This isn't a mere ranking, nor is it in any random order. No, what we've crafted here is more like a treasure trove of cinematic gems handpicked just for you.

This is the first part of our anthology of the best Kazakh films. The second part can be read here.

Our attention is laser-focused on narrative cinema, leaving the realm of documentaries, animations, and TV series for future editions. So, buckle up for a curated collection that's meant to be cherished.

"My Sister Lucy" (1985)

Directed by Yermek Shinarbayev

A cosmonaut with the resonant voice of Innokenty Smoktunovsky orbits Earth, reminiscing about post-war years in a Kazakh town. His memories traverse back to his seven-year-old self, his mother Aygul (Khamam Adambaev), a widow named Klava (Olga Ostroumova), Klava's twelve-year-old daughter Lusya (Larisa Velikotskaya), their dog Pirate, and the latent bitterness of childhood.

Yermek Shinarbayev's debut film, scripted by Anatoly Kim, heralded the precursor of the new Kazakh wave, though not formally tethered to it. Nevertheless, it glimpses some of its techniques and contours. For instance, the operational television set within the frame emerges as a recurring motif in the poetics of the new wave. Kazakhs sheltering Russians during evacuations is another recurring theme in local cinema, as in "Return of the Son" by Sharip Baysembeev (1977), which also narrates a Kazakh woman raising a Russian boy during the war. Another prevalent topic is an elderly figure as a mystical mentor for a young protagonist, akin to Klein in Serik Aprymov's "Three Brothers" and Suntselov in "The Balcony." Here, Nikolai Grinko, a Lithuanian newcomer who lost his family in the war, embodies that role, narrating an allegory of the Old Testament's Job to the boy: "Job was right, I was right too, but God returned nothing to me."

Teapots, bazaars, ice-chilled water, gramophones, sewing machines, war veteran amputees, colossal tomatoes on the beach, suicide attempts, eagerly awaited reunions on railway tracks... "The world is crumbling like an immense sandy precipice," Smoktunovsky utters. Indeed, God returned nothing.

"My Sister Lucy" (1985) Directed by Yermek Shinarbayev

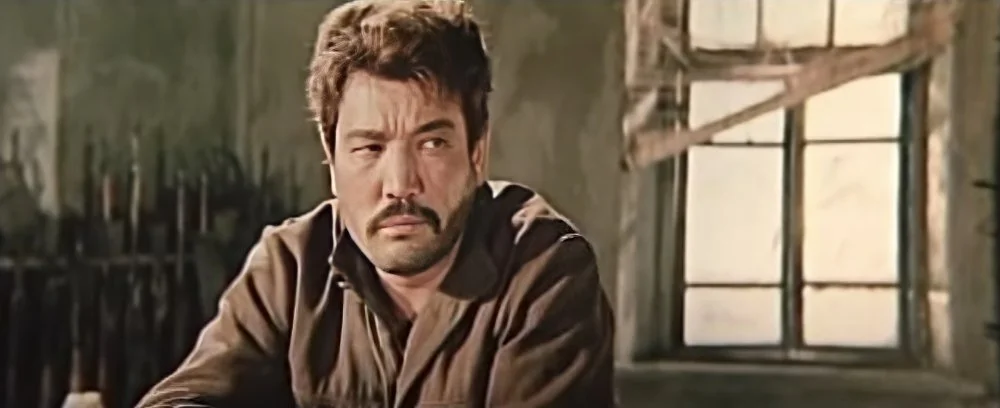

"Personal Growth Training"

(2018) Directed by Farkhat Sharipov

The unassuming and sober clerk Kanat (played by Duliga Akmolda) lives with his mother, who is rapidly succumbing to Alzheimer's. He toils at a struggling bank, handling analytical projects, donning a shabby suit for work, timidly masturbating under the sheets, and attending personnel management training. A turning point occurs when his former Astana classmate, now a prominent financier named Daniyar (Erzhan Tusupov), relocates to Almaty. Daniyar dreams of having his portrait painted by an artist. One evening, he drags Kanat to a sauna with women, after which one of them vanishes without a trace. Daniyar explains that prostitutes often vanish. And seemingly nothing has changed.

One of the greatest films in the history of modern Kazakh cinema begins with the mournful maternal wailing of a deceased girl’s mother, and everything that follows can be seen as an attempt to quiet and rearrange it, aided by the splendid acting duo of Duliga Akmolda and Erzhan Tusupov. In this film, Tusupov holds his ground against Javier Bardem (even resembling him physically ), creating an incredibly authentic character - a former wrestler, a lover of singing "There's Just the Present Moment*" in karaoke, and an adept of savage intimacy ("I ravage her, and her eyes roll back in their sockets ").

There are no excruciatingly brutal scenes like in "Happiness" or "The Rejected Ones." This film isn't about banality; rather, it's about a kind of cozy dissolution of evil. Evil permeates everything – it lingers in the word "brother," in the friendly rounds of vodka drunken from plastic cups, in girls' dreams of owning a Lexus, in driving on Rosebakiev Street during a flurry of wet snow. The little man eventually transforms into a conformist, nibbling at a fragment of the malevolent pie. The film is quite aptly named "Personal Growth Training."

"Training of personal growth" (2018) Directed by Farhat Sharipov

"Woman Between Two Brothers" ( Razluchnitsa) (1991)

Directed by Amir Karakulov

Elder brother Rustem (Rustem Turkmenbaev) brings home his lover Dalmira (Dana Kairbekova). His younger brother Adil (Adil Turkmenbaev) falls for her. The trio convenes for tea in an apartment reminiscent of a prison cell, and it culminates with the muffled wolf-like howl of the girlfriend from under a stifling pillow as soft snow descends beyond the window, restoring a silent brotherly equilibrium.

Four walls, three individuals, two siblings, one outcome, zero emotions – such constitutes the elegiac arithmetic of Amir Karakulov's debut, a loose adaptation of Borges' "The Deceiver." Among all films depicting love triangles, this stands as the most distinctly delineated and austere. Minimalism is pursued to its unadorned extremity, where all coins are strictly two kopecks each, onions are the sole foodstuff in view, and the only temporal cues are a The Beatles poster on the wall and the "Don't Worry, Be Happy" song accompanying a lethargic street skirmish. It's a sort of godless Bible wherein the ideal conversation transpires like this::

- Why?

