Soviet cinema, like the broader Soviet system, was strictly hierarchical. Moscow, promoting Russian cinema as the standard for the entire Union, showed little interest in fostering national film industries, leaving their development largely dependent on local initiatives. Moreover, cinema remained under direct central control longer than many other spheres, increasing pressure and imposing stringent demands on directors. Even during a period when any depiction of national life was rigorously monitored and the narrative of ‘integrating the Kazakh people into the global community solely through Soviet authority’ was enforced, some directors offered alternative interpretations of the nation’s spiritual and cultural roots. Researcher Assiya Issemberdiyeva highlights how the history of Kazakh cinema in the USSR became deeply politicized.

In film studies, according to the popular ‘auteur theory’, directors are regarded as full-fledged creators of their works. In the USSR, however, cinema was perceived not as an art form but as an instrument of political influence. Creative teams were under the complete control of the state at every stage of production—from the approval of the theme to the film’s final edits. In the Soviet system, talent was turned into an ideological resource, while ‘pure’ artistic expression was considered useless and unnecessary. Many internationally acclaimed directors, such as Dziga Vertov and Mikhail Slutsky, were sidelined from their work on the flimsiest of grounds.

“A Poem of Love” (1954). Directed by Shaken Aimanov / Open sources

Locked within rigid boundaries and intimidated by the system, directors could not openly oppose the totalitarian order. Although the first feature film by a Kazakh director—Shaken Aimanov’s Poem of Love—premiered only in 1954, by the 1960s, films that subtly conveyed a message of resistance to Soviet ideological control had begun to emerge.

