The Janissaries, or ‘New Army’, were an elite unit of the Ottoman army for which handsome and strong Christian boys were selected from the Balkan provinces of the empire. In daily life they were similar to Sufi mystics, but on the battlefield, they caused terror and panic. Why did the sultans need these unusual and fearsome warriors? How did these young boys become Janissaries, how did they live and train, and why were they eventually disbanded? Qalam has the answers to all of these questions and many more.

This is the second part of our story about the Janissaries. You can read the first part here.

Sultan Murad I (1362–89) went down in history not only for establishing the Janissaries but also as the leader of a militant spiritual brotherhood known in Anatolia as Ahîlik (from the Arabic ahî, meaning ‘my brother’). It is said that this brotherhood was founded at the insistence of Hadji Bektash Veli (1209–71), a Khorasan Sufi and follower of the teachings of Ahmad Yasawi. It fought for the interests of the tanners’ guild and defended the common people against the Seljuks and Ilkhanids. The members of this brotherhood organized the coronation of Murad I in the field. Unsurprisingly, his new army of Christian boys was structured around the spiritual and moral paradigm of brotherhood.

Over time, the Janissaries became increasingly associated with the Bektashi Sufi order, which was founded by the same Hadji Bektash Veli and was close to Shi’ism. This led to the Janissaries being somewhat separated from the mainstream Muslim population of the Ottoman Empire. As a result, the Janissaries were often referred to as the Tâife-i Bektaşiye,i

Lambert Wyts - Agha of the Janissaries and a Bölük of the Janissaries 1573 /Wikimedia Commons

At the height of the empire, the Janissaries, like the Sufi brothers under Murad, played a key role in various ceremonies, such as the coronations of Ottoman sultans or the oath taken by the Şehzâde before he embarked on his first military campaign or left to govern a province. In fact, the sultans did not have a crown as such. The ceremony of elevation to the sultanate consisted of kılıç kuşanma.i

The bonds of brotherhood and Sufi solidarity would remain the foundation on which the entire structure, ethics, and hierarchy of the Janissaries were built. Sometimes, this was even more important than serving the sultan, whose slaves they were formally considered. The commander of the Janissaries was none other than the ‘agha’ or the Yeniçeri ağası, the ‘elder brother of all Janissaries’. According to Ottoman nomenclature, he was considered the head of all the ‘elder brothers’ of the Kapıkulu Corps (which included the cavalry, ‘gardeners’, et cetera), making him one of the most influential people in the empire along with the grand vizier. However, the grand vizier’s power often depended on the sultan’s will, while the Janissary agha was backed by the whole ‘gang’. Many viziers were often former janissaries, and this advancement in their careers only temporarily removed them from their brotherhood roots.

You’re Not Yourself When You’re Hungry

The Janissary Corps was called Yeniçeri Ocağı (the hearth), with the Kazan-ı Şerif (sacred cauldron) as its central and sacred object. They swore allegiance by the sacred cauldron; their rituals and ceremonies were built around it. Overturning the cauldron meant open disobedience, leading to immediate rebellion and beheadings. The entire structure of the hearth was also built around cauldrons: small, medium, and large. Every meeting, both general and company, of the Janissaries took place around the cauldron. Their main bond was preparing food together, and so it is unsurprising that the company commanders were officially called çorbacı, or those who make the soup.