- Just because.

"Woman Between Two Brothers" marked the first Kazakh film featured at the Venice Film Festival, fitting seamlessly into the global cinematic tapestry. When the brothers engage in a matchbox game, it's a direct homage to Truffaut's "Jules and Jim," while the breath-holding contest underwater in the pool as a wager is unmistakably inspired by Luc Besson's "The Big Blue." The pool, incidentally, is a pivotal setting for the new Kazakh wave, appearing in "The Needle" and "In Love with a Fish." Nonetheless, in "The Homewrecker," there are not only borrowed elements but also foreshadowings: for instance, the scene where the characters get stranded on a Ferris wheel, depicted here, is described by Haruki Murakami in "Norwegian Wood" eight years later.

"Razluchnitsa" (1991) Directed by Amir Karakulov

"Sweetie, You Won't Believe It!" (2020)

In the year 2020, three friends with varying degrees of simplemindedness -Danier Alshinov, Erlan Primbetov, and Azamat Marklenov—embark on an unexpected adventure. Their destination? A fishing trip. But this isn't just any ordinary fishing trip. One of them has left behind his peculiarly suspicious and heavily pregnant wife. As they set off on this curious escapade in a rather unconventional vehicle- it’s loaded with inflatable sex dolls. Believe it or not, this is going to be a hilarious trip!

There is a poetic concept that can be explained as ecstasy for no apparent reason, and in this film, it finds an unexpected cinematic home. "Sweetie, You Won't Believe It!" isn't merely dark humor; it's a journey into the realm of dark hilarity.

Picture an indie film with a splash of slasher, masterfully brought to life by the independent film company Artdealersmovie. An outrageous trash circus with pools of blood and urine, where a wild blend of ingredients expertly blend. On one hand, it masterfully navigates the dark stylings of South Korean horror and absurd thrillers. On the other, hints of Emir Kusturica's distinctive touch, reminiscent of his "Black Cat, White Cat" era, are unmistakable, especially in the scenes of one character's constant fainting spells. Yet, it doesn't stop there. Amid the chaos, fragments of real-life situations—ranging from psychotherapy sessions to the TV series "Brigada"—are tossed into the mix, converging into a concoction of pure idiocy.

Notably, Danier Alshinov's comedic talent shines through in this film, a delightful surprise for those familiar with his roles in "Goliath" and "Black, Black Man." This ability to pivot is characteristic of local filmmakers. For instance, if you were to watch the drama "Taraz" followed by the comedy "Kelinka Sabina," it would be hard to fathom that both were crafted by the same director, given their stark differences.

Had an alternate tagline been needed for this film, a fitting option might have been the catchy phrase found within: "Let Me Show You How Fish are Caught at the Local Government Office."

"Sweetie, you won't believe it!" (2020)

"Air Kiss" (1991)

Directed by Abay Karpykov

Meet Nastya, a seventeen-year-old nurse (Estonian actress Katariina Korma) of celestial beauty, who falls in love with a racer who was admitted to the hospital after a crash. However, her romantic predicament is far from simple. She has a fiancé, the chief doctor who also happens to be an abuser (Oleg Rudjuk), a romantically infatuated limping admirer, Kolya, from the hospital greenhouse (Konstantin Rodnin), and several other lustful contenders from the ranks (Valentin Nikulin).

This is probably the most erotic film in the history of Kazakh cinema. The first phrase that reaches the screen is as follows: "Sex hormones regulate the development and functions of sexual organs," and the initial title itself against an ultramarine background, "Presented by Studio XXL," looks impeccably sinful.

While "Little Fish in Love" perfectly captured the mood of Soviet-era restructuring cinema, "Air Kiss" fully embraces the enchanting trash mirages and easily accessible pop culture of the early 1990s. The heroine strolls around in a tiny nymphomaniac's robe with a generous décolleté zone and concealed panties in her pocket. She wears red boots and a white hat and quotes Shakespeare's Sonnet 116 about love's enduring nature while also discreetly directing a loaded gun between her legs. When she indulges in a box of chocolates in a close-up, the chocolate on her lips looks like blood. (Incidentally, "Little Fish in Love" by Karpikov also featured 300 grams of sweets). Abay Karpikov seamlessly weaves these nearly role-playing games into the fabric of lyrical storytelling. Ultimately, in his later film "Fara," even Christina Orbakaite had a role.

Like any film whose narrative unfolds from a pier to a beach, "Airborne Kiss" delights in its fleeting fatalism, captured in the magical face of Katariina Korma, who hasn't graced the screen quite the same way since.

This is probably the most erotic film in the history of Kazakh cinema. The opening phrase is as follows: "Sex hormones regulate the development and functions of sexual organs," that and the initial title against an ultramarine background, "Presented by Studio XXL," looks impeccably sinful.

While "Little Fish in Love" perfectly captured the mood of Soviet-era restructuring cinema, "Airborne Kiss" fully embraces the enchanting trash mirages and easily accessible pop culture of the early 1990s. The heroine strolls around in a tiny nymphomaniac's robe with a generous décolleté zone and concealed panties in her pocket. She wears red boots and a white hat and quotes Shakespeare's Sonnet 116 about love's enduring nature while also discreetly directing a loaded gun between her legs. When she closely indulges in a box of chocolates, the chocolate on her lips appears like blood (incidentally, "Little Fish in Love" by Karpikov also featured 300 grams of sweets). Abay Karpikov seamlessly weaves these virtual role-playing games into the fabric of lyrical storytelling. Ultimately, in his later film "Fara," even Christina Orbakaite played a role.

Like any film whose narrative unfolds from a pier to a beach, "Air Kiss" delights in its fleeting fatalism, captured in the magical face of Katariina Korma, who hasn't graced the screen in quite the same way since.

"Air Kiss" (1991) Directed by Abai Karpykov

"Angel Wearing Tubeteika" (1968)

Directed by Shaken Aimanov

In 1968, a nurturing mother, ever watchful and caring, sets out on a mission to find a suitable bride for her mature yet unmarried son, Tylak. Tylak, a geography teacher sporting a traditional tubeteika hat, dabbling in kettlebell lifting, and actually thriving in the bachelor format. finds himself entangled in his mother's matchmaking efforts. During the candidate selection process, it becomes evident that the mother's personal life has had and continues to have a rather tumultuous nature, and the film culminates in a double wedding in the end.