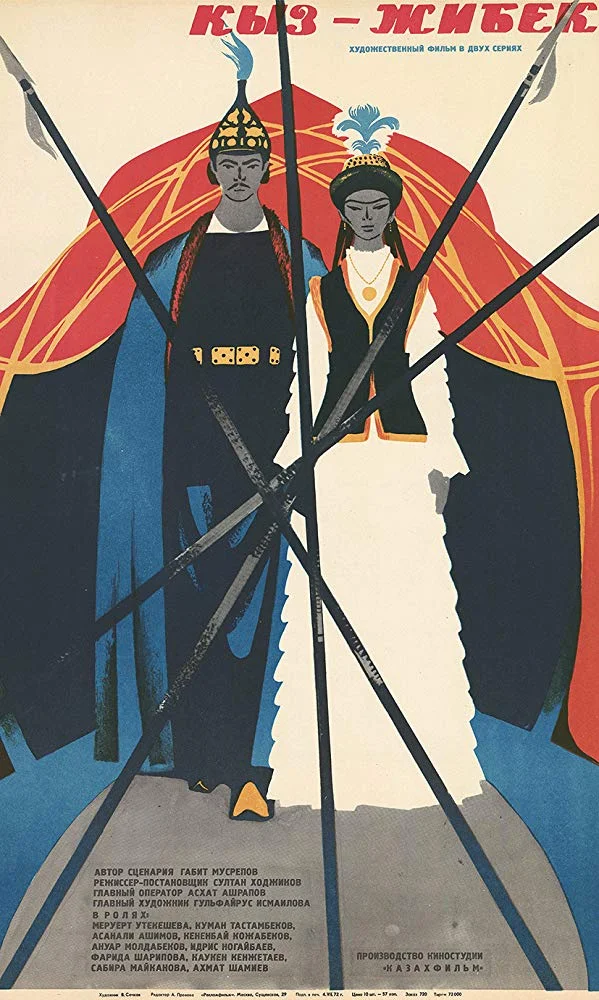

“Kyz-Zhibek” (1971). Directed by Sultan-Akhmet Khodzhikov / Open sources

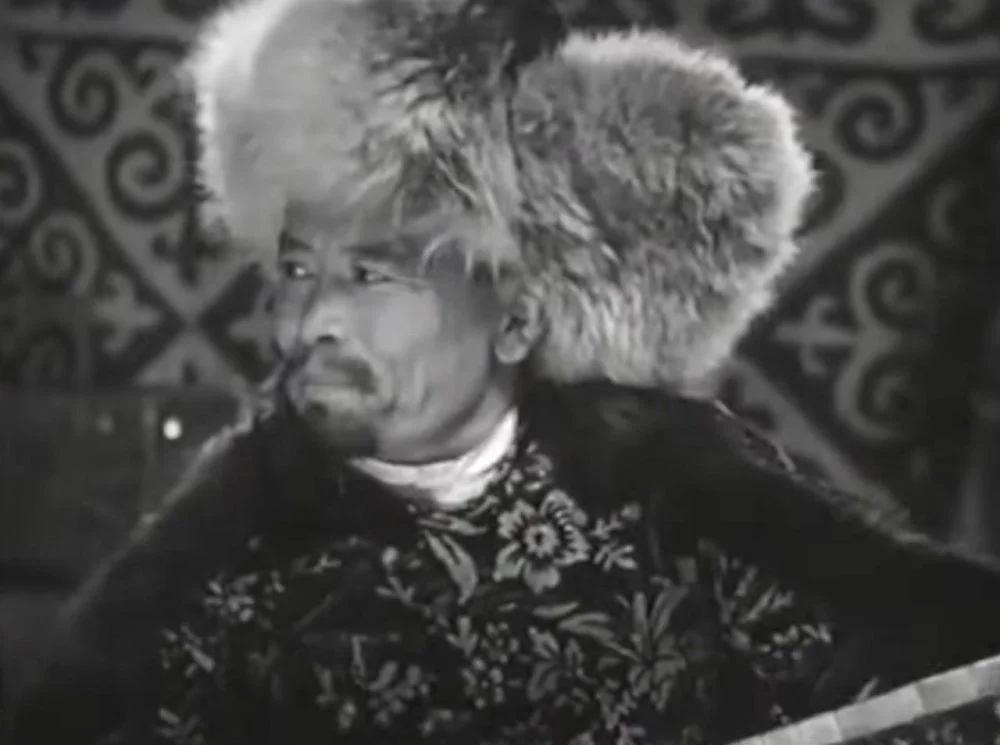

Even under intense ideological pressure, works appeared that did not fit the prevailing ideological narrative. One such example was Qyz Jibek (Қыз Жібек in Kazakh; 1971) by the director Sultan-Akhmet Qojykov. At first glance, the film seems like a love story, but in reality, it examines much deeper themes. However, before speaking of the ‘Golden Age’ of national cinema, it is important to recall who stood at its origins and the circumstances in which the Kazakh film studio was established.

The First Kazakh Film Manager

From the 1930s onward, having taken control of national policy, the Soviet authorities fully centralized the film industry in Kazakhstan. Most large and small studios in the USSR and the union republics were shut down. Film production came under the direct control of Moscow. It was subordinated to central bodies—first to the Chief Directorate of the Film and Photo Industry (abbreviated as GUKF) under the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR (1933–1936), and then the All-Union Committee for the Arts (1936–1938). In subsequent years, the main regulatory body repeatedly changed its name and structure, but control of the industry remained consistently centralized.

