The fates of Kazakh heroes from the Second World War are well-known to the country’s people. There is a square, park or street in every city of Kazakhstan bearing one of these glorious names, a daily reminder to their courage and resilience. And yet, it is worth repeating the stories of these people who were immortalized by their heroic deeds. At least so that new generations do not forget the trials that fell to the share of their great-grandfathers. And great-grandmothers.

It was always somewhat of a surprise to anyone who knew Aliya Moldagulova personally just how serious, focused and demanding she was—top of the class, best markswoman in her year, et cetera. But in all likelihood, Aliya’s life started out very differently. She was once as happy and carefree as other girls her age—she just had to get serious very early in life.

AN UNCHILDLIKE CHILDHOOD

Aliya Moldagulova was born on 15 June 1925* [*In official records, however, Moldagulova’s birthday is recorded as 25 October 1925.] in a village called Bulak in the Khobdinsky district of the Aktobe region. Her father Nurmukhambet’s surname was not Moldagulov, but Sarkulov, and she came from a noble Tabyn family of the Jetisu tribe of the Junior jüz. As a result of his background, Nurmukhambet was severely harassed by the Soviet authorities—he was not allowed to work normally and support his wife and children (Aliya had a younger brother and possibly a sister). In the mid-1930s, he took his wife’s surname and moved to a place where they were not known, but this did not save the family either.

In 1933, Aliya’s mother, Marjan, was shot by a guard as she walked past a collective potato field. This event is usually described as an accidental tragedy, but considering the famine in Kazakhstan that year, perhaps Marjan was not simply passing by a collective farm, and her death was not an accident.

Nurmukhambet buried his wife somewhere in the lower reaches of the Quraily River, where they were then wandering. He was crushed and destroyed, having neither the strength nor the means to deal with his children, and so he left them and disappeared. Aliya and her younger brother wandered various villages for about a year, surviving on the streets of small towns. It appears that her younger brother, Bagdat, died during this time. Aliya, however, was lucky: her maternal uncle, Aubakir Moldagulov, found the girl and took her to his home in Almaty. She was then ten years old and went to school for the first time.

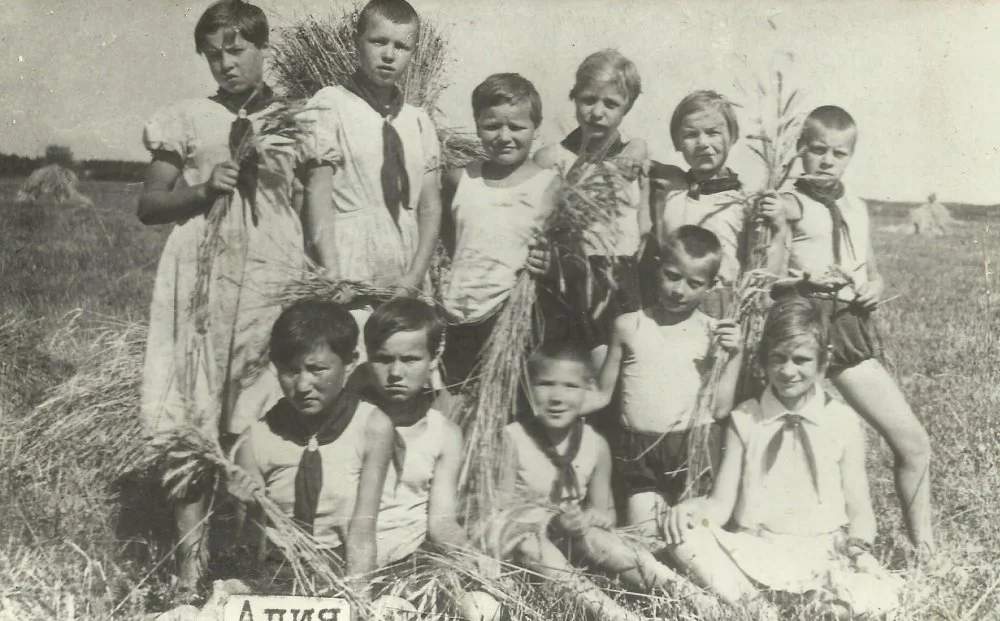

Presumably the picture was taken in an orphanage. Aliyah is at the bottom left/E-history

Yet, stability eluded her. Aubakir Moldagulov soon enrolled in the Military Transport Academy in Moscow and moved to the capital. Seven other family members moved with him, including women, children, and old people. Though times were hard, it was impossible to leave loved ones to their fate, and Aubakir, despite his youth, supported the family. A few years later, the academy moved to Leningrad. He moved, his whole family followed him once again, and that’s how Aliya ended up in the city.

