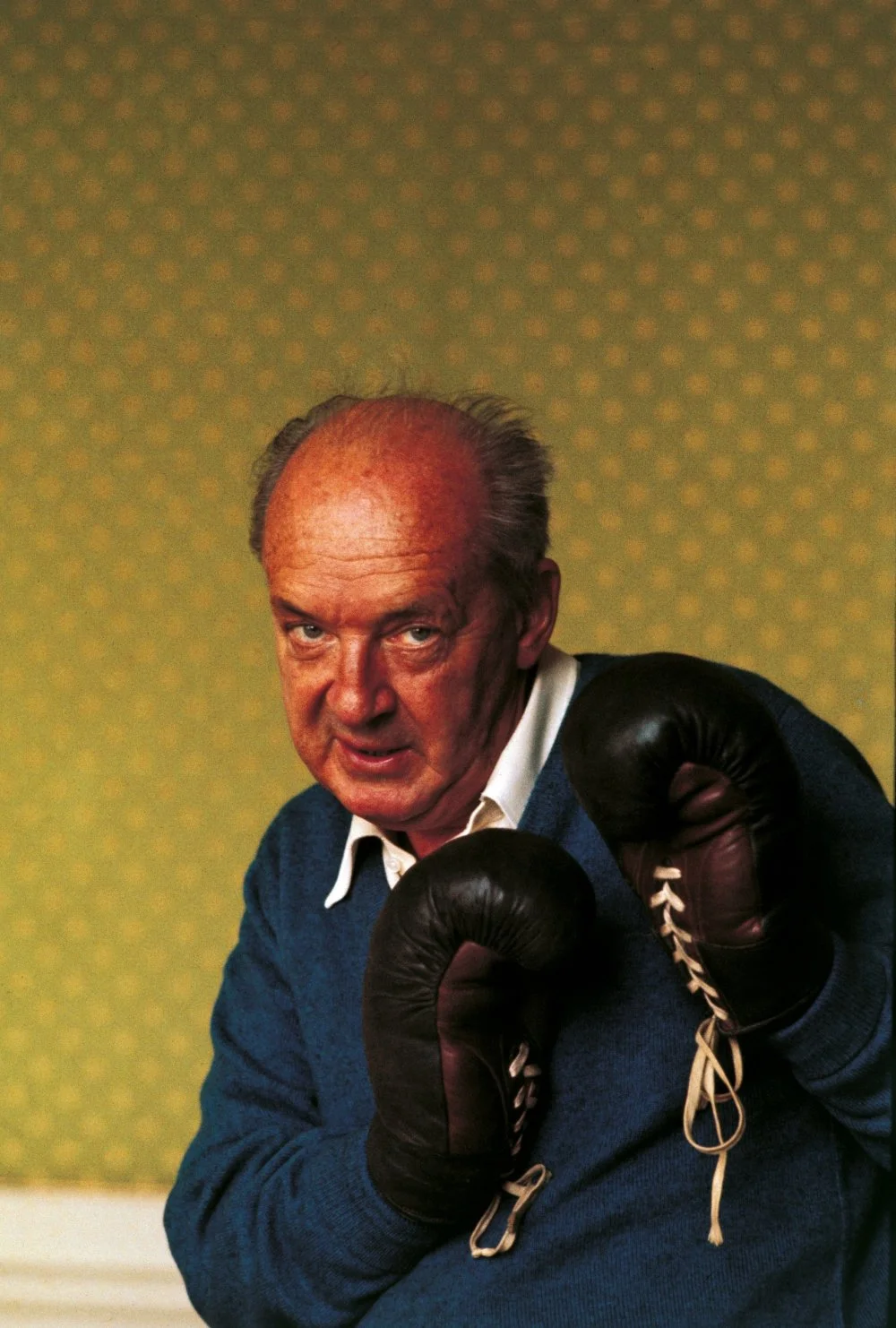

Vladimir Nabokov With Boxing Gloves/Getty images

Beetles are not butterflies, of course, but they are given their own modest place in Nabokov’s pages. For example, a book on the anatomy of bedbugs appears in Bend Sinister as a sign of a past life, and there is also a mention of a wrought pig iron shoe spoon in the shape of a huge stag beetle. In Look at the Harlequins! (1974), the theater Glowworm Group appears. Finally, a 1935 poem reads:

At sunset, you know the kind,

with a bright cloud and a cockchafer,

by a bench with a half-rotted plank

high above the ruddy river,

as it was then, in those far-off days,

smile and turn your face away.

G Is for Gardenia

It is a fact that butterflies are attracted to flowers, and Nabokov’s works contain a veritable herbarium: hydrangeas, irises, turquoise roses, lilacs, mimosas, lilies, forget-me-nots, orchids, fennel, hyacinths, and, as it is said on one occasion in the finale of Ada, ‘much, much more’. Nabokov himself, however, is known in oral history by the name of another flower.

The highly respected American literary scholar Edmund Wilson was once a friend and admirer of Nabokov, though they later quarreled and cursed each other roundly. His young son Reuel had difficulty pronouncing the name Vladimir, and he called the writer ‘Gardenia’. Nabokov did not object to this nickname, with Wilson adding, ‘You are the gardenia in the buttonhole of Russian literature.’

