When we think of the Silk Road, the first image that comes to mind is often caravans of camels laden with bolts of fabric and sacks of spices. But in reality, it was much more than a trade route—it was a sophisticated, sprawling infrastructure network complete with its own ‘passports’, postal stations, and caravanserais that functioned like hotels and logistics hubs—part hotel, part warehouse, part customs office—that kept commerce and people moving. British researcher and writer Nick Fielding tells the story of what long-distance travel looked like centuries before trains and airplanes, revealing a world that was at once highly mobile and surprisingly well connected.

From Steppe Conquerors to Empire Builders

The rise of the Mongol Empire in the thirteenth century marked a transformative period in world history, blending conquest with remarkable ingenuity in governance. This nomadic empire, and the states that followed in its wake, were able to rule most of Eurasia for almost half a millennium. Its direct successors—the Ilkhanid dynasty, Golden Horde, and Yuan dynasty—as well as derivative formations like the Mughal Empire were not just unprecedented in their size and prestige, but were also responsible for many political, social, and military innovations, allowing them, in part at least, to survive well into the nineteenth century.

The common view that the Mongols and their allies sought only to plunder and destroy has long been challenged by historians, who argue that ruling such a vast empire required equally vast administrative skill, commercial acumen, and strict political control. These, in turn, transformed what had once been simply a message system for the military elite into the vast interconnected network of trade and travel routes—including those of Iran, Russia and China—that made up what we now call the Silk Road.