Initially, she went back to school. Her first teacher later recalled: ‘Liya was ... an exceptionally serious, thoughtful, inquisitive girl. She took great care of the class, was the first assistant and did not tolerate slackers. In the sixth and seventh grades, she was at the top of the class.’

A. Moldagulova's memorial plaque on the Vyatka School building/Vitaly Barsov/Wikimedia Commons

A YOUNG GIRL IN LENINGRAD: BOARDING SCHOOL AND THE SIEGE

Life continued to be difficult for Aliya. Nine people lived in one small room: Moldagulov, his wife, his three children, his sister Sapura (Aliya’s aunt), two grandmothers, and Aliya. Aliya had a close relationship with her aunt Sapura, who was almost the same age as her. Because of this, Aliya referred to Sapura not as her aunt, but as her sister.

In 1939, Aubakir sent the fourteen-year-old Aliya to Boarding School No. 46. A few years later, this school was officially reformed into an orphanage, which it had essentially been all along. One can only imagine how Aliya must have felt after her immediate family had been shattered and the other had cast her out.

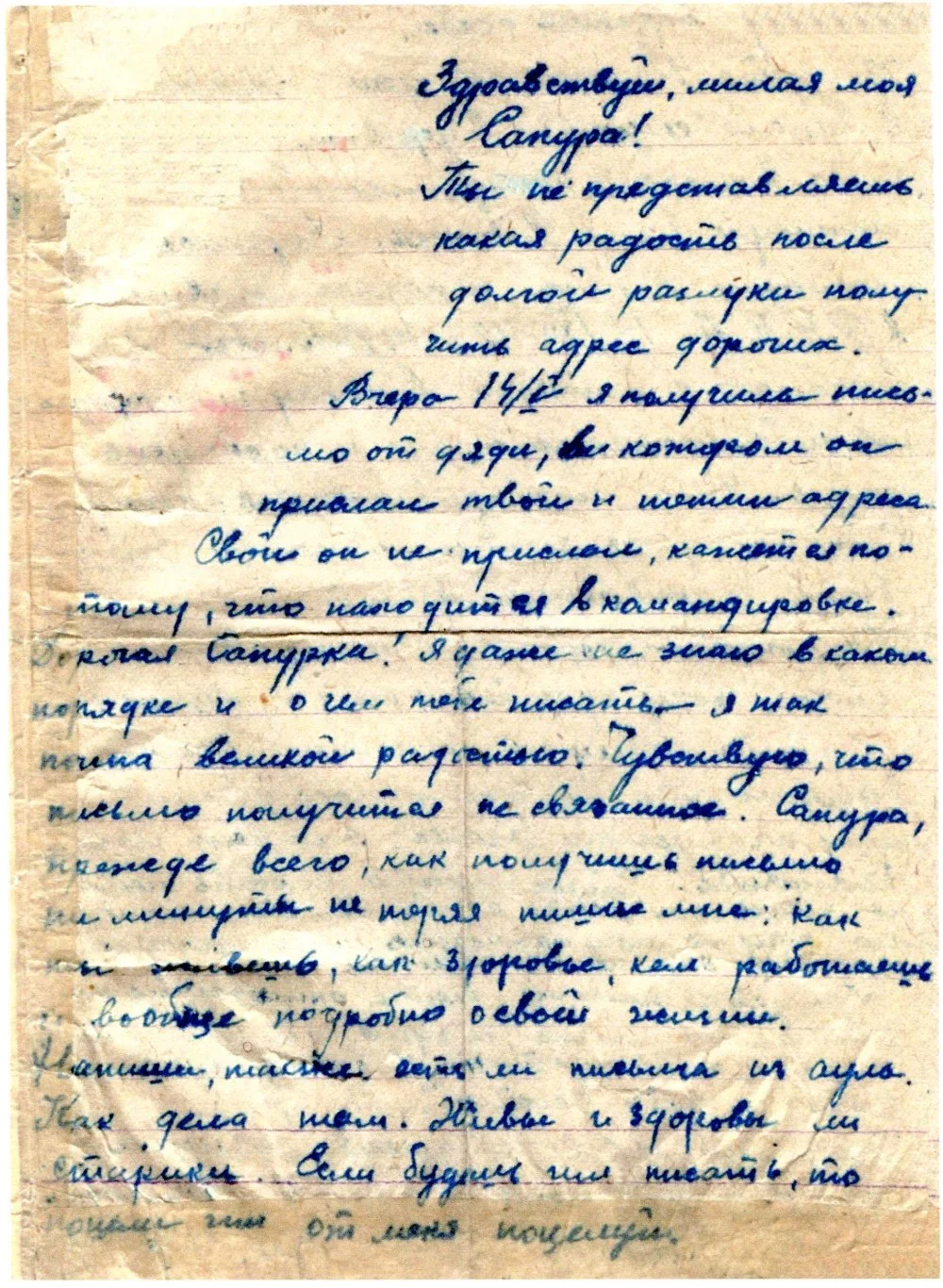

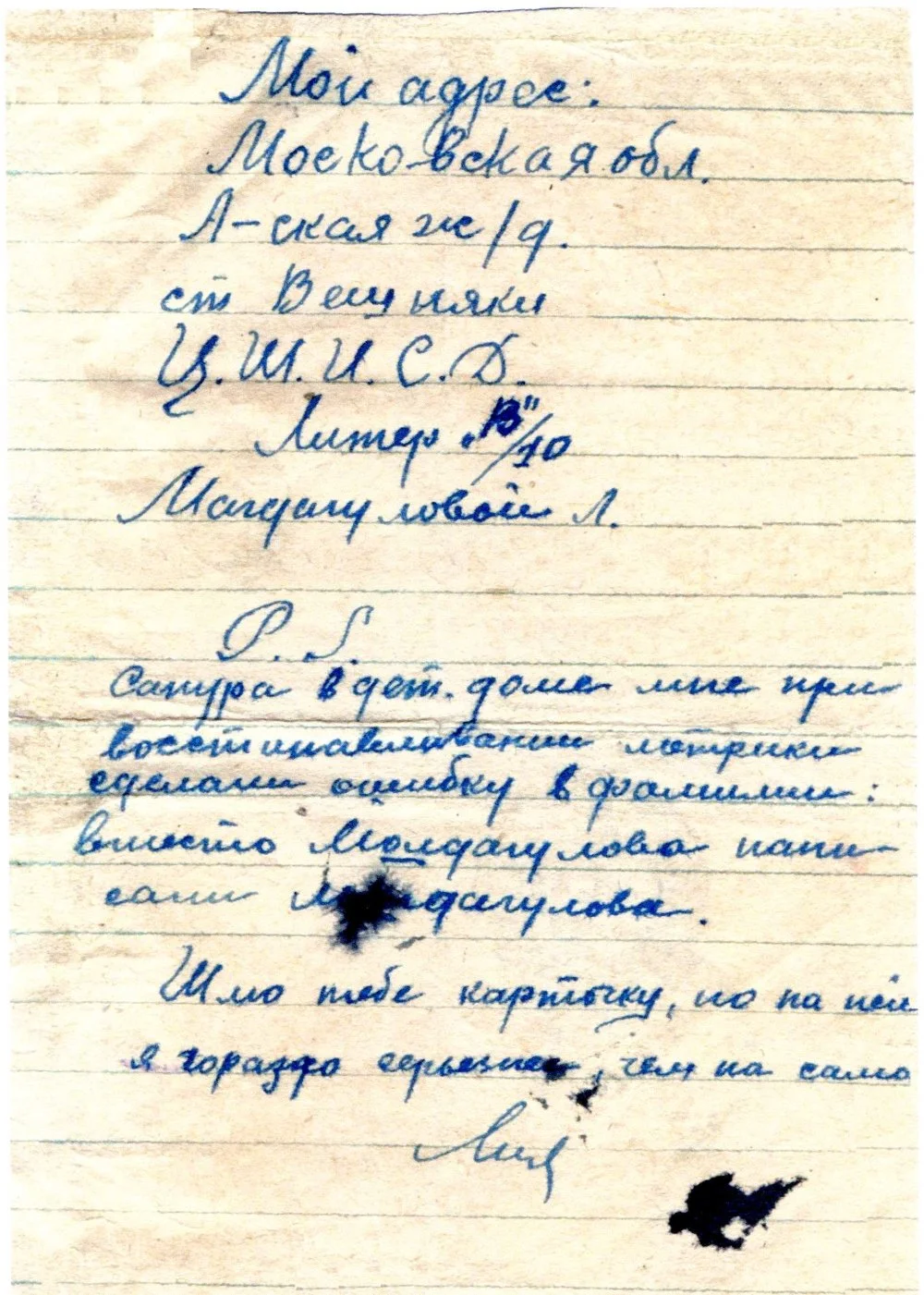

In 1985, a Kazakh film studio made a movie about Aliya’s life called Snipers, in which the main character directly states that her aunt beat her and forced her husband to give the girl to an orphanage. Was this, in fact, true? On the one hand, in her letters to Sapura, Aliya always sent her greetings to all the members of the family, including her aunt. On the other, these letters sometimes show that her aunt was a difficult person and their relationship was strained. For example, in a letter written in July 1943, she says: ‘I’d like to ask you to write a letter from me to my aunt—I want to do it myself, but it is very difficult for me to express the thoughts that she needs. Write to her about my departure, write that I feel well, my mood is good—do not let her be upset. Tell her that I ask her to be affectionate to the little ones, even though she, as a mother, may offend her children, even though she loves them. My uncle, when he came to see me, expressed some displeasure that she was cruel to her little ones.’