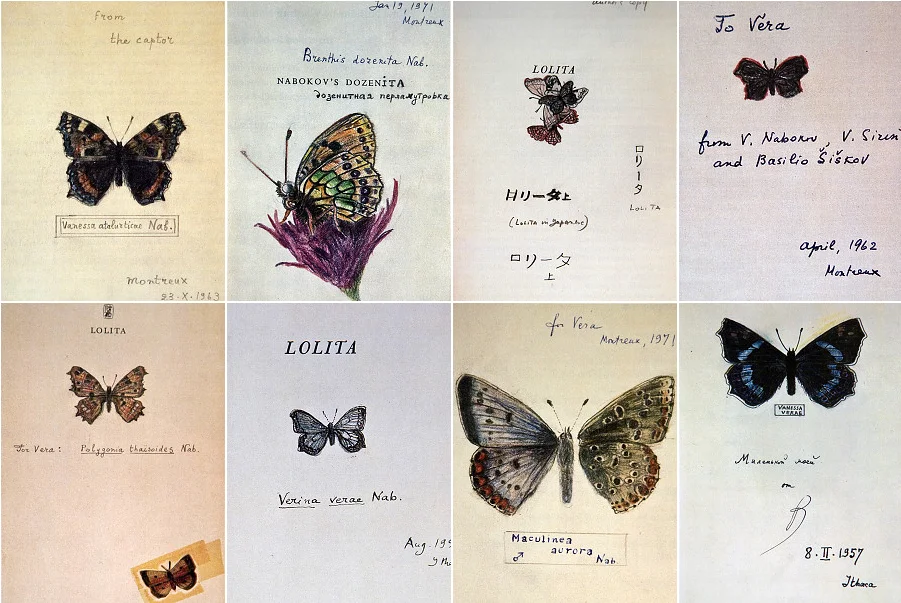

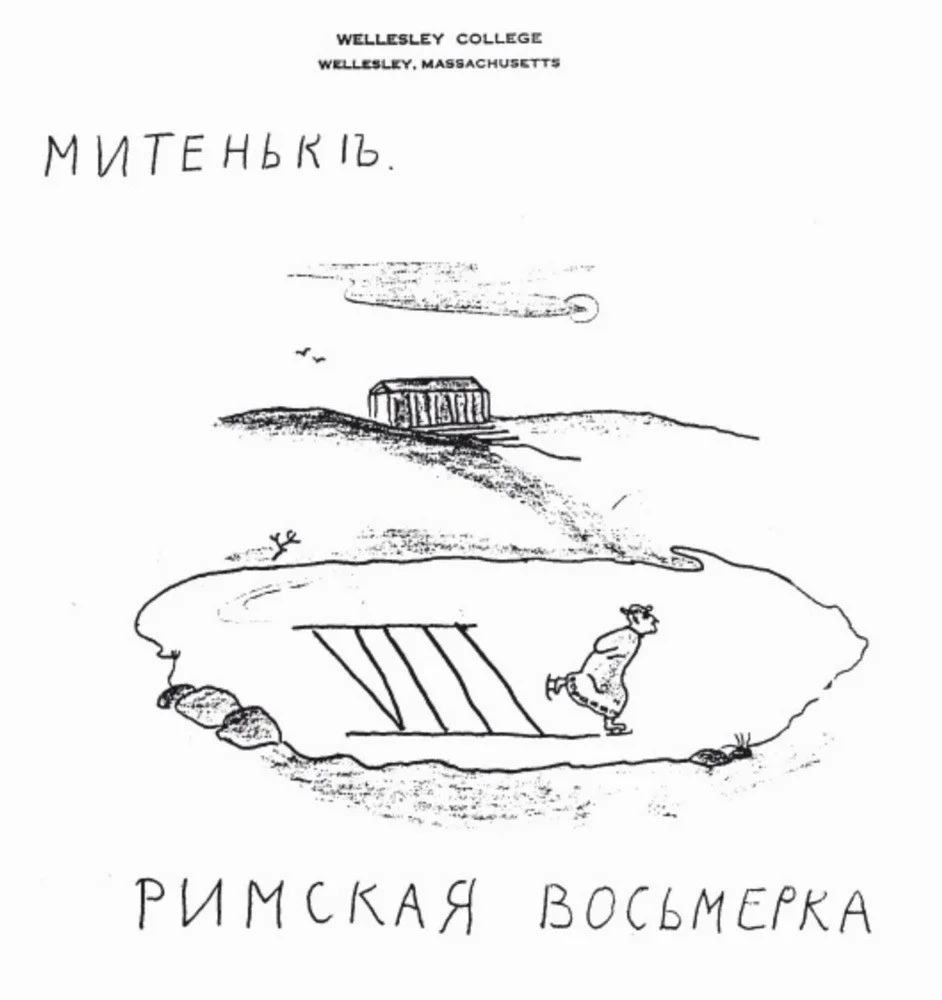

Nabokov's drawings/from open access

D Is for Doppelgänger

In Nabokov’s Despair, he writes, ‘Now tell me, please, what guarantee do you possess that those beloved ghosts are genuine; that it is really your dear dead mother and not some petty demon mystifying you?’

Despair is literally a novel about doubles, but the very principle of duality is revealed in all of Nabokov’s works in a variety of forms and texts: roll-calls, reduplications, repetitions, and reflections in the ‘sick mirror’ as seen in Despair. The fissure of the reduplicated world runs through the entire oeuvre: homeland and emigration, the earthly world and the hereafter, art and reality, man and his image. We should also not forget that Nabokov, not having achieved all that he wanted as a poet, simply transferred the principle of rhyme to his own prose, in which he was much more successful.