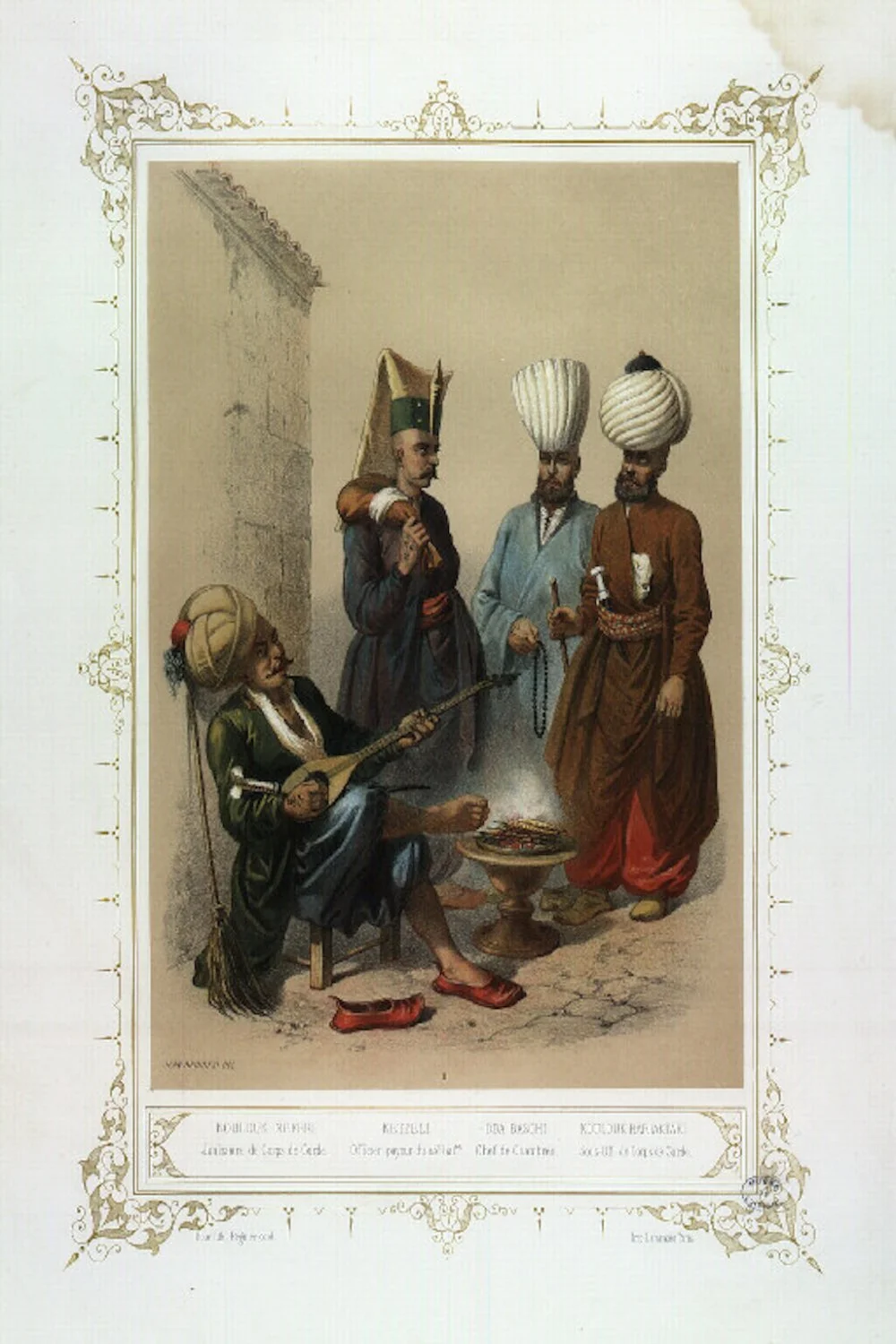

Chorbaji. From an 18th century Ottoman manuscript/Wikimedia commons

As the first permanent and professional army in modern history, the Janissaries were unique in that their only income was a fixed salary in peace and war. The Janissaries were entirely responsible for their own sustenance in peacetime, buying their own provisions and cooking their own food with their own money. By contributing themselves to the weekly purchase of meat, beans, cheese, and vegetables, they knew the pressures of inflation better than most, what corruption cost, what caused shortages, and how logistical problems or natural disasters affected prices. In any economic crisis, the Janissaries were eager for campaigns and war. After all, in times of war, they were supported exclusively by the treasury, which also paid a substantial sefer bahşişi.i

