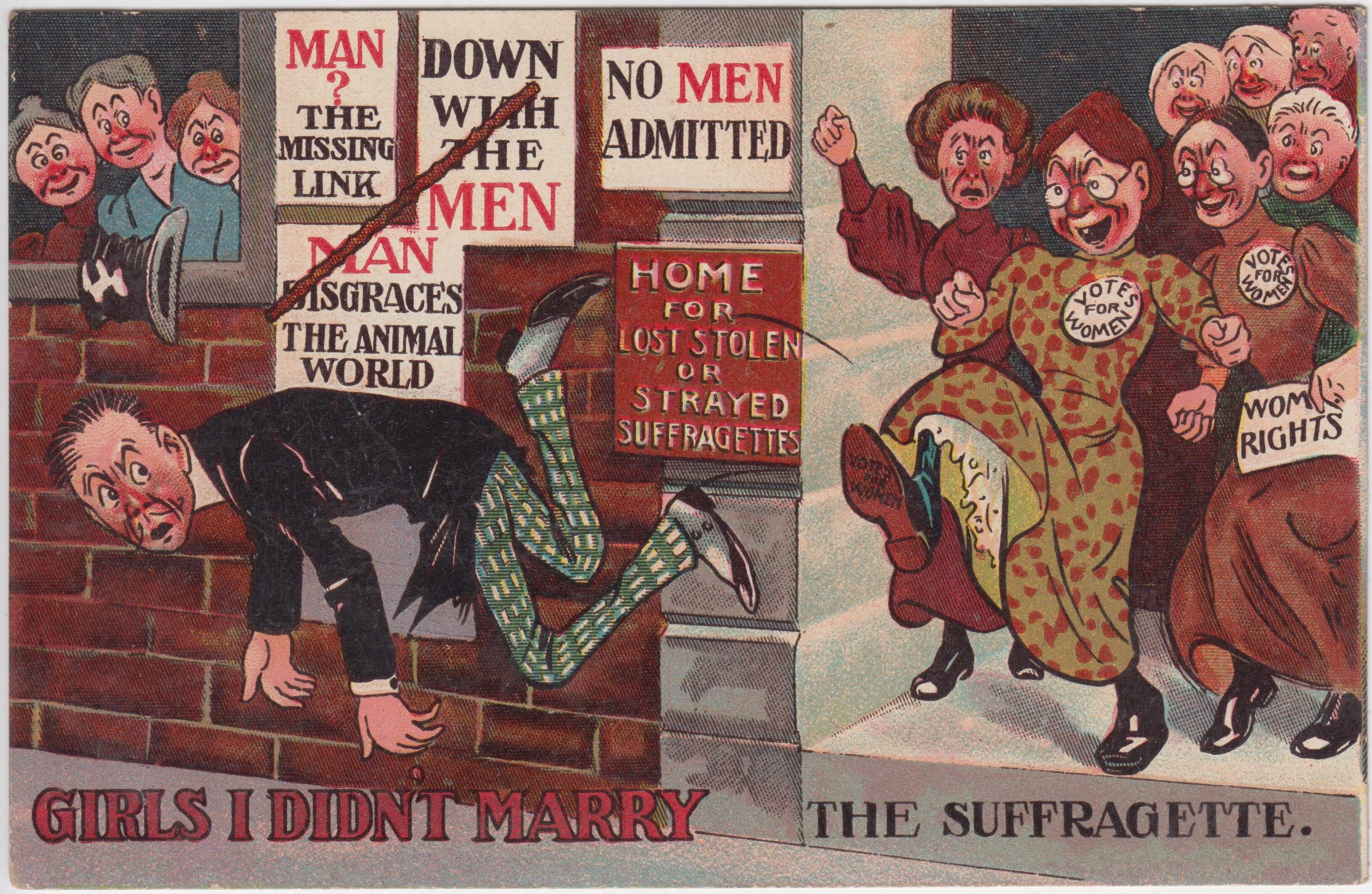

Girls I didn't marry. The Suffragette. 1900/Alamy

Angela Saini, a distinguished British researcher and science journalist, has penned her fourth book, seamlessly continuing her exploration of anti-patriarchal themes. Patriarchs: The Origins of Inequality is a natural extension of her previous non-fiction works on racial science and the enduring biases that have marginalized women throughout history.