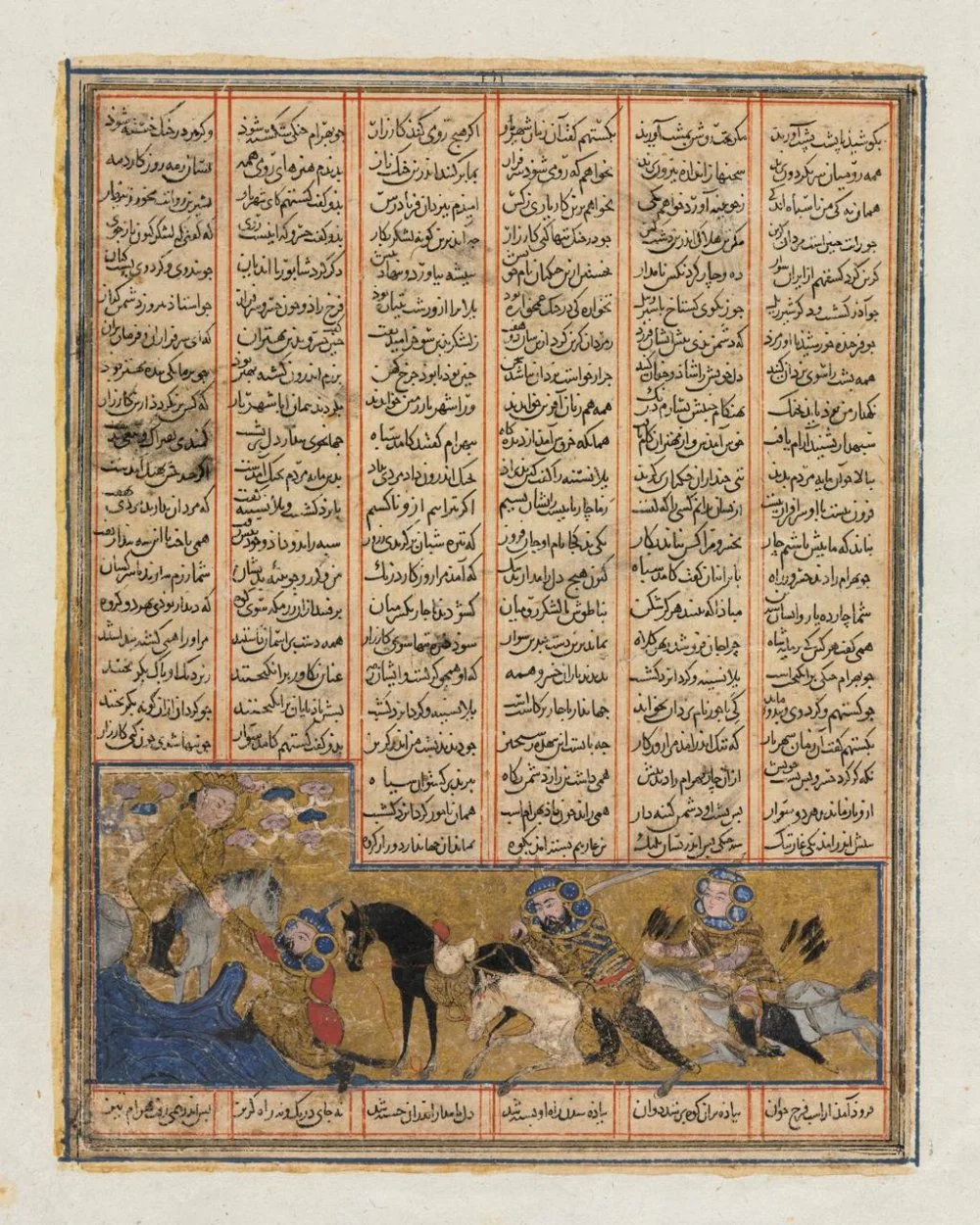

Episodes from the Reigns of Khusrau Parviz and Nushirwan from a Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Firdausi. Circa 1299 / Wikimedia Commons

Networks of trails have existed in Central Asia for millennia. Indeed, the huge size of Asia and its comparatively dispersed and isolated populations meant that traveling was always a perilous occupation. But it was the Mongol Empire, in particular, that transformed travel, offering speed and safety across the continent.

The Yam: The Arteries of Empire

The best-known expression of the formidable administrative abilities of the Mongols was the yam posthouse system, with its use of gerege ‘passports’, which bestowed upon its bearer, who was typically an official or envoy, the right to travel, demand provisions, and command respect. In its way, it developed the first globalization movement in world history, facilitating the swift transfer of ideas, information, and goods across vast distances. From these exchanges, Chinese scholars became acquainted with the astronomy of the Islamic world and the mathematics of India, whilst Europeans learned about Chinese gunpowder, paper, and the compass via the Arabs.

Established by Chinggis Khan in the early thirteenth century, according to Adam J. Silverstein, the yam system was a response to the challenges posed by the rapid expansion of the Mongol Empirei

The yam system required a substantial and carefully maintained infrastructure. In fact, in some cases, they relocated whole tribes to improve its efficiency. Silverstein notes that the Bekrin tribe, who were natives of Eastern Turkestan (now Xinjiang, China) and expert mountaineers, were sent by Hulegu Khan to run the system in parts of the Caucasus.

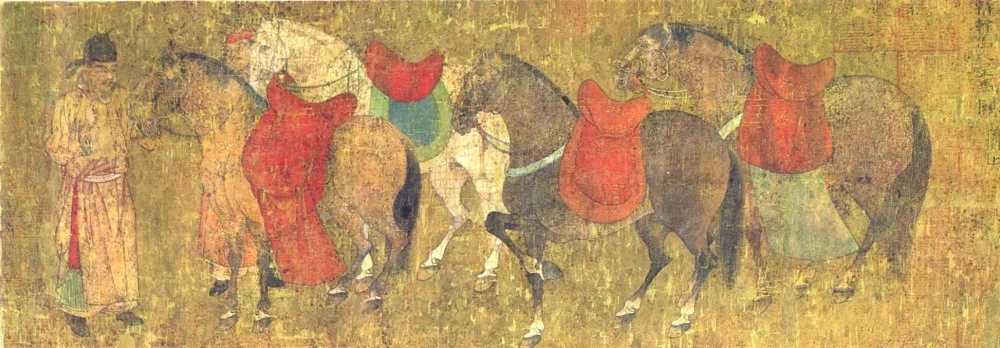

Mongol yam (probably) rider wearing. 14th century / Wikimedia Commons

Even the horses used by messengers were categorized according to their specific function. Thus, there were ‘riding horses’, short-, middle-, and long-distance horses, as well as donkeys for lighter travel. Oxen and camels, valued for their endurance, were also used extensively. Historian Marie Favereau notes that there were three strands to the yam network: the tergen yam, comprising carts pulled by oxen, camels and strong horses, but limited in range; the morin yam, which covered the regular postal route and used single riders on horseback; and the narin yam, a secret communication system for the most important messages using riders who traveled non-stop over vast distancesi

