South Korea is a fascinating land of seeming contradiction. In this country, high technology—high-speed elevators, computer games, and cutting-edge art—exists side by side with ancient superstition and belief in the mystical world of spirits. This unique blend has created a culture that is both dynamic and deeply connected to its past.

Imagine you are walking down a hotel corridor in South Korea. You’re on the fourth floor, the same floor Koreans prefer to label with the letter ‘F’ to avoid the word four. This is because in Chinese, four is represented by a character that looks a bit like the character for death. Thus, this symbol has taken on an ominous significance throughout Southeast Asia, much like the number thirteen in Europe.

Suddenly, a girl in a white hanboki

Girls in traditional hanbok dresses. Bukchon Hanok Village. Seoul/Alamy

She comes closer. You can already see drops of blood dripping from the corner of her mouth. But then the elevator opens behind her and a crowd of young people, no less extravagantly dressed, rush out, laughing. Someone had just rented a room for a costume party dedicated to Korean myths.

However, you make a mental note to go to the shaman and ask for a ritual to appease any restless spirits—it’s a good insurance policy. After all, family stories about your aunt who died unmarried and was known for her ‘difficult personality’ might make you wonder if her spirit needs to be reassured.

Shamans and Christians

The idea of a person’s place in the world and what happens to his or her soul after death has been shaped in Korea for several millennia by the influence of at least a dozen religious and philosophical doctrines. Before literacy, animism and shamanism were the leading belief systems on the peninsula. Later, Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism came to Korea from China, and in the eighteenth century, Christianity also took root, with Catholicism first and later Protestantism. Today, the world’s major religions and many new sects coexist peacefully in the country, and religious syncretism has always been typical of the culture of Korea.

Christians are the largest religious group in South Korea, making up about 20 per cent of the total population, a fact that often surprises foreigners. In the most recent survey, 17 per cent of South Koreans identified as Buddhists and 2 per cent as followers of all other religions, including Islam. About 60 per cent of Koreans consider themselves atheists.

Around 20,000 South Korean Catholics attend a Mass near the demilitarized zone calling for peace between the Koreas, June 17, 2011/Xinhua/Park Jin Hee/Alamy

Confucianism as an official religion has all but disappeared in modern Korea. However, the entire system of government and Koreans’ ingrained notions of right and wrong are based on Confucianism. In the Middle Ages, its principles were the basis of the country’s government, and Korean jurisprudence can still be described as Confucian.

Female shaman carrying out a ritual dance for contacting ancestors/Alamy

At the same time, shamanism, called musok (무속), is making a comeback in Korea. According to the online platform Naver, there are about 16,000 organizations offering musok services in Korea. The cost of a one-hour consultation with a respected shaman is about 100,000 Korean won (37,000 KZT/70 USD), and the waiting period can be several months. The shaman’s job is to communicate with the spirits that most Koreans—atheists, Christians, and others—believe in. The traditional Korean religious beliefs are about honoring spirits (people, animals, places), and Korea’s original mythology is largely a description of struggle and cooperation with these spirits.

These were traditions that were practiced across Korea at one time, but they are obviously not observed in North Korea now.

Samguk Yusa

The main text of Korean myths and legends that has survived to this day is the Samguk yusa, or Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms. This five-volume collection of myths and historical accounts was compiled by the Buddhist monk Il-yeon at the end of the thirteenth century during the period of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla.