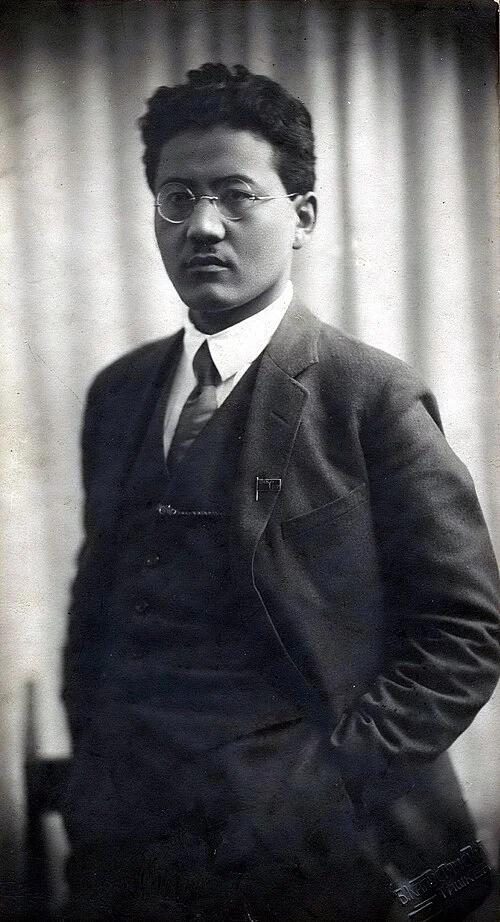

Turar Ryskulov / Wikimedia Commons

It was during this period that national cinema finally became a political issue. The creation of films, the training of directors, and the approval of projects are often described either as the exclusive will of Moscow or as some kind of natural process. However, if everything had truly depended only on the center, cinema in Central Asia would simply have lost all meaning. Only a few films were granted screen time, while local initiatives were constantly suppressed by Moscow’s interests, leaving the regions on the periphery. Films and film studios were especially scarce among peoples without their own union republic.

In the history of Kazakh cinema, the contributions of those republican leaders who fought to restore cultural institutions and values destroyed by Moscow’s policies often go unnoticed. The first feature film studio in Kazakhstan was the Kazakh branch of Vostokkino, which was established in 1929. Vostokkino was created by Turar Ryskulovi

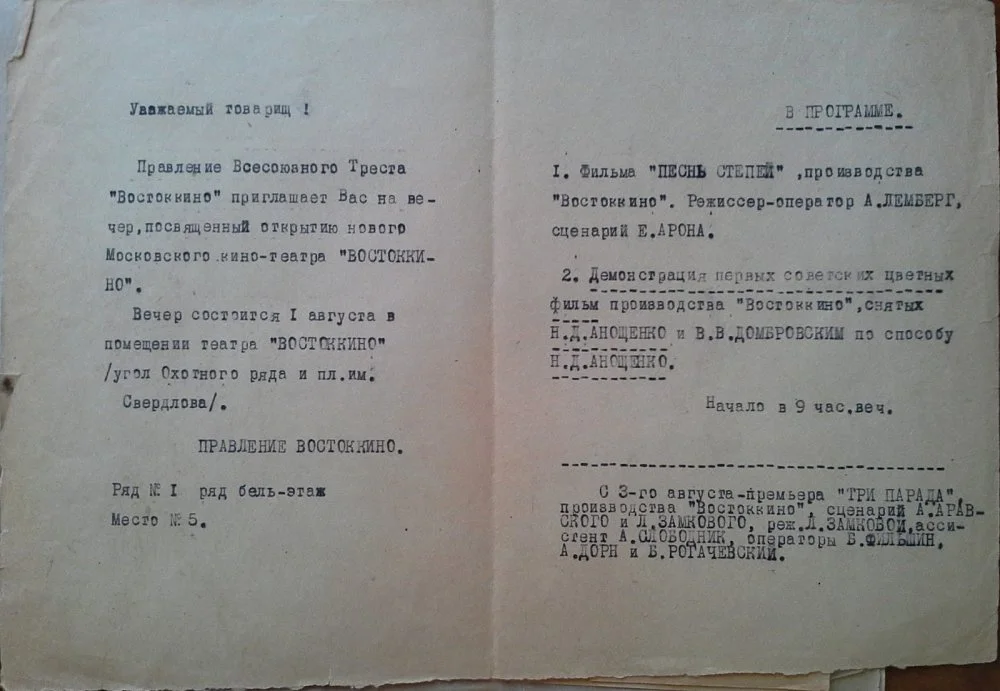

Invitation ticket for the opening of the “Vostokkino” cinema, 1 August 1931 / Wikimedia Commons

The association included representatives from more than ten regions—from Tatarstan and Dagestan to Yakutia—and was funded by local governments. However, the Kazakh branch of Vostokkino lasted only until the end of 1931. The reason was simple—in October 1931, the USSR's New Economic Policy finally ended, and private trade ceased. Vostokkino lost its financial independence and was reorganized into a production trust. In response, Ryskulov sent a letter to Stalin and Kuybyshev, expressing his categorical disagreement with this decision:

