In a course of lectures for Qalam, researcher Zira Nauryzbai delves into the mysterious world of Kazakh customs dedicated to the most important events in a person's life: birth, wedding and death.

In his research on Kazakh funeral customs, Ybyrai Altynsarini

In a mythological sense, a banner fluttering in the wind symbolizes the presence of a spirit, and a mourning banner carries the spirit of the deceased. Burning this banner signifies releasing the spirit (even if this idea was not consciously recognized during the Islamic period) and marks the end of mourning. Kazkah mythology also holds that in the afterlife, everything is the opposite of how it appears in the human world. The spear was broken so that it could serve its deceased owner—when an object is broken, its spirit is released, allowing it to join the spirit of the deceased.

The ritual of breaking the mourning flag is depicted in the film Qunanbai (2015, directed by Doskhan Joljaqsynov with the screenwriter Talasbek Asemkulov) in a scene during the asa (the annual day of commemoration or death anniversary) for Qunanbai’s father, Öskenbai. However, the film has an error: the flag is black, whereas Altynsarin notes that the color of the mourning flag depended on the age of the deceased. If a young person had died, a red flag was used, whereas a black flag was used for a middle-aged person , and a white flag was used for an elderly person. Obviously, there is a connection between these colors and the age of the deceased as well as the perceived weight of the loss.

The ethnographic encyclopedia Traditional System of Ethnographic Categories, Concepts, and Names of the Kazakhs (Qazaqtyñ etnografialyq kategorialar, ūğymdar men ataularynyñ dästürlı jüiesı, Almaty, 2011) highlights the existence of the concept of aq ölım, which means a righteous or literally ‘white’ death. This term refers to death by natural causes,i

Such a righteous death is the opposite of aram ölu, which is an impure or dishonorable death. Derived from the Muslim term ‘haram’, meaning forbidden by Islamic law, aram ölu applies to those who die during a theft or another crime, or who pass away in solitude without reciting the şahada.i

A natural death at an advanced age is also called aq būiryqty ölım (meaning ‘death by righteous decree from above’). This used to describe the passing of a person who has fully and honorably lived out the life allotted to them by the Almighty, serving as a good example for their descendants and those around them, and who has achieved their life's goals.i

Spirits of ancestors. Aruakhs/Beisembay Akzel/ Qalam

When an elderly person passed in peace and with honor, a white mourning flag would be displayed. Such a passing was not seen as a major tragedy, but was regarded as a natural transition, and the funeral commemoration was treated as a toi or a celebration. As my own grandmother explained to me in my childhood, it was only at these memorials that our relatives served sweets, and guests would take home sarqyt (leftover food) as a way to share in the longevity and the honorable life of the deceased.

Thus, it is easy to see that the concept of aq ölım, or white death, encompasses two forms: a natural death at an advanced age and a sacrificial death for a noble cause. Historically, this most often referred to death in battle, and one could assume that its symbol would originally be not the white flag but the ala bairaq, the red flag of a warrior. The color here did not symbolize age but the blood spilled in battle, the circumstances of the death, and even the deceased's status as a warrior. By the 1860s, however, when Altynsarin wrote his ethnographic work, this ancient symbolism had lost its significance. The Kazakhs had already begun to forget that for their ancestors, the most desired and honorable death was the one on the battlefield, witnessed by their comrades and liege lords.

As the Nogai-Kazakh warrior and poet Dospambet-Jyrau (fifteenth to sixteenth centuries) sang:

The enemy surges like a double flood,

An arrow pierces the side with a sharp thud,

The blood gushes out like a sagebrush bud,

The blood flows forth like a river's tide,

On the feathered steppe where the brave collide,

The batyr spares not his life to abide.

In Dospambet’s poetry, a glorious death in battle is valued just as highly as a good campsite, armor, a steed, food, and a beautiful wife:

Lifting my bow with high inlays,

I shot at the enemy, with no regret.

. . . In the sight of brave Mamai,

I became a martyr, with no regret.

In the epic Er Tarğyn, the renowned batyr (warrior) Tarğyn left his homeland because of a conflict and served first the Crimean khan and then another liege lord. His army was not composed of his kinsmen, and when, during a reconnaissance mission, he fell from a tree, injuring his spine and becoming paralyzed, his army abandoned him in the steppe. Only Aqjünıs, the daughter of the Crimean khan who had fled her father’s palace with Tarğyn, stayed by his side. She addressed Tarğyn, praising his boundless heroism, but delivered a harsh rebuke:

A hero who dies in disgrace,

Dies like a slave in servitude!