This skillfully crafted musical romantic comedy (the well-known Soviet restaurant number "Where are you going, Odysseus?" originates from this film) with its twists and operatic arias carries a hint of the spirit found in Italian erotic comedies from the 60s. However, it's important to note that the film abstains from explicit erotica, aside from the dances in swimsuits. In its place, the film presents a vibrant ode to the Alma-Ata of that day, showcasing its newly built hotel, fountains, beer stalls, alluring waitresses in low-cut tops, information bureaus across from the GATOB building, and football fields that seem to stretch to infinity. The film boldly asserts, "Why Switzerland? This is Kazakhstan. The beauty lies in our own republic." The choice of a geographer as the protagonist is not coincidental.

A noteworthy connection to Gaidai's aesthetics is worth discussing. "Angel" shares undeniable links with "The Diamond Arm," as evidenced by the recognizable music by Zatsepin in the opening credits, dramatic turns, and setups (including a swimsuit fashion show and a scene of unsuccessful seduction reminiscent of the iconic scene with Nikulin and Svetlichnaya at the "Atlantic" hotel). Most intriguingly, both Anatoly Papanov in "The Arm" and Yuri Sarantsev in "Angel" hum the same song, "I Met You," for reasons that remain elusive.

Determining who inspired who is challenging in this scenario. "The Arm" was shot from April to November 1968, while "Angel" had already been released that year.

"Angel in a Skullcap" (1968) Directed by Shaken Aimanov

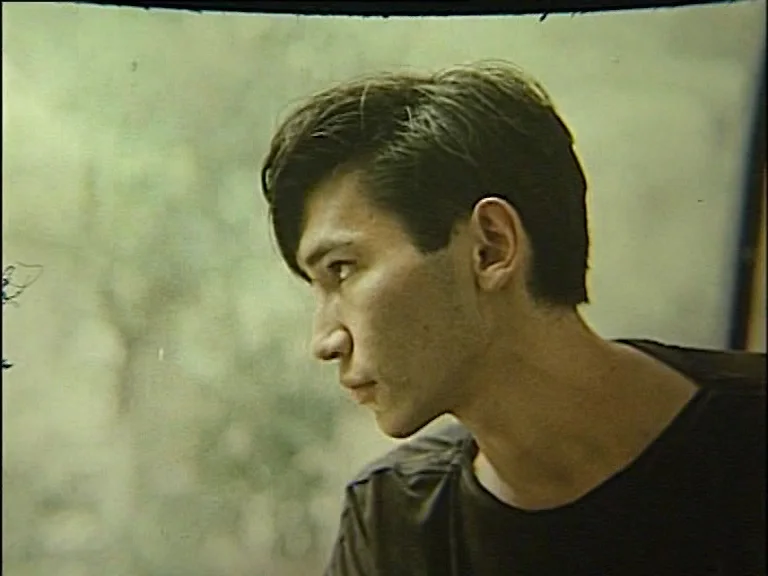

"Little Fish in Love" (1989)

Director: Abay Karpykov

In 1989, Abay Karpykov directed "Little Fish in Love," taking us into the lively life of Zhaken, a spirited rascal portrayed by Bopesh Zhandaev. Wearing an open gray coat, Zhaken sells a cow and a transistor radio—to keep the cow company —before heading from his village to Almaty. His destination? His older brother, Daos (played by Abay Karpykov), whose name alone sparks curiosity. As Zhaken hitchhikes, he playfully waves a pistol—whether in jest or earnestness. In the halted "Volga," we come across Fantik (Satay Dikambaev), a minister with a gangster persona, accompanied by his striking wife Nadiya (Galina Shetanova). A dispute emerges about Nadiya's once-prominent childhood ears, marking the start of a clash between an adventurer and a swindler. This spirited rivalry intensifies, leading to an unexpectedly tender and unpredictable resolution.

The cinematic maxim often attributed to Godard—that a film requires a girl and a gun—finds vibrant life in Abay Karpykov's "Fish in Love." Here, the girl is an exotic element, and the gun becomes a playful prop. This film artfully navigates the balance between an illusory realm of play—where Zhaken's criminal escapades, whether stealing a neighbor's car or robbing a wealthy man in white, evolve into comical adventures—and the detached reality exemplified by a knockout in a nighttime pub. However, this duality transcends the typical village-versus-city dynamic, capturing Karpykov's notion of the predetermined nature of freedom.

This film seamlessly fits into the global context through its use of quotes and occasional predictions. In "Fish in Love," the music of The Platters and the song "Sixteen Tons" make appearances. This incorporation of American pop classics subtly foreshadows the style of another Eastern classic, Wong Kar-Wai, and the enigmatic beauty Nadiya, with her nocturnal strolls along Perov Street, evokes memories of "Chungking Express."

Much of the film is shaped by the distinctive logic commonly found in movies of the perestroika era (think of films like "Console My Sorrows" or "The Humble Cemetery"). Additionally, Karpikov pays homage to his cinematic mentor, Sergey Solovyov. The romantic narrative bears some resemblance to "Assa," even featuring the telltale joint photograph reminiscent of the one shared by Bananan and Alik, as well as an eccentric African-American character.

Throughout the story, Zhaken never finds a true refuge, yet he clings to his freedom and the memories of a poignant, unanswered question posed by his unrealized love interest: "I loved. Where did it all disappear? Do you happen to know?"

"Little fish in love" (1989) Directed by Abai Karpykov

"The Land of Our Fathers" (1966)

Director: Shaken Aimanov

In the first summer after the war, an elderly Muslim man (Elubai Umurzakov) embarks on a train marked "Leningrad to Kazakhstan!" His mission? To retrieve his fallen son's remains. Accompanying him is his grandson, Bayan (Murat Ahmadiev), who believes that in Moscow, there are cafes where the entire menu consists of ice cream. With the grave already prepared, the task remains to bring the remains home. Along the way, the grandson gets separated from his grandfather. Upon their eventual reunion, both realize that life’s expansiveness reaches far beyond the train's simple back-and-forth movement.