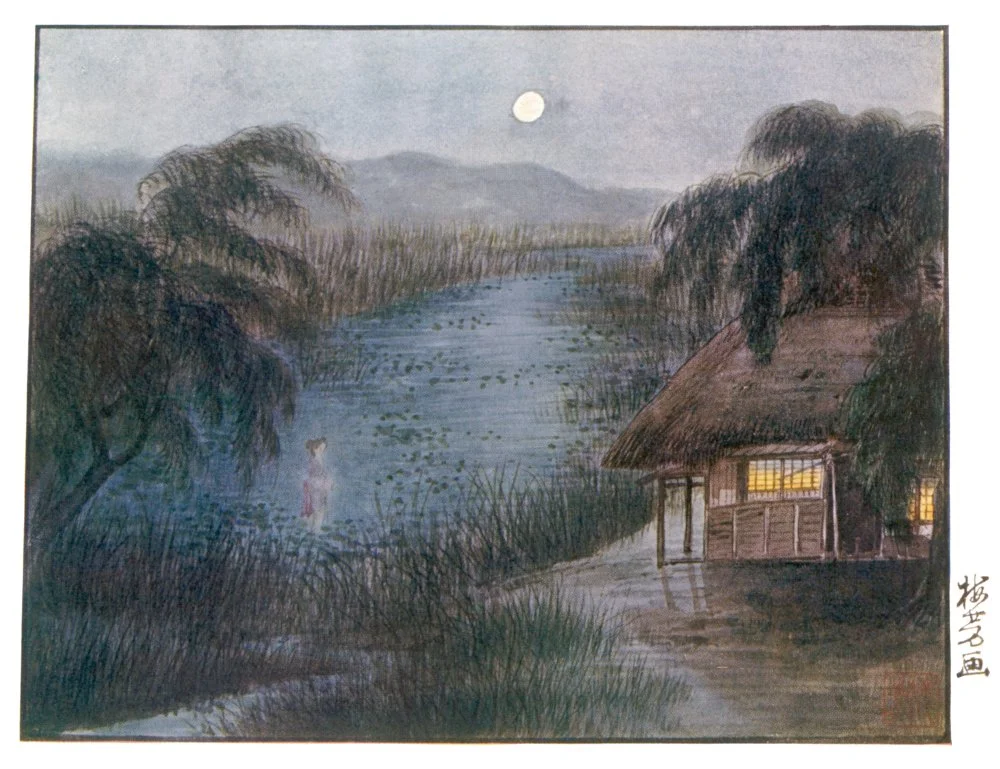

From the 'Hyewon Wind Speed Map', the director of the Kansong Museum of Art in Seongbuk-gu, Seoul/Wikimedia Commons

Samguk yusa’s legends are full of spirits and signs to be unraveled:

Wonsan once dreamed that he took off his headband, put on a hat of white cloth, and entered a well near Cheongwangsa Monastery with a twelve-stringed lute. When he awoke, he sent a man to fetch a fortune teller, who interpreted the dream:

‘You took off the headband—you will be deprived of your position; you took the lute—a cangue will be put on your neck; you entered the well—you will be thrown into prison.’

When Wonsan heard this, he was frightened and stopped going out of his house.

Still, most spirits are unfriendly to humans, and it would be wise to avoid any communication with them.

Gwisin and Dokkaebi

There are several types of ghosts in Korean folklore, and one of the most prominent being the gwisin, the spirits of the dead. These spirits linger in the world of the living for many reasons—they may take revenge on their enemies, protect their loved ones, or take care of people in general. However, they often simply take advantage of people to draw life force for their posthumous existence. Therefore, gwisin—even of close relatives—can become the cause of a person’s illness and death.

There are also spirits that were never human, such as dokkaebi (도깨비). These supernatural creatures are also known as ‘Korean goblins’ because they can both harm and help people. The dokkaebi can take on different forms and transform into both humans and animals.

Earthenware Patterned Tiles from Oe-ri, Buyeo - Landscape and Dokkaebi Design, Treasure of the Republic of Korea. National Museum of Korea/Wikimedia Commons

‘Is there anyone among the spirits who could become a man and help me with receptions and government affairs?’ the king asked Pihyon again.

Pihyon said: ‘There is one—Kjeldahl, who will be able to help you rule the kingdom.’

‘Bring him here,’ the king said.

The next day, Pihyon appeared with Kjeldahl. The king gave Kjeldahl a title and put him in charge of the kingdom’s affairs. He was indeed unmatched in loyalty and directness. At that time, the dignitary Lim Chong had no sons, and the king ordered him to make Kjeldahl his adopted son.

But one day, Kjeldahl turned into a fox and ran away.

Kumiho

Kumiho (九尾狐), the nine-tailed werefox, is another legendary creature in Korean folklore, much like a werewolf but taking the form of a fox. Unlike some mythical beings, it was never human. There is a similar character in the folklore of other South Asian countries, especially China and Japan.

Kumiho has lived in the world for a thousand years, growing stronger with each century. The fox can transform into a beautiful woman to seduce a man and eat his liver. It can also steal his soul, all to become even stronger and one day be reborn as a human.

Graveyards are a favorite hunting ground for these werefoxes. They roam them at night, digging up graves and eating human entrails.

Jeoseungsaja

Jeoseungsaja (저승사자), the grim Korean messengers of death, is a creature from the afterlife. He is very tall and wears a traditional black robe with puffy sleeves and a round black hat. His lips are black. In behavior, Korean grim reapers are more like government officials than cold angels of death. They can be bargained with: they will often consider the circumstances of the deceased, grant a reprieve, accept bribes, and sometimes help resolve problems with other spirits so that the dying can pass on to the next world in peace. Often, jeoseungsaja ‘work’ in groups of three, in which case they make decisions about a person’s fate as a group.

