Qurt is more than a staple of traditional Kazakh cuisine—it is a symbol of resilience and cultural identity and practices. And this dried, hard cheese has played a vital role in survival in the steppe, especially as the primary provision during the harsh winter. In this article, historian Aliya Bolatkhan examines sources from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries to trace how qurt was made and understood over generations, to assess its cultural and practical importance for nomadic peoples.

The Oldest Qurt

In 1947, while excavating a Pazyryk burial mound in the Altai Mountains, archaeologists made a remarkable discovery—a bag of ancient cheese left as a tomb offering. Amazingly, it turned out to be over 2,500 years old, and based on its form and composition, researchers believe that it was most likely a prototype of qurt—dried curds made for long-term storage. This find isn’t an isolated case. Chinese records state that as early as the first millennium BCE, nomads were already making kumis (fermented mare’s milk) and cheese. These accounts are supported by both archaeological and ethnographic evidence.

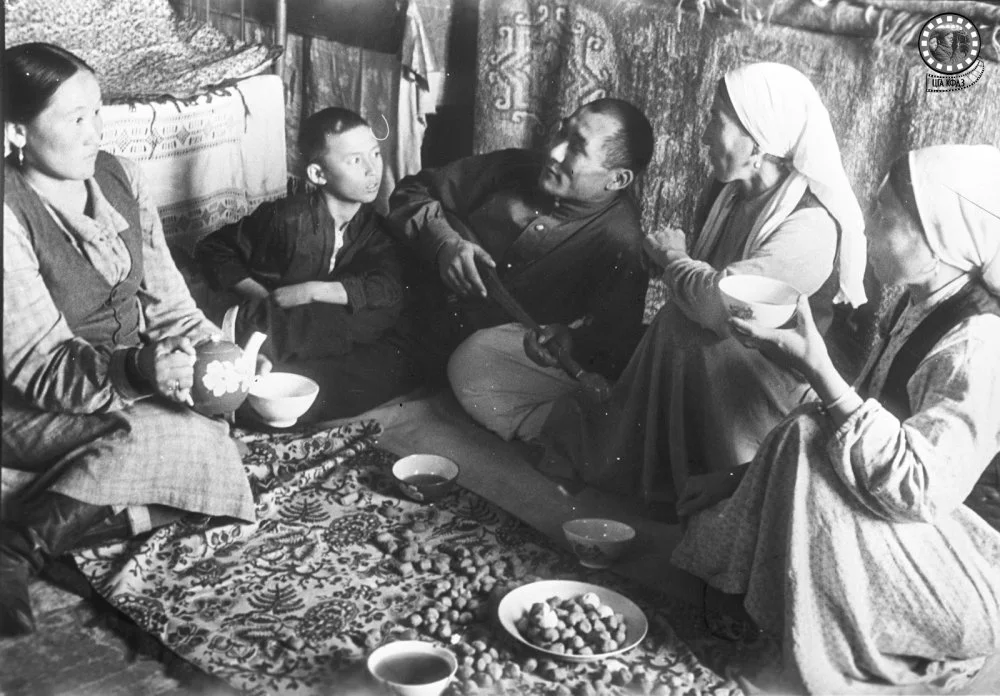

Mine hauler and Stakhanovite Bekturganov Zh. with his family. Achisai village. 1948 / CSACPSR RK

For the people of the steppe, qurt was not just food—it was a vital tool of survival in a harsh, unpredictable environment, its long shelf life making it ideal for their nomadic lifestyle. But don’t be fooled by its simplicity—behind each hard, white morsel was a labor-intensive process that required skill, patience, and a deep understanding of nature’s rhythms.

The Fermentation Process

The fermentation stage was crucial in the preparation of qurt and other dairy products. In traditional Kazakh households, both specific and non-specific starters were used.

Specific starters included airan (a thick fermented dairy product that can also be used as a starter for fermentation.), qymyz, süzbe (strained thick curds), and mäek (dried or fresh lamb rennet). Mäek was especially valued for its stability and ease of use: it didn’t need to be dissolved—it just had to be dropped into warm milk and removed once it began to curdle. Another advantage was that mäek could be stored in its dried form and used throughout the lactation season, the period during which livestock produced milk.

Several historical sources also mention unconventional methods of fermentation, using silver rings, coins, soot from smoked animal sinew, and melon seeds.

While not strictlyl enzymes, these objects acted as carriers of natural microorganisms capable of initiating fermentation.

The use of such non-specific starters often produced unpredictable results: the milk would curdle unevenly, or the process had to be repeated several times before it was successful. Gradually, as fresh portions of milk were added, the necessary microorganisms accumulated in the mixture, eventually forming a stable culture that produced more consistent results.