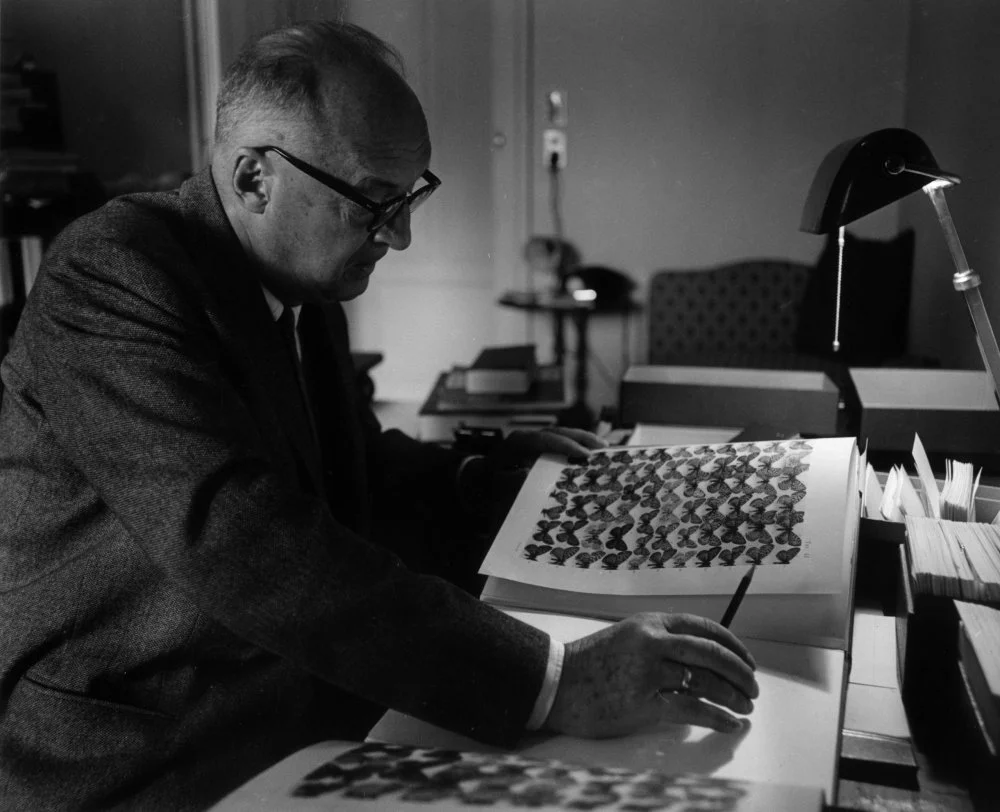

Russian-born writer Vladimir Nabokov (1899 - 1977) studies a butterfly chart in a book while sitting at a desk indoors, Switzerland/Horst Tappe/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The ‘double rumble’, as the writer himself once put it, becomes an elaborate game. For example, the surname Luzhin appears twice, once in the novel of the same name and once in a story with the flirtatious title ‘A Matter of Chance’. The passage of a man who wears only ‘trunks’ in public is first described in a deliberately degraded form in Despair (1934), then in The Gift. The obnoxious word ‘trunks’ itself, which occurs almost five times in The Gift, most likely paves the way for the later ‘cadaverkins’ (in Russian, these two words sound similar), which is the fancy name given to unborn babies in the story ‘Ultima Thule’.

The phrase ‘pale fire’ first appears in The Defense and later becomes a full-fledged novel on its own. Metaphors also tend to be duplicated in different works: Argus-like scrambled eggs and Argus-eyed hall.

Nabokov once complained in an interview that he was haunted by ‘a good, long nightmare with unpleasant characters imported from earlier dreams, appearing in more or less iterative surroundings.’ One can’t help but think of the man in The Gift who has been mimicking someone else’s speech for so long that he has begun to speak like that other person.

The cover of the novel "The Gift" (Japan)/from open access

The evil in Nabokov’s texts is often doubled. In Invitation to a Beheading, the lawyer and the prosecutor are supposed to be half-brothers. In the same novel, an executioner named M’sieur Pierre keeps taking pictures of himself (and the same Pierre has an affair with the absurd bridge-pass guard Pietro from Bend Sinister).

In his old age, however, Nabokov suggests a possible way out of this two-worldliness, which is forward into a three-worldliness. In his last novel, Look at the Harlequins!, he writes, ‘Put two things together— jokes, images—and you get a triple harlequin.’ Again, the image itself is not new, having been encountered in The Gift, where there are ‘harlequin rhombuses of colored light’ and ‘poems iridesce with harlequin colors’.

Hungarian edition dedicated to Nabokov's work/from open access

In Nabokov’s case, however, the best story about doppelgängers and originals belongs to his life. In 1999, The Nabokovian magazine held a contest of Nabokov imitations: readers were invited to choose the most successful one. The writer’s son submitted two fragments of Nabokov’s unpublished and unfinished novel The Original of Laura. None of the participants recognized Nabokov in these texts.

G Is for Gospel

Nabokov’s art is rarely associated with the religious sphere, and as such, the confessional genre irritated him as did the public nature of any ritual. Evangelical symbolism appears mainly in his early poems, such as ‘On Golgotha’, ‘Easter’, and ‘I Saw the Vaults of the Sky Grow Dark’. In a poem dedicated to Blok, Nabokov describes paradise as such, and this paradise is extremely literary, or, rather, poetic. In it, Pushkin becomes a rainbow, Lermontov the Milky Way, Fet a blushing ray in the temple, et cetera. There is every reason to believe that Nabokov, at least in his later years, included himself in this pantheon. As he said in an interview in the 1960s, ‘A creative writer must study carefully the works of his rivals, including the Almighty.’

Russian-born writer Vladimir Nabokov (1899 - 1977) and his wife, Vera, walk in the park at Montreux Palace Hotel, where they lived, Switzerland/Horst Tappe/Getty Images

In his prose, Christian motifs recur. Nina in ‘Spring in Fialta’ gives everyone traditional Russian Easter kisses ‘with more mouth than meaning’, Luzhin recalls childhood nights at Easter and the sobbing bass voice of the deacon, and the narrator of Speak, Memory recalls the cobalt blue of the vaulted ceiling of a church. ‘If churches speak to us of the Gospel, zoos remind us of the solemn, and tender, beginning of the Old Testament,’ reads the story ‘A Guide to Berlin’. Nabokov’s characters never go to church. In the story ‘Easter Rain’, Joséphine, an old, lonely Swiss woman, paints Easter eggs, recalling only the ‘dusky sheen’ of St. Isaac’s Cathedral.

More often than not, religion appears in its anecdotal aspects: there is a poet in ‘Spring in Fialta’ who was able to represent, if you asked him, Adam’s fall using five matches. In ‘An Affair of Honor’, a character, advising the protagonist about a duel, says, ‘Put your trust in God and just press the trigger.’ The hero of ‘Wingstroke’ states that he does not believe in God, but he is nevertheless visited by the angel propping itself on its palms like a sphinx. Humbert in Lolita sneers that after good Charlotte Haze had become more or less his mistress, she interviewed him about his relations with God.