Recently, Elon Musk mocked the film Barbie for its frequent use of the word ‘patriarchy’. Although Saini's book was released several months before Barbie, its cover, adorned with pink lettering, seems to align it with the same conversation.

However, unlike the film, Saini's book does not dwell excessively on a word. Instead, she examines exceptions to the entrenched concept of patriarchy rather than merely presenting evidence of male dominance, and her perspective combines romanticism with pragmatism. She acknowledges that patriarchy is resilient and seemingly eternal, capable of adapting through various forms and scientific justifications over time. Consequently, she argues against confronting it directly by denying its existence as a macrostructure.

In this book, for instance, Saini valiantly but fruitlessly attempts to dissuade the late Stephen Goldberg, the author of The Inevitability of Patriarchy (1973) and a proponent of the natural determinism of male dominance, from his stance. But even after forty years, Goldberg has remained steadfast in his views. In contrast, Saini proposes seeking new openings and fault lines within the impervious male discourse as a gradual means to dismantle the entire apparatus.

Throughout the book, she identifies numerous such ways, which are supported by a broad range of arguments from archeology, anthropology, and biology. Indeed, there are observable instances of subjugation in the natural world. Still, there are also far more egalitarian societies, exemplified by the bonobos, that challenge the prevailing notion of male dominance found in chimpanzee communities.

Indeed, there exists considerable and somewhat majestic inertia from the past, characterized by firmly entrenched paradigms. However, Saini questions why we should regard these historical patterns as the norm simply because they've endured for such a long time. If the very concept of taming nature (and, by extension, viewing women as more closely aligned with nature than men) originates from the Enlightenment, and if Jean-Jacques Rousseau idealized only the wives of ancient Greece who dedicated themselves to domestic life, why should we accept these peculiar notions as the standard?

In ancient Mesopotamia, women drank beer alongside men. In ancient Egypt, women could establish their own businesses. Moreover, Plato also agreed that women and men should have equal rights in education and training, and the spectacle of an aging female body in the gym should not disturb anyone. So why did everything ultimately favor men, and where is the turning point where everything can be rewritten? In this book, Saini aims to demonstrate that patriarchy is largely irrational and rooted in superstitions, much like how residents of one region in northeast Thailand have a longstanding tradition of warding off evil spirits with a large wooden phallus.

In its fervor and grandeur, Patriarchs bears some resemblance to the brilliant philosopher and anthropologist David Graeber’s final book,1

One such crossroads in Saini’s book is the ancient Turkish city of Çatalhöyük in south Anatolia, the largest surviving Neolithic settlement in the world, and its association with the theory of Old Europe, developed in the second half of the twentieth century by Lithuanian archeologist Marija Gimbutas.

According to Gimbutas, Old Europe was a long extinct, predominantly peaceful agrarian society that revered goddesses (hence the abundance of voluptuous figurines found in Çatalhöyük). It can't be directly called matriarchal, but it at least maintained gender equality. Around 4000 BCE, this utopia was invaded by Indo-European warriors who imposed an aggressive male hierarchy on the city. According to Gimbutas's Kurgan hypothesis, these tribes also originated from what is now modern-day Russia, which, in 2023, exerts a particularly hypnotic power. It's worth noting that Angela Saini's book is entirely non-speculative and devoid of sensationalism. Even Vladimir Putin is mentioned only once and in one anti-feminist pairing with his political adversary, Andrzej Duda.

