Central Asia, the cradle of ancient traditions and a crossroads of diverse ideologies, cultures, and beliefs, has long captivated the imagination of travelers from both near and far. Through their detailed notes and vivid reflections, they have, for centuries, offered a unique, albeit not always impartial, glimpse into the rich mosaic of life in this region: bustling bazaars, nomadic customs, and enduring cultural heritage. In this series of articles, Qalam presents excerpts from their accounts and memories, spanning different eras and revealing the many facets of Central Asia.

Today, we share excerpts from the renowned Russian archeologist and historian Nikolai Veselovsky’s editorial notes on the Kazakhs, their language, and their customs.

The Russian archeologist and historian of Central Asia Nikolai Veselovsky (1848–1918) carried out extensive excavations in Samarqand and, in 1885, was dispatched to the Turkestan Region to conduct archeological research and digs. Some of his findings remain preserved in the Hermitage and other Russian museums even to this day. However, Veselovsky’s interests were not confined to archeology—he also collected local manuscripts, some of which he later published. One such work, A Kirghiz Account of Russian Conquests in the Turkestan Region, was published in St. Petersburg in 1894. It recounts the story of Kazakh Mambet’s role in defending Tashkent against Russian invaders, as narrated by his son Khalibay Mambetuly.

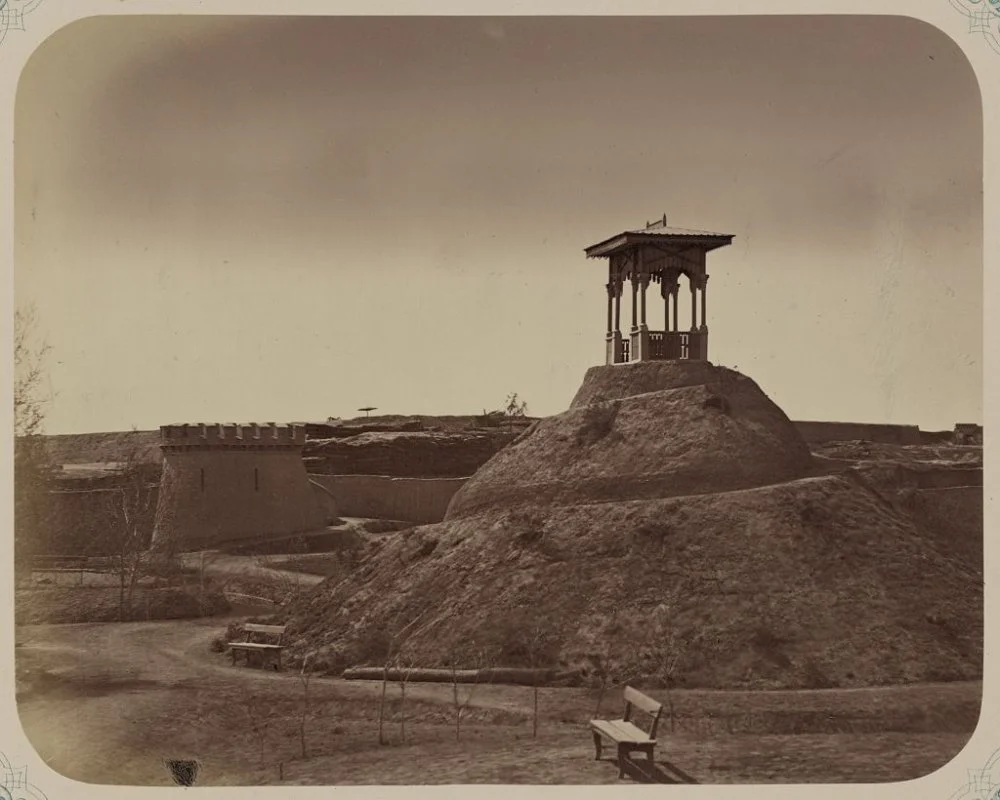

N. B. Bogayevsky. Oblast Syr Darya. City of Tashkent. Madrasa of Kokal Tash built by Barak Khan. Between 1865 and 1872/Library of Congress

In the preface to the book, Veselovsky explained that he sought to answer these questions: What did the Turkestanis think during their recent struggle with us—about themselves and about us? What did they hope for, and what did they fear from the incoming conquerors? He argued that to fully understand the situation, ‘it is necessary to hear the perspective of the other side—in this case, the defeated—otherwise, one risks falling into bias.’