Sovkino constantly interfered with the work of Vostokkino. For example, during the filming of Turksib, Sovkino refused to provide equipment, and Vostokkino was forced to source it from private owners. From the moment Sovkino was created, it did not train a single film specialist from among the local nationalities. Vostokkino, on the other hand, managed to train quite a number of specialists in a short time. If the national republics are restricted in their participation in the all-Union film organization, their cultural and political interests will not be truly protected.

Indeed, soon the local personnel working at the Kazakh branch of Vostokkino met a tragic fate. Cinematographer Eskendir Tynyshbaev—the son of the political figure Mukhamedjan Tynyshbaev, who was executed in 1937—himself became a victim of repression. The screenwriters Ilyas Jansugurov and Beimbet Mailin, as well as Ryskulov, who can rightfully be considered the first domestic film manager, were executed by firing squad.

Postage stamps of Kazakhstan: Beimbet Mailin, Ilyas Zhansugurov, Eskendir Tynyshbaev, Turar Ryskulov / Wikimedia Commons

After the dissolution of Vostokkino, no independent film studios were established in Kazakhstan until the 1940s. During this time, only a few films were released, produced by central studios and supported by local communists. Among them were Amangeldi (1936) and Raikhan (1938).

Ondasynov, Shaiakhmetov, Tajibayev: The Struggle for a Kazakh Film Studio

Even after the formation of the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) in 1936, local communists continued to literally flood Moscow with requests to make films on Kazakh subjects and to establish their own film studio. Screenwriting competitions were regularly held in the republic, the best works were selected, and funds were allocated to train film professionals in Moscow. However, not all of these plans could be realized. Thus, in 1939–1940, twenty-three Kazakh students were admitted to VGIKi

Although the contributions of the party leaders of that period—Nurtas Ondasynov, Jumabai Shaiakhmetov, Tölegen Tajibayev, and Gabdolla Buzyrbaev—often remain in the shadows, it must be acknowledged that the creation of the Kazakh film studio was, above all, the result of their persistent, long-term efforts.

Nurtas Ondassynov / Open sources

The Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Kazakh SSR, Nurtas Ondasynov—who had been steadily pressing Moscow since the late 1930s to establish a film studio—met with Ivan Bolshakov, head of the Film Committee, on 20 June 1941, to discuss the matter. Bolshakov expressed full support, but two days later, Germany attacked the USSR. And on 28 July, Bolshakov himself asked for assistance: film workers and equipment were being evacuated to Almaty, and support was needed. In August, employees of Lenfilmi

Evacuation During the War Years and Discrimination against Kazakhs

On 12 September 1941, even before the arrival of specialists from Lenfilm, the Kazakh Communist Party and the Council of People’s Commissars adopted Resolution No. 762, officially establishing the Alma-Ata Film Studio. In fact, this date is still marked as the Day of Kazakh Cinema.

The persistence of Party Deputy Shaiakhmetov and Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars Ondasynov was guided by a clear conviction: the central studios had to understand that they were no longer in just another corner of the RSFSR, but that they were in Kazakhstan, and that the Kazakhs’ aspiration to create their own national cinema deserved recognition. Making use of the arrival of specialists from Moscow and Leningrad, they ensured that the resolution included a commitment to produce films on Kazakh themes and to train local personnel.

The building that housed the film pavilions, Almaty. 1941 / Open sources

Ivan Bolshakov perceived this resolution as a direct threat, fearing that Lenfilm and Mosfilm might slip out of his control. In response, he hastily established the Central United Film Studio (abbreviated as TsOKS), merging Mosfilm, Lenfilm, and the Alma-Ata Film Studio. In essence, this was an attempt to deprive the Kazakh leadership of the ability to influence film production. Mikhail Tikhonov, one of Bolshakov’s trusted film managers, was appointed director of the new studio. However, the Kazakh leaders did not back down: they secured the appointment of Sergali Tolybekov, an economist and vice-rector of the Almaty Pedagogical Institute, as deputy director of TsOKS. He was tasked with curating national subject matter and training personnel.