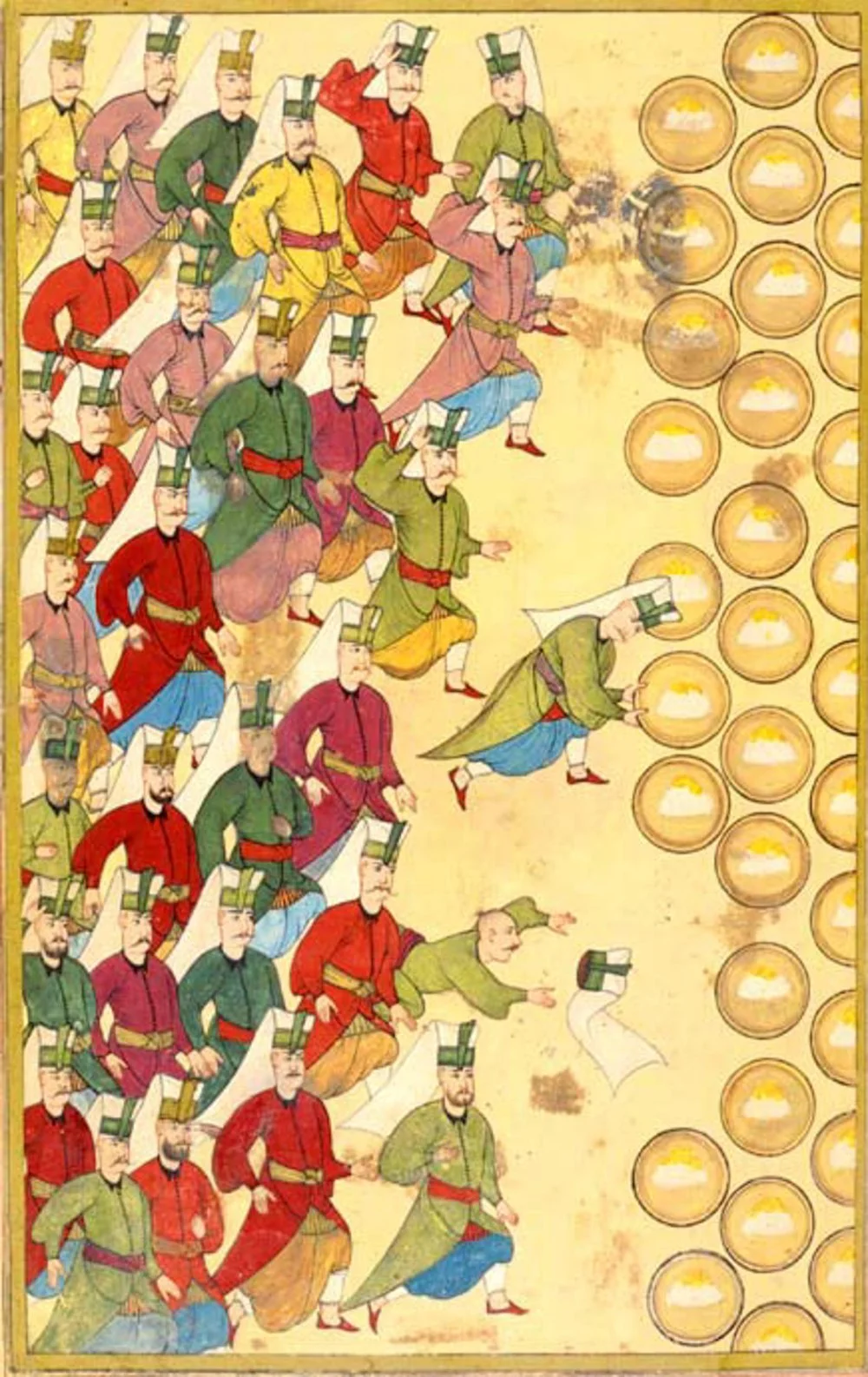

Banquet (Safranpilav) for the Janissaries, given by the Sultan. If they refused the meal, they signaled their disapproval of the Sultan. In this case they accept the meal. Ottoman miniature painting, from the 'Surname-I Vehbi' (Fol. 22b). Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi, Istanbul. 1720/Alamy