You were second to none of the batyrs,

Yet you perished in dust!

These sharp words from his beloved awaken a sense of honor and anger in the batyr. Overcoming his pain and fear, he forcefully stiffens up his spine and mounts his horse. For a warrior, only death on the battlefield is truly honorable—a glorious death that can only come in the presence of his comrades.

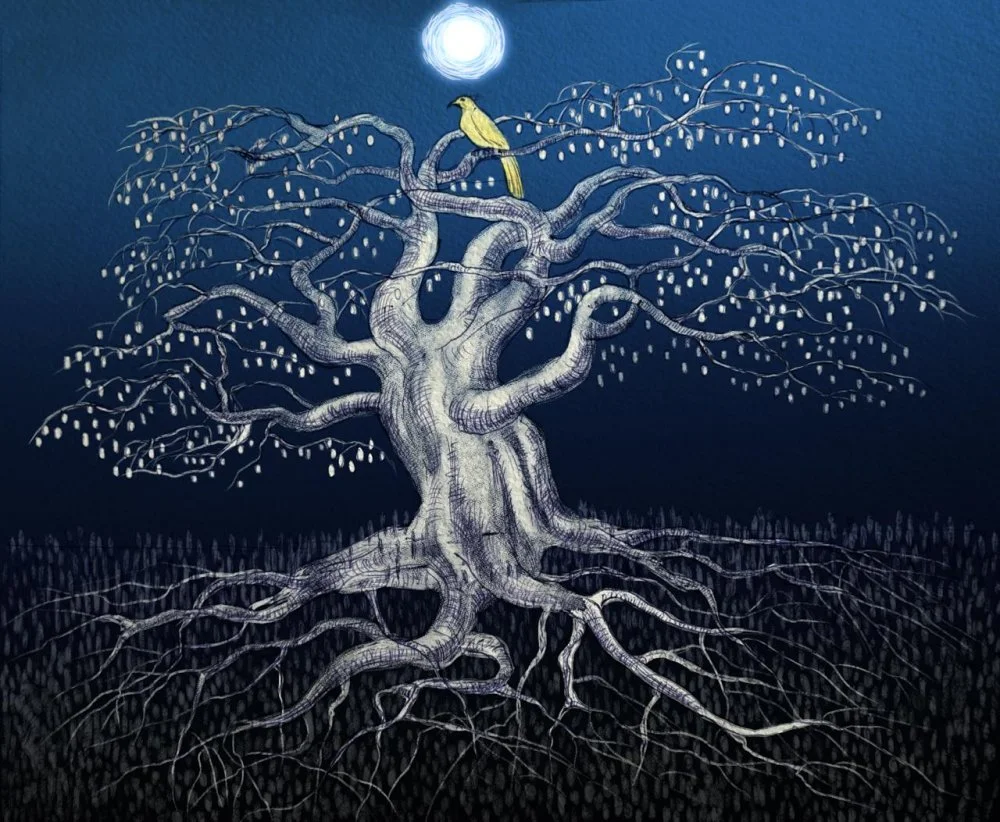

Mythological tree of life - Baiterek. Future lives grow on the tree in the form of fruits, living ones are near the trunk and dead ones in the roots/Beisembay Akzel/Qalam

The Mangystau Peninsula remained a frontier even at a time when the rest of the Kazakh population was living relatively peacefully under the Russian Empire. As a result, the traditional warrior ethos was preserved here longer. In 1855, a battle took place in the Karağan-Bosağa area between the Aday tribe and the Khivans. Qalniaz-Jyrau, who participated in the battle, immortalized it in the epic epos Baluanyaz Batyr. The story begins with a messenger’s report that a Turkmen detachment of 300 sabers, led by the notoriously cruel Böribaqy, had invaded Kazakh lands. Baluanyaz and the Kazakhs set out to meet them, but in their haste, they managed to gather only 60 sarbaz (warriors).

The epos (meaning epic tale or story) depicts how the alaman (raiders) of the Turkmen Yomud (jäumıt in Kazakh) tribe capture prisoners and hasten to retreat to their own territory. The Kazakhs warriors, in pursuit, draw so near that they hear the cries of the captured Kazakh women. Hearing their voices, Baluanyaz weeps.i

Old gravestone on the necropolises in Shakpak-Ata, Mangistau province, Kazakhstan/Alamy

In conversation, local historian Sultan Kadyr shared with me some of the orally preserved details of the battle that Qalniaz-Jyrau did not mention as they were so typical of that time. For example, after the battle, Batyr Turmambet approached his dying friend and said, ‘May your wound bring baiğazy, dear batyr!’ (‘Jara baiğazyly bolsyn, batyreke!’) Baiğazy is a symbolic gift given for viewing or a gift for a new item, usually given to children. In other words, Turmambet was humorously wishing his friend to receive many gifts from those who would see his wound.

