New Year celebrations vary across cultures and are celebrated differently around the world. While 1 January, based on the Gregorian calendar, has become the most recognized date for new year celebrations, billions of people still observe the holiday according to lunar or lunisolar calendars.

But what about medieval Baghdad, one of the most ethnically and religiously diverse metropolises of its time? How did its inhabitants mark the arrival of the new year? Let’s explore the unique traditions of this vibrant metropolis.

The modern idea of ringing in a new year based on 1 January is a relatively specific tradition, particularly significant in post-socialist regions. In much of the Christian world, Christmas holds greater importance, as is reflected in its influence on popular culture. During the Middle Ages, however, societies were far more fragmented, with local traditions and festivals holding greater importance. In medieval Europe, for example, these could include feast days honoring local saints.

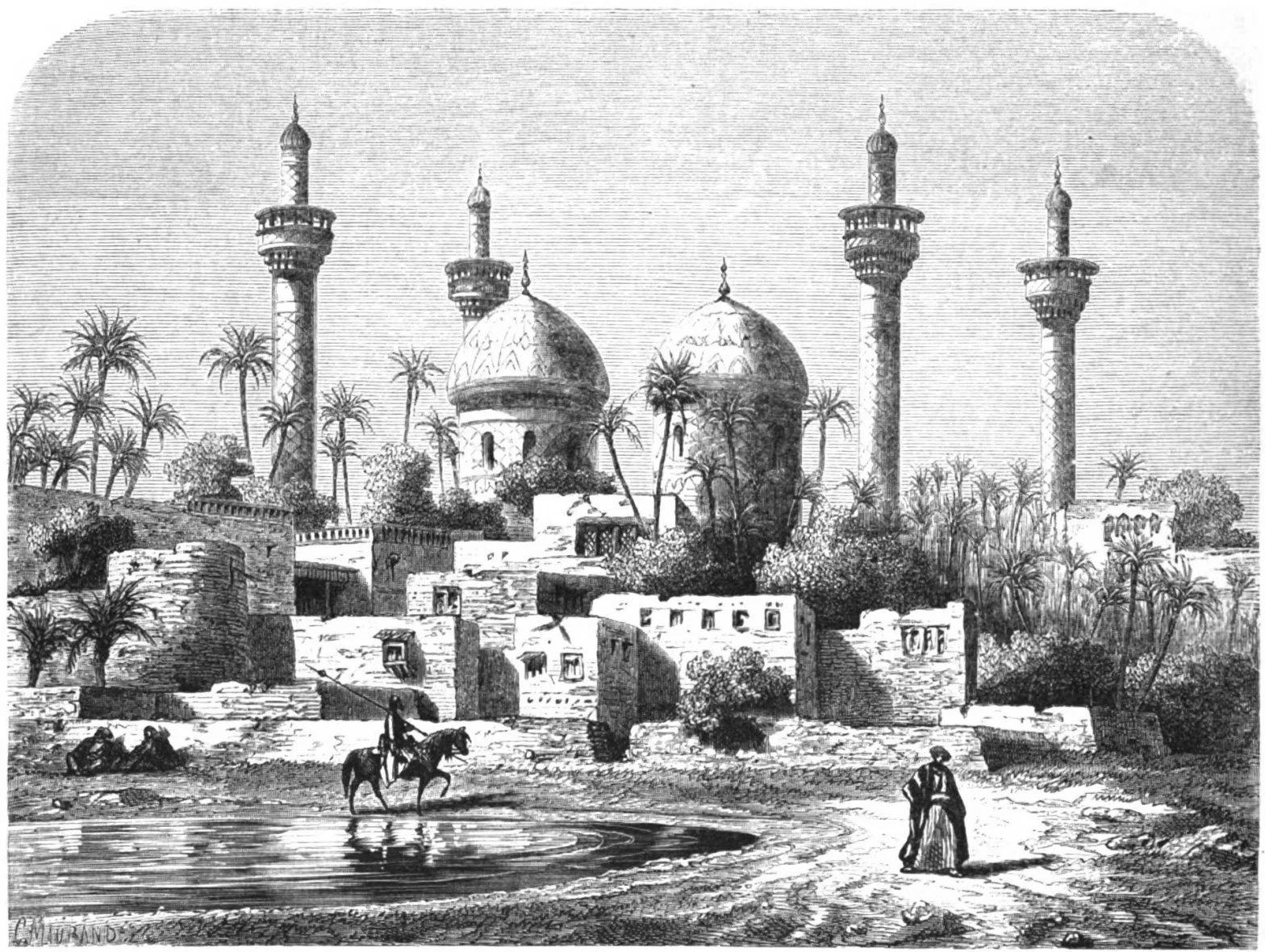

River Tigris in Baghdad. From anthology of poems by various authors, created in Shirvan (Samakha), North Iran, dated 1468/Wikimedia Commons

