Since 2018, Kazakhstan has celebrated National Dombyra Day on the first Sunday of July each year, a celebration of the country’s beloved two-stringed instrument. The true emotional and cultural potential of the dombyra gained international audiences through the works of Qurmangazy Sagyrbayuly, a legendary composer the Kazakhs call the ‘father of küi’—the traditional instrumental compositions of the steppe. In fact, in 1973, his küi Saryarka was recognized as a classical masterpiece at a session of the UNESCO International Music Tribune.

In this special feature for Qalam, renowned küishii

The Life and Legacy of the Great Küishi Qurmangazy

Qurmangazy’s (1823–1896) life and musical legacy have long been the subject of extensive scholarly research, with academic interest in Qurmangazy’s life and work beginning as early as the nineteenth century and expanding significantly during the twentieth century. Each of these periods brought its own perspectives and evaluation criteria, resulting in varying interpretations of the great master's legacy. In the Russian Empire, Qurmangazy was celebrated as one of the leading dombyra players of the Bukey Horde. In the Soviet era, however, he was recognized as a national composer of the Kazakh people.

Kurmangazy monument. Kurmangazy conservatory, Almaty / Qalam

A key figure in this transformation was academician Akhmet Zhubanov, who played a pivotal role in elevating Qurmangazy’s küis to prominence throughout the Soviet Union, ensuring his name was featured in Soviet musical literature and encyclopedias. It was Zhubanov who compiled Qurmangazy’s works, transcribed them into musical notation, and authored a monograph on the composer’s life and work, referring to his legacy as the golden treasury of national music. Zhubanov also founded an orchestra of traditional instruments and was the first to perform Qurmangazy’s works in an orchestral format.

Akhmet Zhubanov. 1946, Almaty / CSA FPD RK

Among Soviet-era researchers, P. Aravin stands out for his detailed biographical study of the great küishi, based on archival materials, published in 1961 in the Bulletin of the Academy of Sciences of the Kazakh SSRi

It is essential to remember, however, that Soviet scholarship was shaped by a class-based ideological approach, which often cast historical figures through the lens of conflict between the rich and poor. As a result, most publications from that period emphasized that Qurmangazy was a witness to the uprising led by Isatai Taimanuly and Makhambet Otemisuly, that he was persecuted by the ruling elite, and that he suffered both exile and imprisonment.