In the realm of Kazakh cinema, the remarkable "The Land of Our Fathers" brought to life from the script by Olzhas Suleimenov, holds a significance akin to that of "Tokyo Story" (1953) by Yasujirō Ozu for Japanese cinema and even for global cinema at large. Much like "Tokyo Story," this film revolves around a journey.

Trains, tracks, and roads—integral motifs in Kazakh cinema—are exemplified in numerous instances. "The Needle" opens against a backdrop of railway tracks. "Three Brothers" sees children embarking on a train journey. The finale of "My Lucy's Sister" features a boy and his dog running along a sunlit railway embankment toward his childhood friend. "Shuga" by Darezhan Omirbayev adapts elements from "Anna Karenina," beginning with action at the Almaty station. In "The Gentle Indifference of the World," characters meet near railroad tracks. In fact, as early as 1929, a film titled "The Arrival of the First Train in Alma-Ata" was shot here.

In "The Land of Our Fathers" the journey takes on an initiatory aspect, a confrontation with mortality. As the characters travel to a funeral, their fellow traveler—an archaeologist—carries a human skull. The train passes through a quarantined plague zone. In the film's conclusion, when the boy finds a communal grave and performs an ancient ritual, he realizes the interconnectedness of existence. The revelation dawns that every path is a path homeward, regardless of its direction.

"The Land of the fathers" (1966) Directed by Shaken Aimanov

"The Dove’s Bell-Ringer" (1993)

Director: Amir Karakulov

In an abandoned rural house, where rain seeps through the roof, he (Chingiz Nogaybayev) and she (Elmira Makhmutova) find shelter. With a crowbar, he breaks a hole in the wall, and she drops a bucket into a well. Together, they sit by the campfire at night as if they were the last inhabitants on Earth. Beyond their haven, the outside world remains mundane, except for vague street fights accompanied by a tune by the band "Musicola. " It's as if the external world barely exists. This couple's universe revolves around their dovecote and mutual love, and that is all they possess. The idyllic setting shatters with the girl's tragic death during childbirth. He, alone, buries her in an empty graveyard and continues to brew tea for her as if she's still alive. Gradually losing his sanity, he becomes entangled in a fight and ends up in prison.

Much like "The Separation," this is also a loose adaptation, inspired this time by Faulkner's "Black Harlequinade." As the director confessed, "In the original, the ending was different—after losing his wife, a hefty black man hangs himself on the bell tower of a white church. But that didn't fit here, as we lack churches and bells. So, I came up with the idea that he goes slightly mad and starts chasing pigeons, though it's weaker than Faulkner's." Perhaps the ending is less potent than Faulkner's, yet Karakulov's chronicle of near-silent love with its extended vacant shots finds few equals. Impoverishment is characteristic of his poetics, seen in "The Separation" and later in "Jylama!"

In this role, Elmira Makhmutova evokes heroines from early cult films by Hal Hartley, who commenced his career around the same time as Karakulov, particularly reminiscent of actress Adrienne Shelly.

An Italian review aptly stated, "The film received one of the two Grand Prizes at the Taormina Film Festival, but its chances for box office success seem doubtful." Indeed, that's how it turned out, yet it's worth noting that the chairman of the jury in Taormina at the time was Quentin Tarantino.

"The dove's bell-ringer" (1993) Directed by Amir Karakulov

"Crossroads" (1963)

Director: Shaken Aimanov

Galina (Farida Sharipova), a beautiful divorced doctor, insists on responding to an urgent call, despite her car's having a malfunction. She saves a patient's life, but on the return journey, the ambulance driver, Medvedev (Leonid Chubarov), due to that same system failure, fatally strikes a drunken pedestrian. Although the driver receives a suspended sentence, Galina is appalled by even this lenient verdict, especially since the judge is her lover.

This film is a classic example of a court trial drama typical of the 1960s Soviet Union. It can be grouped with films such as "The Man Who Doubts" or "Accused of Murder."

At the heart of the story is an ethical debate about the innocence of a person, the intriguing balance between law and conscience, and whether a noble act could actually be considered breaking the law (in this regard, Aimanov - possibly the most acclaimed and versatile director of Soviet Kazakhstan - subtly touches upon themes resembling "Beware of the Car!").

However, what's truly captivating is the underlying depiction of society's latent matriarchal power. The protagonist of "Crossroads" exudes authority and assertiveness, almost reminiscent of a Hong Kong aristocrat. She is a single mother raising her daughter, keeping the true identity of the father - a drunkard and decadent (brought to life brilliantly by Vladimir Soshalsky) - hidden from her. He often drops statements like "faith in humanity is as much of a deception as any religion." Ultimately, it is her decision to undertake a journey that leads to a person's tragic end.

In "Crossroads," men, regardless of their positions and trades, merely serve as functionaries and shields for the true laws of the world order. They can drive a car, father a child, or preside over a court, but at life's crucial intersections, women regulate everything.

Galina directly challenges Judge Iskander (Asanali Ashimov, who later starred as the spy Chadiyarov in the trilogy, see "Trans-Siberian Express" in this list) during the trial, essentially applying sexual pressure on the court. The wife of the killer chauffeur calmly visits the victim's widow, and they instantly get along. In fact, the uncompromising judge is eventually compelled to humble himself before his spirited fiancée.

As the little girl rightly states in the film, "Mom is always right."

"Crossroads" (1963) Directed by Shaken Aimanov

"A Place on the Grey Tricorne" (1993)

Director: Ermek Shinarbayev

In the early 1990s, an unnamed young nihilist (Adilhan Yesenbulatov) roams the city, writing plays, casually engaging with intelligent and lovely girls—one of whom he kicks around —and ironically, she asks him for forgiveness. He lies in bed like Belmondo in "Breathless," proclaiming that life demands courage. He listens to Maria Callas interspersed with the "Bamov Waltz" by "Samotsvety." The chronicle of this underachiever concludes with a non-lethal overdose of pills.

Winner of the "Golden Leopard" at the Locarno Film Festival, this film begins with one of the longest scenes (if not the longest) of rolling joints and subsequently smoking them in world cinema. "I don't see joy in anything," the protagonist admits. However, despite his anhedonic disposition, the film itself is rich in concealed lightness and joy. It is an existential variation on the theme of "I'm Walking, Strolling Through Almaty," but with Eastern equanimity. When posed with the question, "Which do you prefer - Almaty or New York?" the resolute answer is, "Almaty, it's calmer here.