The word yam is of Turkic origin, and the Russian term yamshchik, meaning ‘postal driver', is derived from the same root via Mongoliani

Even the use of the word gerege has a long history. Apollonius of Tyana, writing in the first century CE, tells us that on his travels from Ecbatana to India, his camel bore a golden tablet on its forehead as a sign that the traveler was a friend of the king and traveled with full authorizationi

The yam (also known by its Mongolian name örtöö) posthouses meant important messages could be carried several hundred kilometres in twenty-four hours, although goods would move more slowly. By the end of Kublai Khan’s reign, there were more than 1,400 such posthouses in China alone, which, in turn, had at their disposal about 50,000 horses, 1,400 oxen, 6,700 mules, 400 carts, 6,000 boats, over 200 dogs, and 1,150 sheep. Marco Polo devotes a chapter of his book The Travels of Ser Marco Polo to explaining how the system worked. He notes:

At each of those stations used by the messengers, there is a large and handsome building for them to put up at, in which they find all the rooms furnished with fine beds and all other necessary articles in rich silk, where they are provided with everything they can want. Even if a king were to arrive at one of these, he would find himself well lodgedi

He adds that some posthouses maintained as many as 400 horses ready for use, and that across the Mongol Empire, more than 300,000 horses were kept prepared at around 10,000 posthouses. The riders themselves prepared for their grueling journeys by binding their stomachs, chests, and heads with tight bandages. They wore thick leather belts covered with bells, so they could be heard approaching the posthouses.

And in China at least, smaller, fortified posts were established every five kilometers between the main posthouses, where foot runners were stationed to ensure messages moved without delay. These runners also wore a wide leather belt on which bells were sewn so that they could be heard from a distance, thus allowing the next runner in the relay to be ready to set off as soon as his predecessor arrived. Most of the runners were infantrymen, part of the imperial bodyguard. In addition to running between posts, they would also be responsible for keeping the buildings in good condition and providing sufficient water and provisions for travelers.

The system was so efficient that news that would normally take ten days to arrive could be obtained within twenty-four hours. Even fresh fruit for the Great Khan’s table arrived in this way. A clerk at each posthouse recorded the time of each courier’s arrival and departure, whilst inspectors arrived once a month to check that no-one had been slack in their work.

Han Kan. Horses and Keepers. Circa 750 AD (Tang Dynasty)/ Wikimedia Commons

Most of the costs for the service were borne locally. Marco Polo notes that the settlements near post stations were required to provide as many horses as they could, while the expense was borne by the emperor only in uninhabited areasi

Caravanserais originated in Iran, where they were first known as chapar khaneh (post stations), and the word ‘caravan’ itself is of Persian origin. They have existed since the Achaemenid era, when Herodotus noted 111 such establishments along the 2,500-kilometre Royal Road stretching from Sardis to Susa. Most caravanserais were financed by private subscription, and while they initially provided rest and victuals for merchant caravans, in the Islamic era they became especially important in servicing the large numbers of pilgrims traveling to the holy sites in Iraq and Arabia.

Obviously, the Mongols did not invent the idea of a horse-based communication system. The Romans introduced the cursus publicus system of messengers, and in the medieval period, the papacy developed a courier network to link its bishops and cathedrals. Since at least the seventh century, the Turks, Kitans, Uighurs, and other Central Asian rulers had used couriers to connect the widely dispersed parts of their empires. However, all of these systems were inferior to those developed in the Mongol empire, both in terms of speed and spread. The Mongols merged these pre-existing systems, expanded them to fit their own ambitions, and combined them with the efficient bureaucracy.