Figurine of a jeoseung chasa, a deity which in East Asian Buddhism and Korean shamanism brings the souls of the newly dead to the afterlife. Originally attached to a funeral coffin/Wikimedia Commons

Ghost Virgins

The most famous gwisin in Korea is the ghost of a girl who died a virgin, or chonyeo gwisin (처녀귀신).

A chonyeo gwisin is usually depicted wearing a white traditional hanbok outfit, with pale skin, blood dripping from the corner of her mouth, and loose hair.i

Sobok - White Hanbok. Тhe traditional mourning attire/Wikimedia Commons

The legend of chonyeo gwisin is associated with the Confucian view of a woman’s place in society. Confucianism taught Koreans strict hierarchy and order for the good of the state. The role of women was reduced to subordination to men and motherhood.

A girl who died unmarried had not fulfilled her feminine destiny and left this world with a sense of unfinished business. She was full of han (한), a Korean word for a complex emotion made up of anger, resentment, and regret.

Nagajuban (under-kimono) from Japan with a ghost design/Wikimedia Commons

Strong emotions at the time of death and an unfulfilled goal during life are the two basic conditions for the spirit of the deceased to become a gwisin.

A Healing Phallus

A chonyeo gwisin can be appeased by arranging a posthumous marriage ceremony between her and the spirit of a bachelor. Other protective measures could also be taken in advance. The most reliable one was to place a doll with exaggerated male genitalia in the coffin with the deceased.

In Korean villages, the coffin of a virgin was often buried upside down so that the chonyeo gwisin could not find its way out.

To appease angry spirits, Koreans also built phallus-shaped monuments for the same purpose. If a lost soul flew by, it would see the phallus, rejoice, and leave the living alone.

South Korea's Penis Park. Haesindang Park./Photo by Carl Court/Getty Images

Bachelor Ghosts

A mongdal gwisin (몽달귀신) is an evil spirit, usually obsessed with a woman, that attempts to possess her body out of lust. However, the spirit of a bachelor can be banished with a properly performed memorial service or a posthumous marriage ritual. But one should be very careful when choosing a shaman! A poorly performed ritual will only deepen the obsession of the mongdal gwisin.

Ghosts of the Drowned

A separate category of gwisin are the ghosts of drowned people. They are called mul gwisin (물귀신), or the water ghosts. Unlike the ghosts of bachelors and virgins, which often haunt the living in hospitals, schools, universities, and the such like, mul gwisin live in the water, usually in the same place where they were killed. Like many gwisin, they are angry and unhappy and will drag a stray traveler to the bottom if he is not careful. The tactics of mul gwisin has given Korean corporate slang a new term: you would be acting like a mul gwisin when you try to ‘drown’ your colleague.

Ghost Of O Sumi. Japan/Alamy

In 2020, the Korea Statistical Information Service (KOSIS) reported that 7.83 million out of 9.61 million Koreans aged 30 to 34 (81.5 per cent) were unmarried. It would seem that young Koreans are willing to risk becoming chonyeo gwisin and mondal gwisin.