Woman making kurt (kurut). Pshart Valley in the Pamir Mountains, Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region, Tajikistan / Alamy

There are documented accounts of fermentation starters being passed down through generations, carefully preserved and protected. In every aul (village or community), people knew who had the most reliable airan with a strong, stable starter culture, and would turn to those women for a portion when required.

The Kazakhs developed several different methods for making qurt, each shaped by regional practices, available ingredients, and seasonal rhythms.

Producing the Main Mass of Qurt

The Airan–Irkyt Method

To make qurt, milk was first boiled and then cooled to a temperature suitable for adding the starter. Then, it was tightly sealed and left in a warm place for three to four hours. Depending on the ambient temperature, this would produce airan. It was consumed fresh and also used as a base for churning butter.

After the butter was churned from the airan, the remaining liquid was irkyt. This liquid was poured into a kazan (a large cauldron) and slowly boiled over low heat, constantly stirred until it thickened. The thickened mass was then poured into cloth bags and hung to allow the sary su (whey) to drain. What remained in the bags acquired a dense, curd-like texture and served as the base for qurt.

Akzel Beisembay. Qurt / Qalam

The Airan–Süzbe Method

There was also a way to produce qurt without the intermediate step of churning butter. The prepared airan, made as described above, was poured directly into bags and hung for one to two days to allow the whey to drain out. The result was a thick, concentrated curd-like mass called süzbe. It was consumed as a standalone product, and in some regions, it was called qatyq and used as the raw material for making qurt.

The Shape of Qurt

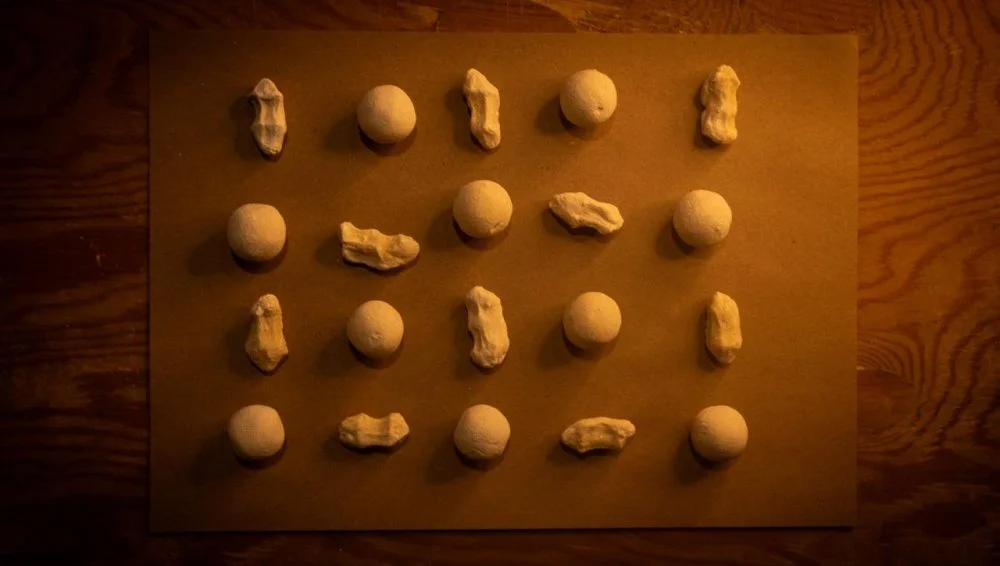

Once the thick curd mass was ready, drained of its whey and firm to the touch, the next step was shaping the qurt. Its final form varied depending on the intended use, regional traditions, density of the curd mass, and other conditions.