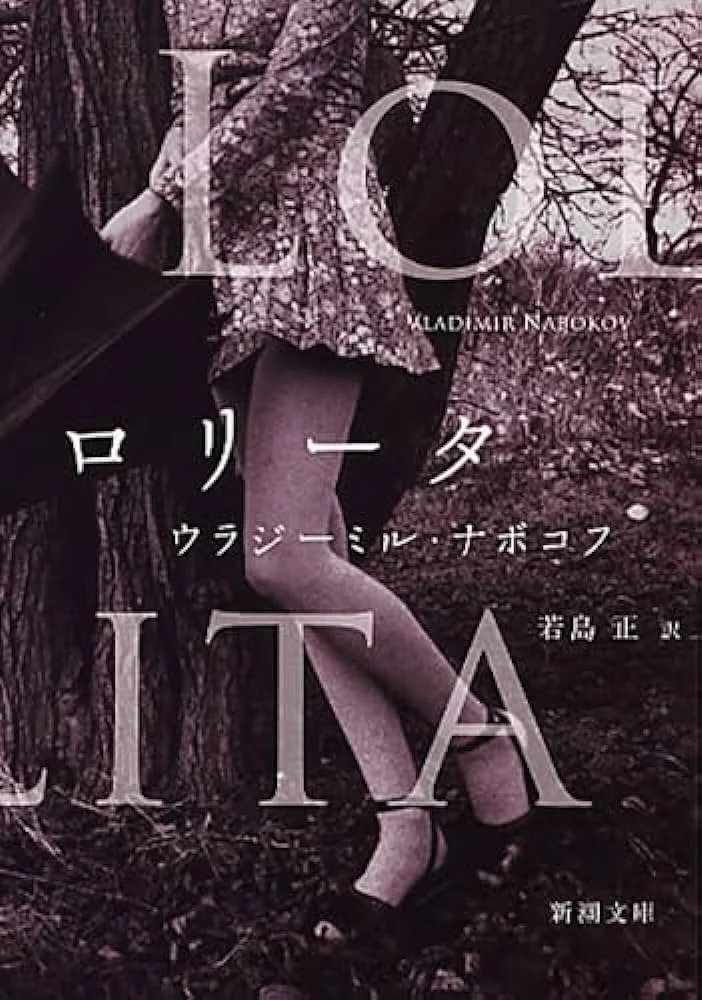

"Lolita" (Japanese edition)/from open access

Incidentally, such an interview occurred in Nabokov’s own life as well, described thus by Brian Boyd: ‘Out on a long stroll together, Wilson asked Nabokov whether or not he believed in God. “Do you?” countered Nabokov. “What a strange question!” muttered Wilson, and fell silent.’

Yet these unanswered ‘strange questions’ were in many ways the foundation of Nabokov’s prose. When he was once asked in an interview what surprises him in life, the writer replied, ‘The marvel of consciousness—that sudden window swinging open on a sunlit landscape amidst the night of non-being.’

The theme of confronting this ‘night of non-being’ is central to Nabokov’ works. The Gift contains the most bitter sentence about the (im)possibility of life after death: ‘There is nothing. It is as clear as the fact that it is raining.’ (In reality, there was no rain: the tenant upstairs was watering the flowers on the edge of her balcony.) Charles Kinbote, the half-crazed commentator from Pale Fire, realizes that ‘with no Providence the soul must rely on the dust of its husk, on the experience gathered in the course of corporeal confinement, and cling childishly to small-town principles, local by-laws and a personality consisting mainly of the shadows of its own prison bars.’

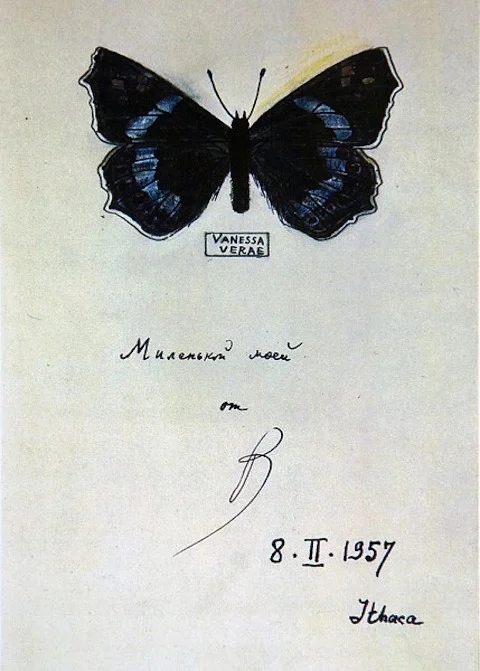

Photo by Vladimir Nabokov for his son Dmitry. Illustration from the book" Letters to Vera". Moscow, 2017/Publishing House"Kolibri"

Art, in Nabokov’s view, is the only thing that can save earthly life, which, in the short story ‘Christmas’ is described as ‘ghastly in its sadness, humiliatingly pointless, sterile, devoid of miracles.’ ‘Christmas’, which is about a man burying his son on Christmas Eve, can be generally considered as one of the most religious, if formally apostate, texts in Russian literature. The boy had collected butterflies, and his soul seems to have been reincarnated on Christmas Eve as a giant Indian silkworm.

Nabokov’s credo might sound like the conclusion of ‘A Letter That Never Reached Russia’: ‘The centuries will roll by, and schoolboys will yawn over the history of our upheavals; everything will pass, but my happiness, dear, my happiness will remain, in the moist reflection of a streetlamp, in the cautious bend of stone steps that descend into the canal’s black waters, in the smiles of a dancing couple, in everything with which God so generously surrounds human loneliness.’

B Is for Beetle.