One of Aliya's letters/From open access

If the mother was cruel to her own children, the foster daughter probably also received the same cruelty from her. But we have no direct evidence that the aunt beat Aliya.

In the orphanage, Aliya studied well and was an active Young Pioneer, and in 1941, she received a voucher for the Artek Camp. She had already packed her things, but the Second World War broke out, and instead of going to a Pioneer camp, Aliya went with other children from the orphanage to build earthworks.

In November 1941, the sixteen-year-old girl was accepted into the Komsomol (Young Communist League). Along with other orphans and ordinary Leningrad children, she spent nights on duty in the city, extinguishing fire bombs. At that time, Aubakir managed to move his family to Tashkent. This move cut off communication with the family for almost two years, and Aliya was left alone in the besieged city.

Hero of the Soviet Union (posthumously), sniper of the 54th separate rifle Brigade of the 22nd Army of the 2nd Baltic Front Aliya Nurmukhambetovna Moldagulova. USSR. 1943-1944/ТАСС

Aliya barely survived the first, most terrible winter of the siege. Her former Young Pioneer leader recounted how the young girl once went out with a sleigh to fetch water and did not return. They ran after her and found her lying in the street. The doctor who examined her said that she had lost consciousness due to exhaustion. When Aliya woke up and was questioned, it turned out that she had been giving half of her rations to a small and weak girl called Katya. In the end, Katya survived and Aliya nearly died.

THE GIRL WHO WANTED TO FIGHT

In March 1942, the orphanage was evacuated along the ‘Road of Life’ to the village of Vyatskoye in the Yaroslavl region. But Aliya did not stay there long. After graduating from seven-year school (the equivalent of secondary school), she went alone to the unfamiliar town of Rybinsk and enrolled in an aviation school—we know that she dreamed of becoming a pilot to fight the Nazis in the air.