The medieval Middle East, and Baghdad in particular, is notable for uniting a vast territory where Muslims, Christians, and Jews coexisted. And that’s just regarding religion—there were many more ethnic groups: Arabs, Jews, Greeks, Syrians, Copts, Persians, and others. From the eighth to tenth centuries, Baghdad, the capital of the Arab Caliphate, brought together these diverse peoples and faiths, serving as an early example of unique globalization.

People living there freely observed their traditions, and the authorities did not interfere with them. Moreover, Muslims often participated in Christian celebrations, while Zoroastrians joined Muslim festivities. This inclusivity extended to New Year celebrations, meaning the average Baghdadi might enjoy festivities for three different new years in one year.

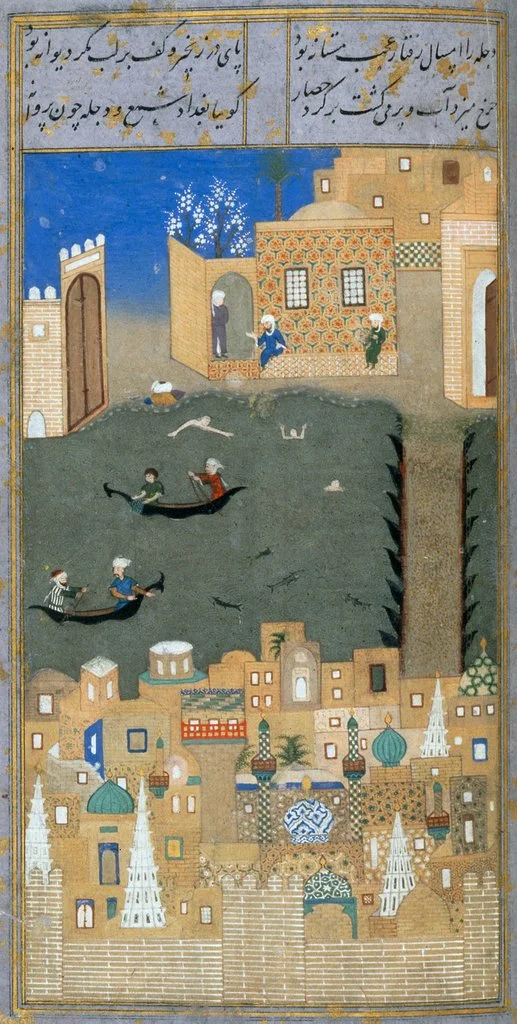

Nestorian (Assyrian) Christian family making butter, Mawana, Persia/Wikimedia Commons

To add even more variety, one of these celebrations occurred at a different time each year, on the first day of the Islamic calendar year, determined by the lunar calendar, which is not tied to the twelve solar months but follows the shorter lunar months. However, for Muslims, it was not considered a particularly significant holiday.