And although the leadership of TsOKS promised that in 1942 they would produce one feature-length and two short films, they were in no hurry to begin work. Moreover, they were reluctant to accept Kazakh specialists and soon moved on to open discrimination. Deputy Director Tolybekov was swiftly removed, and pressure soon turned to Qabysh Siranov, a VGIK graduate and screenwriter who had taken his place. Outraged by these developments, Siranov addressed the issue bluntly at a film studio meeting in 1942, declaring:

At a recent meeting with Comrade Ondasynov, Fridrikh Markovichi

Fed up with the constant disregard for their initiatives, in 1942, Kazakh officials once again demanded complete control over the republic’s cinema. They proposed establishing an independent film committee, subordinate to the Council of People’s Commissars and responsible for managing all film institutions. In mid-January, at a meeting chaired by Deputy for the Arts Tölegen Tajibaev, Kazakh representatives presented a detailed justification for this initiative. However, Tikhonov immediately opposed it: he promptly reported the ‘rebellion’ in Kazakhstan to Bolshakov and managed to shut down the project at an early stage.

“Songs of Abai” (1946). Directed by Grigory Roshal / Open sources

Although the Alma-Ata Film Studio was officially established in 1941, it was far from being a ‘gift from Moscow’ given out of goodwill. It was the result of persistent lobbying by local communists—and not always successfully. It’s important to remember that, contrary to popular belief, the Soviet studios evacuated to Kazakhstan at that time did not bring the republic any special advantages. The local authorities had to fight for every film on Kazakh themes and for every Kazakh specialist.

As a result, during TsOKS's period of operation, no feature-length film on Kazakh themes was produced. However, after Mosfilm and Lenfilm returned to the center and the Alma-Ata Studio continued to operate independently, films such as Songs of Abai by Grigory Roshal (1946), Dzhambul by Efim Dzigan (1952), and Poem of Love by Shaken Aimanov (1954) began to appear. Even so, obtaining approval for each such film turned into a cultural and political battle, involving hundreds of letters and endless trips by local officials to Moscow and back.

“Jambul” (1952). Directed by Yefim Dzigan / Open sources

This relentless struggle continued into the 1960s–1970s. Each theme had to be defended separately, and the projects themselves passed repeatedly through Moscow’s censorship, both at the script stage and after filming. It was precisely then that such ‘sensitive’ issues as national history, culture, and the portrayal of Kazakhs and Russians on screen were subjected to especially close scrutiny and multiple revisions. Even ignoring production challenges, no national film in the Soviet era escaped ideological scrutiny. Tragically, many scenes deemed ‘dangerous’ by Moscow were omitted and never reached audiences.

Why Was Qyz Jibek Cut to Pieces?

In this context, the story behind the making of Qyz Jibek by Sultan-Akhmet Qojykov, a true pioneer of Kazakh cinematography, is fascinating. In 1967, the head of Kazakhfilm, Kamal Smailov, went to Moscow to defend the annual production plan. When one of the three screenplays he proposed was rejected, Smailov received permission to replace it with another. He recalled Gabit Musrepov’s work Aqqu (The Swan), a novella written back in 1944. It had been kept in the studio archives and was once recognized as ‘the best film novella on a Kazakh theme’. The work was based on the epic Qyz Jibek.

Upon returning to Almaty, Smailov immediately called Musrepov and asked him to write a film script based on Aqqu and the play Qyz Jibek. The writer completed the script within a month.

Film poster for “Kyz-Zhibek”, 1970 / Wikimedia Commons

It’s hard to say whether this was a lucky coincidence or proof that the truth cannot be hidden, but the work, which had been sitting untouched for over twenty years, unexpectedly got its chance and went into production.