This move is, in fact, one of the most mysterious facts of her short biography. Aliya entered the technical school to specialize in ‘cold metal processing’, which certainly did not include any instruction on flying. After three months, disappointed with her chosen profession, she submitted documents to the military recruitment office with a request to register as a volunteer in the Red Army.

Some biographers explain her unsuccessful choice of specialty by the fact that Aliya’s Russian was still limited and she did not understand the documents. However, this is certainly not the case. After all, Aliya was the head girl in a Leningrad school; it is quite unlikely that she would have been chosen if she did not understand Russian fluently. Moreover, her school report card has been preserved, demonstrating only ‘good’ and ‘excellent’ grades in all subjects.

«I can’t write everything I want in Kazakh, and I don’t think she will understand everything if I write in Russian»

niper school. Aliya Moldagulova is the third from the left in the first row

Also, in May 1943, her uncle sent her a new address for the family, and she began writing to Sapura again in good, fluent Russian. In her first letter, she wrote: ‘I would like to ask you to forgive me for not writing in my native language. I think you have guessed why I am writing in Russian: it is easier for me to explain myself. Now I have to write to my aunt—I don’t know how to do it. I can’t write everything I want in Kazakh, and I don’t think she will understand everything if I write in Russian.’

However, this letter is also puzzling in its own way. What is it that could be written in Russian and not in Kazakh? One explanation could be that Aliya did not really want to communicate with her aunt and used this as an excuse. Later, she would ask Sapura to send her aunt greetings and apologize for not writing.