Bernard Gagnon. Izadkhvast Caravanserai, Iran. 2016 / Wikimedia Commons

Marton Ver notes that Yuan dianzhang, an important collection of administrative edicts compiled in the late thirteenth century in China, alone contains more than 100 documents on the courier system then in usei

Evidence that similar systems were adopted elsewhere in the Mongol Empire appears in the writings of Ata-Malik Juvaini and Rashid al-Din, who describe their use in Ilkhanid Iran. The Mamluks in Egypt developed a comparable network known as the barid system. By the sixteenth century, a similar model had also spread to Russia, while the Ottoman ulak system, as well as the communication services of the Timurids and the Delhi Sultanate, and the Manchu ula system all drew inspiration from the yam. Eventually, such postal networks extended from the Korean Peninsula in the east to the Volga region in the west, and from the Siberian forest zone in the north to the territories of present-day Afghanistan in the south.

Gerege: Passports of Power

The main innovation that enabled the yam system to work so efficiently was the introduction of the gerege, a kind of official passport in the form of an inscribed metal bar. Far more than a simple travel document, the gerege was a versatile instrument that helped weave together the vast and disparate lands under Mongol control, facilitating communication, trade, and diplomacy across Asia and into Europe.

The word gerege derives from Mongolian, often translated as ‘tablet’ or ‘paiza’. It entitled its bearer to requisition fresh horses and provisions from the yam posthouses that stretched from one end of the empire to the other. Chinggis Khan understood that the rapid expansion of his domain required not just military prowess, but an effective method of administration to connect the far-flung corners of his realm and to facilitate trade.

A typical gerege, fashioned out of gold, silver, or bronze, bore an inscription, usually written in Mongolian, that invoked the authority of the Great Khan himself, instructing all who encountered the document to aid its holder on pain of death.

The design and material of the gerege reflected the rank and purpose of the bearer. High-ranking envoys might carry a gold gerege, conferring greater privileges and respect than the more common silver or bronze variants. These tablets were sometimes adorned with official seals or symbols, signifying their authenticity and the seriousness of the bearer’s mission. The gerege, thus, served as both a practical permit and a symbol of imperial favour, projecting the might and magnanimity of the khan. Armed with a gerege, messengers, diplomats, merchants, and even spies could move with remarkable speed and security from one corner of the empire to another.

There are good historical accounts of the effectiveness of the gerege tablets. John de Plano Carpini, who traveled as a papal emissary and set out from Lyon, France, in 1246 to deliver a message to the Mongol khan, was issued a gerege when traveling from the Volga region to the Mongol capital in Karakorum:

The emperor sends whomever he wishes as a messenger, and he sends as many of them as he wishes wherever he wishes. One must give these messengers the horses and expenses they commandeer without delay. No matter why they come, whether as tribute bearers or messengers, one must likewise give them horses, carts and money . . . Everyone—whether they are the emperor’s men or someone else’s—must give horses, expenses and men to a general’s messengers, as well as men to take care of the horses and serve these messengersi

Another papal envoy, Friar William of Rubruck, who traveled to Karakorum in 1253–54, described a gerege he saw thus:

It is a gold tablet the breadth of a palm and half a cubit long, on which his commission is engraved: anyone who carries it may issue what order he likes, and it is carried out instantlyi

Marco Polo, who spent seventeen years in the service of Kublai Khan, from 1271 to 1295, noted that gereges varied in the powers they conferred based on the social standing of the bearer. Imperial messengers had the highest status, followed by military commanders, governors, and lesser officials. Marco Polo records that the gereges he saw were inscribed with the words

‘By the power of eternal heaven, this is an order of the Great Khan. Whoever does not show respect to the bearer will be guilty of an offence.i

Some of the earliest bear the image of a tiger, whilst others were known as ‘falcon tablets’.

