Although an ancient proverb says that all roads lead to Rome, in France, they undoubtedly lead to Paris. Anyone who has travelled through France by train or car will agree with this. Such perception is also influenced by our traditional historical education, which tells the story of how primitive societies gradually progressed over centuries from savagery to centralized states. However, in other European countries the situation with capitals is more complex. Paris was chosen as the residence by the actual founder of the Frankish kingdom, Clovis, in the early 6th century, which is one and a half thousand years ago. This is a very respectable age even for the old Europe.

Either the village or the town of Paris

Let's try to discern the birth of the great city in a small fishing village founded by the Celtici

Walter Crane. The judgement of Paris. 1909 /Wikimedia Commons

The Celts, whom the Romans called Gauls, prospered. Notably, they, led by Vercingetorix, fiercely resisted Julius Caesar, the proconsul ruling the Cisalpine and Gaul of Narbonne, which still retained some independence from Rome.i

Lionel Royer. Vercingetorix throwing down his weapons at the feet of Julius Caesar. Musée Crozatier in Le Puy-en-Velay. 1899/Wikimedia Commons

Medieval chroniclers and later historians have indulged in imaginative speculations about the city name, forgetting its ethnonym. Some connected the origin of the Parisians with Paris, the son of Priam and Hecuba, seeing them as descendants of the Trojans.i

A Roman city of local importance

Romans knew how to swiftly and usually bloodlessly assimilate conquered lands, relying on local leaders and their families. This gave rise to prominent Gallo-Roman families, the societal elite, which became the stronghold of ancient civilization in Gaul for several centuries. Within a couple of centuries, the city expanded, moving from Cité to the Left Bank, and added a palace (the current Prefecture), baths (Cluny Museum), an arena (Rue Monge in the Latin Quarter), and a temple of Jupiter, where Notre-Dame now stands. Today, one can peacefully read a book on the ruins of the arena, which once held over ten thousand spectators. The remnants of the temple can be seen in the archaeological crypt of the cathedral. The cemetery was located south of the current Luxembourg Gardens, in the area of Port-Royal. In its prime, around ten thousand Lutetians, or slightly more, enjoyed all the typical amenities of ancient Roman communal services, such as central heating and water supply. In short, it was a well-established city like Nîmes, Vienne, or Lyon, but still not too large by imperial standards.

Arènes de Lutèce. Rue Monge, Paris/BNF

The classical rectangular street grid of the Roman city with the decumanus and cardo is still traceable somewhere between Rue de Sèvres, Rue Saint-Jacques, Boulevard Saint-Germain, and Rue Descartes.i

Leon Bonnat. The martyrdom of Saint Denis. 1880 /Alamy

Forces of heaven

The triumphant march of Christianity in Paris, as everywhere else, began with martyrdom. Dionysius, an Athenian, ventured to enlighten the Gauls in the 3rd century, having become the first bishop of Lutetia. For disrespectfully destroying statues of local gods, he was beheaded along with several followers on the hill of Mercury, later named the Martyrs' Hill (Montmartre). Saint Denis and Saint Genevieve became not only the heavenly patrons of Paris but also the foundational pillars of the legendary history of the French statehood.

Saint Genevieve's authority was immense throughout her long life, which directly impacted the history of Paris and the one of all France. In the second half of the 5th century, the city was conquered by the wild Salian Franks, one of the strongest Germanic tribes, which later gave its name to the country. Genevieve managed to convert their king, Clovis (481 – 512), to Christianity. He married the Catholic Clotilde, and Saint Remigius baptized him in Reims, which later became a mandatory place for the anointment of French kings. On the advice of the same saint, Clovis built the Church of Saints Peter and Paul, where he found eternal rest, side by side with Genevieve and his wife.

Paris, chosen by the long-haired Frankish kings for its favourable strategic location and remnants of past imperial grandeur, became a stronghold of Roman orthodoxy amidst the sea of barbarian paganism and Ariani

The times, in general, were dark, with people being more warrior-like than inclined to peaceful trade and the refinements of ancient education. Due to this general coarsening of manners, flourishing Gallo-Roman cities shrank to the size of small villages or, let's say... amphitheatres, gradually turning into giant dormitories. Paris was no exception and once again found the refuge on the island for several centuries. With the weakening of the Merovingians,i

Unknown artist. Saint Genevieve, patroness saint of Paris. Paris. The Carnavalet Museum. 1620 /Wikimedia Commons

It's in the bag

The strategic and usually benevolent Seine River did the Parisians a disservice in the late 9th to 10th centuries when it opened the way for invaders from the north—the non-Christian Vikings, known as the Normans or "Northmen." They plundered on all waterways, and in 845, Ragnar, without much resistance, captured the nearly defenceless Paris. Charles the Bald had to pay a ransom called "danegeld" of 7,000 pounds of silver to those marauders. With the Carolingians neglecting the defences of the western part of their empire, the Parisians had to seek help from the counts of Anjou. The Paris County dynasty originated from Robert the Strong. His son, Odo of Paris, and Bishop Goslin became famous for successfully defending Paris from the Normans in 885, an event celebrated in a poem by the monk Abbo of Saint-Germain.