Nabokov left dozens, if not hundreds, of images that remain in our memories, that live on as if separated from the context. For example, one may not remember all the vicissitudes of The Defense, but it is impossible to forget the tiny episode when little Luzhin has ‘quite a time crushing’ a beetle ‘beneath the stone’, trying ‘to repeat the initial, juicy scrunch’. Interestingly, Nabokov’s favorite epithets tend to repeat themselves; for example, in Invitation to a Beheading, a woman is called ‘a juicy little piece’. We chose the juicily crunching beetle simply as one of the best examples of Nabokov’s killer powers of observation (though, to be fair, some may prefer the comparison of an angel to a condor, the lunar volcanoes of mashed potato, or a shred of boiled beef firmly lodged in the teeth). This is what Nabokov himself called the ‘radiant independence’ of the detail.

Beetles are not butterflies, of course, but they are given their own modest place in Nabokov’s pages. For example, a book on the anatomy of bedbugs appears in Bend Sinister as a sign of a past life, and there is also a mention of a wrought pig iron shoe spoon in the shape of a huge stag beetle. In Look at the Harlequins! (1974), the theater Glowworm Group appears. Finally, a 1935 poem reads:

At sunset, you know the kind,

with a bright cloud and a cockchafer,

by a bench with a half-rotted plank

high above the ruddy river,

as it was then, in those far-off days,

smile and turn your face away.

Nabokov's drawing/from open access

H is for Health.

In the preface to his early American novel Bend Sinister, Nabokov writes, ‘My health was excellent. My daily consumption of cigarettes had reached the four-package mark.’ The cult of health is characteristic of both Nabokov himself and his characters. Fyodor Godunov-Cherdyntsev, the central character of The Gift (and in many ways the author’s alter ego), an athletic practitioner of ‘obscene sporty nudity’, takes tireless walks in the woods, sunbathes naked, and unwittingly amuses the police by walking through the city in his underwear. The hero of Glory, Martin Edelweiss, is a skier, soccer player, and tennis player with a terracotta back and a ‘powerful figure’. Ganin, in Mary, can walk on his hands and break a string by flexing his biceps.

These health metrics apply fully to literature. Dostoevsky and Chernyshevsky are bad simply because their prose is sickly, while The Gift suggests that reading Pushkin can enhance a reader’s lung capacity.

The male characters dear to Nabokov hardly ever drink at all. ‘Bad liquor’ is what he calls it in The Gift. Luzhin invariably orders mineral water. Ganin in Mary reprimands Alferov for drinking. But the vulgar Ardalion from Despair drinks (‘First show me where you’ve chucked my vodka.’). Among his positive characters, only Krug, who recently buried his wife, carries a flask with brandy to help him to live through the day and likes cider. In general, however, Nabokov is only interested in ‘a drop of vodka in which a mauve trace of indelible pencil was spreading’, as in Mary.

Russian-American writer Vladimir Nabokov posing on the terrace of Montreux Palace Hotel, where he is staying. Montreux (Switzerland), 1973/Walter Mori\Mondadori/Getty Images

But Nabokov would not be Nabokov if he did not draw a vicious and vulgar double for every normal man. In Ada, one of the characters is murderously described as: ‘Burly, handsome, indolent and ferocious, a crack Rugger player, a cracker of country girls, you combined the charm of the off-duty athlete with the engaging drawl of a fashionable ass.’

The protagonist of Ada, Van Veen, who, with his sexual prowess, ‘had lived up to the ancestral motto: “As healthy a Veen as father has been”’ is a fairly cruel and repulsive (though passionate) animal.

In ‘Wingstroke’, skiing is described with an utterly Tolstoyan defamiliarization: ‘A man sticks a pair of boards on his feet and proceeds to savor the law of gravity. Ridiculous.’ In ‘An Affair of Honor’, the protagonist’s adversary compares himself to an ‘athletic angel’, and, of course, turns out to be a first-rate scoundrel. Elsewhere, he calls the muscles ‘prosaic’.

Véra and Vladimir Nabokov, Berlin/Alamy

In Mary, an early work, he writes, ‘People who shave grow a day younger every morning.’ In Bend Sinister, however, Adam Krug’s ‘morning had been shaveless’, which somewhat revives him.

The heavy Krug, the clumsy Pnin, and the flabby Luzhin are some of Nabokov’s most sympathetic characters. In fact, Krug is even called ‘the only real man’ as well.

In addition, one of the most charming characterizations that Russian prose has ever given a man is infinitely far removed from athleticism: ‘His whole aspect resembling a peaceful toad that wants only one thing—to be left in complete peace in a damp place.’

Nabokov’s famous instruction ‘All my books should be stamped “Freudians, Keep Out”’ is also ambiguous. It can be seen both as a sign of innate mental health and as a fearful desire to be left alone with his mental problems.

I Is for Indrik.

The hero of the novel Glory is a hero in the literal sense, which is rare for Nabokov. A young emigrant plans a chivalrous and deliberately fatal return from Berlin to the Soviet Union, including an illegal border crossing. His name is Martin Edelweiss, but his artist grandmother’s maiden name is Indrikov, and Indrik is a fairy-tale beast found in many mythologies, something between a mammoth and a unicorn. Nabokov thus introduces a heroic-mythological layer to the story (the grandmother also leaves him a watercolor of a fairy-tale forest). According to a legend, Indrik lived near the Nile and killed a crocodile in battle. It is noteworthy that Nabokov’s novel Despair also mentions an ‘eau de Nil dress’.