The film is generously seasoned with cultural allusions. It opens with an epigraph from Roger Vitrac; characters watch "Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom" on television (one wonders how such a film was screened in Almaty in 1992), discuss Mismi, and quote Nietzsche's "The Gay Science" regarding life being inherently valuable, with its outcomes merely a free add-on. This sentiment aptly describes Shinarbayev's film, where nothing much happens except the manifestation of cinematic magic.

"The place on a grey tricorne" (1993) directed by Ermek Shinarbayev

"His Time Will Come" (1957)

Director: Makhambet Utemisov

The film's genre is introduced by an off-screen voice as the life and wanderings of Chokan Valikhanov (Nurmukhan Zhanturin). In truth, Valikhanov, a remarkable scholar and ethnographer who discovered the "Manas" epic, appears primarily as a wanderer in this story, embodying a messenger from the future rather than the present, as the title suggests. He finds a sense of belonging only in the vast expanse of his native steppe. Uniforms, whether a Russian army officer's or a merchant's attire during a journey to Kashgar, don't make him feel truly at home. His dialogues span across generations—debating with his father, Dostoevsky, Alexander II, and even himself.

While it adheres to familiar Soviet biopic conventions, the film remains captivating to this day for several reasons. Firstly, the quality of its direction—comprising grand performances and substantial directing. Kirill Lavrov even makes a brief appearance, although some, like director Sergei Gerasimov, believed that Kazakh actors were more captivating. Secondly, despite its clear political engagement, the film delves into controversial historical issues, notably the idea that colonialism benefited local elites from noble families. As one character notes, "I now wear the Russian uniform. Let it hang on me like a sack on a camel. But as long as it's comfortable, I won't take it off."

Valikhanov grapples with a dilemma—facing imperial powers on one side, opportunistic nationalists on another, and hypocritical Englishmen on yet another. Even the seemingly progressive Russian officers, whom Valikhanov joins on a military campaign, turn out to be colonizers. What's labeled as a "civilization campaign" is, in reality, an exploitation of Central Asian resources and the annihilation of peaceful inhabitants.

In 1984, Asanali Ashimov created another film about Valikhanov titled "Legendary Chokan," an interesting work that, however, remained overshadowed by Begalin's masterpiece.

"His time will come" (1957) Directed by Mazhit Begalin

"Toro" (1986)

Director: Talgat Temenov

The young boy Toro (Aikyn Kalykov) lives in a village with a stern stepfather (Bolot Beyshenaliev) who beats up on him. Toro and neighboring children play soccer for money. One day, Toro's team demands that he steal money for the game. Toro takes the penalty shot, leading his team to victory, but now he must return the money to his stepfather's suitcase under the bed before he returns.

This elementary short film is like a small revelation and encapsulates key motifs of future Kazakh cinema: childhood, violence, indifferent nature, ritualistic play, the triumph of victory, money, loneliness, sepia tones, and even classical music— Ermek Shinarbayev uses Maria Callas, here performing Bizet's opera. The solitude of each character is accentuated by the absence of their personal history; they live here and now in the frame, and there is no need to know anything more about them.

Like many representatives of the new Kazakh wave, Talgat Temenov is also a graduate of S.A. Solovyov's workshop. Later, he would direct the notable film "The Running Target" (1991) about an event in December 1986, with Nonna Mordyukova in a major role.

"Toro" (1986) Directed by Talgat Temenov

"Where the White Mountains Are" (1973)

Directors: Viktor Pusurmanov, Askhat Ashrapov

Cantankerous retiree and war veteran Myrgazaly (Nurmukhan Zhanturin), who claims that "honesty replaced joy" for him, is not fond of people, including his wife and city-dwelling daughter (Natalia Arinbasarova). His main delight is a white female camel. He refuses to let her join the village's herd, despite his neighbors' pleas. They suggest cutting the tendons around her eyes to make her receptive to a mate and yield milk. When Myrgazaly ends up in the hospital, the camel is operated on. As a result of the vivisection, the camel goes blind. In the finale, the old man, with the grandeur of Lawrence of Arabia, releases her with her newborn calf back to her home—the white mountains that she can no longer discern.

This film is poignant, unconventional, and mystical. In Soviet cinema, camels usually appeared for comedic or circus purposes—recall the spitting scene in "Gentlemen of Fortune" (1971) or Yurkovsky-Bender riding a desert ship in "The Golden Calf" (1968). The tearjerker trend of animal films in the USSR would come later—neither "White Bim Black Ear" (1977) nor "Don't Shoot the White Swans" (1980) had been released yet. In this regard, Pusurmanov's film can be considered one of the most significant (though largely unnoticed) milestones of lyrical animism in cinema.

The thematic submission of the animal and the human reaches its peak in the scene where they lead the camel to a blind sacrifice, accompanied by funeral chorales. The film masterfully plays with the mournful symbolism of the color white, a motif common in many Eastern cultures, and it is emphasized by Robert Rozhdestvensky's "Ballad of Colors." Beyond the screen, Innokenty Smoktunovsky's voice narrates. About ten years later, Erken Shinarbayev invited him again to "Kazakhfilm" to voice the film "My Sister Lucy" (1985). However, what's most surprising is that in Moscow in 1973, this film was shelved after someone “discovered” a reference to the mass emigration of Soviet Jews to Israel supposedly conveyed through the camel's escape to the white mountains.

"Where the mountains are white" (1973) Directed by Viktor Pusurmanov, Askhat Ashrapov

"The Ballad of Manshuk" (1969)

Director: Majit Begalin

The film portrays the final day in the wartime life of Manshuk Mametova, a twenty-year-old machine gunner and Senior Sergeant from Almaty. She is pursued by Lieutenant Yezhov (Nikita Mikhalkov), a witty scout sporting a woman's watch. The military reality intertwines with her reminiscences of civilian life, Kazakh-language songs, and pre-death visions.

This classic Soviet film is worth revisiting today for three compelling reasons.