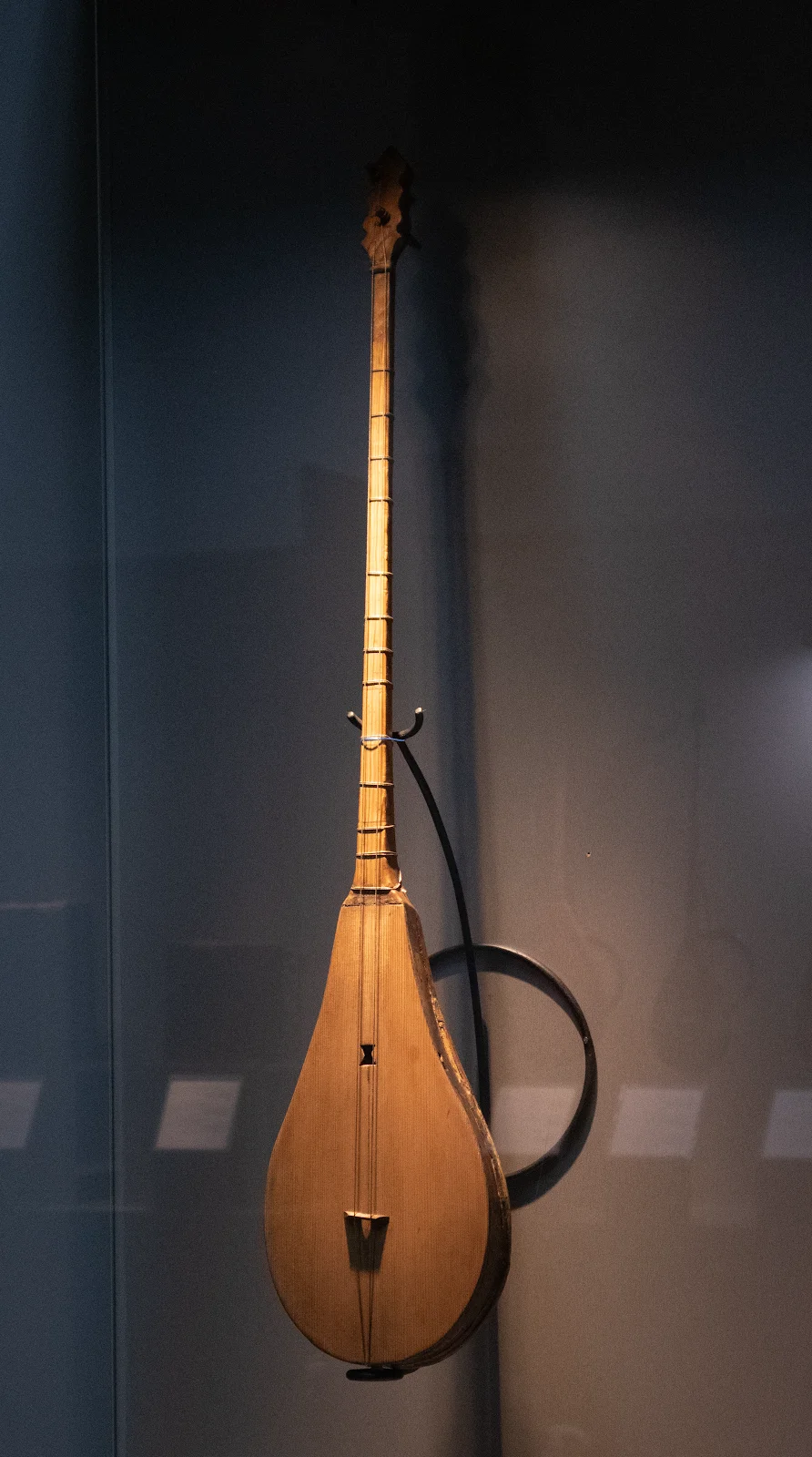

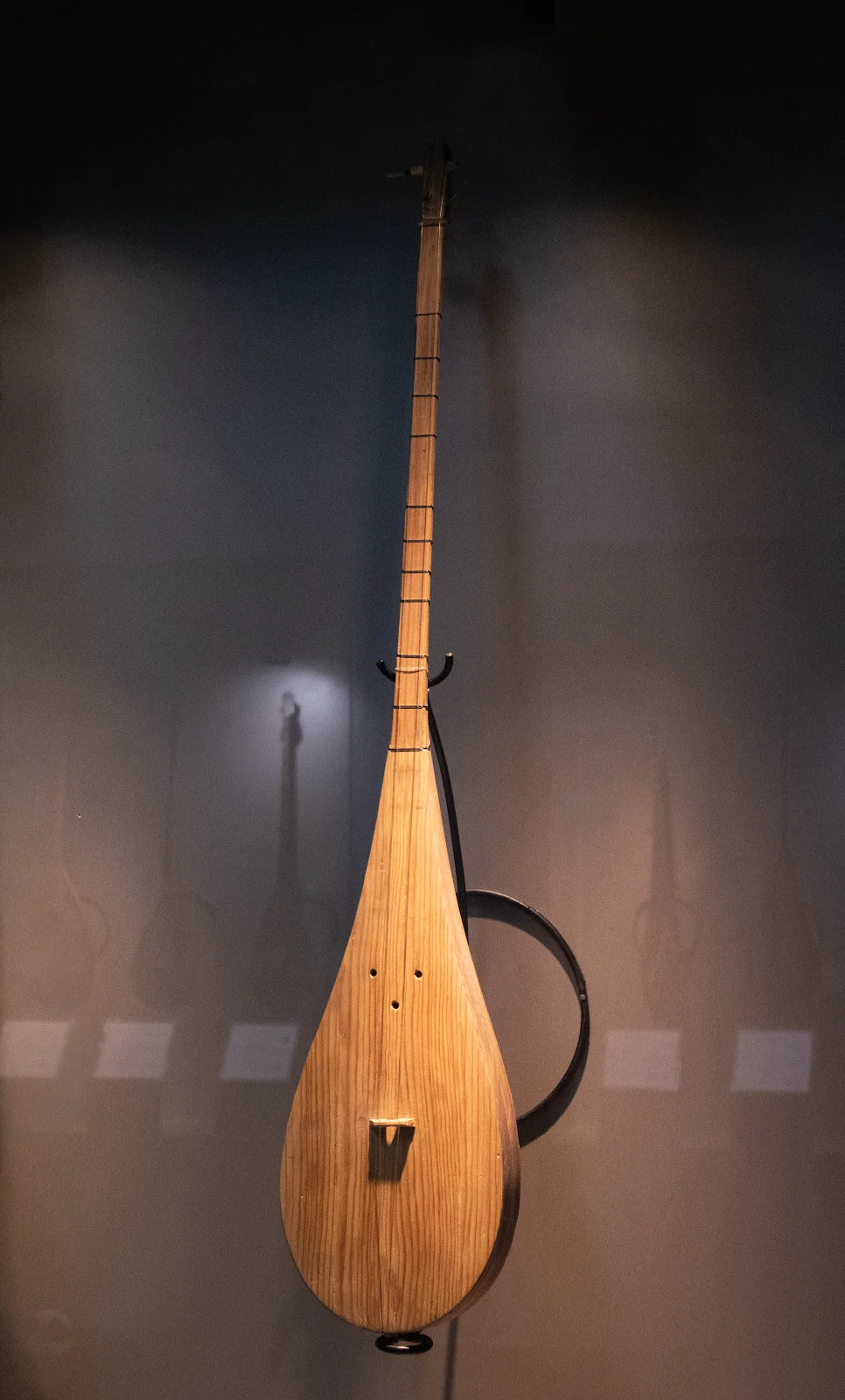

Dombra of Makhambet Otemisuly. Ykylas museum of national musical instruments / Qalam

Later Soviet studies also emphasized his resistance to tsarist policies, portraying the musician primarily as a symbol of anti-colonial struggle. Of course, these claims were not unfounded. However, when attempting to reinterpret the biography and works of the great küishi today, it becomes clear that such portrayals are insufficient. We must consider other aspects of his personality that go beyond the framework of ‘class struggle’. For instance, historical sources and Qurmangazy’s own repertoire show that he was a recognized master not only among Kazakhs but also among the Bashkirs, Nogais, Kalmyks, and even the Cossacks. Much about Qurmangazy’s life—his biography and the precise chronology of events—remains open to interpretation, and ongoing research is essential to shed light on these uncertainties.

Witness to an Uprising

To gain a deeper understanding of Qurmangazy as an individual, one must consider not only his musical legacy but also the historical context in which it was created. At that time, the political situation in the Kazakh steppe was extremely tense, and social contradictions were reaching their peak. Moreover, the Great Steppe, driven by technological progress and cultural exchange, was becoming a stage for global changes.

The changes were felt especially strongly when Jangir Khan, the son of Sultan Bukey, came to power in the Bukey Horde. In his effort to modernize the khanate, Jangir launched large-scale reforms and sought to introduce elements of European science and culture in education. He established new madrasa-style schools, organized a treasury and postal service, and through these reforms, ushered in a new chapter in the history of Kazakh society within the Bukey Horde.