The more various feminist activists championed Gimbutas's theory, the more it was scrutinized in academic circles. Critics pointed out, among other things, that the echoes of ancient goddesses seemed to appear everywhere in the Lithuanian archeologist's perception—in streams, birds, the letter V, snakes, rams, the number 3, deer, nets, zigzag shapes, eyes, and breasts. However, Saini overtly sympathizes with this theory and is firmly convinced that the gender balance was disrupted between the Neolithic and Bronze Age, leaving ancient Greece and Rome deeply afflicted with patriarchal complexes.

The chapter on the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) exposes a certain weakness in Saini's approach. On the one hand, she acknowledges the significant progress made by the Soviet Union and the countries of the former Eastern Bloc in terms of women's emancipation. On the other, she struggles to reconcile this with the dark legacy of the gulags and figures like Valentina Tereshkova. As a result, her arguments often devolve into a somewhat comical collection of gender-related grievances. For instance, she points out that even during the perestroika era, the Politburo was dominated by men (undeniably a major issue for the Soviet Politburo itself). While the percentage of female doctors in the USSR increased from 10 per cent in 1913 to 79 per cent in 1959, male surgeons still outnumbered their female counterparts and earned more. However, in 1959, all of the pharmacists in the USSR were women.

Citing unspecified, dissident samizdat sources, Saini argues that misogyny in the USSR persisted, and women, despite being granted equal rights, yearned for the past. They longed to transition from their roles as pharmacists back to being traditional wives and homemakers, echoing the sentiments of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and President Jefferson, who believed that the domestic hearth was women's main conquest and freedom.

Overall, issues of misogyny, the changing role of women, and the reactionary cult of the weak man (as exemplified by the common refrain in Vladimir Vysotsky's song ‘What Do I Need Her For?’) are fascinating phenomena of late Soviet society, vividly reflected in its culture. This subject is arguably more intriguing than the analysis of Saini's book, Planet of the Apes, which is also discussed in the book.

As a matter of interest, the expression ‘male chauvinist pig’ was likely introduced into Russian literature by Vasily Aksyonov, as evidenced in the early satirical pages of his novel The Island of Crimea (1979). But instead of delving into high art, Saini’s book retells anecdotes from Croatian writer Slavenka Drakulić about people eating bananas with their peels because many in the Soviet bloc didn't know how to handle the fruit. Saini takes these stories at face value, but a more astute researcher might have seen the banana not only as a symbol of food scarcity but also as an overt phallic symbol, akin to the large wooden phalluses used in northeast Thailand to ward off evil spirits.

What's far more interesting is Saini's exploration of the Islamic Revolution in Iran. Indeed, the prevalent portrayal of pre-revolutionary Iran that exists in the media is of a country where girls almost universally wore miniskirts, openly dined with lovers in restaurants while enjoying excellent local Shiraz wine, and had the right to abortion. Then came Khomeini, and the nation seemingly regressed into medievalism.

In reality, as the researcher argues, Khomeinii

The conclusions drawn from Angela Saini's book cannot be described as either stunning or comforting. Patriarchy is not a single, monolithic phenomenon. Instead, there are numerous patriarchal structures, each infiltrating the fabric of a particular society to parasitize it according to the existing culture of inequality. Religions, traditions, the manipulative capitalist system—all of them, with few exceptions, perpetuate the dominance of the male patriarch. Since Engels, who likened women to a form of male property, very little has changed fundamentally. Patriarchy, as a form of control, constantly reinvents itself and operates on the principle of divide and conquer.

The common Soviet saying about the Kalashnikov rifle being the pinnacle of invention (no matter where you look, it’s always a Kalashnikov) is not mentioned in this book, although it does touch upon various aspects of gender equality in different military formations. Nevertheless, Saini's thoughts inadvertently hark back to this practice: to dismantle the patriarchal ‘automatic’ as a whole, one must first learn how to assemble and disassemble it in search of its inherent flaws. These imperfections are ingrained within it, and sooner or later, they will become evident to everyone.

"The patriarchs: The origins of inequality". Angela Saini / from open access