Over the next hundred years, the imperial lineage gradually degenerated. In 987, the grandson of Odo, Hugh Capet,i

Coronation of Hugues Capet. Miniature from a 13th or 14th century manuscript /Wikimedia Commons

It is often said that it was exactly the time when France and its capital were born. However, for many years, the name "France" was reserved only for the present-day Île-de-France region. The need to fight against the hardened Normans was no longer necessary, and the real power of the Capetians did not extend beyond a hundred kilometres around. It was a time of feudal anarchy, often turning the life of France into complete chaos and constant disputes over land rights among major and minor lords. Their actions were somewhat restrained by the peacekeeping efforts of the Church, the gradual growth of the population, and the increasing economic importance of the cities.

In the 11th century, life outside the narrow city walls became somewhat calmer, and people started settling in the immediate vicinity under the protection of the king and major monasteries. An example of this was the town of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, whose church still stands on the eponymous boulevard, a splendid monument of mature Romanesque style.

Eugène Galien-Laloue. The Church of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris. 1941 /Wikimedia Commons

New Athens and New Babylon

The king befriended the prosperous cities and often granted them liberties in exchange for their support in dealing with his rebellious vassals. However, the largest cities in the royal domain, including Paris, were excluded from these liberties. Nevertheless, the construction of the Notre-Dame Cathedral in the middle of the 12th century and the radical transformation of the Carolingian basilica into the Abbey of Saint-Denis, both pioneers of a new architectural style, aimed to give the city and the adjacent royal monastery a unique character. Both Louis the Fat (1108–1137) and Louis VII (1137–1180) were not particularly strong personalities. The latter even allowed his wife, Eleanor, to marry Count Henry Plantagenet, the future King of England, losing not only the most remarkable woman of the 12th century but also half of south-western France. However, they were assisted by the talented chancellor Suger, the abbot of Saint-Denis. He was not only an excellent administrator and personal biographer of the kings but also a highly educated man. The Gothic style, tested in the basilica of Saint-Denis, owed much to his knowledge and sensitivity to the architectural aspirations of his time during the first half of the century.

Felix Benoist. The church of the abbey of Saint-Denis. 1861 /Wikimedia Commons

Paris was already divided into three poles: the administrative-religious Cité, the intellectual Left Bank, and the commercial-business-oriented Right Bank. During the middle of the 12th century, when Bishop Maurice de Sully demolished the early-Christian basilica to build a worthy temple for the capital, the Cathedral School also gained international authority, becoming a forge for the intellectual elite of all of Europe. During the first half of the 12th century, the University of Paris was founded, heralding a new era of education and intellectual development in the city. Peter Abelard taught there, but he was an uncompromising man and, having quarrelled with everyone, he started lecturing on dialectics and theology at the Sainte-Geneviève hill without the approval of the church authorities. This was the birth of the well-known Latin Quarter. Abelard became very popular, and schools grew in number, receiving a papal bull in 1215, marking the starting point of the history of higher education in France. In 1253, King Louis IX's chaplain, Robert de Sorbon, established a college that later gave its name to the world-famous university, which would always be associated with everything venerable, scholarly, and conservative in French science.

In the 13th century, Paris became the largest city in Europe with its 70,000 inhabitants and, for a time, its cultural capital. The prestige of the Capetian dynasty played a great role here; they pursued a successful policy of centralization and gradually absorbed almost all of the rebellious duchies and counties of France. The refined aesthetic tastes of the court towards literature, painting, architecture, and sculpture quickly spread beyond the Rhine and the English Channel, across the Alps and the Pyrenees, always bearing the imprint of Paris and the royal court. By the end of the century, there were several hundred professional craft guilds with their own statutes. Their affairs were managed by the royal provost and Hôtel-de-Ville.i

