In the 13th–16th centuries, the Delhi Sultanate flourished on the territory of India—a large and powerful Muslim empire whose rulers were generally of Turkic origin. Like all medieval states, life in the sultanate was tumultuous, filled with palace intrigues, coups, and wars. And if you think that succession to the sultan’s throne was limited to the eldest son, you are mistaken: even a former slave or a woman could ascend the throne. It is the story of such a woman, descended from Kipchak nomads and who became a sultan, that we wish to tell now. She was called "sultan" and not "sultana" or "sultaness" because she was a full-fledged ruler, not merely the wife of one.

Father – Nomad, Slave, Sultan

The third ruler of the Delhi Sultanate was Shams-ud-din Iltutmish ibn Yalam. He came from a noble Turkic family of Kipchaks but was captured and sold into slavery at a young age. He was bought by the first Sultan of Delhi, Qutb-ud-din Aibak, who himself had risen from slavery to the heights of power and valued intelligence, talent, and organizational abilities above all in those around him. Iltutmish possessed all these qualities in abundance, which allowed him not only to become the governor of the Badaun district but also to marry Aibak's daughter.

When Aibak suddenly died in 1210 during a game of chovgan (a kind of horseback polo), and the Turkic nobility of Lahore hastily placed his son Aram on the throne, the Delhi officials, dissatisfied with this decision, offered the throne to Iltutmish the son-in-law of the late sultan. Iltutmish marched on Delhi, defeated Aram-Shah's forces, captured him, and ascended the throne in 1211.

From then on, he tirelessly expanded the borders of the Delhi Sultanate, annexing more and more districts and cities. He created such a powerful army that even Genghis Khan's forces, approaching his northwestern border in 1221, turned back. In 1229, the caliph himself—the head of the entire Islamic community—recognized Iltutmish ibn Yalam as the sultan

Tomb of Altamash/Wikimedia Commons

When a Daughter is More Precious than Sons

The ruler’s family affairs were also going well: after his chief wife, Aibak's daughter Turkan Khatun, gave birth to his daughter Razia, his other wives bore him four sons. Iltutmish educated all his children equally, teaching them archery, horseback riding, military skills, governance, and the sciences. However, his primary support and heir to the throne was considered to be Nasir-ud-din Mahmud, his eldest son and the governor of Bengal. But Mahmud was not destined to become the Sultan of Delhi: he died in 1229, long before his father. The other two sons did not inspire much hope in Iltutmish, so he decided to leave the throne to his daughter, Razia. This was unprecedented in Indian history, and in general, Islam traditionally holds that a woman should focus on family and domestic matters. However, Razia had already proven her ability to rule wisely when, in 1231, the sultan left her in charge of the Delhi administration during his campaign against Gwalior. After seeing how brilliantly she managed her duties, Iltutmish ordered his officer, Mushrif-i Mamlakat Taj al-Mulk Mahmud Dabir, to prepare a decree appointing Razia as his heir. Historian Minhaj-i-Siraj wrote that the nobles questioned this decision, arguing that the sultan still had sons, but Iltutmish responded that he valued Razia’s abilities above those of his sons. We can only speculate whether this legend is true or was created by Razia's supporters during the struggle for the throne.