In Soviet Kazakhstan, filmmaking was not just the product of a studio’s work; it involved the participation of all relevant state structures. An excerpt from the script was published in the newspaper Leninshil Jas, a major casting call was announced on 1 January 1968, and a large expedition was organized to gather props. Costumes and jewelry were crafted from expensive fabrics and metals.

The film’s costs ultimately exceeded the planned budget. Although documentation specified 2,700 meters of film stock, Sultan-Akhmet Qojykov shot a two-part film totaling 3,700 meters. This sharply strained relations between the director and the studio: during the production, Qojykov received around twenty official reprimands. Instead of the promised 850,000 rubles, the studio initially received only 650,000, and it was only after Kunaev’s intervention that an additional 250,000 rubles were allocated. Even so, these funds were still insufficient to complete a film of such epic scale. As a result, the production team—and above all Qojykov himself—ended up owing the state. By 1971, when the director received a state award, he handed over his prize to the studio to partially repay this debt.

Although the studio’s artistic council ultimately approved the film after lengthy debates, with the support of culture minister Ilyas Omarov, the State Committee for Cinematography in Moscow subjected it to severe criticism. As a result, the film was so heavily ‘reworked’ that roughly thirty minutes were cut from the original three-hour version. Among the deleted scenes was the battle between the Kazakhs and the Kalmyks, which had taken an entire month to shoot on the banks of the Ili River. Rumor had it that the official reason was that the Kazakh army appeared ‘too large’. Even in 1970, during the relative ideological thaw, Moscow would not allow Kazakh history to be shown as a story of political unity with a strong national army. The film was also condemned for ‘overly embellishing and romanticizing the past era’.

Ilyas Omarov / Open sources

For the first time, Grigory Roshal’s film Songs of Abai faced such harsh criticism. Afterward, most films about the past, wary of repeating this fate, aimed to depict the ‘feudal era’ in the least flattering light. For instance, Yefim Dzigan’s Jambyl portrayed pre-Soviet Kazakhs not as people living in traditional yurts, but as a ragged group of poor folk dwelling in makeshift military tents.

Against this backdrop, Qyz Jibek stands out as a vivid celebration of traditional Kazakh life in the Soviet era. The film’s artistic vision honors national culture and sends a clear message to viewers: ‘Never be ashamed to call yourself Kazakh.’

Love or National Tragedy?

The battle scene that Qojykov filmed was crucial. In his vision, Musrepov’s script became not a love poem, but primarily a story about Kazakh statehood. It’s no coincidence that the film’s title, Qyz Jibek, appears on screen in sequence: first in Old Turkic runes, then in Arabic script, and only at the end in Cyrillic. This deliberate choice reflects the director’s nod to the deep spiritual, cultural, and civilizational roots of the Kazakh people—roots that extend far beyond those acknowledged by Soviet ideology.

Let’s turn to the film’s opening. The first shot presents the exclamation ‘Iä, aruakh!’ (‘Yes, spirits of the ancestors!’) alongside blood splashed across the ground. In the following brief sequences, we see flowing water dyed red (‘blood running like a river’), a horse left without its master, exhaling its spirit. Swans with blood-stained wings, horse hooves smeared with blood, a spear dragged along the ground, a mourning nomadic camp, and the trace of a swan left in blood on the earth soon appear. As the camera continues its movement, a discarded kazan (cauldron), a shattered shañyraqi

What is conveyed here is not so much a tragic love story as the profound grief of an entire people. These visual metaphors translate the literary motifs of the heroic epic tradition and Abai’s poetry into cinematic language, serving as a genuine expression of the national aesthetic code.

Another reason to view the theme of Qyz Jibek as an expression of national revival lies in the contrast between Tölegen and Bekejan, the male protagonist and the male antagonist. Tölegen’s superiority over his rival is expressed not only in his passion but also through his insight. At the beginning of the film, when Bekejan boasts of his supposed victory, his arrogance is cut short by Tolegen’s words: ‘It is not that we cannot fit into this boundless steppe—it is that we cannot live together in it.’ Tölegen condemns Bekejan not for his belligerence as such, but for the fact that, relying solely on brute force, he conducts raids against another Kazakh clan.