Sainte-Chapelle. Paris, France/Getty

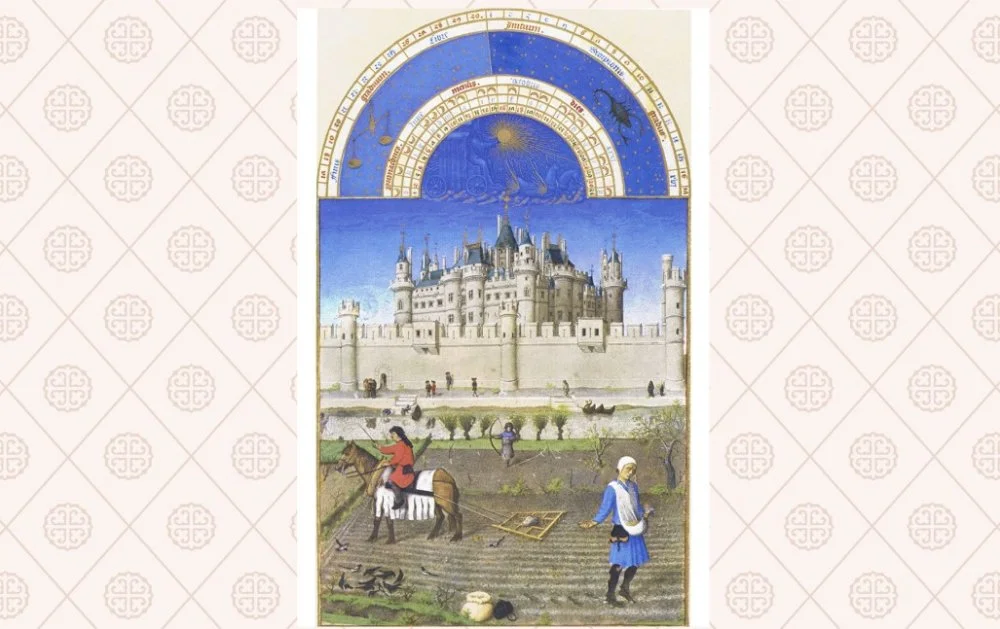

At the same time, serious construction work began outside the Île de la Cité. Philip II Augustus (1180–1223), preparing for a crusade, built the Louvre fortress on the Right Bank and surrounded the city with defensive walls. He also founded the first covered market, later known as the famous "Belly of Paris," now drastically transformed into the shopping complex Les Halles. Prior to this, traders and craftsmen had set up their stalls literally next to each other on all the bridges over the Seine. Gradually, urban amenities started to emerge, such as sidewalks and hospitals, like the 12th-century Hôtel-Dieui

The Limbourg brothers. The very rich hours of the Duke of Berry. 15th century manuscript/Photo by Pierce Archive LLC/Buyenlarge via Getty Images

The Hundred Years War (1337–1453)i

Theodor Hoffbauer. The Louvre at the time of Charles V. 1380 /iStock

In 1420–1436, Paris fell under English rule, and the city was governed by the Duke of Bedford. In 1431, Henry VI was crowned French king in the cathedral. However, the city was constantly besieged by the French forces. Successful administrative and military reforms, along with the presence of Joan of Arci

Paris took a long time to recover from the wars, and it wasn't until the 15th century that its population grew from one hundred thousand to one hundred fifty thousand. Both Charles VII and Louis XI did not like the capital and preferred the Loire Valley. Parisian architects created masterpieces of flamboyant Gothic and built impressive mansions, such as the Cluny and Hôtel de Sens, the churches of Saint-Severin and Saint-Étienne-du-Mont. The kings restricted themselves to their own residences and fortifications, but occasionally issued edicts to pave important streets.

Gabriel Rossetti. Joan of Arc. 1882 /Wikimedia Commons

The Northern Capital of Renaissance

The city flourished under Francis I (1515–1547), perhaps the most Renaissance monarch of the period.i

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres . The death of Leonardo da Vinci. 1818 / Wikimedia commons

Niccolò Machiavelli served as Florence's ambassador in Paris, and his letters show the significant influence Italians had at the French court, where people spoke their language freely. In 1546, the Louvre began to take on its modern shape under the architect Pierre Lescot. In 1533, the Italian Boccador started work on the new Hôtel de Ville, which was only completed a century later. The royal family commissioned the Fontainebleau country residence and luxurious hunting châteaux in the Loire Valley. The vibrant intellectual life, patronized by the enlightened monarch, manifested in the prestigious and somewhat rebellious Royal College, which challenged the Sorbonne. Today, it is the Collège de France, a centre of free science, the pinnacle of dreams for the most talented French scientists. Aristocratic salons, imitating the court, started gathering intellectuals and art connoisseurs.

The king's genuine love for his capital resulted in quite a growth during his reign, the population reached 280,000, making Paris the largest city in Europe once again. Charles V referred to it, paraphrasing a famous expression related to Rome: "non urbs, sed orbis," meaning "not just a city, but a whole world."

As with everywhere in Europe, the humanistic softening of manners in Paris was accompanied by an increase in religious intolerance. The capital became a stronghold for often radical Catholics, while Protestants (Huguenots) rallied mainly in the west of the country. Paris became the stage for many significant events of the religious and civil wars in the second half of the 16th century. First, the struggle broke out between the Huguenot Prince of Condé and the Catholic Duke of Guise, the two warring factions. This was followed by wars involving three Henrys: King Henry III, Henry of Guise, and Henry IV of Navarre. On the night of St. Bartholomew's Day (August 23, 1572), Catholics, fearing a Protestant conspiracy against the royal family, killed over 3,000 Huguenots.

François Dubois. The St. Bartholomew's day massacre. Paris. Year 1572 /Wikimedia Commons

Nevertheless, the city continued to grow, and neighbourhoods like the Marais and the St-Germain-des-Prés retained memories of those difficult times, such as the Hôtel Lamoignon in the fourth arrondissement, which now houses the Historical Library.