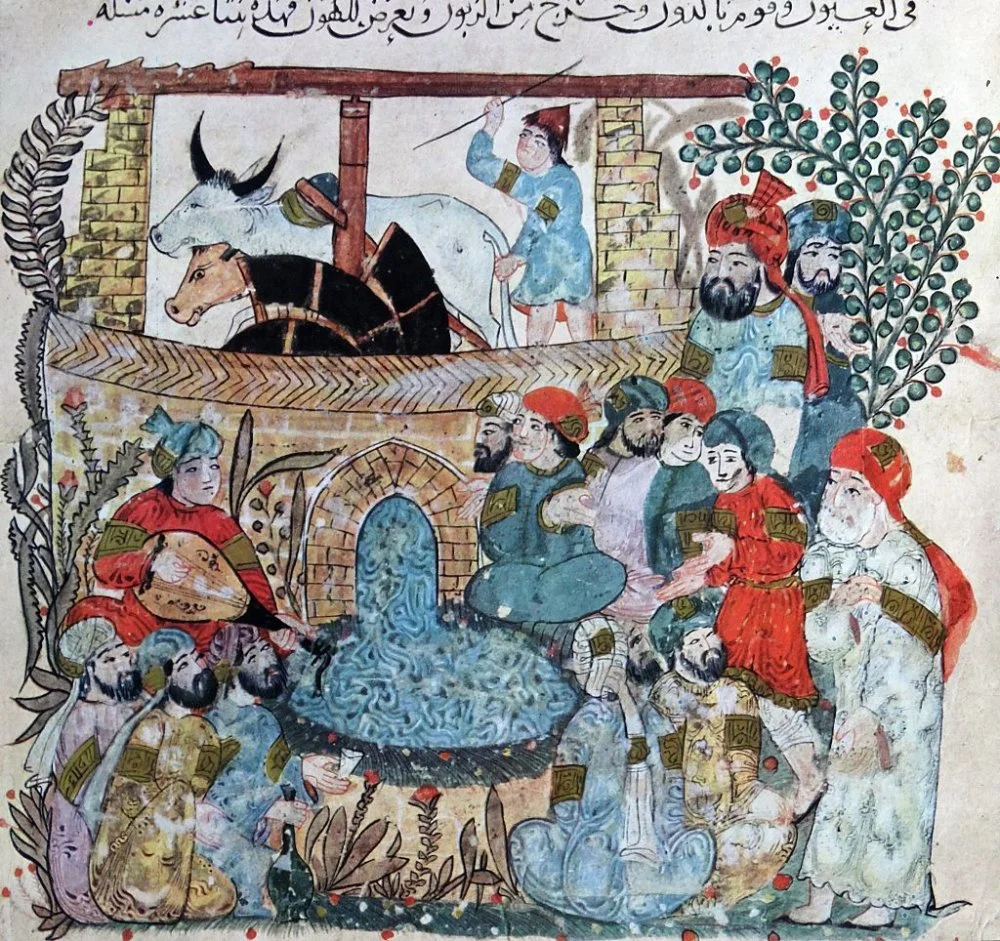

Maqamat of al-Hariri. Artist Abu Zayd al-Saruji Procession at the end of Ramadan. 1237AD/Bibliothèque nationale de France/Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

The second celebration for New Year in Baghdad was the Iranian New Year, Nowruz, which eventually spread to the Turkic world. It coincided with the Syrian New Year, which was marked by the spring equinox taking place on March 21–22.

Mirza 'Ali The Nasser D. Khalili.Preparations for the Nauruz feast. Barbad the Concealed Musician. Collection of Islamic Art/Wikimedia Commons

The Copts (Egyptian Christians) celebrated their new year at the end of August. Although the Copts were far more numerous in Egypt than in Baghdad, their holidays were known there as well. Interestingly, the name of the Coptic New Year, Nayrouz, is phonetically similar to the Iranian Nowruz. Both Persians and Copts had a tradition of sprinkling water on each other, as water was believed to ward off illness. Despite attempts in the East to ban this practice as contrary to Islamic religious norms, it continued to persist. People sprinkled water by hand or used silver or copper tubes.