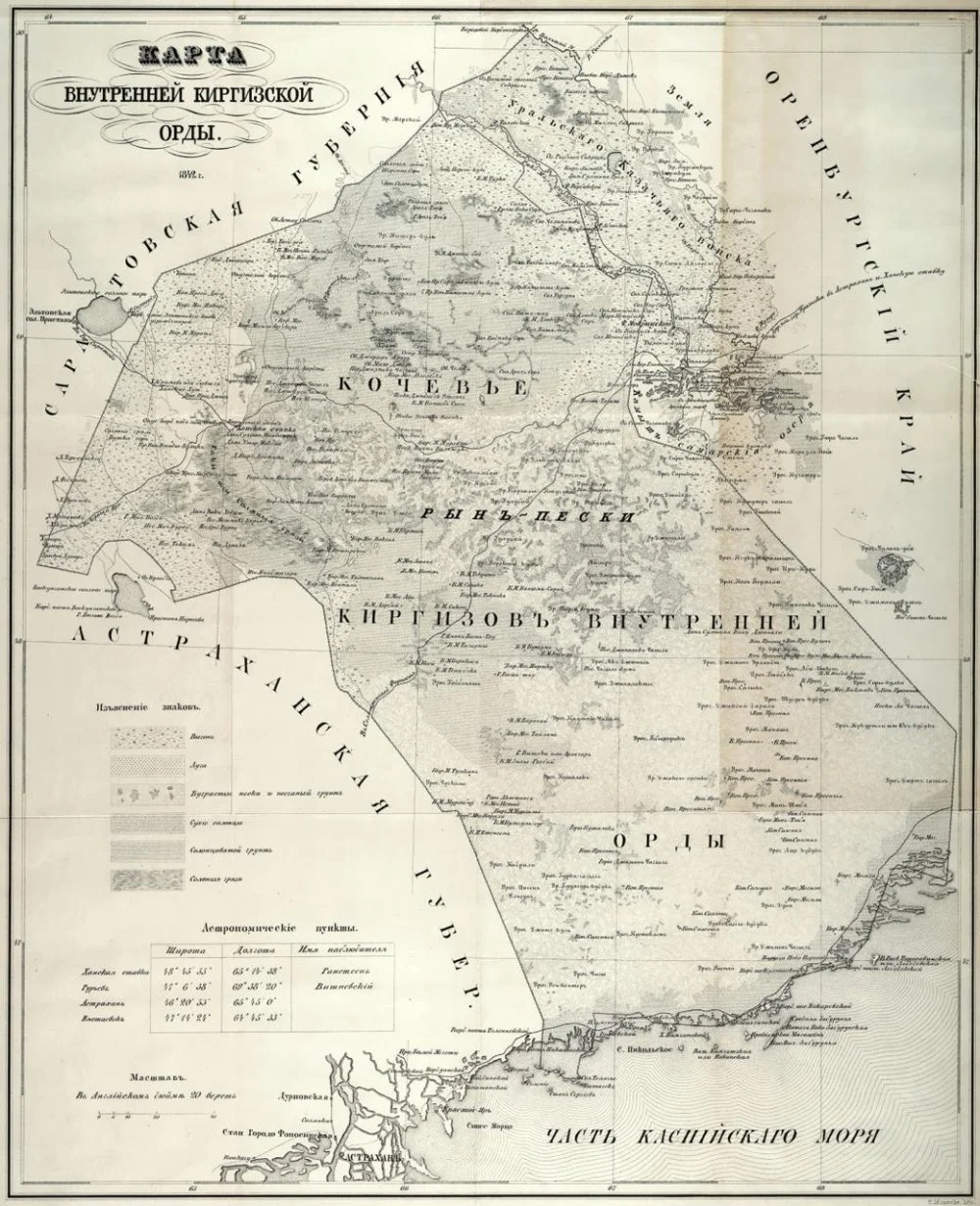

Map of Bukey Horde. 1842 / Wikimedia Commons

However, the khan's reforms failed to prevent a significant social divide, primarily due to his inability to resolve land issues fairly. When the ancestral lands of many clans were transferred to state control, conflicts erupted. The burden on ordinary people was further increased by the khan's taxes and the zakat (a mandatory annual tax under Islamic law). As a result, in 1836, an uprising broke out under the leadership of Berish clan elder Isatai Taimanuly and the aqyni

According to recent research, Qurmangazy was born in 1823 in the Bukey Horde in the locality of Jideli (now in the Jañaqala district of the West Kazakhstan Region), and when the uprising led by Isatai and Makhambet began, he was only thirteen years old.

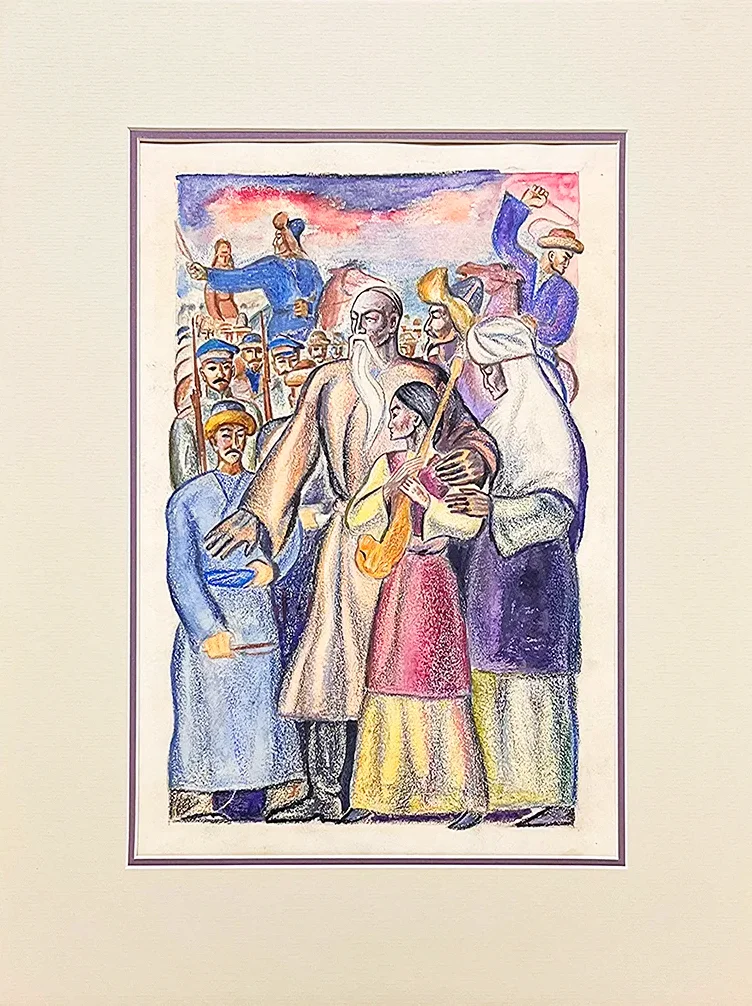

Isatay Isabayev. «Kurmangazy». Illustration for the book «My Kind Mother» by Saurbek Bakbergenov. 1966 / Bonart.kz

Young but deeply affected, he became a witness to events that would forever shape his consciousness.