Relative peace only returned with the ascension of Henry IV (1594–1610), the founder of the Bourbon dynasty. Henry believed that "Paris is worth a mass." After capturing the capital following a long siege, he renounced Protestantism and embraced Catholicism, pursuing a religious compromise. As a pragmatic king with absolutist ambitions, he had the opportunity to create a capital worthy of the new power. He was responsible for the arrangement of the first geometrically regular square in Paris, framed by the unified architectural ensemble of the Royal Square, with the facing each other pavilions of the King and the Queen, now known as Place des Vosges. On the western tip of the Île de la Cité, the complex of Place Dauphine and the New Bridge (which is, in fact, the oldest bridge today) emerged. Besides being a genuine urban complex, albeit a small one, the New Bridge was the first open bridge without traditional medieval buildings on it. This innovation was seized by itinerant traders of all kinds of things, dentists, artists, charlatans, and booksellers. The latter group, the booksellers, retains some rights to the adjacent quays of the Seine today. However, the history of these famous and poetic quay areas began precisely around 1600.

After the death of Henry IV on the Rue de la Ferronnerie in 1610, at the hands of the Catholic fanatic Ravaillac, the reins of power passed first to his widow, Marie de Medici. She ordered the Luxembourg Palace to be built for herself. Later, Cardinal Richelieu, the minister of Louis XIII, took charge of affairs. Richelieu was an enthusiastic state builder, a staunch absolutist, and also a city planner. The Sorbonne University, where he received his doctorate, was reconstructed and took on its present appearance under his guidance. He also completed the construction of the Tuileries Palace and Jacques Lemercier received a commission to build the Cardinal's personal palace, the future Royal Palace (Palais Royal), located to the north of the Louvre.

The area between this palace and the old National Library on Rue de Richelieu (once the palace of Cardinal Mazarin) preserves the memory of those decades familiar to all through Dumas' novels. These were the years of Catholic reaction against the principles of religious tolerance of the first Bourbon, and in Paris, which became an archbishopric in 1622, the best efforts were devoted to creating such magnificent churches as the Val-de-Grâce in the Baroque style, splendidly reflecting the triumph of Catholicism.

Nicolas Jean-Baptiste Raguenet. The Joute des mariniers between the Pont Notre-Dame and the Pont-au-Change. 1751/Photo by Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

Paris lost to Versailles

King Louis XIV, the Sun King (1643–1715), was not overfond of Paris due to the anti-royal Fronde: he was just a child when a crowd of Parisians broke into the palace and forced the flighty regent Anne of Austria to show them the heir to the throne. The Parisians were tired of the omnipotence of this Spaniard and her Italian upstart, Cardinal Giulio Mazarini. The family had to flee the city. Louis did not forget anything and, upon maturing, invested insane amounts of money in creating a new suburban residence in Versailles, which became the centre of state life from 1682. His brilliant minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, was not only involved in all internal policy matters but also in the embodiment of absolutism in the Parisian cityscape, which personally did not greatly concern Louis XIV. The squares of Victory and Vendôme, the first boulevards, the triumphal arches at the entrance to the city from the suburbs of Saint-Denis and Saint-Martin, were all his initiatives glorifying the military victories of the sovereign, whom the capital saw about 80 times during his long reign and that happened only on major holidays.

At the turn of the 17th to 18th centuries, the complex of the Hôtel des Invalides emerged. This was a monument to Louis XIV's not very successful military policy and an excellent representation of Mansarti

Pierre Denis Martin. Visit of King Louis XIV to the church of the Royal Hotel des Invalides. 1706 /Wikimedia Commons

Louis XIV perished and the whole era was gone. The court returned to the uncomfortable and unfamiliar, foreign Paris for a few years under the rule of Philippe of Orleans, the regent acting on behalf of the young Louis XV. The festivities organized by the prince smoothly turned into orgies, and gaining such a high approval, became an object of imitation in all layers of Parisian society. As soon as the king reached adulthood, he returned from this "new Babylon" to Versailles. Despite this, Paris became the capital of the Enlightenment: new ideas were born in the salons of wealthy women who patronized rebellious encyclopaedists and enlightenment thinkers. Catherine II, following this trend, invited Diderot to her court and then complained that the philosopher gestured so vigorously during their conversations that she ended up all covered in bruises. Perhaps she exaggerated a little.