Akzel Beisembay. Qurt / Qalam

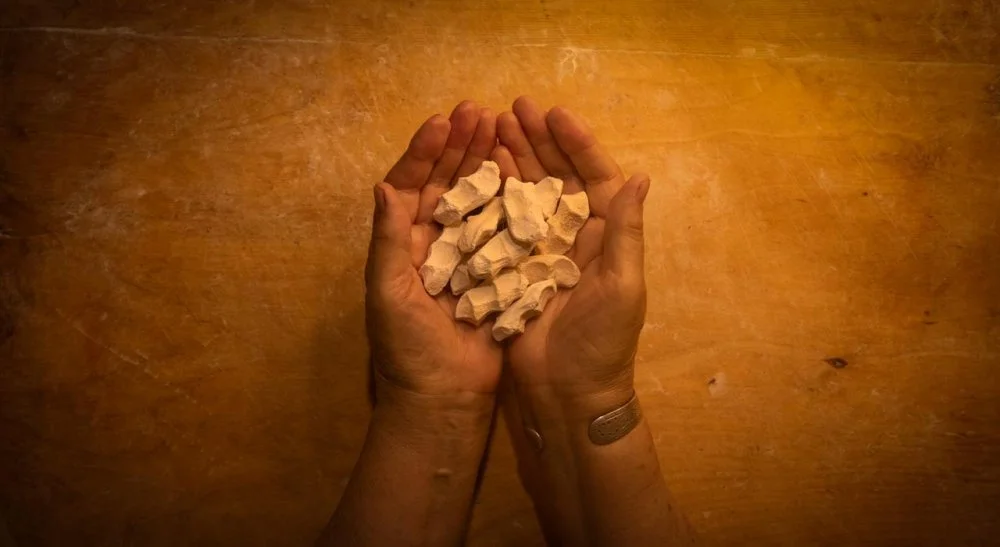

In the most common method, the mass was manually compressed in the palm of the hand. This type of qurt was known as syqpa qurt, derived from the word syqu, meaning ‘to squeeze’ in Kazakh. Syqpa qurt was recognizable from the visible fingerprints left on its surface, a reminder of the hands that had shaped it. It was most often served with tea and used either fresh or slightly dried.

Another popular form was döñgelek qurt, in the shape of small balls that were easy to dry and store in sacks. This type was typically made for long-term storage, especially for use during winter. There were also small irregular pieces without a defined shape; these were often prepared quickly and were meant mainly for dissolving in hot liquids such as water, sorpa (broth), or köje (a traditional soup among Kazakhs and Kyrgyz).

There was also a technique where the curd-like mass was spread into a large bowl and left to dry. A dense crust would form on the surface, which was then broken off by hand. This type of qurt was called a zharma qurt, the name coming from the word zharu, which means ‘to break off’ in Kazkah. This type of qurt was characterized by its gradual, layered drying process.

Akzel Beisembay. Qurt / Qalam

The process of shaping qurt was often a communal activity involving several women from the same family or aul. This fostered cooperation among women, sharing, and the preservation of traditions across generations. After shaping, the qurt was dried in the sun either on a tabaq (a flat wooden tray), on an öre shi (a mat woven from reed stems), or on special stands known as öre.

Varieties of Qurt

The wide variety of qurt shapes, textures, and preparation methods speaks to more than just practicality—it reflects a deep, regionally rooted system of traditional knowledge. This diversity of forms and preparation methods demonstrates how adaptable the traditional dairy production system was and how influenced it was by environment, lifestyle, and local custom. For example, in Zhetysu, a method of cold preparation known as tuzdalğan qurt was common—here, the thick curd mass wasn’t boiled but simply drained of whey and shaped.

Ethnographic studies of the Soviet period repeatedly noted that the kurt was used in rituals associated with wishes for fertility (shashu), taken on journeys and presented to elders.

If we try to classify the various forms and preparation methods of qurt, several distinct groups emerge based on their ingredients, preparation methods, shaping methods, fermentation styles, and seasonality. Each type reflects a different stage of milk processing and offers unique flavors, textures, and uses, demonstrating the versatility and resourcefulness of traditional Kazakh dairy-making.

By Base Product

-

Qurt made from irkyt, the buttermilk left after churning butter from airan or qatyq

-

Airan–süzbe qurt, made from thick, strained curds

-

Ashy qurt, a tangy, sour variety made from highly fermented airan

By Preparation Method

-

Qainatqan qurt, produced by prolonged boiling of the mass

-

Tuzdalğan qurt, or salted qurt, which was pressed and dried without processing by heat

-

Jarma qurt, which was dried in layers, with the top crust broken off

By Shaping Method

-

Syqpa qurt, formed manually by squeezing in the fist

-

Döñgelek, qurt shaped into small balls

By Seasonality

-

Winter qurt, usually döñgelek or jarma, was intended for long-term storage and eaten in winter with sorpa or köje

-

Qurt for tea, most often syqpa, was served fresh or slightly dried and was typically consumed year-round

Why Qurt Is Not Cheese

In Russian-language publications from the tsarist and Soviet periods, qurt was often referred to as dried cheese. However, from technological, functional, and cultural perspectives, qurt is distinct from cheese. It is not made by curdling milk and allowing it to age, as is typical for most types of cheese. Instead, it is produced through prolonged evaporation and drying. It does not undergo fermentation in the classical sense, nor does it ripen. Its primary purpose is utilitarian rather than gastronomic: it is designed to be stored for long periods without spoiling, regardless of living conditions.

