Central Asia, the cradle of ancient traditions and a crossroads of diverse ideologies, cultures, and beliefs, has long captivated the imagination of travelers from both near and far. Through their detailed notes and vivid reflections, they have, for centuries, offered a unique, albeit not always impartial, glimpse into the rich mosaic of life in this region: bustling bazaars, nomadic customs, and enduring cultural heritage. In this series of articles, Qalam presents excerpts from their accounts and memories, spanning different eras and revealing the many facets of Central Asia.

Today, we bring you the observations on the Kyrgyz by the renowned English traveler Annette Meakin.

Annette Meakin (1867–1959), a renowned English traveler and women's rights activist, was not only the first Englishwoman to journey to Japan via the Trans-Siberian Railway (then known as the Great Siberian Route) but also an astute observer of the lands she traversed. A significant portion of her journey took her through various regions of Central Asia, which she documented in her 1903 book, In Russian Turkestan: A Garden of Asia and Its People. Her travel notes include many observations about the Kyrgyz people, whom she often compares to other groups in the region.

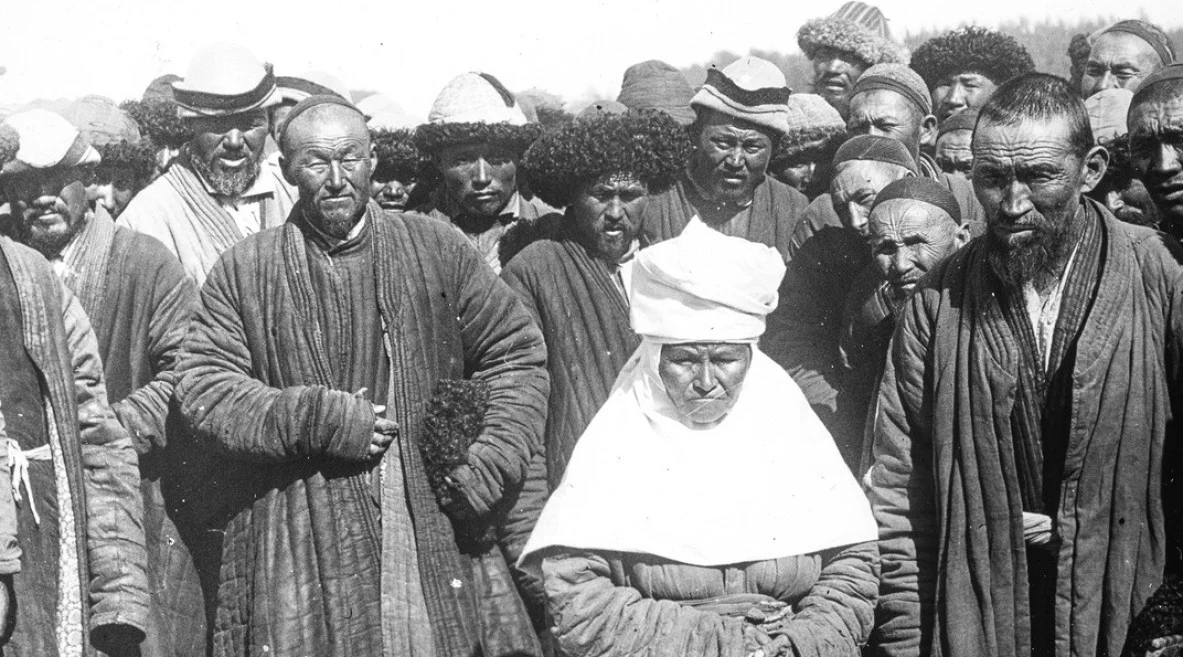

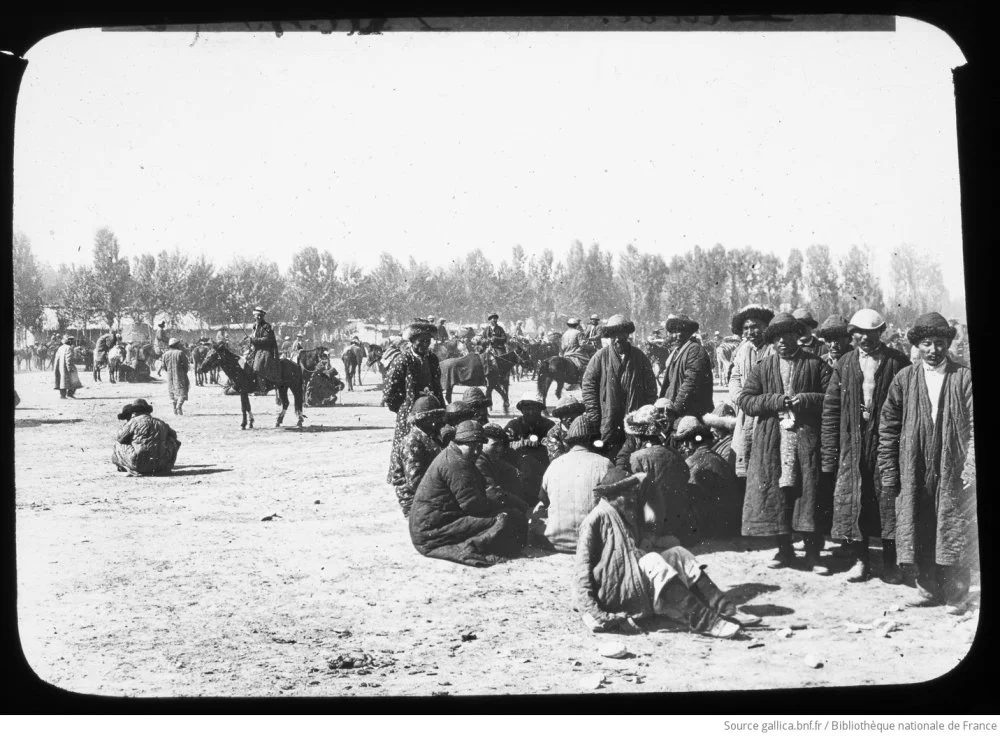

Paul Labbé (1867–1943). Waiting for the court decision (Pishpek), 1897 / Source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Like all European travelers who found themselves in the region, Meakin, of course, reflects on the ‘origins’ of the Kyrgyz:

The Kirgiz spring from the same stock as the Uzbegs; or rather they are Uzbegs who have remained nomads. Russian ethnographers divide them into two classes, the dwellers in the mountains and the dwellers in the plains. The former are called Kara-Kirgiz, and the latter Kirgiz-Kaizaks. Wandering amongst the mountains and rarely coming in close contact with other races, the Kara-Kirgiz have naturally retained a greater purity of type than their cousins the Kirgiz-Kaizaks, whose life in the plains keeps them in comparatively close relationship with the sedentary population.

Meakin does not overlook the topic of women in her observations:

Among these people great respect is shown to old men; and women, though they have to work hard, have a far more important position in the household than Sart women. A reason assigned for their custom of polygamy is that one wife would find it so hard to put up a yurtai

She also notes the peculiarities of Kyrgyz religiousness:

The Kirgiz are followers of Islam; some writers affirm that the Russians, finding them without any religion at all, introduced Mohammedanism as the faith most likely to suit them. Others say that they were Mohammedans before, and that the Russians only encouraged them. One thing, however, is clear: they are the least fanatical of all the Prophet's followers. This may arise from the fact that they can neither read nor write, nor worship in a mosque except when they come into the towns. In spite of all these disadvantages, their private life is infinitely more moral than that of the fanatical Sarts. Town life has a corrupting influence in Central Asia as elsewhere. The Kirgiz are an honest people.