Since its inception, this fearless and brutal army, this Sufi citadel of mystical Islam, was known to be very greedy for money and, of course, food. The history of the rise and expansion of the Ottoman Empire, from Mehmed II the Conqueror (1444–46, 1451–81) to Mahmud II (1808–39), is a story of relentless mutinies by Janissaries dissatisfied with their wages, rations, or allowances. For every holiday and social event, the Janissaries had to be fed by the palace—and that’s tens of thousands of people—by sending them baklava and sweets from the sultan’s own kitchen. As expected, these ‘cauldron tippers’ also expressed their dissatisfaction with state policy through food—they refused to eat the soup offered to them in the palace.

The Secret Life of the Janissaries

We all know that even the daily diet of these elite Ottoman troops was much more sophisticated than that of their fighting counterparts in ancient Sparta. But if the Spartans were forbidden to eat with their wives to maintain morale—they could only eat with their fellow soldiers—the Janissaries were forbidden to marry. Thus, because of the prohibition on marriage, the Janissary Corps remained an all-male fraternity until the early sixteenth century. They had no wives, no children, and no ties to their original kin.

This, of course, brings to mind the Spartans, who, while being able to marry earlier, were forbidden to spend the night with their wives until the age of thirty in order to boost discipline, even though people in those days married much earlier and usually did not live long. A closer example is the spiritual and knightly orders of Western Europe,1

Sultan Osman II (Reigned 1618-1622) With His Vizier Davud Pasha In A Procession Of Janissaries And Guards/Alamy

These restrictions did not mean that the janissaries had no private life or love affairs, and sometimes, their carnal activities became the subject of controversy. However, it was dangerous to make open claims against the Janissaries. For example, Baron Václav Vratislav of Mitrovica, who accompanied the diplomatic mission of Emperor Rudolf II to the Ottoman capital in 1591, recalled the story of a young Turkish woman who, while her husband was still alive but quite old, secretly rendezvoused with Mustafa, a janissary, in a tavern after changing in the women’s bathroom. There are many stories of how Janissaries, despite the ban on marriage, had secret wives and children both in the capital and in the provinces.

Of course, the sex lives of the janissaries were not limited to permanent cohabitation, and the commercial pursuits of their sensual pleasures were known to everyone. In the seventeenth century, the Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi counted 200 brothels and taverns run by Greeks and Jews in the port areas of Galata, a district of Istanbul, alone, where the main customers were janissaries. It should be noted that sex workers were not exclusively owned by non-Muslims, and sometimes even former janissaries ran brothels.

The Janissaries did not only socialize with women, and this aspect of their life aroused great interest among ordinary people. We will not go into details, but their social circles also included young beardless hammam workers who worked as washers and other bath attendants, as well as the civelek acemisi (merry recruits), young men who helped the Janissaries in their daily lives to cook, tidy up, and clean clothes. They did not receive a soldier’s salary, but were allowed to eat and sleep in the Janissary barracks under the patronage of influential Janissaries. Interestingly, the famous seventeenth century Islamic theologian Vankulu Mehmed Efendi, known for his conservatism, openly accused the Janissaries of using these boys for sexual pleasure during campaigns.

The official celibacy of the Janissaries changed when an intercession was made for a janissary by his sensitive and highly influential brother.