At the draft office, the young girl faced disappointment once again. She was only seventeen years old, and you had to be eighteen to be drafted to the front. However, Aliya did not give up: she talked to the draft officers about the siege, about her beloved city surrounded by enemies, about the suffering of its inhabitants, and about her desire to help them. The military commissars found a compromise: the girl was sent near Moscow, where in the village of Veshnyaki the Central Women’s Sharpshooter Training School was being established. After this training she would turn eighteen and could go to the front. This option satisfied everyone.

Hero of the Soviet Union Aliya Nurmukhambetovna Moldagulova in the 1940s.Kazakhstanskaya Pravda newspaper dated June 25, 1944/Wikimedia Commons

There, at the Rybinsk draft office, Aliya met Nadya Matveyeva, who had also come there to volunteer, and was sent to the sniper school. Later, at the front, the girls became a sharpshooter pair and best friends. After Aliya’s death, Nadya was often interviewed, and in many ways our image of Aliya at the front was shaped by her memories.

Nadya also talked about their studies. She said that the conditions were difficult; they slept in a greenhouse on three-tiered bunks, and it was very cold, with no place to dry clothes and shoes. The former school commissar Yekaterina Nikiforova noted: ‘The siege left its mark on Aliya’s immature body. She was often plagued by boils. Small in stature, fragile, she bravely overcame the pain and tried to keep up with her classmates as everyone ran and trained, surprising us all with her endurance and strength of character.’ Fellow students told reporters about Aliya running off to the forest after lights out to learn to climb trees (there were few forests where she grew up, and Aliya thought she needed extra lessons as could not climb trees), or marching with her feet scuffed in soldier’s boots.

There is no mention of such things in Aliya’s letters from sharpshooter school. In one letter she wrote to Sapura and said, ‘Today I went to the forest to pick flowers. I picked a bunch. The forest is close to me, and there are fields all around, lots of flowers, and they are beautiful. So that I do not enjoy them alone, I am sending you a carnation, a forget-me-not, and strawberries.’

On the set of the film directed by Bolotbek Shamshiev «Snipers», dedicated to the Hero of the Soviet Union, Alia Moldagulova. Kazakhfilm Film Studio, 1985/Galina Kmit/RIA

Interestingly, she usually signed her letters, ‘Kisses, Liya.’ Her Russian friends had begun to call her ‘Liya’ when she was probably still at school in Leningrad. She liked the name and later used it to introduce herself.

Fellow students recalled that Liya was very enthusiastic about most things. She read poems at amateur art evenings (the recruits engaged in rifle training for fifteen hours a day, but they still found time for amateur activities) and held lectures on political developments and events.

In July 1943, she graduated from the sharpshooter school. Since Aliya was still very weak after the siege and her grades were excellent, she was offered an instructor’s position at the school for a few months. She flatly refused and left with her fellow students for the northwestern front.

Once they arrived, they were assigned to the 54th Separate Rifle Brigade. The first thing their battalion commander said was that they were not to go to the front but to do work in the rear. Aliya and Nadya were not satisfied with this order and solved the problem in a purely original way: both sharpshooters cried in the commander’s dugout and sobbed until the commander gave up and allowed them to do their work.

Aliya's Letter/E-history

ALIYA AT THE FRONT: MYTHS AND REALITY

Following Aliya’s death and posthumous recognition as a hero, the Red Army’s political department took charge of writing her biography. Various correspondents went to the regiment in which she fought and recorded her comrades and commanders’ memories of her. After the war, this work was continued first by Soviet journalists and then by Russian and Kazakh enthusiasts. As a result, we now have many stories about Aliya that sometimes contradict each other.

For example, many sources mention that Aliya fought with a personal rifle embossed with the words ‘From the Central Committee of the Komsomol for excellent marksmanship’. It is usually believed that she received it at sharpshooter training for doing well in her studies (at least according to the Russian-language Wikipedia article!). It was only when Asylzhan Murzabulatova, a guide at the West Kazakhstan Regional Museum of Local History, turned to the archives of the marksmanship school that it was discovered that Moldagulova was not listed among the distinguished students, and the school did not give her a rifle from the Central Committee of the Komsomol. This would mean that she received it at the front, not for her studies but for her valor in combat.1

From the filming of the movie «Snipers». From the personal archive of the photographer and artist Sirotin P.A. 1985. Tape/CSA CPAD