Caravanserais: Safe Havens on the Silk Road

With the collapse of the Mongol Empire in the late fourteenth century, the official posthouse system started declining. However, as trade and travel along the Silk Road expanded, caravanserais assumed greater importance, especially during the rise of the Safavid Empire (1501–1736). These were primarily business enterprises, although some were built and retained for official use.

The caravanserais, usually a square building around a central yard with many rectangular rooms in which merchants could store their goods, became such an important part of life that they found their way into literature, where the caravan itself became a metaphor for life in many poems, such as those by Saadi and Omar Khayyam.

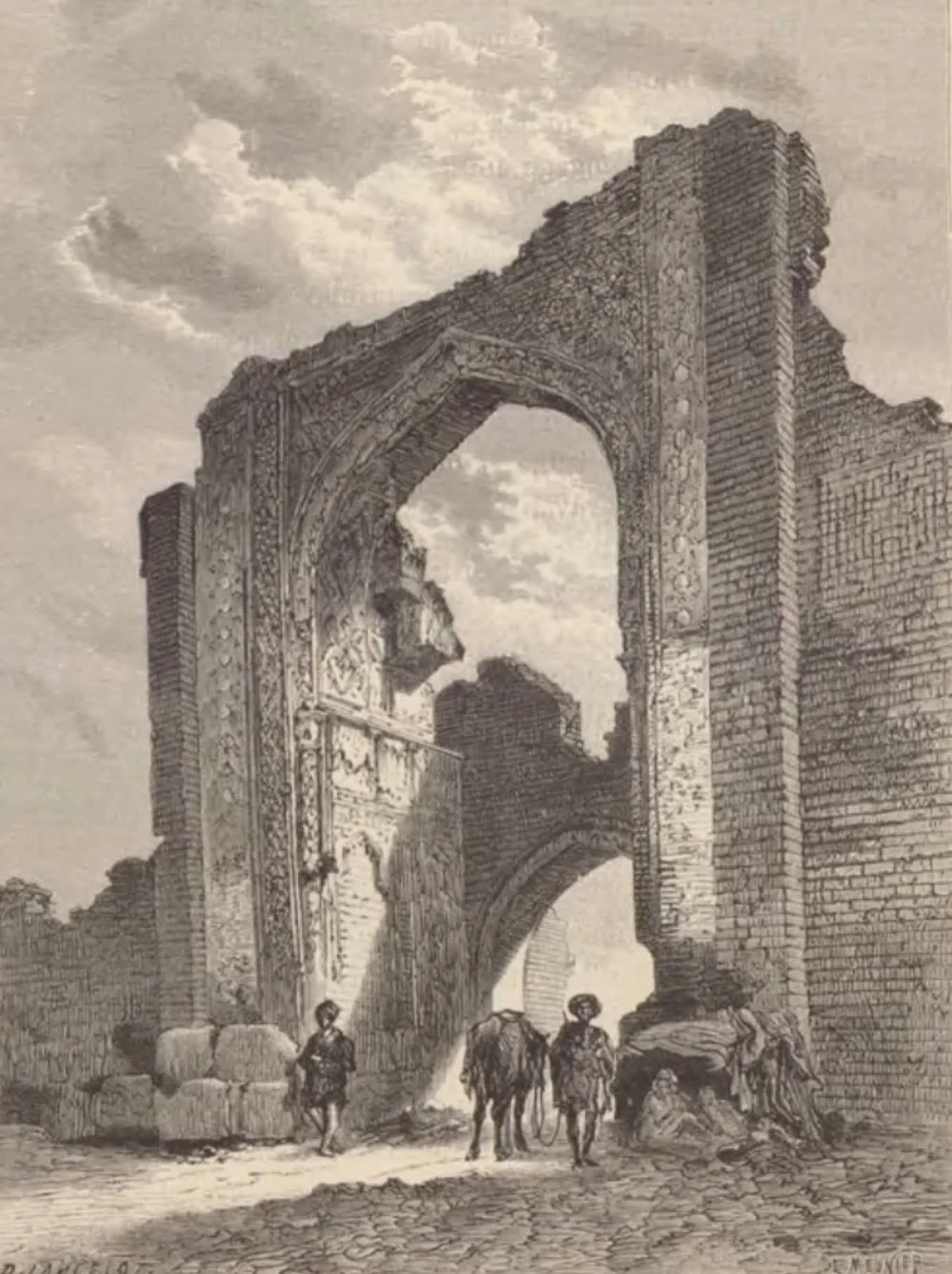

Photo: Jane Dieulafoy, engraving: Etienne Antoine Eugène Ronjat. Book "Persia, Chaldea and Susiana". 1887 / Gallica