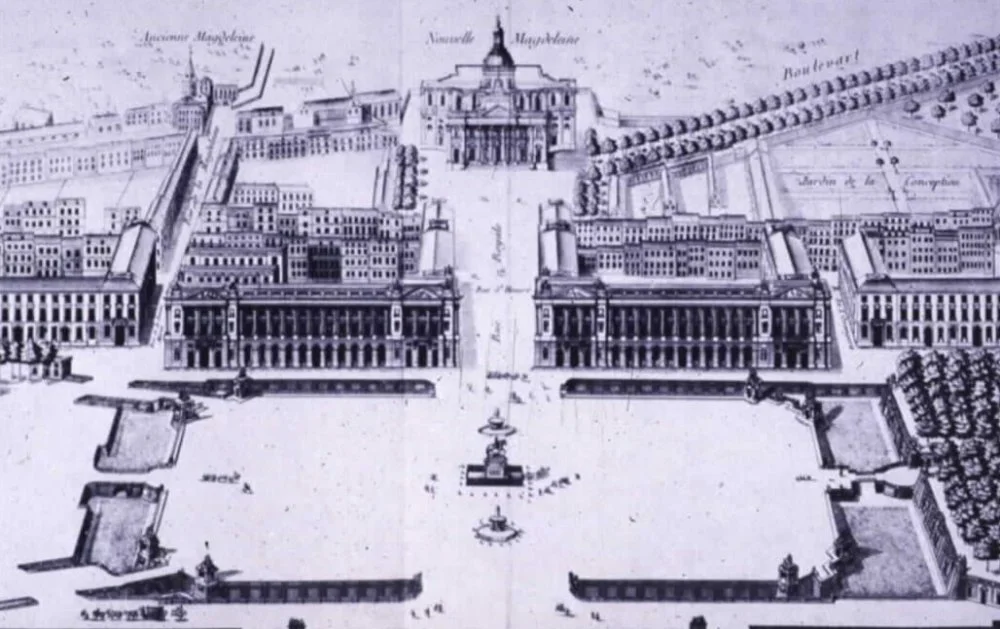

The most luxurious salons in Paris were hosted by Madame Geoffrin and Madame du Deffand. Madame Lenormand d'Étioles, born Poisson, became the official mistress of the king and also was appointed the Marquise de Pompadour by the grace of Louis XV. She governed France from 1750 to 1770. She managed to coax his majesty to sponsor several major architectural projects, including the Place Louis XV designed by the royal architect Gabriel, now known as Place de la Concorde. Unlike the squares of the 17th century, it was open to the city on all sides, seemingly absorbing all its main thoroughfares and connecting them to the palace. This ensemble can be considered the starting point of the new Paris as a world capital of the modern type. The talented architect managed to embody the idea that ruling monarchs should leave a visible mark not only in their palaces but also in their capital, not only as saviours of the homeland but also as city builders. He did it with such tact that no one would ever think of seeing in Place de la Concorde an embodiment of the absolutist ambitions of the last Bourbons. The same can be said about another grand construction of those years: the Church of Sainte-Geneviève, which became the Panthéon (1757-1790), a masterpiece of Neoclassicism, designed by Jacques-Germain Soufflot.

Ange-Jacques Gabriel. The project of the Place de la Concorde. Paris. 1758 /Alamy

The same years represent the peak in the influence of the mocking skeptics, who challenged outdated religious, scientific, and philosophical principles, and who published the "Encyclopedia" in Paris, they were Montesquieu, Diderot, Voltaire, and Rousseau. At the same time, Beaumarchais,i

Malapeau Claude-Nicolas. Transporting the writer Voltaire's ashes to the Pantheon. 1795 /BNF

Paris hits back

In 1789, even the convocation of the Estates-General, a representative institution forgotten since 1614, could not save the monarchy. Paris was shining, and France was not in dire straits, remaining the most powerful country in Europe despite all its problems. But it was in Paris that passions boiled, and aesthetic salons transformed into political clubs. Even within the ruling elite, figures like Lafayette preached for a moderate revolution similar to one of Washington. The developing press played its part among the educated bourgeoisie. The National Assembly gathered on 20 June 1789, in the tennis court at the Tuileries Palace, and the Third Estate pledged not to disband until France had a Constitution.

The capture of the impregnable but almost empty royal prison, the Bastille, on 14 July, and its physical destruction became a symbolic act, marking the beginning of a new history. All feudal privileges were abolished, and the monarchy was dissolved on 22 September 1792. Soon, the Reign of Terror began. Dr Guillotin's invention was set up on the Place Louis XV, renamed to the Place de la Révolution, and later to the Place de la Concorde. During the Great Terror in 1794, 1,300 heads were severed on the Place du Trône Renversé (now Place de la Nation). Beside the use of the guillotine, there was a flourishing of ideas: Paris feverishly read everything printed by various political motions and parties. Multiplying clubs like the Cordeliers and Jacobins decided the fate of New France and its capital. The revolutionary thinkers, heavily influenced by Rousseau and Voltaire, who largely became victims of their own movement, sought to organize everything based on the principles dictated by Reason. The Cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris was dedicated to that Reason during the revolutionary years; they removed from its facade the statues of biblical kings of Israel, having mistakenly taken them for the medieval kings of France. The Sainte-Chapelle was turned into a warehouse.

Paris, naturally, suffered greatly from the revolutionary iconoclasm and its usual companions—spontaneous vandalism and looting of treasures. Great monuments of the Middle Ages, even Notre-Dame, quickly decayed, as evidenced by drawings and engravings from the early nineteenth century.