After Aliya and Nadya tearfully won the right to fight at the front, they became apprentices to Bandurov, the best marksman in the brigade, and he soon sent the girls on their first mission. This is how Nadya Matveyeva describes the mission: ‘I remember our first hunt. We started the hunt from the shelter. We watched all day, but the Germans did not show up. That day, Shura Uzhegova opened the score. Liya was very upset because she didn’t see a single Kraut and envied her friend. But the next day, she opened her score too, and you should have seen how happy she was. Liya had hot Kazakh blood. And this noble blood was often the reason why she sometimes lacked patience. We held the defense on the Lovat River. We were on one bank, the Germans on the other. The distance was about 150 meters. We had to look out a lot and it was tiring. So Liya would look over the barrier and yell: “Kraut, show yourself!” and whistle. We always said that if she died here, she’d die a stupid death. And she just laughed back.’

In fact, there was nothing funny about it, and Bandurov scolded his apprentice for this prank. Young sharpshooters often faced fatal consequences for such daring. And Aliya, in particular, had a history of incidents like this, and the case on the Lovat was not the only one. On another occasion, she killed two German observers who were pointing a German mortar battery at the Soviet trenches, and the third shot broke their stereo tube. That third shot was completely unnecessary, but Aliya wanted to show off her marksmanship and gave her position away, after which they immediately opened mortar fire. She was lucky that she was stationed under a destroyed German tank and its armor saved her. Bandurov gave her a hard time for this incident as well.

From the filming of the movie «Snipers». From the personal archive of the photographer and artist Sirotin P.A. 1985. Tape/CSA CPAD

Another time, an enemy marksman could have punished her for her misplaced courage. Aliya took a shot and looked out to see if it was successful. The German sniper fired back immediately, and the girl was lucky that the bullet only grazed her helmet, leaving a dent.

Despite her carefree attitude toward danger, Aliya turned out to be a very talented sharpshooter. She arrived at the front in August and by October, she had killed thirty-two Nazis. She quickly became a respected fighter in the brigade and took her fellow Kazakhs under her wing. In her letters to Sapura, she referred to them as ‘my nomads’.

A number of trench legends—of varying degrees of plausibility—also emerged about Aliya, which fellow soldiers related to journalists. The first legend tells of how a group of five girls led by Sergeant Moldagulova was sneaking around neutral ground to take up positions closer to the enemy trenches when they came across a group of Germans doing exactly the same things. The girls reacted first to the unexpected encounter, and Aliya and two of her friends fired—three Germans fell dead and the girls took the remaining two prisoners. The whole Wild West-style shootout sounds straight out of a movie, of course, but it could theoretically have happened.

‘Dear Sapura, I will imagine living with you there, in my native Kazakhstan. Oh, how I would like to see you, to visit my native aul! But it’s all right. The hour will come when we will celebrate our meeting, our return to our homeland, and our victory. All together.’

The second story, however, is less plausible. According to it, Aliya disguised herself as a peasant, pretending to be a local, and went behind enemy lines. She entered a hut at the edge of a German-occupied village, and saw two German officers sitting at a table. One of them grabbed a gun, but Aliya fired first and killed him. She captured the second German, and he provided valuable information to the Soviet command.

The idea of sending a sharpshooter on such a reconnaissance mission seems very strange and unlikely in itself, but it pales in comparison to the idea of sending a Kazakh woman posing as a local behind enemy lines in the Novgorod region. Most likely, these are just soldiers’ tales or Soviet journalists’ fantasies. Or perhaps they were both. After the war, front-line soldiers first told the journalists all sorts of fabrications and then the journalists added to them. This phenomenon, interestingly, poses a big problem in the study of the Great Patriotic War. Quite often, former soldiers clearly mocked journalists while giving interviews, telling them absolutely unbelievable stories with a straight face. Those who had not been in the war believed everything and then retold these stories to their readers, adding their own details. Many untruths were written in them. For example, the enemy’s losses were almost always exaggerated, but no one would write fictitious stories there just because it is very amusing to pull the wool over the eyes of an ignorant person. After all, a document is a matter of responsibility, and its author could be dismissed or even court-martialed. And now, when all the participants are dead, it is hard to identify the truth from the fiction in these recorded memories, and this is why we must study these archival documents. It must be remembered that many untruths were written in them. For example, the enemy’s losses were almost always exaggerated, but no one should write fictitious stories just because it is very amusing to pull the wool over the eyes of someone who doesn’t know better. After all, a document is a matter of responsibility, and its author could be dismissed or even court-martialed.