Firstly, it offers a refreshingly honest depiction of war, devoid of clichés. It portrays warfare as a process where comrades tragically sacrifice lives, soldiers vent their frustrations at the leadership, and even heroic deeds fade into the mundane.

Secondly, it delves into the gender challenges faced by a female sergeant, referred to aptly as a "sergeantess," in a wartime setting within a predominantly male environment. Her fellow soldiers taunt her with colloquial terms like "the braid" and "crazy chick," while commanders engage in earnest debates regarding the factors that led Manshuk to war - whether it was an intense desire to suppress her femininity or, conversely, a strong maternal instinct.

Thirdly, the character of Manshuk embodies Kazakh traditions. For her, the birth of a lamb is a sacred event, and she nourishes her fellow soldiers with apples from Almaty. In her sacred consciousness, everything, even the "Maxim" machine gun, appears imbued with life.

Lastly, the film is worth watching solely to hear how Mikhalkov pronounces the word "beshbarmak," a traditional Kazakh dish.

"Song About Manshuk" (1969). Directed by Mazhit Begalin

"Blue Route" (1968)

Director: Zhardem Baytenov

Korik (Marat Duganov), a young hydrogeologist with a penchant for adventure during the era of mineral exploration, takes up an internship with two rugged workers. The trio embarks on a journey across the rough roads of the Mangyshlak region to collect water samples. During a stop at a yurt, they encounter runaway criminals with money stolen from their expedition. Among them is a colorful leader-wordsmith whose panicked cry of "Police!" emphasizes the first syllable.

Director Zhardem Baytenov, who later mainly worked on children's films like "The Quartet for Singing" and "Snowdrops," demonstrated the full spectrum of human passions in his debut film, scripted by Olzhas Suleimenov.

This is a very unsettling black-and-white film, with a shaky camera and a harsh narrative, somewhat reminiscent of American road noirs like "They Drive by Night" (1940). Simultaneously, his storytelling carries echoes of Shukshin and Shpalikov.

Initially, Korik's companions are indistinguishable from the criminals - they begin by brutally beating their intern for being a "hipster." One of them, a psychopathic driver with a complex about being born out of wedlock, genuinely "sulked for three winters" over his struggle with religion. In other words, he hit a mullah.

Korik goes through not just a school of life but a school of existence. When the characters find themselves at a nighttime feast with lamb and vodka in the yurt, it seems as though time has long stopped here, giving rise to the image of the ancient epic horse, Tulpar. The boundless steppe appears as a space free from any state or human laws and conventions. "The land is from the devil, water is from God, and here the water is from the devil," one of the characters muses. The only remnants of the Soviet system here are the half-empty shelves in the store, and a surrealistic effect is created by Salvatore Adamo's song "Goodbye, My Love" playing over the desert landscape (a very Shpalikov-like touch).

"The Blue Route" (1968) Directed by Zhardem Baitenov

"Mariam" (2021)

Director: Sharipa Urazbayeva

Mariam (Meruert Sabyusinova) loses her husband and the father of her four children. To survive, she needs a certificate of the breadwinner's death. A schoolmate and police officer offers to help with a familiar corruption scheme—money in exchange for proof of death. Unexpectedly and without explanation, Mariam's husband returns, and now she has to somehow repay the already spent monetary aid.

A plot that in other films often served as a subject for farce transforms into icy tragedy here. The title is reminiscent of Truman Capote's early story "Miriam," but where the horror flourishes with lush colors and white silk dresses in the works of the Louisiana classic, Urazbayeva's film encapsulates everything in a single line: "Now you're dead." The film was shot in five days, on the thinnest but vibrant thread—silent dinners, a plastic tablecloth with pineapple patterns above the sink, airplane ice in an empty sky, a sheep slaughter (a scene exactly like in the agonizing film "Harmonica Lesson" by Emir Baigazin). Sharipa Urazbayeva, a delicate chronicler of female subjectivity (see also her new film "Red Pomegranate"), undoubtedly adheres to the ascetic minimalism of the new wave representatives, ranging from Aprymov to Karakulov but adds an inexorable social layer that, in turn, grows into fate and myth. "Where were you?" Mariam only asks her husband to receive the answer, "It doesn't matter," and she folds into the familiar shape of a question in the snow under a neutral sky.

"Mariam" (2021). Directed by Sharipa Urazbayeva

"The Balcony" (1988)

Director: Kalykbek Salikov

Set in the early 1950s, in Almaty, the story follows a young man named Aydar, nicknamed Sultan (Ismail Igilmanov). He's a poet, a fighter, and a dreamer who leads a group called the "Twenty" in his yard. Defending boyish values, he listens to a phonograph on his third-floor balcony, teases a young teacher, rides a white horse, and befriends Suncatcher, an artist (Valentin Nikulin as Sergey Kalmykov), who imparts an essential lesson: "Fear the crowd, my friend."

In the vast realm of existence, two divergent paths beckon: one offers a panoramic view from lofty perches like balconies and gallant steeds, while the other plunges headfirst into life's intricate labyrinth, immersing in its essence—the courtyard well, the neighborhood's stories, the allure of a Walter firearm, and the enigmatic Kashgar Anasha. And thus, "The Balcony" artfully intertwines these two perspectives, forging a cinematic symphony of complexity.

A perceptive physician within the film remarks, "It's as if you don't belong to our reality." Indeed, "The Balcony" boasts an ethereal texture, where reality often dissolves into the ethereal. A nocturnal tram ferries statues of Abai and Pushkin, Descartes' gaze adorns a school wall, while a flock of sheep ambles beneath Stalin's iconic visage.

In the illustrious cinematic year of 1988, the screens witnessed the emergence of “Needle" and "The Balcony," twin jewels from the realm of Kazakh cinema. While " Needle" dazzled with its innovative flair, "The Balcony" emerged as a more traditional but equally captivating creation, lurking in the shadows of its counterpart. Beneath their differing façades, a common thread unites them: a tenacious young protagonist, the gritty world of crime, the haunting specter of narcotics, and a climactic procession through a snow-laden alley.

As the musical notes of Schnittke and Gubaidulina resonated through "The Balcony" in '88, their enchanting melodies found an echo that, while not as immediate as the iconic "Blood Type," unfurls into an enduring auditory tapestry. In the present, a mesmerizing psychedelic funk escorts a street gang on their evanescent journey through a tunnel under the bridge—a musical encounter more intriguing, perhaps, than the straightforward melodies of the rock group "Kino" .