Jean-Pierre Houel. The taking of the Bastille. 1789 /BnF

However, paradoxically, by destroying, the revolutionaries also ‘nationalized’ the treasures of the overthrown authority and aristocracy, rightfully recognizing them as works of art, historical evidence, and national heritage. Thus, based on the royal collection, the Louvre was born in 1793, becoming the first public museum in France. It was then named the Central Museum of the Arts of the Republic (the Muséum central des Arts de la République).

Charles Monnet. Execution of Marie Antoinette. Paris / Wikimedia commons

The center of the new empire

Despite all the democratic enthusiasm, the successive new statesmen were primarily administrators and centralizers. To establish a strong state power, only a grand figure was missing. Napoleon Bonaparte seemed to know how to direct the martial spirit of the masses and how to reorganize society on the principles of modern etatism. After crowning himself emperor in the presence of the captive pope at the Notre-Dame Cathedral, which was hastily returned to the Catholic Church, he gave France the Civil Code and a new system of higher education. Its foundation is engraved in the newly created Parisian grandes écoles (high schools), which continue to shape the elite of the government officials and scholars to this day. The emperor had to rule in the most beautiful city in the world, so the embankments, bridges, and the Canal Saint-Martin were embellished, and buildings like the Stock Exchange, Madeleine, and the Arc de Triomphe were constructed. Masterpieces were brought to the Louvre (which became the Imperial Museum) from everywhere, especially from Egypt and Italy. The Imperial (future National) Library was enriched with carefully selected ancient manuscripts. Napoleon's official architects, Percier and Fontaine, laid out Rue de Rivoli in honor of one of his glorious victories, while the continuation of the Champs-Élysées was named Avenue de la Grande Armée (Great Army). Everything, including the tiniest detail in the interior of the victorious leader's private apartments, had to unite Napoleonic Paris with the great imperial past inherited from Rome. Thus, the international Empire style emerged.

Antoine Montfort. Napoleon's farewell to the Imperial Guard. 1814 /Alamy

For modern left-wing Parisians, the nineteenth century is an era of heroic revolutionary history, when they learned to defend their rights with weapons in hand. This century, of course, began in 1789. Paris was repeatedly filled with barricades. In 1830, the July Monarchy replaced the Restoration epoch. The bourgeois king Louis-Philippe did not like being reminded that he came to power on the shoulders of the rebellious Parisians. One can only imagine his disgruntled face when he saw Eugène Delacroix's monumental painting Liberty Leading the People at the solemn opening of another art salon in May 1831. This painting later became one of the symbols of France. No one saw Delacroix with weapons in hand amidst the raging crowd, unlike, for instance, Daumier. However, from his windows on Quai Voltaire, he could see everything that was happening around the Hôtel de Ville during those July days. In 1848, the ashes of new barricades brought forth the Second Republic, which succeeded to carry out a series of democratic reforms but was replaced in 1851 by the Second Empire under Napoleon III. In 1871, the Paris Commune revolted against the republic of Adolphe Thiers, refused to surrender Paris to the besieging by the Prussian army, and in its last throes managed to burn the object of the dreams of all Parisian revolutionaries—the Hôtel de Ville itself and the Tuileries in the bargain. The Commune was shot down in street battles, imprisoned, exiled, and destroyed. The Père-Lachaise cemetery holds a silent memory of the massacre. Some French people have a less fond opinion of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, known as Sacré-Cœur, at the top of Montmartre, the main hill in the city. This temple, built by triumphant Catholicism in an eclectic style, was intended to atone for the sins of the Commune, particularly the murder of the Archbishop of Paris. This ambivalent monument became one of the main vertical dominants of the capital, rising above Notre-Dame and the dome of the Hôtel des Invalides.

Eugene Delacroix. Liberty leading the people. 1830 / Alamy

Towards a modern metropolis

The vibrant social life of Parisians was reflected uniquely in the city's appearance, which took shape around the main monuments of different eras in the nineteenth century. Napoleon III entrusted Baron Georges Haussmann, the prefect of the Seine department, with a radical transformation of the capital. Haussmann relied on urban development projects proposed by the Commission of Artists formed by the revolutionary Convention in 1793. By the eighteenth century, the appearance of the city of European absolutism no longer satisfied the aesthetes: ‘Paris, possessing an infinite number of marvellous buildings, presents a somewhat dissatisfactory view in its ensemble: its exterior does not correspond to the idea that the foreigners should have formed of the capital of the most beautiful kingdom in Europe; it is a jumble of crowded houses, a chaos in which chance seems to have reigned.’ This is what Abbot Laugies wrote in ‘An Essay on Architecture’.

Adolphe Yvon. Napoleon III handing over to Baron Haussmann the decree. Paris. Carnavalet Museum. 1865 /Alamy

Most of the old neighborhoods had dirty narrow streets, breeding grounds for rats, diseases, and crime, slums in the heart of the city that so deeply shocked the ‘Russian traveller’ Nikolai Karamzin, and which were so convenient for street battles against the state—all of this was destroyed between 1853 and 1869 at the will of a professional lawyer. He decided that streets should radiate from the main squares like rays of the sun; houses should resemble each other and have six to seven floors in height; their sloping roofs scorching under the July sun and freezing in the January frosts should have attics densely populated by servants. Today, those rooms, chambres de bonnes, are still being rented out. The balcony, stretching along the entire façade somewhere at the level of the fourth floor, was meant to lift up the gazes of the passers-by toward the sky. The city had to appear modern, fresh, light.