Half a century after the battle, Turmambet, who had grown very old, found himself in the same place and loudly called out across the steppe to his friend: ‘O Baluanyaz, I helped your sarbaz achieve victory, and I helped you die with honor in battle. Why won’t you come and take me with you? Times have changed, morals have decayed, and I no longer want to live, tormented by the frailty of old age. If you are truly a batyr with aruaq,i

So what color was Turmambet’s mourning flag? Well, it was most likely white. And what color was the mourning flag of Qabanbai batyr, who was forced to mount his horse in battle at the age of seventy-eight? His final battle is described in several epic works.i

Mausoleum of Khodzha Ahmed Iassavi. Turkestan album/Wikimedia Commons

Of course, it is hard to say whether this epic is historically accurate. Folklore specialists and historians suggest that the image of the Kyrgyz batyr Sadyr has merged with that of another warrior, Qarabek. Moreover, there are several places in different regions of Kazakhstan and the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (People's Republic of China) which are considered to be the burial sites of the renowned batyr, commander, and saint Qabanbai. For us, the historical facts are not as important as the Kazakh perceptions of death. These perceptions were not unchanging; they evolved along with the historical situation:

Born a noble, the brave batyr

Will not age until he is ninety years old.

After the funeral (or, according to other sources, once the seven-day mourning period had concluded), the horse of the deceased, known as tūl at, was separated from the other horses, its mane and tail were trimmed, and the horse was released to pasture. This procedure was called tūldau. It was forbidden to ride the mourning horse or use it for practical purposes. During migrations, the horse was saddled backward, an action that was taboo in everyday life, covered with a mourning blanket, and had the clothing and headdress, whip, weapons, and armor of the deceased secured to the saddle. The widow or daughter of the deceased, dressed in mourning attire, rode ahead of the caravan with a mourning banner and led the tūl at by the reins. This custom is described in Mukhtar Auezov's novel The Path of Abai, where the young Abai encounters the mourning caravan of Bojei, who was a relative and rival of his father. It is likely that in ancient times, a doll representing the deceased was tied to the tūl at during migrations.

Old gravestone on the necropolises in Shakpak-Ata, Mangistau province, Kazakhstan/Alamy

On the last day of the annual memorial ceremonies, known as as, a horse was sacrificed after the horse race. There is still a belief among the Kazakhs that a devoted horse eagerly awaits its owner's death anniversary to reunite with him. Abylai Khan (an important Kazakh khan of the eighteenth century) is said to have composed a now-lost küi (musical composition) titled ‘Sūlu tory’ (Beautiful Chestnut). The legend of this küi is as follows: Jantai, a relative and companion of the batyr Bögenbay, was killed in an accidental skirmish after their victory over the Dzungars. When Abylai and his batyrs gathered for Jantai’s annual memorial, his chestnut horse galloped from the steppe and thrust its head through the door of the yurt. ‘You miss your master, and I miss him too,’ Abylai said and was inspired to compose the küi. The finest horses used in campaigns and battle by the batyrs, who were celebrated alongside the heroes, were called tūlpar; it can be assumed that this word is etymologically related to the concept of tūl, which can mean 'transformation' or 'completion' in Kazakh.

Funeral in Kordai district/Sputnik/RIA Novosti

The meat of the sacrificial horse was offered to the most respected individuals and those who participated in the memorial services. Some of the meat could also be left at the grave of the deceased. Thus, there is a clear continuity from the ancient custom of burying a horse (or horses) with the deceased to the medieval custom of laying a horse's hide over the grave and to leaving parts of the sacrificial horse's meat on the grave for passersby. An ethnographic encyclopedia describes a unique ritual from the memorial for Abul Khair Khan, where a spear lodged in the headrest was pulled out and meat was placed into the resulting hole. In this way, the meat of the sacrificial horse was used to ‘feed’ the deceased.

At the same time, there was a belief that the horse sacrificed during the annual memorial would accompany its master to serve him in the afterlife. Even today, if it is not possible to slaughter a horse for the funeral, relatives make an effort to ensure that a horse is sacrificed for the annual memorial service. This indicates that the ritual and its associated beliefs continue to exist.

Group of Kyrgyz (kazakh). Thomas Witlam Atkinson /Wikimedia Commons