Illustrated history of Turkish Army (Ottoman Empire). Harbadji (Halberdier). Janissary (Making Salvation). Janissary (In The Dress Of Selamlik). Solak (Soldier Of The Sultan's Guard Corps). Janissary (Bearing The Ulufe (Appinement))/Alamy

This brother was the Grand Vizier Yunus Pasha, who had a distinguished career, given that he had started as a poor Christian boy, rising from a mere recruit to become the agha of the Janissaries. The sultan appointed him to the imperial diwan, made him vizier and governor. Yunus Pasha even married the granddaughter of Sultan Bayezid II. He personally petitioned Sultan Selim I (1512–20) for permission for his not-so-young brother, who had also joined the ranks of the Janissaries, to marry. After several refusals, the sultan finally took pity on the janissaries and granted them permission, which in the long run, may have deprived the empire of its most effective troops. Initially, however, the Janissaries were reluctant to marry, and only did so at an advanced age as marriage prevented them from obtaining command positions in the army. But the situation changed, and over time, more and more children of janissaries were recruited into their ranks, especially orphans who were registered as kuloğlu,i

The Crème de la Crème

Strange as it may seem, when creating a large army of ‘rootless’ slaves, the Ottomans preferred boys from noble Christian families, and this choice was even enshrined in law. Therefore, devşirme did not apply to orphans, families with a bad reputation, the stunted, or those prone to baldness. Of two sons in a family, the healthier and more handsome one was chosen, especially for service in the palace, a practice that demonstrated that nothing had changed since the time of the Byzantine emperor Justin I (518–527), who was once a poor boy from the Balkan chosen for the palace guard because of his good looks. Among the most favored were the sons of priests and students of church schools, one of whom was the future Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, who would later build one of the most beautiful mosques in Istanbul, the Sokollu Mehmet Paşa Camii (Sokollu Mehmet Pasha Mosque). The architect of the mosque was Sinan, the greatest architect in the Ottoman Empire, also known as Sinan Agha, making it easy to guess that he was also a janissary of Anatolian Christian origin.

Sokollu Mehmed Pasha and Feridun Ahmed Beg circa 1568/Alamy

Grand Vizier Mahmud Pasha, who was accused of murdering the heir to the Ottoman throne, was, according to various historians, a descendant of the Byzantine aristocratic dynasty of the Angels (Angeloi), although he was born in a Serbian despotatei

A Poet’s Death—A Slave of Honor

Surprisingly, the world’s most efficient and brutal army, which cold-bloodedly slaughtered the Hungarian cavalry in a few hours at the Battle of Mohács (1526), was no stranger to romance and art, and the Janissaries’ contribution to Ottoman literature in general is quite distinguished. Whether it was a way to cope with the reality of their bloody profession or to cope with the rigid age hierarchy and humiliating hazing of their bachelor fraternity, or whether it was driven Sufi traditions, the Janissaries were known as good poets. Their pseudonyms evoked spiritual romance and worldly peace: Aşkî (Full of Love), Nihanî (Mysterious), Sıdkî (Faithful, Truthful). They wrote their poems not only in Ottoman Turkish but also in Persian.

Gentile Bellini. Turkish Janissary, 1479-1481/Alamy

Mahmud Pasha was generally considered to be one of the most influential Ottoman poets of the time, and he chose a heavenly pseudonym, Adnî,i

Jean Brindisi. Janissary plays music.1855/Wikimedia commons

I Begot You, and I Will Kill You!

From its inception, these elite ‘new troops’ of rootless, unmarried Christians played a crucial role in major political affairs. Mehmed II’s father, Sultan Murad II (1421–44, 1446–51), once relinquished the throne in favor of his son. However, a few years later, with the support of the Janissaries, he decided to displace his son and become sultan again. This trauma and mistrust of the Janissaries, who could so easily overthrow the power and authority of the sultan himself, may have led him to seek religious permission to kill his half-brothers for the sake of the Nizâm-ı Âlemi

Over time, the personal guard of the sultan grew into a huge army and attempted to influence the succession of the throne. It was they who executed the young Sultan Osman II (1618–22), who planned to reform the army of the Ottoman Empire, accusing the Janissaries of cowardice and inefficiency. They participated in the conspiracy and subsequent execution of Sultan Ibrahim (1640–48), deposed Sultan Mustafa I (1617–18), Ahmed III (1703–30), and indirectly assisted in the deposition or assassination of many other sultans. And the viziers and pashas who were killed or deposed are almost countless. In fact, they were responsible for many, many fallen heads.