Henri Linton. Rebuilding of Paris by Baron Haussmann. 1860/

Haussmann did exactly what the capital, perpetually imperial despite the constant change of political costumes, had long awaited: a break from the disorderly Gothic, clerical, and barbaric medieval past in favor of calm orderliness, sometimes aristocratic, sometimes bourgeois, combined with cheerfulness and youthfulness. Only the islands of Île de la Cité and Île Saint-Louis, certain streets, squares, the Latin Quarter, and Le Marais survived. The intervention of romantic geniuses like Victor Hugo and Prosper Mérimée, and professional architect Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc was necessary to prove to Parisians the value of Notre-Dame, Sainte-Chapelle, and the entire medieval heritage of France. Monuments began to be restored: Notre-Dame, for example, received its roof and spire, which served faithfully until the recent devastating fire, and the former abbey church of Saint-Denis received a new facade, a somewhat free interpretation according to today's restoration laws, in the Romanesque style.

Let's not forget that the nineteenth century was the era of the industrial revolution. The beautiful capital of France had to compete in every way with its main rival, London, which had reached a population of one million by 1800. Although Paris did not create a Crystal Palace,i

Construction of the Eiffel Tower. Paris, France. 1888 /Photo by Roger Viollet/Getty Images

The twentieth century began with another Exposition Universelle, where Paris welcomed significant innovations: the first metro line that took unsuspecting passengers from Porte Maillot to Bois de Vincennes in just half an hour; a magnificent bridge named after the peace-loving Russian Emperor Alexander III, the founder of the Entente; the Grand and Petit Palais, originally intended for a one-time exhibition but still preserved for future generations. This was the start for the flourishing of Art Nouveau. The pre-war years in Paris strongly resembled other European capitals of those times, with a vibrant cultural life set against the backdrop of ‘pineapples in champagne’ and oysters à volonté (‘all you can eat’). The ‘Belle Époque’—that's how Parisians nostalgically remembered that happy time in the 1920s, after several years of the most difficult, albeit glorious, First World War (1914–1918), which is commonly referred to as the Great War in France. During the battles for Paris, troops were transported to the front lines, located 15 kilometers from the city, by taxis. The capital periodically shook from the rumble of thunder as the giant German cannon Bertha pounded the city from dozens of kilometers away without precise targeting. The nearly forgotten great novel The Thibault Family, written by the historian writer Roger Martin du Gard in the heat of the moment, beautifully captures the Parisian atmosphere during the pre-war years as well as the psychological aftermath of the war on the good Parisian bourgeoisie.

The interwar decades are called ‘crazy’ by some and ‘anxious’ by others: like other European states, France balanced between democracy and nationalist extremism, trying to drown out the horrors of the past war with a bustling city life, hoping that it was the last one. However, director Jean Renoir showed in one of his great films that such a belief was a ‘grand illusion’.

In June 1940, the Nazis entered Paris without a fight, which is why Parisians always had mixed feelings about Philippe Pétain, the marshal who surrendered the city. Thanks to this elderly hero of the First World War, the capital survived for the second time in the global meat grinder. Charles de Gaulle, an unknown disciple of Pétain, recently promoted to general, spoke on the radio with a three-minute appeal to all freedom-loving Frenchmen, but he was unheard and flew to London to organize the Resistance. Paris was covered with swastikas, replacing the national tricolor. The Gestapo took over Saussens and Lauriston streets, and Avenue Foch. Many major Parisian firms worked both for the occupants and for the Resistance, which gradually gained strength.

For the German officers, the capital of all European pleasures was certainly more attractive than, say, the Eastern Front. Hitler visited Paris only once, was disappointed, but decided not to destroy the city. He changed his mind at the very end of the war, after the Allies landed in Normandy. But it was too late: on 23 August 1944, General von Choltitz, the commander of the Paris garrison, did not obey Hitler's order to burn Paris, for which he received the grateful memory of the French. By that time, the Parisian rebels had already raised the French flag over the Hôtel de Ville, and on 25 August 1944, General Leclerc's 2nd Armoured Division entered the city through the Route d'Orléans, a street that later received his name. In the evening of the same day, General de Gaulle triumphantly marched down the Champs-Élysées to the Hôtel de Ville.

Frederick Beaumont. Tertre Square. Montmartre, Paris/Alamy

The last revolution in Paris

Georges Pompidou. The National Center for Art and Culture. Paris/Getty

De Gaulle was an indispensable figure in extreme situations, but apparently too authoritarian and old-fashioned for the rapidly developing and democratizing French society. A symbol of national unity, he became the temporary president until 1946, and then he was re-elected during the Algerian crisis in 1958. However, May 1968 marked the end of his unusual political career. The residents of the Latin Quarter and today's academic and political establishment still remember those days when students took to the streets by the thousands, pulling cobblestones from the pavement and demanding radical reforms in education. Their demands, in an expanded form, were supported by all of France, and the wave of this initially non-political revolution swept across all of Western Europe.