N. B. Bogayevsky. Syr Darya oblast. Tashkent. Views from the garden located at the home of the regional chief official. Between 1865 and 1872/Library of Congress

In addition to Khalibay’s main narrative, the book features numerous notes by Veselovsky, some of which provide detailed descriptions of the traditions and culture of the Kazakhs in the Turkestan Krai at the end of the nineteenth century.

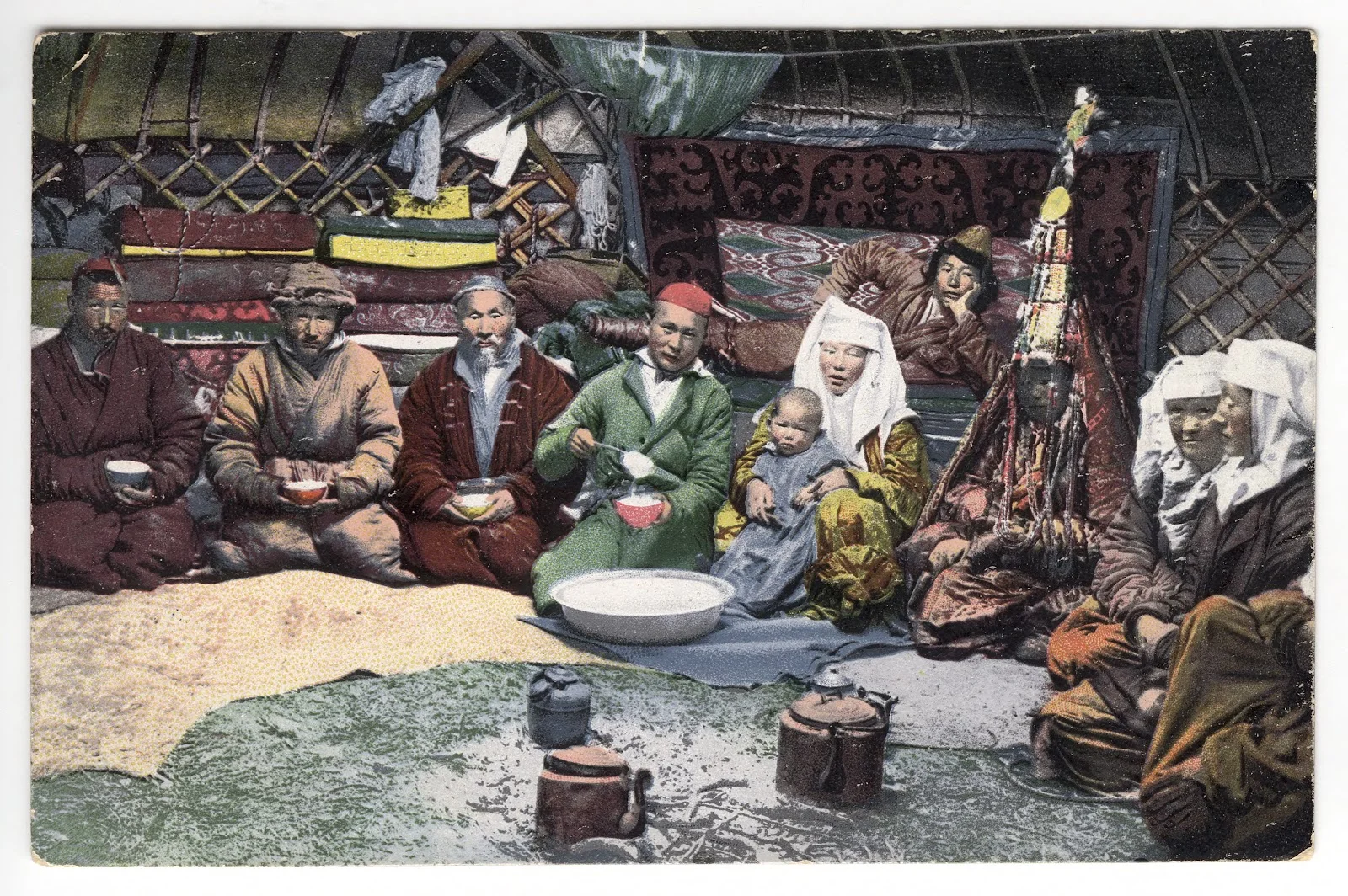

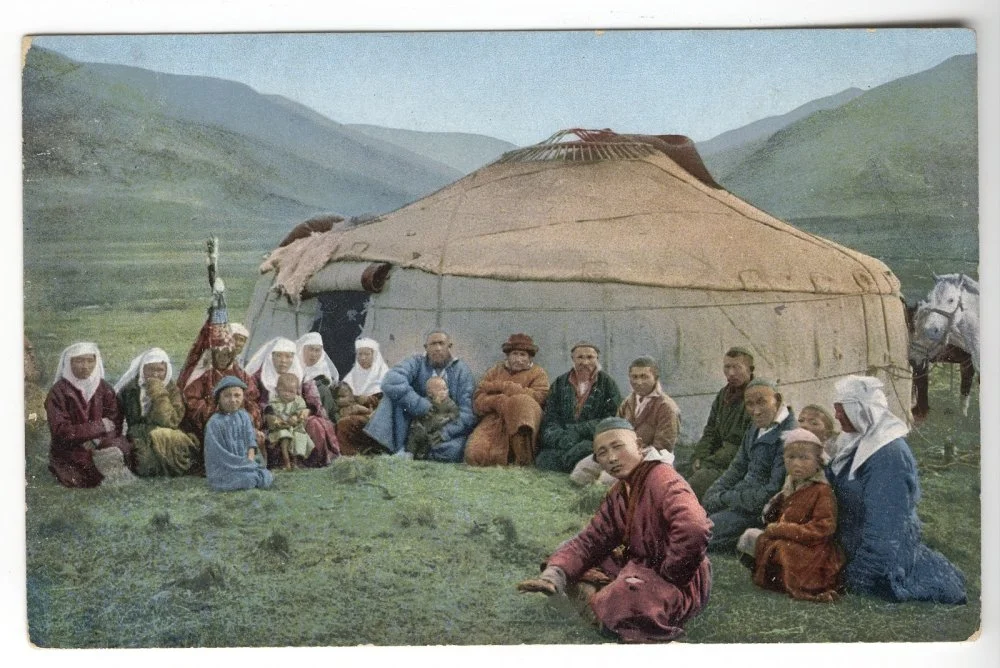

S. I. Borisov. Group of Kazakhs by a Yurt. 1911-1913/Library of Congress

He also addresses the topic of mixed marriages in the region:

In Central Asia, mixed marriages are common. A son born to a Kirghiz [Kazakh] father and a Sart, Tatar, or Kalmyk mother is called chala-Kazak [چاللا قزاق]; conversely, a son born to a Sart father and a Kirghiz or Tatar mother is referred to as chala-Sart [چاللا سارت]. A child of a ‘wild mountain Kirghiz’ [Kyrgyz] father and a Sart, Tatar, or Kalmyk mother is known as chala-Kyrgyz [چاللا قیرغیز], while the son of a Kalmyk father and a Kirghiz, Sart, or ‘wild mountain Kirghiz’ mother is called chala-Kalmak [چاللا قالماق]. Children of such unions speak both their father’s and mother’s languages equally well.

He also describes the influence of regional languages on one another, particularly on the written Kazakh language of Khalibay:

Khalibay’s language is not purely Kazakh but is significantly altered by urban or familial influences. At times he writes in Kazakh, at times in Sart, with the latter forms appearing more frequently than the former …

Veselovsky also reflects on the characteristics of Kazakh poetry:

Kazakh verses typically adhere strictly to rhythmic patterns, as they are always accompanied by a stringed instrument that maintains a precise beat. Any inconsistency between the verse and this rhythm prompts corrections to the text, either through the addition or omission of words. This adjustment is technically referred to by the Kazakhs as ‘inserting a foot’.

Veselovsky also highlights the most popular topic of Kazakh lyric poetry of that time:

The Kirghiz-Kazaks hold their batyrs (heroes) in high regard, celebrating their feats in verse and believing that any endeavor can only succeed under their leadership. Without these heroes, every undertaking is doomed to fail.

Kazakh musician with a dombra, seated. Between 1870 and 1886/Library of Congress