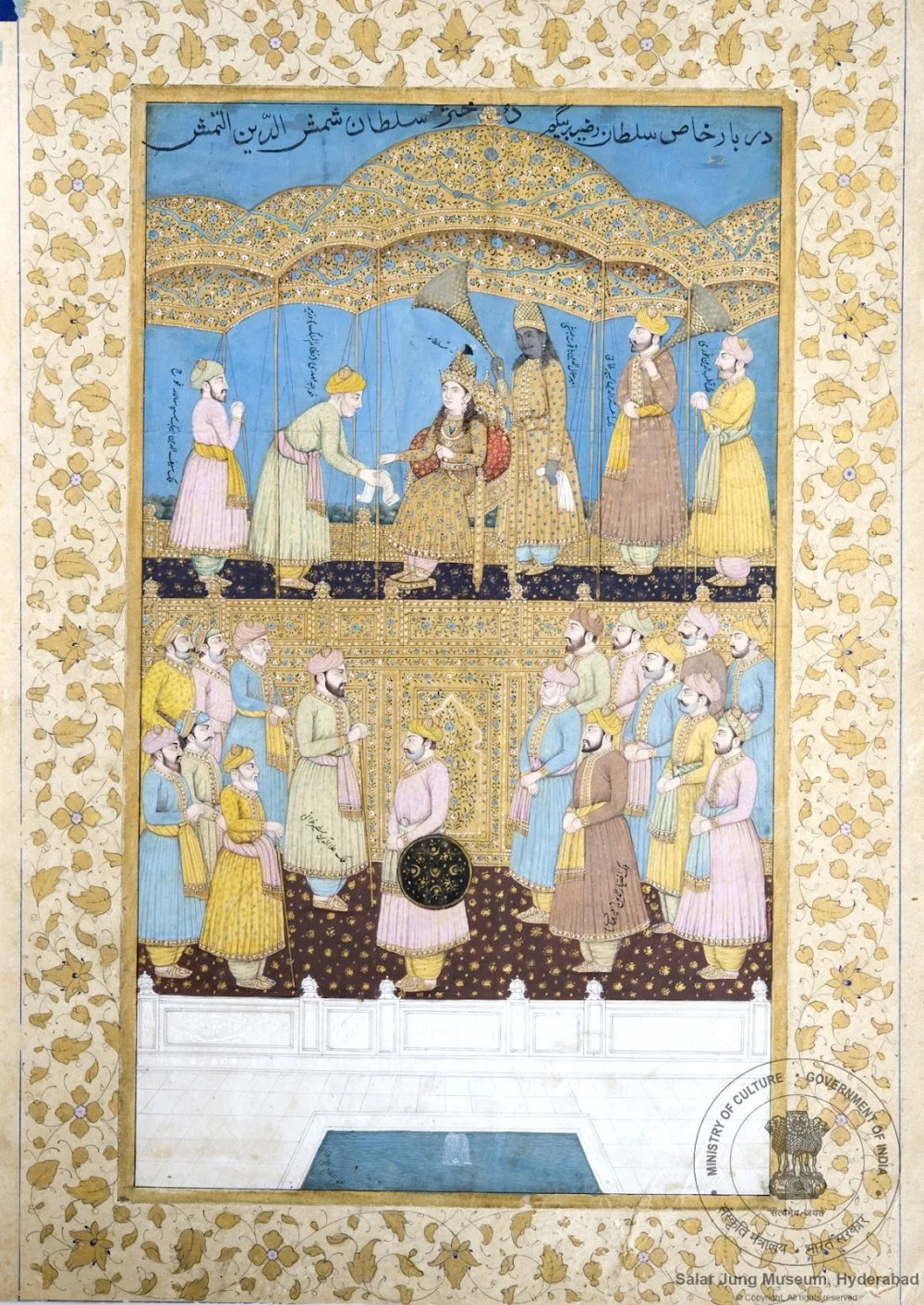

Miniature painting of Razia Sultana holding court ("durbar") with identifying inscriptions, by Gulam Ali Khan, circa 19th century/Wikimedia Commons

Family Matters

After a severe illness, Iltutmish recalled the eldest of his three surviving sons, Rukn-ud-din Firuz, from Lahore to Delhi. After the sultan's death, the nobility placed Rukn-ud-din on the throne, not even considering the possibility of recognizing a woman as the Muslim ruler.

Yet, the rule of the Delhi Sultanate still ended up in female hands. Rukn-ud-din Firuz was accustomed to living a carefree life and showed little interest in governing. However, his mother, Shah Turkan, although unable to become sultan herself, took control of the reins of power. With her blessing, one of Iltutmish's sons, who was beloved by the people—whether it was Muiz-ud-din, as the traveler Ibn Battuta claimed, or Qutb-ud-din Muhammad, according to other authors—was killed.