Haussmann’s Paris of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as an architectural-urban entity, seemed frozen in the state of this ‘young’ but already venerable oldness. You can find certain features of its face on the Champs-Élysées and any of the surrounding boulevards, the descendants of long-gone fortifications (the word ‘boulevard’, from Middle Dutch bolwerk, once meant a special type of fortification for the artillery during the early Modern Era). Two World Wars and the succession of socialist and conservative governments seemed to pass over the city without touching it, except for a decrease in cobblestone-paved streets. Parisians cherish their traditions, so if you regularly have lunch for a couple of weeks at a small café on Boulevard Raspail, you will undoubtedly become a clueless participant in some demonstration, in which the Parisians protest to defend someone's rights, and the syndicates justify their existence. Now, it's not a suicide mission but a good reason to have fun. Modern, futuristic, and fast-paced life has embedded itself in the surroundings of Paris with high-speed TGV trains and the automated Météore metro line.

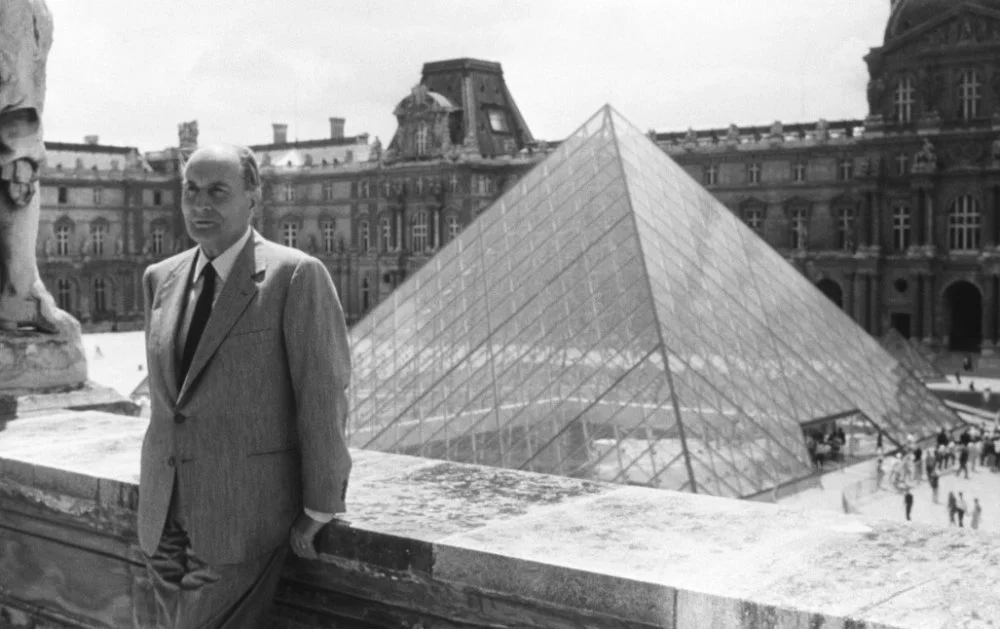

Francois Mitterrand at the Louvre. Paris, France. 1989 /Photo by William Stevens/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Starting from Georges Pompidou, many presidents consider it their duty to leave a cultural mark on the capital. Pompidou's legacy includes the monumental museum of modern art, the Beaubourg, situated between Les Halles and the Marais district. As an urban artefact, it was a slap in the face of public taste for its time. Today, its externalized communications and all those giant colorful pipes no longer surprise anyone. François Mitterrand entered the city's history with at least three architectural mega-projects. First is the Grande Arche de la Défense, the focal point of the business district and simultaneously the end of the perspective line starting from the Louvre. Around the same time, the Louvre itself received the glass pyramid—a bold combination of classicism and high-tech, created by I.M. Pei, a Chinese-American architect. The Opéra Bastille became Europe's largest theatre in terms of its area. However, the president's name is most associated with the new National Library. Its four towers are mostly uninhabited, and intellectual life is concentrated in the tall, quiet glass-and-concrete halls surrounding the sequoia-planted inner garden.

Symbolically, the library took the form of a ship, swaying on the waves of the Seine, a ship that, like Paris, fluctuat nec mergitur—‘floats and does not sink’.

Following his socialist predecessor, the Gaullist Jacques Chirac made significant efforts to create a new large-scale ethnographic museum—the Musée du Quai Branly. Jean Nouvel, arguably one of the most talented French architects of our time, won the competition for this project. This museum of world art and culture, in its turn, bears the name of the head of state. Perhaps such a form of perpetuating the memory of the leaders of a democratic state in large-scale buildings is not a bad tradition for a European capital.