In its totality, "The Balcony" emerges as a resonant ballad of youth, a poignant reminiscence that culminates with a poignant echo echoing Vysochansky's sentiment: "Because those corridors seemed like a more convenient route to ascend." In this cinematic tapestry, the echoes of childhood reverberate, unveiling a narrative rich in layers and nuanced emotion.

"Balcony" (1988). Directed by Kalykbek Salykov

"Sweet Juice Inside the Grass" (1984)

Directed by Aman Alpiev, in collaboration with Sergei Bodrov

"Suyrik" is a type of grass that holds a sweet juice within it. It's also the name given to a young man's grown-up daughter—a fourteen-year-old eighth-grade chess enthusiast named Gulshad Omarova. She grapples with her first unrequited love for Marat, a boy from her class. The arrival of Natasha, a new student with irresistibly chubby cheeks, on the first day of school intensifies her feelings.

Late Soviet films that delve into the lives of high schoolers during their fleeting days after childhood are like a distinct Atlantis, and "Sweet Juice Inside the Grass" reigns supreme on this cinematic isle. Perhaps, it stands as the most heartrending film from Kazakhstan, even though it was shot on the shores of Lake Issyk-Kul. Here, you can palpably sense that same poignant yearning for childhood seen in works like Sergei Solovyov's "Heiress in a Straight Line" (1982). Just like Solovyov's characters, the protagonists here also read Lermontov—not "Masquerade," but "Mtsyri." There's even a poetic battle, where Natasha, the rival seeking to separate the young couple, recites Lermontov, and Suyrik retorts with Tyutchev.

All that Afro-American writer Maya Angelou termed "poetic existence" is beautifully encapsulated in their dialogues:

- What are you doing here?

- Just enjoying life.

- How about we have champagne?

- They don't serve champagne to kids.

This is a nuanced saga of a lost paradise, where October nights invite clandestine swims, where snowball fights can be had with sisters in the small courtyard, where a horse grazes in the fog, warmed by a father's love. Camel effigies are paraded through the streets, and twenty kopecks are buried in the ground like hidden treasure. For the world, it's as though a time beyond seasons has arrived, and the memory of it is encapsulated in simple words: "When I was 14 years old, we lived in a small town near the border, and everyone loved me very much back then."

"Sweet Grass Juice" (1984). Directed by Aman Alpiev, Sergey Bodrov

"Goliath" (2022)

Directed by Adilkhan Yerzhanov

In the fictional village of Karatas, a gangster named Poshaev (Daniyar Alshinov) reigns supreme, wielding an AK-47 wrapped in tape. He's known for more than just beheading enemies—his reputation extends to targeting their wives, children, and parents. When he murders a daring journalist, he attends her funeral to inform her ex-husband, Arzu (Berik Aitjanov), of his crime and to gauge whether the widower seeks revenge. The confrontation between an ordinary man and a formidable criminal unfolds in a slow, hypnotic duel on the unforgiving terrain.

The film opens with an epigraph from Machiavelli about revenge, yet the narrative goes beyond a personal samurai conflict. Within it, an ordinary, crippled stutterer transforms from a mere character into a hero. Director Yerzhanov has conjured up the fictional village of Karatas, reminiscent of how William Faulkner created Yoknapatawpha County. Much like Faulkner's works, the story delves into cosmic fundamentals. In Karatas, blatant evil prevails, jeeps resemble wild steppe creatures, and people are killed over trivial possessions like refrigerators.

"Goliath" unquestionably serves as a thematic counterpart to Andrey Zvyagintsev's "Leviathan," paralleling the way Nurtas Adambay's "Taraz" pairs with Peter Buslov's "Boomer." However, in both cases, the Kazakh versions are distinctly grittier and more desperate. Foreign capitalists make their appearance, engaging in conversations about America and Europe, but only as they relate to the afterlife. The pervasive theme is one of oppressive power, as illustrated by Poshaev's authority. A sense of ceaseless despair and violence hangs in the air. The film's grand finale strikes a balance between the late Guy Ritchie's style, classic Melville, and Soviet westerns reminiscent of Samvel Gasparov's works.

Yerzhanov directs prolifically and with stylistic diversity, but it's arguably in "Goliath" that he emerges as a true dramatic poet—expressing others' emotions while remaining silent about his own, as Reskin suggests.

"Goliath" (2022). Directed by Adilkhan Yerzhanov

"Needle" (1988)

Directed by Rashid Nugmanov

A mysterious figure named Moro (Viktor Tsoi), clad in darkness, strides purposefully toward the train station, serenaded by the haunting melody of his own song, pondering the concept of dying young. Embroiled in past affairs of old Almaty, he seeks to collect on unpaid debts and attempts to rescue his girlfriend Dina (Marina Smirnova), ensnared by drug addiction. However, his journey ends tragically with a stabbing wound on the snowy path of Tulebaev Alley. "He came - he left" — this structure underpins the dramatic narrative of one of Kazakhstan's most renowned films.

In essence, Rashid Nugmanov fashions his distinctive interpretation of Jean-Luc Godard's "Breathless." Like its Godardian predecessor, this film remains perpetually fresh and immune to the passage of time; the posthumous aura of Chekhov finds equilibrium amidst snippets of children's radio dramas, and conversely, postmodern artistic nuances are masterfully executed through Moro's calculated samurai-like gait. Despite numerous treatises exploring the impact of French cinema on the Kazakh New Wave, the receptive essence of "The Needle" still astonishes with its ingenious references. For instance, the scene where Dina dons a white mask seems to hark back to Georges Franju's "Eyes Without a Face."

Tsoi introduces a new archetype – an efficient yet detached persona almost bordering on autistic. Critics drew parallels between him and Camus' "Stranger" (themes that would later inform Adilkhan Yerzhanov's "Tenderness of Indifference to the World"). "The Needle," at its core, delves into what unfolds when an outsider takes a stand for someone, irrespective of the reasons why.