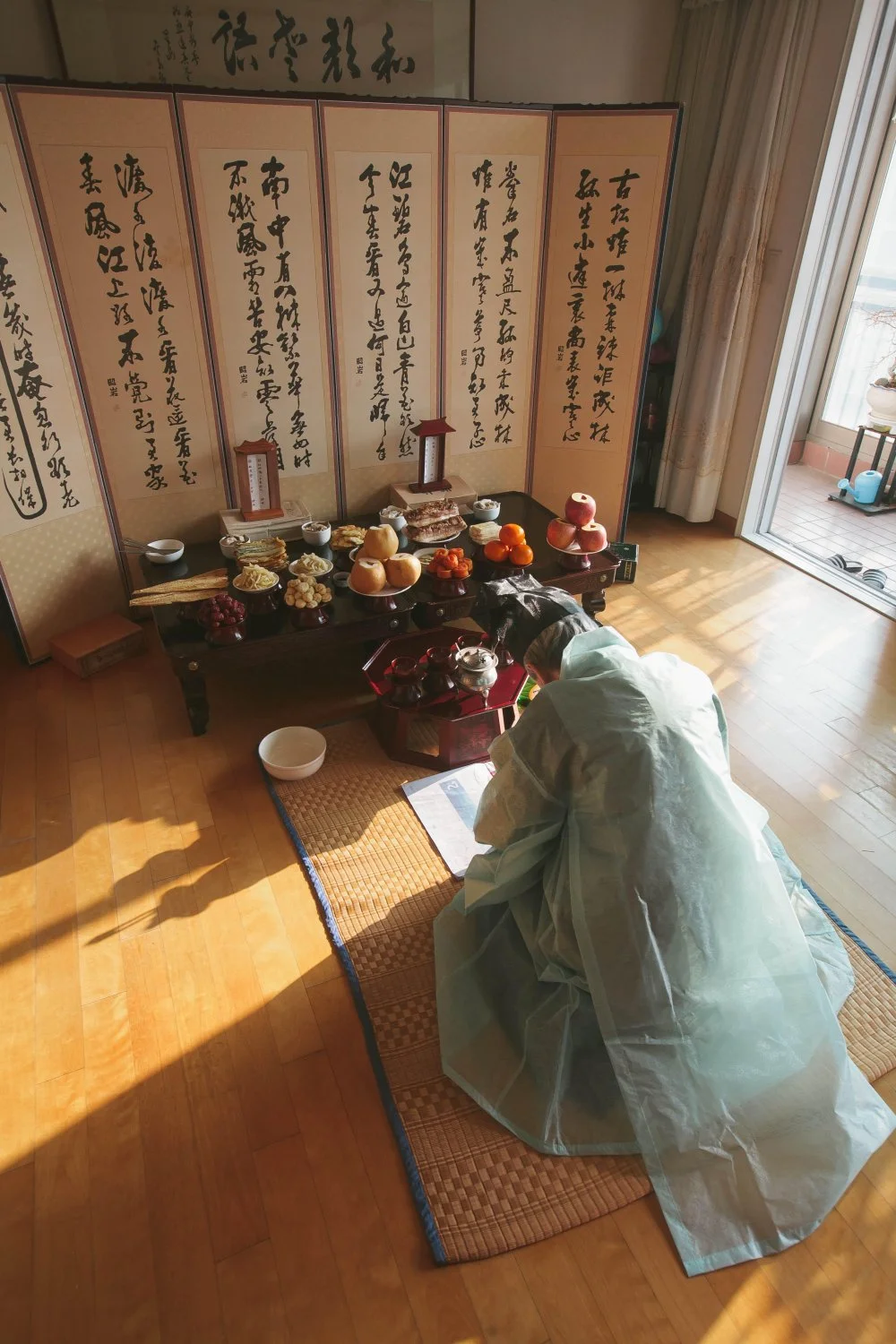

Jesa

In Korea, there are traditional rituals honoring ancestors designed to prevent their spirits from turning into evil supernatural beings called jesa (제사).

Over the centuries, the approach to the jesa has varied. In ancient times, it could be performed by both men and women. In the Middle Ages, the tradition was established that this rite was performed by the eldest son of the deceased or his eldest grandson, that is, the eldest son of his eldest son as the main heir. The Confucian custom of the eldest son receiving two-thirds of his father’s property, with the remainder divided among the other sons and the daughters receiving nothing, has survived in traditional clan villages.

Jesa ceremony during Korean new year/Alamy

In the cities, jesa is again performed by both men and women. It is performed on the eve of the anniversary of the death of a relative. The ritual consists of invoking the spirits of the ancestors, offering rice liquor and various foods, and the eldest son or grandson sticking a spoon in the middle of the rice bowl. The relatives then politely go outside to allow the ancestors to eat in peace.

Month of the Spirits

The seventh month of the lunar calendar, usually between late summer and early fall, is the month of the dead in Asia, including Korea. During this period, the activity of ghosts increases and one is more subject to bad luck. The Hungry Ghost Festival takes place on the fifteenth day of the month. Traditionally, Taoists and Buddhists perform special rituals to alleviate the suffering of the dead and protect themselves from their wrath. The Buddhist festival of Baekjung falls on the same day and has similar characteristics, with the purpose of honoring dead ancestors and making offerings to appease wandering souls.

River lanterns lit to celebrate the Ghost Festival in Guilin/Visual China Group via Getty Images/Visual China Group via Getty Images

In South Korea, ‘Ghost Month’ is a bad time for business. Many Koreans fear that starting new businesses during this time will result in financial losses, so business in Korea comes to a standstill during these days.