After the murder, a rebellion broke out in the country. Ghiyas-ud-din Muhammad, the second son of Iltutmish, raised an insurrection in Oudh. The governors of four provinces—Badaun, Multan, Hansi, and Lahore—also revolted. Bengal had already refused to recognize the authority of Delhi, and enemies invaded Punjab.

Whether he wanted to or not, Rukn-ud-din had to go to war. Meanwhile, his mother, Shah Turkan, plotted to kill Razia, who remained in Delhi. But Razia had no intention of dying. During Friday prayers, she addressed the people of Delhi with a speech. The Indian historian K. A. Nizami, in his work The Early Turkish Sultans of Delhi (1992), cites the 14th-century chronicle Futuh-us-Salatin, which states that Razia asked the people to overthrow her rule if she failed to meet their expectations.

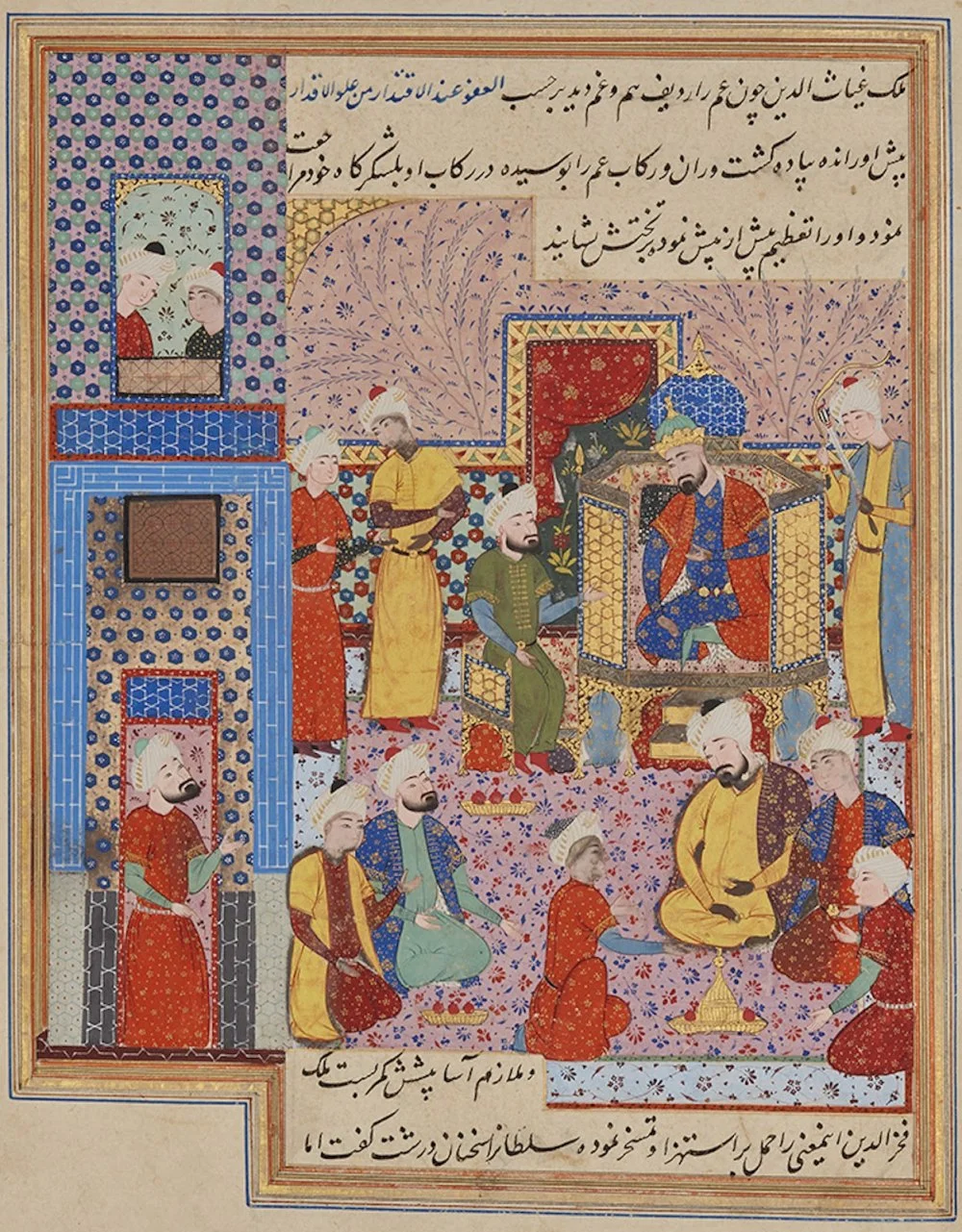

Banquet at King Ghiyath al-Din’s Palace, folio from a manuscript of Nigaristan, Iran, probably Shiraz, dated 1573-74/Wikimedia Commons

The people supported Razia. An enraged crowd stormed the royal palace and detained Shah Turkan. Several nobles and the main army of the state swore allegiance to Razia. Rukn-ud-din returned to Delhi but was captured—either by soldiers or by Delhi residents who stormed the mosque where he was hiding—imprisoned and soon executed after a reign that lasted less than seven months.

Adored by the World, Destined for Conflict

Thus, Razia, or fully Jalalat-ud-din Razia Sultan bint Iltutmish, became the first Muslim ruler in South Asia in November 1236. Her name was derived from the title Raziat-ud-Dunya wa-ud-Din ("Beloved of the World and Religion"). But she could not expect a peaceful and tranquil reign.

Rebels besieged Delhi from all sides. Razia's forces were insufficient. It seemed that the capital was on the verge of falling, and the power of the first Muslim sultan was about to collapse. But Razia was not only skilled in the art of war but also in diplomacy. She led her troops out of the city and set up camp on the banks of the Yamuna River. Her main goal