That same year, 1823, Jangir Khan officially ascended the throne, ruling until he died in 1845. It was during this turbulent era that Qurmangazy came of age—not only as a musician but also as a person with a strong civic awareness. His formative years coincided with a time when the steppe was engulfed in a struggle for national liberation and calls for change echoed across the land.

These events found expression in Qurmangazy’s famous composition Kishkentai, which is essentially a musical poem, a complex work that weaves together several storylines and captures the emotional depth of a turbulent era. The voice of the dombyra echoes with the sorrow of a people mourning Isatai and Makhambet—a haunting cry of grief for those who sacrificed their lives in the fight for freedom. This was an extremely personal experience for Qurmangazy as his own family and loved ones endured the horrors of that time.

The trauma of that period left a lasting mark, one that continued to weigh heavily on future generations, and through his music, the great composer transformed the collective pain of his people into a monumental musical epic. His compositions do more than reflect the tragedy of the Bukey Horde—they give voice to the suffering of the entire Kazakh nation, preserving its memory in sound.

Was Qurmangazy a ‘Rebel’?

For a long time, it was widely believed that true professional art only came to the Kazakhs after the October Revolution, with the rise of Soviet cultural institutions. But history tells us a different story. On 27 October 1868, the Ural Military Gazette newspaper published a travel article by historian and local researcher N. Savichev titled ‘From the Karmanovsky Outpost to Glininsky’. In it, the author describes with admiration his impressions of Qurmangazy’s music:

Sagyrbayevi

Yet it is absolutely clear that he has no knowledge of European musical forms or rules. In conclusion, Sagyrbayev is an exceptional musical talent. If he had received a European education, he would undoubtedly have become a star of the first magnitude in the world of musici

Savichev, who wrote such a professional musical analysis, was clearly no amateur.

Alexandr Zatayevich recording the melodies of a Kazakh folk singer / CSA FPD RK

In the 1920s, ethnographer A. Zatayevich transcribed Qurmangazy’s compositions into musical notation and shared his impressions of the composer’s work and personality. He held Qurmangazy’s music in very high regard, placing Kazakh küis on par with European symphonic music. Nevertheless, Zatayevich’s notes also reveal a dismissive attitude toward Qurmangazy as a ‘rebel’ during the tsarist era, sometimes characterizing the composer as:

Qurmangazy was a true raider and robber of the romantic kind—overall, a real daredevil. He didn’t live at home, but constantly roamed in search of adventure, riding on horseback with a dombyra slung over his shoulder …

If we compare the views of the two researchers, N. Savichev of the nineteenth century and A. Zatayevich of the twentieth, there is a clear contrast. Academician Akhmet Jubanov later criticized Zatayevich’s assessments by saying:

In his book 500 Kazakh Songs and Küis, published in 1931, A. Zatayevich included the musical notation of Qurmangazy’s küis and expressed some controversial opinions about him. Despite the errors and inaccuracies, it was the first material about the composer published during the Soviet era and, therefore, cannot be ignoredi

Despite some controversial assessments, Zatayevich’s musical transcriptions of Qurmangazy’s küis (Serper, Aksak Kiik, Kisen Ashkan, Oybay, Balam) and his musical analysis still hold great scholarly value. After all, he was the first professional researcher to document Qurmangazy’s creative legacy.

Qurmangazy and the Turkic World

Qurmangazy’s küis became the voice of freedom not only for the Kazakh people but for the entire Turkic world. Raised in the heart of the Bukey Horde, he grew up immersed in the traditions of its great dombyra players, having received the blessings of masters such as Sherkesh, Soqyr Esjan, Uzak, Jappas Baijuma, and Baibaqty Balamaisan. And even as he absorbed and revered their heritage, Qurmangazy did not follow a beaten path—instead, he created his own musical tradition.

His energetic and expressive playing style, along with his virtuoso command of the dombyra, seemed to make the instrument speak in a voice that seemed almost human. In moments of inspiration, the musical waves transcended the dombyra’s traditional limits, soaring from the middle and lower frets to the highest registers in a way no one had witnessed before. It was as if the dombyra itself had been transformed, capable of speaking, weeping, and rising in defiance through his hands.