From the filming of the movie «Snipers». From the personal archive of the photographer and artist Sirotin P.A. 1985. Tape/CSA CPAD

Throughout the summer and fall of 1943, the 54th Independent Rifle Brigade was stationed near the town of Kholm, where they had surrounded a German group. Their mission was to prevent the Germans from breaking out of the Kholm cauldron, and they did not try to break out in their area. It was a war of positions, and life was more or less settled on well-fortified lines. And this is why Aliya grew in prominence as a sharpshooter so quickly—there were no big battles, the enemies worked against each other with marksmen, reconnaissance teams, and mortars. However, this quiet life (by frontline standards) soon came to an end.

In November 1943, their rifle brigade was transferred from near Kholm in the Novgorod region to the Novosokolniki area of the Kalinin region. They were to take part in a great battle—the lifting of the siege of Leningrad. The battle involved several fronts, a dozen armies, about a hundred divisions. All of them had to advance in different directions, not only to reach the besieged city, but also to encircle the German troops blocking it. However, the task of their front was more modest: to bind the enemy’s 16th Army so that it could not come to the aid of the German troops near Leningrad.

The poster of the movie Snipers/From open sources

On 13 December, Aliya wrote another letter to Sapura: ‘Now we are at the front. I am writing this letter in a deep trench; there are many trees around. We are facing the Germans. I have a helmet on my head, a grenade behind my belt, and a rifle in my hands. I do not feel sorry for the Krauts, but at first I was a little worried.’ Later, she recounts how the commander gave her a commendation in front of the line for killing fourteen Nazis in three days: ‘... then he kissed me in front of the people like a son, and I blushed with shame.’ This moment is worth remembering because it would cause much confusion later.

The offensive began on 12 January, and it went badly from the start. The Soviet troops had been conducting local operations in the Novosokolniki area throughout the fall of 1943 and had only recently reached the lines from which the January offensive was launched. Thus, they were advancing on unfamiliar terrain against defenses whose system was almost unknown to them. As it turned out later, the Germans did not have a solid line of defense here. They held separate strongholds and carefully camouflaged pillboxes, the location of which could not be determined by intelligence. The troops thought that they would break through the solid defense, and the artillery preparation was carried out on the entire width of the front, that is, most of the shells were fired on an empty area. As a result, the enemy fire points were not suppressed, and the entire 22nd Army and the entire 2nd Baltic Front got stuck in the snow in front of them. The 54th Independent Rifle Brigade was the only one to achieve any notable success during the first two days: it broke through the German defenses north of Novosokolniki and reached the railroad at Nasva Station, from which it was able to drive the Germans away. But soon it came under very heavy fire and went to the ground too.

From the filming of the movie «Snipers». From the personal archive of the photographer and artist Sirotin P.A. 1985. Tape/CSA CPAD

At the same time, the main offensive at Leningrad was developing quite successfully, and it was very important to continue to maintain a threat for the Germans at Novosokolniki and prevent them from moving reinforcements there. It turned out that only the 54th Brigade could do this, and the next day they were ordered to continue the offensive and cut the railroad.

On 13 January, they attacked and repulsed the German counterattack all day. They continued to advance, though very slowly, paying for every meter gained with blood. On the morning of 14 January, they attacked again and took the village of Kazachikha. And that was where Aliya Moldagulova died.

THE DEATH OF ALIYA MOLDAGULOVA

The circumstances of Aliya’s heroic deed and subsequent death are rather vague and contradictory. According to some sources, she was the sharpshooter covering the offensive of the brigade’s reconnaissance platoon. According to others, she was reassigned from being a sharpshooter to a machine gunner just before the offensive began. Judging by all the descriptions of the circumstances of her death, the second is much more likely, which seems like a very strange decision. A talented sharpshooter is a unique specialist, and they are not usually thrown into frontal attacks against German machine guns. Besides, a fragile eighteen-year-old girl who had only recently survived a siege was obviously not well suited for assault work. But Aliya advanced in infantry columns, and she earned her gold star as an assault soldier and not as a sharpshooter.