was not to fight the enemy but to conduct secret negotiations. Eventually, the ruler of Lahore, Malik Izz-ud-din Kabir Khan Ayaz, and the governor of the Sadusan fortress, Malik Izz-ud-din Muhammad as-Salari, switched to her side. The remaining rebel leaders fled, but many of them were soon captured and executed.

Miniature painting of Raziа Sultana seated in a chair accompanied by attendants. Сirca 19th century/Wikimedia Commons

On Equal Footing with Men

The 13th-century Persian historian Juzjani mentions in his writings that soon, all the nobility from Gaur in the east to Debal in the west recognized Razia Sultan's authority. The ruler of Bengal voluntarily declared himself a vassal of Delhi. Yet, the Turkic nobles were displeased with how the sultan rewarded and elevated her supporters. Their particular anger was directed at the appointment of the Ethiopian Malik Jamal-ud-din Yaqut Hajib as Amir of Amirs—a position previously held only by Turkic military commanders.

The aristocrats who supported Razia hoped that she would become merely a nominal ruler, but her position grew increasingly strong. For instance, her first coins were issued with her father's name, but by 1237–1238, she began issuing coins exclusively with her own name. The 14th-century historian and court poet Abdul Malik Isami mentioned that she initially observed purdah (a moral-ethical code for the women of North India): a screen separated her throne from the courtiers and the public, and she was surrounded by female guards. However, at the moment of her ascension to the throne, Iltutmish's daughter was dressed in the traditional attire of a sultan, which had previously been worn only by men, and later, she regularly wore men's clothing, appeared in public with weapons, rode through the streets of Delhi on an elephant, personally led military operations, refused seclusion in the women's quarters, and interacted with men as an equal. She paid particular attention to the Delhi Sultanate's internal policies, focusing on education, medicine, science, and culture.