Maqamat of al-Hariri. Abu Zayd and his listeners at a literary gathering in Baghdad. 1237AD /Bibliothèque nationale de France/Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

These celebrations were considered almost official state holidays. The caliphate's historical financial records include expenses for various new year celebrations. On the eve of the Islamic New Year, caliphs in the capital distributed various figurines as gifts, including red roses made of ambergris of the finest varieties sourced from southern Arabia. Ambergris was an extremely valuable material prized for its long-lasting, exquisite fragrance and used in high-end perfumes and luxury incense.

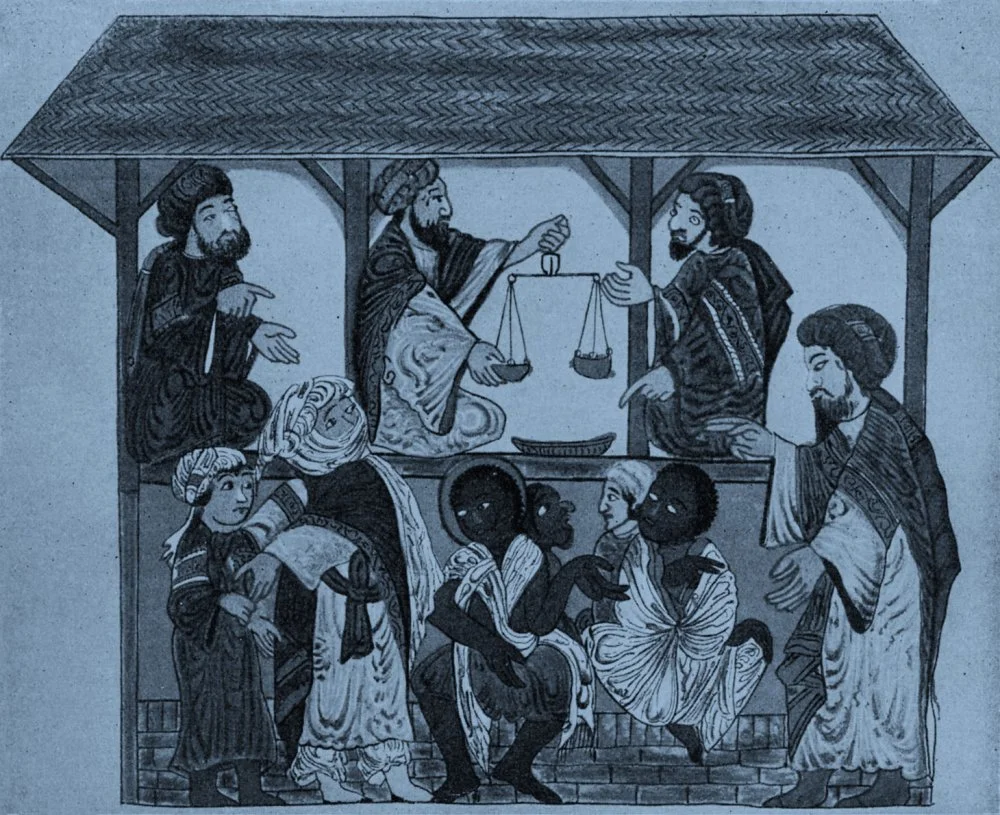

Bazaar life in Baghdad, Iraq - from the Maqamat of al-Hariri/Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images

The tradition of rulers giving gifts extended beyond Baghdad. The Samanids (875–999) in Bukhara paid their soldiers the value of their summer uniforms, while the Fatimids (909–1171) in Egypt gifted clothing and food. Courtiers and subjects exchanged gifts among themselves and presented offerings to the caliphs.