A shot from the film directed by Bolotbek Shamshiev «Snipers», dedicated to the Hero of the Soviet Union, Alia Moldagulova. Kazakhfilm Film Studio, 1985. Aliya Moldagulova - actress Aiturgan Temirova/Galina Kmit/RIA

Aliya’s feat was to rally the infantry under fire. How many times she did this and how exactly it happened are not very clear from the stories that have survived. For example, Nadya Matveyeva alone told two slightly different stories: ‘In the heated battle for the village of Kazachikha, the commander was wounded. Aliya rose to her full height and shouted, “Forward, for the Motherland!”, dragging the platoon of the remaining fighters behind her. We broke into the enemy’s trenches …’ The other story Matveyeva told about these events was something like this: ‘Then Aliya stood up ... The whole company followed her and broke into the enemy trenches. A mine exploded, and Liya was wounded in the arm, while I impulsively rushed forward ... Then I learned from the soldiers behind us that Liya, despite her wound, did not drop her machine gun and shot an enemy officer. But he managed to shoot back and wound Liya a second time. But she had the last shot. She was carried off the battlefield by the commander of the reconnaissance team, Polyakov, and three other soldiers whose names I do not remember.’

From the filming of the movie "Snipers". From the personal archive of the photographer and artist Sirotin P.A. 1985. Tape/CSA CPAD

There are also different accounts of what she shouted as she led the men into battle. Some recall that it was the words ‘Brother soldiers, follow me!’ in Kazakh because there were Kazakh soldiers around Aliya, her ‘nomads’, and she addressed them in their native language. The citation for Corporal Moldagulova, however, states that she shouted what Soviet heroes were supposed to shout during an attack: ‘For the Motherland! For Stalin!’ In fact, this award sheet contains many details that are not in the stories of people close to Aliya who fought with her that day. In this document, Aliya not only rallies and leads the soldiers but also kills Germans by the dozens, takes village after village, destroys German machine guns and mortars, and takes prisoners.

From the filming of the movie «Snipers». From the personal archive of the photographer and artist Sirotin P.A. 1985. Tape/CSA CPAD

If you read articles about this feat in the newspapers of the war, they show that from 12 to 14 January, Aliya Moldagulova rallied the infantry in the attack six times.

It is, as one can imagine, an impossible task to put all this into a coherent story. The most dramatic story of Aliya’s death, however, was told by another friend. Zina (Zinaida) Popova was also a sharpshooter, who, after the war, married the brigade scout Polyakov and took his surname, and this is her version recorded after the war: ‘Liya was shooting at the advancing enemy from the attic of a house. A shell exploded nearby, and she was badly wounded. The scouts carried her to the village barn, where the wounded were. The fighting continued. The barn caught fire because of the mines and shells, and not all of the wounded could be carried out. Liya also died. I was also wounded in this battle and was evacuated to the hospital.’

It is significant that Galymjan Baiderbesov, a respected authority on Aliya Moldagulova’s life, has recently started to support this, the most terrible, version of Aliya’s death in his recent books. But the films, articles, and books usually tell the most heroic version of the shootout with a German officer, in which Aliya won her last victory. It’s understandable—the image of a wounded girl being burned alive is perhaps a bit too much for film.

There is still a mystery that we will try to solve. All sources say that Aliya Moldagulova killed seventy-eight German soldiers. Where did this number come from when all her sharpshooter friends say that she killed thirty-two Nazis by October 1943?

Most likely, this number was taken from the award sheet. If you count all the Germans she killed according to this document (10+12+23+last officer) and add them to her score of 32, you get 78. And then, by the way, it turns out that Aliya killed more Germans as an assault rifleman than as a sharpshooter.

But let us also take a moment to remember her letter of 13 December, in which the commander kissed her ‘like a son’ for killing fourteen Nazis in three days. These are not included in her account (which is only for October), and they are not included in the award list (which only describes the last two days of her life). That’s why many historians say that Moldagulova’s account actually includes almost a hundred enemies killed.

Statue of Aliya Moldagulova and Manshuk Mametova in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Taylor Weidman/Bloomberg via Getty Images

One could get the impression that Aliya died for Leningrad, a city she loved, where she seemed to have found a home. But it is not quite accurate to frame the question in this way considering the Soviet past. People of different nationalities were raised in Leningrad from childhood to think that they lived in one big, hospitable house, although we now realize that it was merely propaganda.

It is clear from Aliya’s letters that Kazakhstan remained her home. In her letters to Sapura, she constantly inquired about news from her native village, about the lives of her relatives (whom, frankly, she had no reason to love, but she loved them anyway), and she had dreams of returning to Kazakhstan after the war. Yes, Aliya saw her future not in Leningrad, but in her homeland. In a letter, she writes unequivocally: ‘Dear Sapura, I will imagine living with you there, in my native Kazakhstan. Oh, how I would like to see you, to visit my native aul! But it’s all right. The hour will come when we will celebrate our meeting, our return to our homeland, and our victory. All together.’