Hostility and Betrayal

Despite the genuine love the people of Delhi had for their just and talented ruler, Razia had many enemies: her efforts to break down the established norms of the patriarchal system offended conservative Muslims, who viewed her behavior as overly permissive and immoral. Razia faced particular opposition from the Shia community, which was significantly more radical than the Sunnis in India at the time.

On March 5, 1237, Shias attacked the main mosque in Delhi. Their leader, Nuruddin Turk, gathered about a thousand supporters from Delhi, Gujarat, Sindh, and Doab. They entered the mosque and began killing the Sunnis who had gathered for Friday prayers before the townspeople retaliated and slaughtered them in return.

In 1238–1239, Razia's former ally, the ruler of Lahore, Malik Izz-ud-din Kabir Khan Ayaz, rebelled against her. Razia's forces were victorious, and Izz-ud-din was forced to surrender and once again acknowledge Razia's authority. The sultan treated him leniently: she stripped him of his power over Lahore and reassigned him to a less significant post.

Razia returned to Delhi on April 3, 1240, only to learn that Ikhtiyar-ud-din Altunia, the governor of Bhatinda (Punjab), a former slave whom she had elevated, had risen against her at the instigation of the Turkic nobility. She set out on a campaign against him, but it ended in failure: the rebels killed her key supporters, and Razia herself was imprisoned.

When news of Razia's imprisonment reached Delhi, the local nobles placed her younger brother, Muiz ud-Din Bahram, the son of Iltutmish, on the throne. He ascended to the throne on April 21, 1240, and the nobles swore allegiance to him on May 5, 1240. The nobility intended to control the affairs of the state through the newly created position of Naib-i Mamlikat (Regent). However, shortly after ascending the throne, the new king ordered the Naib's execution to concentrate power in his own hands.

Marriage for the Sake of the Country and Death

After Razia's deposition, the Delhi nobles began dividing important positions and provinces among themselves, leaving Ikhtiyar-ud-Din Altunia, who had arrested Razia, without any significant role. Hoping to gain access to the throne, he freed Razia and married her in September 1240.

Since Razia was highly respected and loved by the people, several emirs who were dissatisfied with her brother as the sultan soon rallied to her support. Gathering an army, Razia and her husband set out on a military campaign against Delhi. Unfortunately, this campaign also ended in the defeat of Razia's forces—she and her husband were captured and soon executed. However, the traveler Ibn Battuta recorded a legend according to which Razia escaped the battlefield but was later killed in her sleep by a simple peasant who coveted her rich clothing.

«Razia Sultan» movie poster. 1961/From open sources

Legacy

Razia's reign lasted three years, six months, and six days.

The life and reign of Razia have inspired many writers and filmmakers. If you are interested in Razia Sultan's fate and the legends about her, you can watch the following films:

- - "Razia Sultana" (1961), directed by Devendra Goel.

- - "Razia Sultan" (1983), in Urdu, directed by Kamal Amrohi.

- - "Sultan Razia" (Razia Sultan), TV series – 2015, produced by Siddharth Kumar Tewary, Gayatri Gill Tewary, and Rahul Kumar Tewary.

REFERENCES

Синха Н. К., Банерджи А. Ч.. История Индии. / Перевод с английского Л. В. Степанова, И. П. Ястребовой и Л. А. Княжинской. Редакция и предисловие К. А. Антоновой. — М.: Издательство иностранной литературы, 1954.

Учок Б. Разия-хатун — султан Делийского мусульманского тюркского государства // Женщины правительницы в мусульманских государствах / Перевод с турецкого З. М. Буниятова, ответственный редактор М. С. Мейер. — М.: Наука, 1982.

Khan, Iqtidar Alam. Historical Dictionary of Medieval India. — Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2008.

История Востока. В 6 томах. Том 2. Восток в средние века. — М.: Восточная литература, 2009.

Клара Зармайровна Ашрафян. Делийский Султанат. — М.: Издательство восточной литературы, 1960.