Women selling kumis and dry salty kurt at road side stand near Altyn-Emel National Park, Almaty region, Kazakhstan / Alamy

Many sources have noted that qurt was valued for its nutritional content and antiseptic properties. It was said to ‘prevent scurvy’ and was used to treat gastrointestinal disorders. For stomach pain, a solution of qurt in hot water was prepared—a rich, warming, and soothing drink. Some sources report that it could replace tea and serve as a dietary food during recovery from illness. Qurt also served a deep cultural purpose: Soviet ethnographic studies have frequently highlighted that qurt was used in shashu events (fertility rituals), taken on journeys, and offered to elders.

Qurt: Past and Present

The qurt we know today is the result of many years of transformation, shaped by both technological advancements and lifestyle changes. One of the key shifts came with the introduction of cream separators, devices that began to be used widely in Kazakh households in the 1920s as part of agricultural modernization.

Before that, butter was separated by hand, churning airan or qatyq in large leather bags. This process preserved a specific structure in the curd: some fat remained in the mass, giving qurt its softness, richness, and balanced flavor.

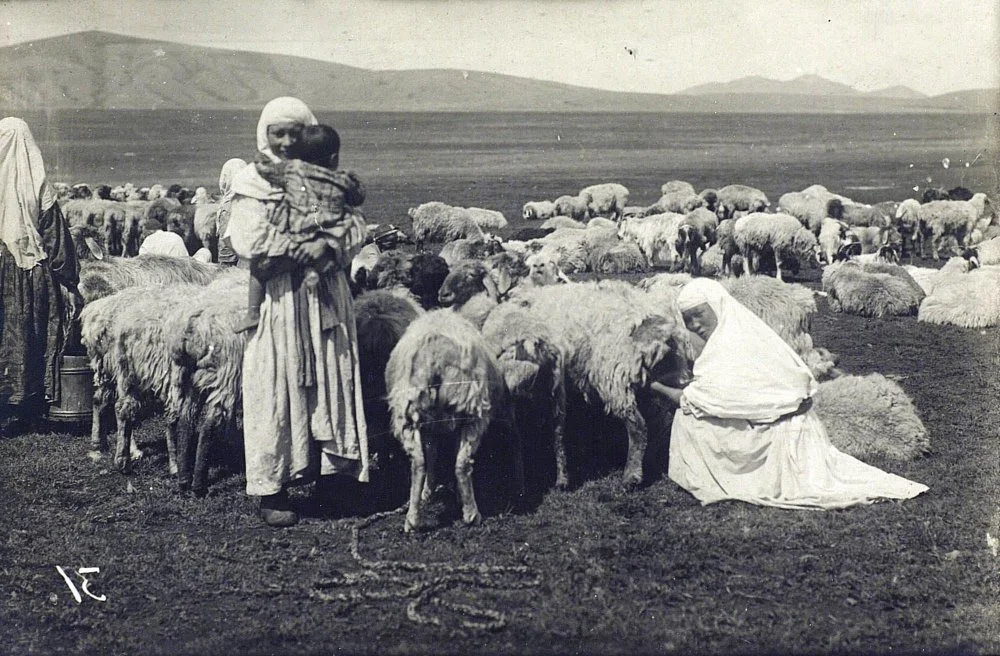

Samuil Dudin. Photo from the album «Kazakhs of the Semipalatinsk Region». 1899 / romanovempire.org

However, with the introduction of the separator, the resulting milk was almost completely skimmed. As F. Fielstrup noted back in 1927, qurt made from such (skimmed) milk became especially hard, darker in color, and slightly bitter in taste. It was served with tea less frequently and was more often kept as a strategic reserve for winter.

Until the early twentieth century, sheep’s milk was the foundation of dairy production among the Kazakhs. It was used not only to make airan and qatyq, but also to prepare winter reserves in the form of large blocks of qurt kesek, intended for long-term storage in the harsh steppe environment. Sheep’s milk is thicker and fattier than cow’s milk, with a fat content that can reach up to 9 per cent. Qurt made from sheep’s milk was thus more delicate, higher in calories, and more highly valued. According to a 1922 Soviet expedition, cow’s milk made up only 10 per cent of the milk consumed by a Kazakh family, while sheep’s milk accounted for over 30 per cent. In fact, in poor nomadic households that did not raise cows or mares, sheep’s milk was the dietary staple.

Akzel Beisembay. Qurt / Qalam

Today, the recipes, technology, and everyday practices surrounding qurt have undergone significant changes. While it has lost its status as a strategic survival food, it has not disappeared from Kazakh culture in any way. On the contrary, it continues to hold deep symbolic meaning, serving as a powerful, constant link to heritage, identity, and ancestral knowledge.

In homes, markets, and cultural festivals, qurt is still proudly prepared and shared, not just as food but as a story passed down through generations. Its presence reminds Kazakhs of their nomadic roots, their resilience, and the intimate bond between land, livestock, and livelihood. This is where its true value lies.