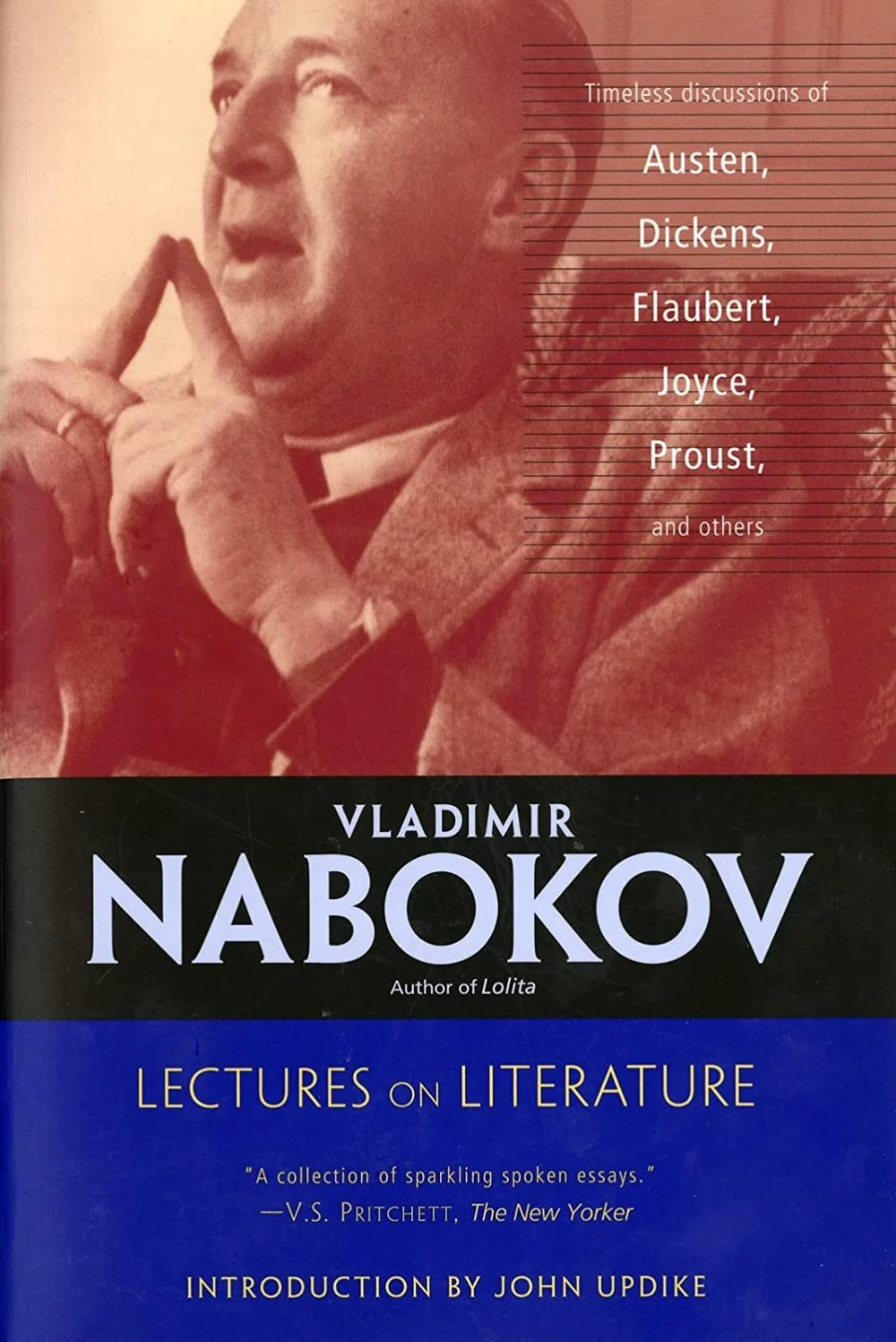

Lectures on Nabokov's Literary History (American edition)/from open access

P Is for Pun.

Nabokov is essentially a funny writer—especially if one understands humour according to his formula: ‘Laughter is some chance little ape of truth astray in our world.’ Nabokov’s stray ape plays with words to the point of exhaustion, elevating to a higher principle what he in ‘Spring in Fialta’ calls a ‘poisonous pun’.

Nabokov sometimes got into trouble for these puns. John Updike, for example, called the style of Ada ‘garlicky puns’, while the brilliant gagger of the Russian emigration Georgy Ivanov even said that Sirin’s stories were ‘vulgar to the point of virtuosity’.

Indeed, Nabokov’s linguistic jokes are innumerable. The title of his largest novel, Ada, is itself a play on words that leaves room for the translator’s imagination (Ada, or Ardor: A Family Chronicle). ‘Transport’ (verb) is understood as ‘transport’ (noun) in The Gift. His plays on language show up in other works like Bend Sinister, with ‘Sesamka’ meaning ‘latchkey’ in Bend Sinister and the clever introduction of Dorianna Karenina in Laughter in the Dark. ‘If I’m a “summer” you’re surely a spring cinquefoil—’ says one of the characters in Mary. ‘Tales’ can be transformed into ‘sales’ in Tyrants Destroyed. ‘The admiral whose fleet is lost in the raging waves’ in a vapid official speech is perceived by the widower as ‘an animal [who] has lost his feet in the aging ocean’. Updike had a point, one must then suppose, looking at one of the jokes in The Gift: ‘Take oneself in hand: a monastic pun’.

Vladimir Nabokoм/Getty images

But it is not even the abundance of puns, but their authorship. As is normal with Nabokov, everything is bifurcated, and both complete fools and the most sympathetic characters (and the writer himself) can make jokes. ‘When some extravagantly praised Kant, others Kont (Comte), others again Hegel or Schlegel,’ — this is the author himself speaking. ‘Not by educators but by educationalists’, ‘traitors, not teachers’— this, too, is Nabokov himself in Lectures on Russian Literature.

The idea of Lolita seems to be defamed and ridiculed in advance by Nabokov in The Gift, where he puts the plot of the future book into the mouth of the most vulgar character. Conversely, in the poignant beginning of the story ‘Ultima Thule’, when the artist Sineusov is talking to his dead wife and unborn child, Nabokov suddenly makes a joke ‘for the sake of an ornate phrase’ that destroys all the pathos. Later in the same monologue, an explanation of sorts appears: ‘Perhaps our whole earthly existence is now but a pun to you, or a grotesque rhyme, something like “dental” and “transcendental.”’