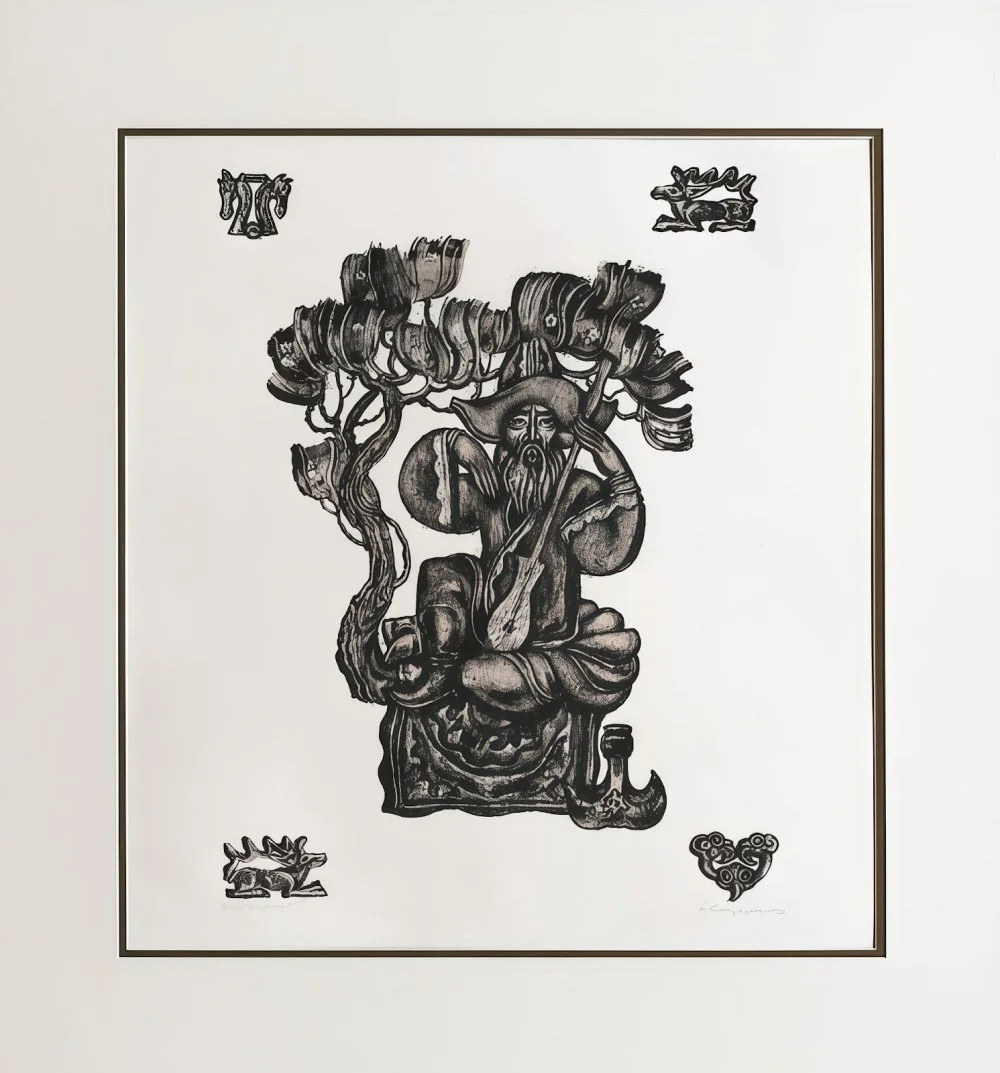

Yevgeniy Sidorkin. «The Storyteller» from the series «From the Darkness of the Ages». 1971 / Bonart.kz

Modern masters, while developing performance traditions, have yet to surpass the level set by Qurmangazy. Throughout the years in which he composed and played, he expanded the technical possibilities of the dombyra to such an extent that his compositional techniques remain virtually unchanged nearly two centuries later. His küis, taken together, are perceived as a unified epic narrative, where each composition sounds like a separate chapter in the chronicle of his native people’s fate.

And Qurmangazy’s work is widely known throughout the Turkic world even today. In 2018–19, concerts and major events dedicated to his music were held in several cities across Turkey. This is hardly surprising as Qurmangazy’s dombyra does not reject the musical characteristics of related peoples. On the contrary, Qurmangazy’s work echoes the tradition of the jyrau, the poet-singers who served as oral historians, storytellers, warriors, and spiritual guides in Turkic cultures. These artists preserved and passed down collective memory through song, blending the melodic influences of many cultures. Qurmangazy’s music carries that same spirit—deeply rooted in Kazakh identity, yet resonant far beyond its borders.