Initially, Tölegen’s father, Bazarbai, the influential head of the Jağalbaily clan and owner of vast herds, sends his son to attack Syrlibai’s auli

In this way, Tölegen’s mission in the film embodies the idea of political unity, a call to abandon internal strife and unite against an external threat. Even setting out on his final journey, he mourns not so much for his bride as for his people. His death, shown against the backdrop of the balbals, ancient Turkic stone effigies, reinforces the notion that internal discord is an age-old, historically recurring tragedy for the nation.

Thus, the main storyline of Qyz Jibek is not a celebration of love, but a tribute to the unity of the three jüzes, a reflection on national history, and a return to traditional culture, depicted in a lofty, almost epic manner. Although the excised scenes are considered lost, it is evident that in portraying the war between Kazakhs and Kalmyks, Qojykov was subtly alluding to events of his own era. As the son of Qoñyrqoja Qojykov, a figure of the Alash movement who survived exile only to be later executed, Sultan-Akhmet was well aware of the repressions, internal conflicts, executions, and betrayals that befell the Kazakh intelligentsia during the Soviet period.

The First Films about Famine

During an era when artistic works were expected to be ‘national in form, socialist in content’, Qojykov deliberately sought to create films grounded in authentic national themes, developing a distinctive cinematic language. His approach was likely shaped by his training at VGIK under the Ukrainian master Alexander Dovzhenko, from whom he learned to express the national essence through a poetic lens. Unlike his contemporaries, Qojykov was the first to courageously depict famine on screen. Although We Are from Semirechye (1958) and Chinara on the Rock (1965) ostensibly depict the 1918 famine, unrelated to Soviet authority, these portrayals can be interpreted as symbolic representations of the devastating famine of 1930–1933, a subject that was strictly censored in the USSR.

“We Are from Semirechye” (1958). Directed by Sultan-Akhmet Khodzhikov, Alexey Ochkin / Open sources

At first glance, Chinara on the Rock appears to be an adaptation of Auezov’s work Jas Tülek (The Young Generation). The story of how two young men meet a girl named Aisulu is shown from two perspectives. Yet, essentially, the narrative is not only about the real Aisulu and the two protagonists, but also about the legendary, idealized image of Aisulu that continually emerges in their conversations. The psychological tragedy of the heroine—a girl forced to sell what she holds most dear during the famine—is conveyed in a poetic manner. The heroine symbolizes not only the nation's physical suffering but also its cultural devastation.

“Chinara on the Cliff” (1965). Directed by Sultan-Akhmet Khodzhikov / Open sources

Similarly, the brutality of the ‘Whites’i

Qojykov’s films made before and after Qyz Jibek did not receive wide recognition. After the release of Qyz Jibek, he went nearly fifteen years without directing another film. The scripts he wrote during this time, including an epic biographical project on Al-Farabii

“Know Ours” (1985). Directed by Sultan-Akhmet Khodzhikov / Open sources

Consequently, in the film depicting ‘the friendship of Kazakhs and Russians’, the Kazakh wrestler was gradually pushed out of the central protagonist role. Following the center's directives, the film became a story that emphasized Poddubny’s superiority rather than Qajymuqan’s. This was Qojykov’s final and most grueling work.

“An Anxious Morning” (1968). Directed by Abdolla Karsakbayev / Open sources

Beyond his artistic mastery, Qojykov’s internal resistance to Soviet policies can be regarded as genuine heroism by the standards of that era. Similar heroism is evident in several Kazakh films made during the Khrushchev Thawi

“Atameken” (1966). Directed by Shaken Aimanov / Open sources

Thus, the key to the ‘Golden Age’ of Kazakh cinema lies precisely in this very spirit of resistance—the courage to defy official ideology and keep the true voice of the nation alive.

In preparing this material, data from the Central State Archive of the Republic of Kazakhstan, the Archive of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan, and Bolat Nusimbekov’s documentary film Sultan Khodzhikov’s War and Peace (Kazakhfilm, 2013) were used.