A distinct culture grew up around the caravanserai, along with a wide and varied group of artisans who serviced those passing through, including the caravanserai dar (keeper), who would provide food such as milk, eggs, meat, and bread. Often, shops selling local produce would be part of the building. Such caravanserais, along with the Russian system of posthouses, which came into its own during the freezing winters when sledges replaced the horse-drawn tarantass (springless carriages), continued to function until the beginning of the twentieth century when cars and railways replaced them.

In summary, it was the rapid expansion of the Mongol Empire under Chinggis Khan that necessitated the equally rapid development of an efficient communication and transportation system—and later, a network of defended, safe havens in the form of caravanserais—that could accommodate large groups of traveling merchants and pilgrims. The Mongols, being a mobile, horse-centred society, knew very well how to spread information within the horde, but once they left their home territories on the steppe, they needed a robust system that allowed important information and prized goods to reach the centre from the periphery and vice versa.

Living Traces: How Imperial Networks Outlived Their Age

The yam system provided most of the answers to the need for this communication system, particularly when the practicalities of handling horses and riders was combined with the bureaucratic reforms that came from Chinggis Khan’s Uyghur and Kitan advisers. Orders, intelligence, and correspondence could be transmitted over vast distances, thus ensuring the unity of command.

The yam system also made it safer and easier to move goods, fostering commerce along the Silk Road and throughout the empire under the protection of the Pax Mongolica. It was also an essential tool in foreign relations, allowing envoys to cross borders and negotiate with distant courts, always with the threat of rapid retaliation if orders were not strictly obeyed.

The rapid growth of the system, however, created problems in some areas for the local populations—mostly nomads—who usually had to service the traffic at their own cost. As the use of the gerege grew in popularity, the number of people bearing them increased to such an extent that they were a burden on those who serviced them. Reforms by both Ögedei and Möngke improved matters by strictly limiting its use to only the most important messengers and by banning the merchant associations from using it altogether.

Audience with Möngke. Tarikh-i Jahangushay-i Juvaini. Shîrâz, 1438 / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Although later, as trade along the Silk Road increased, merchants once again became important customers for the posthouses. They survived the fragmentation of the Mongol Empire because even local trade networks could be substantial, and merchants in particular needed safe places to store their goods.

Perhaps the most extraordinary aspect of the Mongol communication network is its legacy. Most of the major modern roads in Central Asia follow routes that were once part of the Silk Road and the yam network. All along them one can still find, in various states of disrepair, the remains of caravanserais and posthouses that were first constructed hundreds, sometimes thousands, of years ago. In one form or another this network of horse and camel trails existed almost unchanged until the early twentieth century.

This is the account of the British traveler and cleric Henry Lansdell, writing in 1885 about his experience of the tsarist system of posthouses in a journey from Omsk to Semipalatinsk (Semei):

We now had before us a drive of nearly 500 miles to Semipalatinsk in the course of which we expected to change horses 31 times at a like number of stations . . . When we reached Semipalatinsk our four days’ drive of 482 miles, including refreshments, the hire of 134 horses, and gratuities to each of 44 drivers, had cost us less than £6i

The communication and transport system of the Mongol Empire and its successor states, including the Kazakh Khanate, was more than a regional logistical achievement—it was the circulatory system that connected continents. By merging nomadic mobility with bureaucratic innovation, these polities left a legacy that outlasted their political dominance.

Even today, the remains of posthouses, caravanserais, and the routes they traced remind us how the rhythms of empire once shaped the arteries of Eurasian travel and trade.