In particular, the folklore of the Nogais, Bashkirs, Tatars, Kalmyks, and Russians—who, for centuries, lived along both banks of the Volga and Ural Rivers—is very close to his work. Today, this is clearly seen in how dutar players in Uzbekistan, baglama masters in Turkey, and dombyra and topshuur players among the Buryats and Sakha in Russia perform Qurmangazy’s küis Adai and Balbyraun with skill and deep respect.

Qurmangazy’s compositions are vast in their scale. Using the language of European musical tradition, they can be compared to an ‘unfinished symphonic poem’. In musicology, his küis can be thematically categorized. For example, pieces related to freedom include Kishkentai, Adai, and Aqbai; those reflecting tragic personal events include Sheshem, Aman Bol, Kairan Sheshem, Itog, and Bozqangyr; and his beautiful küis Saryarqa and Alatau are dedicated to his native land.

There is a separate group of his works that was composed during imprisonment, and this group includes Kisen Ashqan, Turmeden Qashqan, Arba Soqqan, Erten Ketem, and Perovsky Marsh. Of course, this classification is conditional and serves only as a tool for a deeper understanding and study of the rich content of Qurmangazy’s küis.

Qurmangazy’s Dombyra

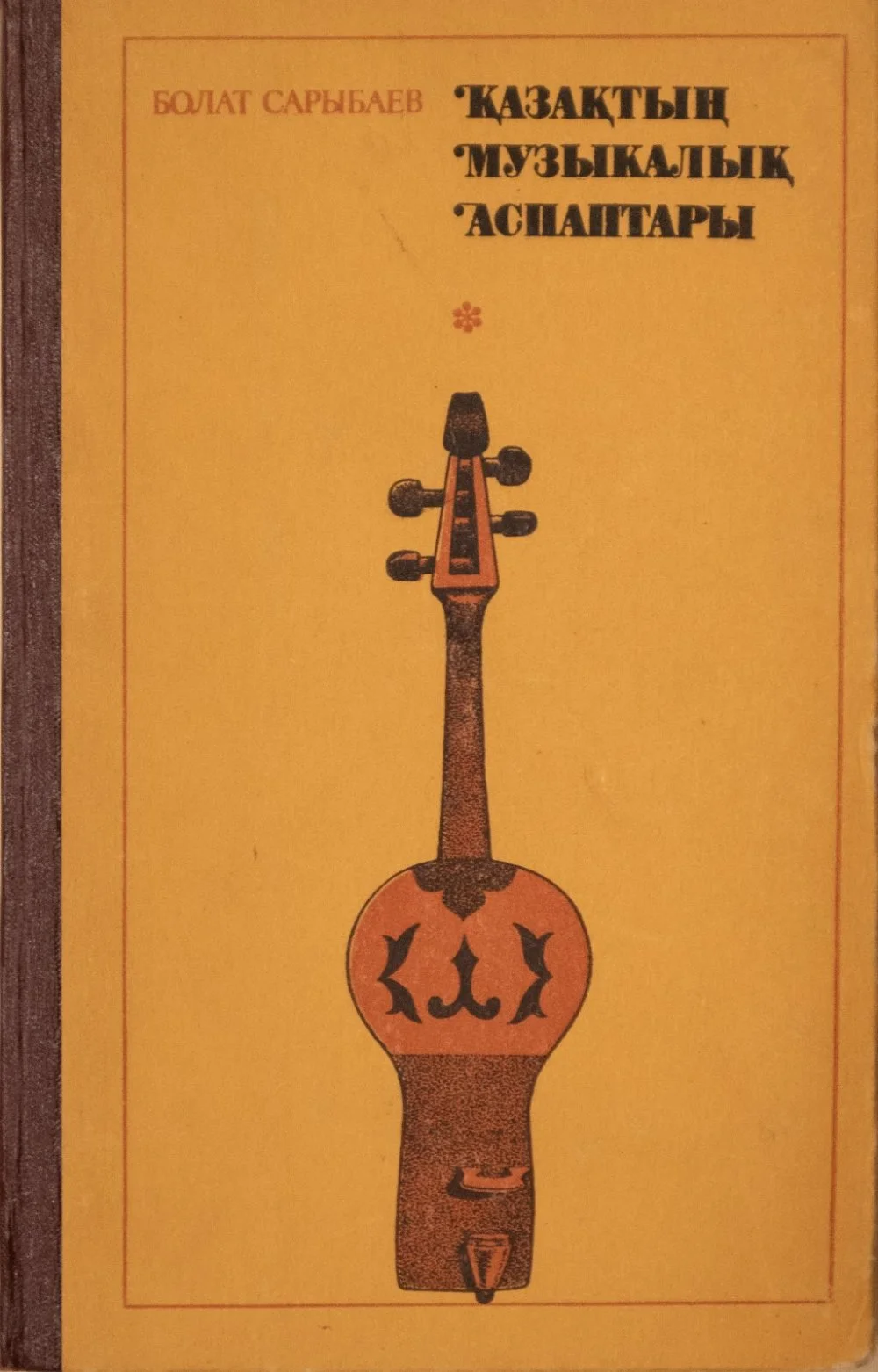

When discussing Qurmangazy’s dombyra, researchers usually refer to the work of Bolat Sarybayev, who provided a detailed description of Kazakh folk musical instruments. According to him, there are more than twenty varieties of Kazakh dombyra. The instrument is classified into various types based on the shape of its body and neck, such as the three-sided Tumar dombyra with an amulet-shaped body; the Qazmoiyn, a dombyra featuring a slender, curved neck; the folding dombyra used by nomadic aqyns and the Sere, with its neck and body bent from a single piece of wood; the Sheshen dombyra from the Syr Darya region, which is carved entirely from a single piece of jida wood; the Adai Kesikbas dombyra with a short neck; and the eastern two-string dombyra known for its soft, muted tone.

The dombyra that Qurmangazy played is mainly found in western Kazakhstan. It has a long neck, a large soundboard, and an oval, pear-shaped body that can be either solid or constructed from separate pieces. According to researchers, Qurmangazy’s dombyra had significant technical advantages over other types of instruments. First, it had more frets. While a typical Kazakh dombyra usually has seven to nine frets, Qurmangazy’s had as many as fourteen. Evidence of this can be found in the dombyra of his famous student Dina Nurpeisovai

Copy of dombra of Kurmangazy Sagyrbaiuly. Ykylas museum of national musical instruments / Qalam