Vladimir Nabokov statue. Lake Geneva, Montreux, Canton Vaud, Switzerland/Alamy

A pun, in Nabokovian terms, is not just a verbal double but a kind of consolation sent from above, a vain attempt to find its letter in the sea of language. After all, as he writes in Bend Sinister, death is but a question of style.

L Is for Luzhin.

Aleksandr Ivanovich Luzhin, partly inspired by the fourth World Chess Champion Alexander Alekhine, is not only the hero of one of his novels but also an archetype of Nabokov’s universe.

Luzhin is the son of a children’s writer, a child prodigy who wants to remain a child, needing care and protection throughout his life. Chess, as the highest form of imagination, becomes that kind of protection for him—chess, where, behind every piece there is a certain musical power.

Traditionally, Nabokov is perceived as a cold chess player and entomologist, a skilled mockingbird, a snob, and an aesthete. But there is another Nabokov, a defender of the little man who can be incredibly sympathetic, a Nabokov filled with pity for the world and its unfortunate inhabitants. A Nabokov who writes about a seventy-year-old woman who dies by suicide at the grave of her recently deceased husband (‘A Letter that Never Reached Russia’). Snobbery and arrogance are Nabokov’s very defenses, who in many of his works raises the question from Gogol’s ‘The Overcoat’: Why do you insult me? The Luzhin Defense takes on different variations in other books: there is also the Pnin Defense, the Cincinnatus Defense, the Krug Defense from Bend Sinister, the Lik Defense from the story of the same name, the Vasily Ivanovich Defense from ‘Cloud, Castle, Lake’, the mediocre Ilya Borisovich Defense from ‘Lips to Lips’, and many other characters’ defenses.

Nabokov and his wife Vera play chess/Carl Mydans/The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

This is true not only of human characters, but of the living world itself. In Ada, they pity a trout boiled alive; in Bend Sinister, they shed tears for a deer that was accidentally hit; in ‘The Admiralty Spire’, they cannot forget the moving tail of a crushed cat. In The Defense, too, there is unbearable tender pity for a thin-legged little donkey with a shaggy belly, brutally beaten in Sicily.

What is there in Luzhin’s world besides chess? Mist, the unknown, nothingness. Luzhin dissolves into it, trying to come up with an unexpected move that would break his opponent’s systematic strategy. But the defense turned out to be wrong, and the hero had no choice but to quit the game, giving rise to one of the most spectacular and complete final sentences in Russian literature.

M Is for Misogyny.

The word itself does not appear in Nabokov’s work, but strictly speaking, it is easy to use the name of any of his flawed heroines instead—Martha from King, Queen, Knave; Marthe from Invitation to a Beheading; the smashing, full-bodied Matilda from The Eye; and, of course, Margot from Laughter in the Dark, with her ‘pale, sulky, painfully beautiful face’. Only Mary from the novel of the same name stands out as a symbol of Russia’s lost purity.

Nabokov wrote his early work under the pseudonym Sirin, the embodiment of the unhappy soul, a bird of paradise with a woman’s head. In his prose, however, these female heads often serve as messengers from directly opposite spheres.

In the novel Bend Sinister, the hero has a nightmare: a woman is undressing, and she’s not taking off only her clothes and necklaces—she removes her head, the rings together with the fingers, and the slippers together with the toes. Such male nightmares overwhelm Nabokov’s prose (he is not ceremonious with men either, but we will talk about that when we get to the letter X).

Dimitri (centre) and his father Vladimir Nabokov (1899 - 1977)dining out after Dimitri's debut as an opera singer at the Communale Theatre, Reggio Emilia, northern Italy. Vladimir Nabokov is the author of 'Lolita'/Getty Images

The women in his texts are filled with ‘innocent dullness’, they smell of vulgar perfume, cannot think of their speech without diminutive suffixes, suffer from gas, whisper loudly at the movies, squeak thinly in bed, laugh at the wretched chimpanzee in the circus, and, of course, cheat incessantly. And the process is described in the most vile terms (‘Little Marthe did it again today’, or ‘the little woman needs something to amuse her’). Even the act of bestiality is briefly mentioned in The Gift, with female participation, of course.

Nabokov is considered by some to be almost a pornographer, and yet he is one of the most squeamish writers when it comes to sex. Only Nabokov could mention ‘the … smell of stale femininity’ (in Transparent Things) and recognize the wickedness of ‘putting her hand to the back of her chignon’. In Mary, he writes about sex: ‘... such filth—and yet delicious’. Also in Mary, he writes, ‘... he had possessed Lyudmila, and at once it had all become utterly banal.’ Elsewhere, Nabokov explicitly calls sex a procedure. It even concerns Luzhin, a character who is not of this world: ‘“A Russian baba,” said Luzhin with relish and laughed.’ This is to say nothing about ‘the Haze woman’. Nabokov, after all, said quite sensibly: ‘Sex as an institution, sex as a general notion, sex as a problem, sex as a platitude—all this is something I find too tedious for words. Let us skip sex.’

‘Every sentence of yours buttons to the left,’ the narrator of ‘The Admiralty Spire’ pejoratively says about a supposed woman composing under a man’s name. The same story emphasizes the ‘ill-tempered, dull expression of her eyes’. The apotheosis could be the story ‘Revenge’, whose hero feels such hatred for his completely innocent wife (he mistook the ghost of a dead young man for her lover) that when choosing her torture, he cannot even decide on the most brutal one, but delights in the story of a woman turned into a worm.