Jean Baptiste Vanmour: The Murder of Patrona Halil and his Fellow Rebels. 1730

The number of Janissaries would steadily increase over time, reaching about 53,499 soldiers by 1670, with expenditures exceeding 21 per cent of the total budget of the Ottoman Empire.i

Many of them had nothing to do with military affairs, but continued to receive salaries, organize rebellions, and commit robberies. The recruitment of Christian boys had long since ceased, as had the killing of Şehzâdes, and the Janissaries settled down to family life, having children, who, in turn, entered the service. Most Janissaries were engaged in commercial activities, running a protection racket and pushing around merchants and the bazaars themselves. Most importantly, they could no longer fight properly, but they never stopped organizing rebellions and uprisings.

Hiob Ludolf. Death of vizier Muezzinzade Hafiz Ahmet Pasha during the Revolt of janissaries in 1632. 1701/Wikimedia Commons

The history of the Janissaries ended as tragically as it began. On 16 June 1826, Sultan Mahmud II, with the help of a European-reformed army with the symbolic name of the Nizâm-ı Cedîd (the New Order), simply cannoned away the barracks of the Janissaries, who had brought their cauldrons to the square for the last time as a sign of defiance. Thousands died in the shelling, tens of thousands of survivors were arrested and executed, and hundreds of thousands of former Janissaries tried to blend into the population, hiding their past for decades. Thus began a period in Ottoman history when men would suddenly gather in groups in Istanbul’s coffeehouses and taverns, drinking themselves into oblivion and tearfully singing their pitiful songs. There would also be those who would turn to a completely different path and start a new life in secret, for at the funerals of some Christian priests in the New World, the janissary tattoos were suddenly discovered on their bodies.

One way or another, the fate of one of the main brands of the Ottoman Empire would end in the spirit of the famous Latin aphorism: Thus passes the worldly glory.i

The frist part of our story you will find here.

Engraving of Ottoman Empire's military: Eghri Calpaklissi, soldier of the reformation; Choubarà Néféri, soldat of the 1st reform; Nizami Djedid Néféri/Alamy

What to read

Çamuroğlu, Reha. Yeniçerilerin Bektaşiliği ve Vaka-i Şerriyye. Istanbul: 2006.

Cazacu, Matei. Dracula. Leiden: 2017.

İnalcik, Halil. The Ottoman Empire. The Classical Age, 1300-1600. London: 1973.

Gül, Abdulkasim. Yeniçeriliğin Tarihi. Cilt 1-2. Istanbul: 2022.

Kafadar, Cemal. Kim Var İmiş Biz Burada Yoğ İken. Dört Osmanlı Yeniçeri, Tüccar, Derviş ve Hatun. Istanbul: 2009.

Koçu, Reşad Ekrem. Yeniçeriler. Istanbul: 2004.

Mihailović, Konstantin. Memoirs of a Janissary. Ann Arbor: 2010.

Özdemir, Serdar. Osmanlı Devleti'nde Devşirme Sistemi. Istanbul: 2008.

Stavrides, Theoharis. The Sultan of Vezirs. The Life and Times of the Ottoman Grand Vezir Mahmud Pasha Angelovic (1453–1474). Leiden: 2001.

Toroser, Tayfun. Kavanin-i Yeniçeriyan (Yeniçeri Kanunları). Istanbul: 2011.

Uzunçarşılı, İsmail Hakkı. Osmanlı Devleti Teşkilâtından Kapukulu Ocakları. 1. cilt. Ankara: 1988.

Wheatcroft, Andrew. The Enemy at the Gate. Habsburgs, Ottomans, and the Battle for Europe. New York: 2010.