Throughout history, identifying a rock star who traversed the silver screen with a comparable magnitude to Tsoi is a challenge. He only left behind two cinematic legacies, both profoundly significant: "Assa" and "The Needle." Tsoi's presence propelled the film to unprecedented heights (he held the title of the Soviet screen's actor of the year), yet his own iconic status (particularly after his tragic demise) somewhat eclipsed the film's cinematic architecture. Tsoi's symbolism grew mightier than all other embedded meanings. Nonetheless, popularity was indeed one of those meanings – after all, the film is dedicated not to Godard but to Soviet television.

"The Needle" (1988) Directed by Rashid Nugmanov

"Amangel'dy" (1938)

Directed by Moisey Levin

The screenplay for the first Kazakh sound film was written by one of the "Serapion Brothers," writer Vsevolod Ivanov, a native of Semipalatinsk. The film portrays the life of hunter Amangel'dy Imanov (Yelyubay Umurzakov), who escaped from captivity in 1916 and led a Central Asian uprising against autocracy.

"Amangel'dy" stands as a prominent example of socialist realism, reminiscent of the works of artist Kasteyev. Like any piece of socialist realism, three elements are crucial: national identity, ideology, and specificity. The film's uniqueness is its strong suit, and given that less than twenty years separate the real Amangel'dy's death from his cinematic portrayal, the movie exudes a documentary-like atmosphere.

Director Moisey Levin, formerly a theatrical artist and constructivist, skillfully captures the essence of spontaneous movement. This is especially evident in the film's opening scene, where Nicholas II's decree from June 25, 1916, announced the so-called requisition—calling upon local residents for trench work on the home front. For the local nomads, the order to dig the earth was particularly degrading, as they sometimes volunteered for war, but only in the cavalry units: "They took away our steppe, and now they say: go defend the steppe!"

When Russian political prisoners discuss Lenin with Imanov, they emphasize his Swiss background: "In a beautiful mountainous country, much like yours" (Kazakhstan would later be compared to Switzerland in Shaymanov's "Angel in a Fur Cap" (1968)). In response, Amangel'dy expresses regret that Lenin fled from the czar to Switzerland instead of Kazakhstan, where he could have hidden him so well among the reeds that he wouldn't be found. This unintentional and prophetic portrayal touches on Kazakhstan's role as a haven for Russian refugees, from the era of evacuation to the current influx of relocators.

In the film, Amangel'dy himself bears a resemblance to Lenin (which is not surprising, considering that actor Umurzakov was also the first performer of Lenin's role on the Kazakh stage).

"Amangeldy" (1938) Directed by Moses Levin

"Ferocious" (1973)

Directed by Tolomush Okeev

An orphaned boy (Kambar Valiyev) lives in a mountain village with his grandmother and uncle (Suymenkul Chokmorov, dubbed by Armen Dzhigarkhanyan). The uncle attempts to mold him into a fighter and hunter, yet the boy refuses to throw the first blow and, more so kill. He rescues a wolf cub named Kokserke from certain death. Just like a wolf, he prefers not to dwell among humans, instead departing the village and settling at the graveyard – near the presumed graves of his parents.

This adaptation of Mukhtar Auezov's story departs from the typical sentimentality found in Soviet films depicting human-animal relationships. With its severity and unwavering nature, it more closely resembles Cormac McCarthy's American novel "The Crossing," which tells the tale of a wounded she-wolf. The inevitability of humans killing the wolf is juxtaposed with the wolf ultimately taking with her the sole creature that loved her.

The theme of the boy and the wolf will be revisited in the film "A Wolf Cub Among People" (1988) by Talgat Temenov, but Okeev's film remains unmatched in its portrayal of the shared desperation between the child and the creature. The film's central question, "Where can kindness be found ?" – not only remains open-ended but fundamentally without an answer.

The film was crafted at "Kazakhfilm" by the talented Kyrgyz director Tolomush Okeev and was nominated for an Oscar from the USSR, though without success. In our current era, its chances of receiving recognition would likely have been greater.

"The Ferocious One" (1973) Directed by Tolomush Okeyev

"An Anxious Morning" (1967)

Directed by Abdullah Karsakbayev

Soviet authority marches through Semirechye, yet one of its most active enforcers, Commissioner Baytenov (Idris Nogaybayev), ends up imprisoned due to false accusations of nationalism and counter-revolutionary conspiracy in Verny. He shares a cell with Bay, who holds anti-Soviet views, and they both confront an uncomfortable question: "Why did you kill my comrades, and why did I kill yours? I don't understand."

Director Abdullah Karsakbayev, once an extra in Eisenstein's "Ivan the Terrible," later directed one of the most well-known Kazakh children's films, "My Name is Kozha."

In his recent monograph on Kazakh cinema during the Soviet era, American researcher Peter Rollberg notes that Karsakbayev managed to depict the totalitarian essence of the emerging Soviet authority despite censorship. Indeed, within specific scenes of "A Restless Morning," audacious questions emerge: Is Soviet rule truly indispensable for Kazakhstan? Does it resonate with the local consciousness? How does it rationalize horse theft etc.? At times, these queries are presented humorously ("A Russian law was passed: all Kazakhs can eat grass, it's called cabbage. And what's wrong with Russians? They build wooden houses, raise pigs. Is a pig inferior to a ram? God created pigs too!"). Nonetheless, the film's overall structure retains profound seriousness.

Commissar Baytenov, beyond his Red Guard ambitions, also becomes a symbol of national consciousness. He studies petroglyphs, asserting, "Who remembers, lives," and, resembling epic heroes, ritually cleanses himself in a mountain stream. This facet becomes particularly poignant when compared, for instance, to "White Sun of the Desert," shot around the same time. The notorious Comrade Sukhov is merely a passing Russian Bolshevik, grappling with incomprehensible natives on his way to Katerina Matveyevna. In essence, it's because of him that Gulychatai, Vereshchagin, Petrukha, and the director of the local history museum meet their end while he continues onward, reminiscent of Pechorin. In "A Restless Morning," the dynamic is precisely the opposite: the wounded Baytenov tirelessly ascends a mountain, seemingly merging with his native landscape. Could it be that twenty years later, Nugmanov's "Needle" drew inspiration from that very powerful image?

The second part of our list of the best Kazakh films can be read here.

"Anxious Morning" (1967) Directed by Abdulla Karsakbayev