As Akhmet Jubanov notes, in addition to the traditional diatonic frets, Qurmangazy’s dombyra also featured special quarter-tone frets. For example, in the climax of the küi Saryarqa, a unique fret called saryarka was used, which is close to the note B-flat in sound. The use of this fret became something akin to Qurmangazy’s personal signature, emphasizing the emotional tone of his küis. Even today, one can hear performers playing Qurmangazy’s dombyra using this fret in old video recordings or audio archives.

Dina Nurpeisova playing dombra. March of 1951, Almaty / CSA FPD RK

Modern researchers studying Qurmangazy’s küis point out that his dombyra employed additional movable frets, and the total number of frets on the instrument was as many as nineteen rather than fourteen, as previously believed. This dombyra had enhanced acoustic qualities: its powerful sound could easily carry over a distance.

Dombra of Dina Nurpeisova. Ykylas museum of national musical instruments / Qalam

The timbre of Qurmangazy’s dombyra was soft and noble, confirmed by the velvety tone of the instrument played by Dina Nurpeisova. Despite their noble timbre, the küis were marked by powerful dynamics. The richness of playing techniques, broad range, and deep-rooted tradition endowed Qurmangazy’s music with a truly epic scope.

A Melody That Has Survived Centuries

Research into Qurmangazy’s creative legacy continues to this day. Thanks to the efforts of domestic musicologists such as Karshyga Akhmadiyarov, Karim Sakharbayev, Aytjan Toqtagan, and Murat Abugazy, rare and previously unknown variations of the great composer’s küis have been discovered in various archives and reintroduced into the Kazakh cultural space.

This scholarly revival has also inspired a wave of renewed performance across western Kazakhstan. In the Atyrau, western Kazakhstan, and Aktobe regions, local dombyra players are now reviving works that had long remained unperformed for ideological restrictions. Among these are unique küis interpreted by virtuosos like Yermek Kaziev and Edige Nabiyev. They have enriched the golden treasury of Kazakh musical culture.

In 2025, the landmark audio collection Asyl Mura was released, and for the first time, the public could hear original recordings of Qurmangazy’s heroic küis as they were historically performed. These rare sound documents, preserved in the holdings of the Altyn Qor National Archive, offer listeners a direct connection to the musical spirit of the great composer.

Remarkably, Qurmangazy’s music fits organically into modern soundscapes. His küis, familiar in traditional folk orchestra performances, are heard in pop arrangements and symphony orchestras today. Moreover, the works of the great küishi find a place in instrumental jazz ensembles and the repertoires of choral ensembles too. His creativity inspires not only musical groups but also artistic collectives.

All of this attests to the breadth and universality of Qurmangazy’s musical language.