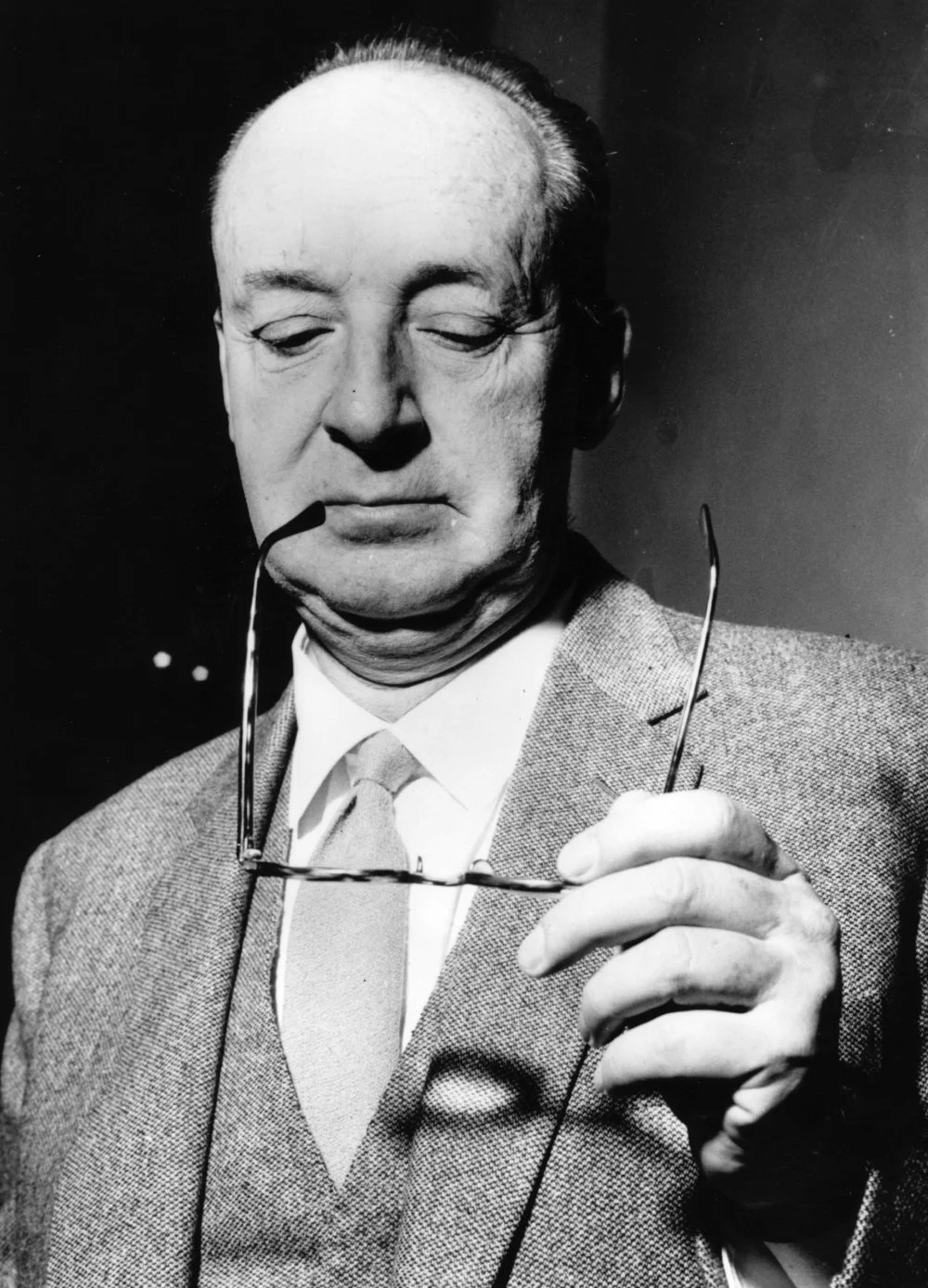

Vladimir Nabokov as Child. 1929/Getty Images

But it is always ardor, however pathological and deadly, that is the subject of Nabokov’s research and, in a sense, his pride. It is not for nothing that this word forms part of the title of Ada. His dispassionate and good characters are always dull and impersonal. We feel nothing for Ganin, who confesses that he was ‘absurdly chaste’, ‘living as [he] was and waiting’, and finally fell out of love with his Mary. We scarcely feel anything for Godunov-Cherdyntsev, who is ‘incapable of giving his entire soul to anyone or anything.’

Even the character of Nabokov’s best love story, ‘Spring in Fialta’, seems criminally sluggish, compared to his incomparably more vivid lover Nina, while his feeling to her is similar to a typical infantile male reverie: ‘Again and again she hurriedly appeared in the margins of my life, without influencing in the least its basic text.’ But those Nabokov characters who are filled with probably villainous but real passions—Van, Albinus, Humbert Humbert, et cetera— stick in the memory.

H Is for Hope.

One of the most unexpected parts of Ada, otherwise full of chunky surprises, is when the characters have a meal at a Russian restaurant and hear the loose translation of Bulat Okudzhava’s ‘Sentimental March’:

Nadezhda, I shall then be back

When the true batch outboys the riot…

Nabokov had translated the full text of the song before the novel was published; unlike the sneering Ada version, that one was quite faithful. It was called ‘A Sentimental Ballad’ in his translation:

Speranza, I’ll be coming back

The day the bugler sounds retreat,

When to his lips he’ll bring the bugle,

And outward his sharp elbow turn.

Speranza, I’ll remain unharmed:

The clammy earth is not for me,

Because for me are your misgivings

And the kind word of your concern.

Okudzhava, in his turn, as reported by witnesses, read Lolita back in the 1960s. If we’re pursuing the extremely unexpected chain of Nabokov’s connections with the Soviet genre of ‘bard’ songs, it is perhaps not Okudzhava but someone like Vladimir Vysotsky, a popular singer-songwriter from the same years, who influenced him. For example, the song ‘The One Who Was with Her Before’ matches the brutally jealous nature of Ada’s protagonist.

It would also be instructive to recall that the name of the ship that took the escaping Nabokov family to Constantinople was Nadezhda—meaning ‘hope’.

The second part of the Vladimir Nabokov's ABCs you can read here.

The Nabokov Family. Vladimir Dmitriewitsch, Elena Ivanovna, Maria Ferdinandovna with children. Private Collection/Getty Images