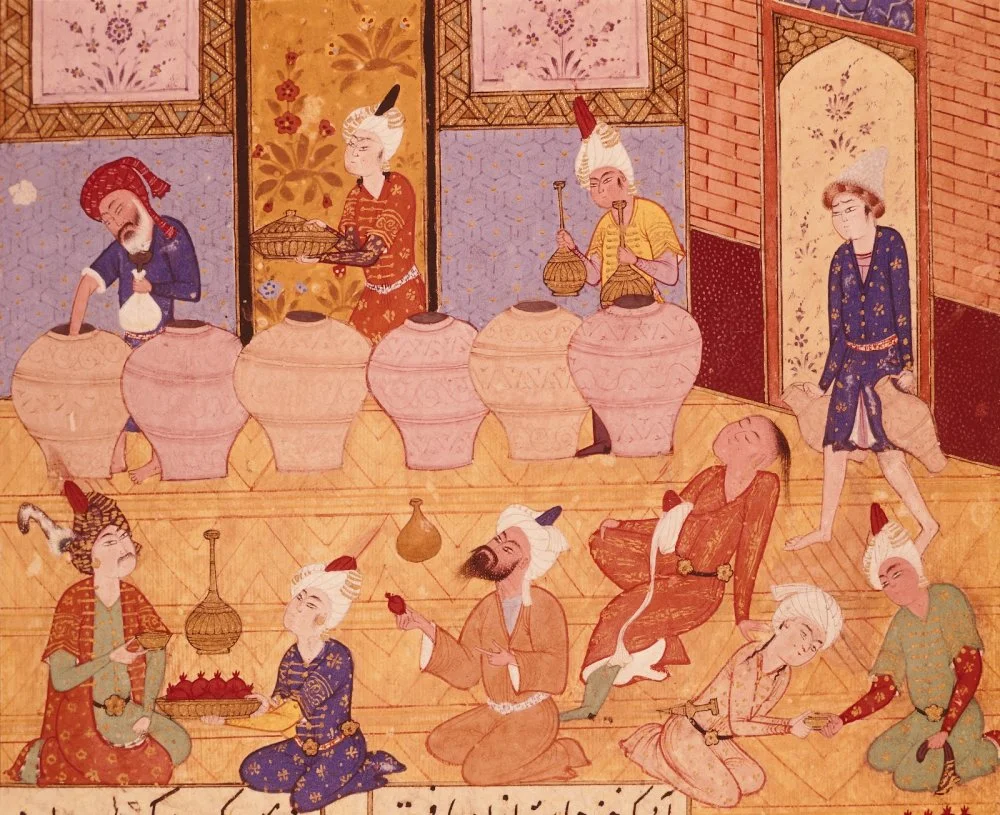

Scene at a banquet, illustration from the Lyrics of Hafiz, Persia 16th Century/DeAgostini/Getty Images

In Baghdad, new year celebrations included masked performances, even in front of the caliph, who would toss coins to the actors. On one occasion, an actor searched for a rolling coin under the ruler’s festive robes. Such close contact with masked performers was deemed unsafe, and thereafter, caliphs watched new year shows from an elevated platform for security reasons. These festivities also featured alcohol, such as wine and beer, as Baghdad was at the heart of an agricultural civilization.

The Wedding Banquet, Maqama of al-Hariri, c. 1225-35/Pictures From History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

As for late December to early January, the time we now associate with the beginning of the new year, different celebrations took place in Baghdad. Among Persians and Zoroastrians, the winter solstice festival (December 21–22) known as Shab-e Yalda was particularly popular. Interestingly, this holiday most closely resembles our modern New Year.

On the eve of the celebration, people cleaned their homes and replaced carpets, household items, and much of their clothing. The central event was a family feast featuring nuts and fruits such as watermelons and pomegranates. The festivities took place at night, and staying awake was essential as it was believed that evil forces could otherwise enter the home on the longest night of the year.