When you picture a ‘traditional’ national costume, from any part of the world, what comes to mind? Flowing dresses, ornate embroidery, tall headpieces? In Kazakhstan and across Central Asia, many of the outfits we have come to expect at folk festivals, in school performances, and even in museum exhibitions were not passed down from generation to generation. They were, instead, designed in the Soviet era, shaped by cultural policy and deployed as instruments of control.

Researcher Assiya Issemberdiyeva traces how this process of folklorization and the aesthetics of 'friendship of peoples' came to define what we now think of as national costume.

- 1. CULTURAL AND NATIONAL POLICY OF THE USSR: FROM MARXISM TO FOLKLORIZATION

- 2. THE ‘DECADE OF KAZAKH ART’: FOLKLORIZATION AS RECOGNITION

- 3. THE STAGE NATIONAL COSTUME AND THE ILLUSION OF TRADITION IN THE USSR

- 4. THE ‘FRIENDSHIP OF PEOPLES’ AND THE REPRESENTATION OF NATION THROUGH COSTUME

- 5. TRADITIONAL KAZAKH CLOTHING BEFORE THE USSR: VISUAL SOURCES AND REALITY

- 6. THE KAZAKH FILM-CONCERT: STAGE COSTUME AND THE FOLKLORIZATION OF CINEMA

- 7. DECOLONIZING CULTURE AND RETHINKING THE SOVIET LEGACY

CULTURAL AND NATIONAL POLICY OF THE USSR: FROM MARXISM TO FOLKLORIZATION

Imagine someone asks you the question ‘Who are you?’ By its very nature, it resists a one-word, or even a simple, answer because identity is not a singular construct—it is layered, complex, and shaped by many influences and experiences. And yet, history shows us that the Bolsheviks once attempted to reduce the essence of a person to a single denominator: social class.

As a theory, Marxism emerged in the context of Western industrial society, where class inequality, the gap between the worker and factory owner, was seen as the central social problem. However, when the Bolsheviks tried to apply this framework to the vast steppes of Central Asia, they not only overlooked local realities but also ignored the aspirations of various peoples who, for decades, had suffered racial or ethnic discrimination. And no matter how attractive the ideals of Marxism might have appeared on paper, they simply did not fit the lived experience of the Kazakh people.

At first, Bolshevik rhetoric included the claim that nations themselves were relics of the past, which would disappear in the march towards socialism. Yet, it soon became clear that without the support of local intellectuals, the regime could not consolidate power in the newly formed national republics. In the 1920s, to make nationally oriented elites trust them, the Bolsheviks made a temporary compromise: they promised a break with the colonial practices of Tsarist Russia and pledged to fight chauvinism.

Flag of Friendship. Banner representing the friendship of Soviet Nations. Moscow, Russian State Library / Alamy

In practice, however, the Soviet authorities’ strident revolutionary slogans hid a reality. Moscow was determined to maintain firm control over the former imperial borderlands, treating them as vital resources. This soon led to a conflict with local intelligentsia, including the first generation of Kazakh communists, who believed that the revolution would bring not only social but also national equality. Once it became clear these figures would not be fully bent to Moscow’s ideological line, repressions followed. The educated classes were decimated, and even loyal local Bolsheviks were swept up, many of whom had dared to believe the revolution would equalize not only rich and poor, but also the colonizer and colonized.

By the late 1930s, it was evident that despite the mass purge of intellectuals accused of ‘nationalism’—many of whom had simply demanded equality—the so-called national question was far from resolved. As a result, the Soviet authorities turned to a new strategy of diversion, which culminated in what became known as folklorization.

Joseph Stalin and Maxim Gorky in a small park on Red Square, 1931 / Wikimedia Commons

At the Congress of Soviet Writers in Moscow in 1934, Maxim Gorky declared that ‘in our time, folklore has elevated Vladimir Lenin to the status of a mythical hero of antiquity, rival to Prometheus’, urging writers to pay close attention to folklore, which was now redefined as the creative expression of the working class. From then on, folklore became an active tool of the regime: Lenin and Stalin were glorified in folk songs, a new Soviet mythology was manufactured with figures like Pavlik Morozovi

THE ‘DECADE OF KAZAKH ART’: FOLKLORIZATION AS RECOGNITION

The USSR’s folklore campaign expanded on an unprecedented scale after 1935, when Moscow launched a new series of cultural events: the Decades of Art of the Union Republics. Ukraine was showcased first (March 1936), followed by Kazakhstan (May 1936), Georgia (January 1937), Uzbekistan (May 1937), and others.

Hundreds of artists traveled to the capital in the hope of winning recognition from Moscow. These festivals, attended by Stalin and the Communist Party elite, were covered extensively in leading newspapers such as Pravda and Izvestiia. For the republics on the periphery of the USSR, participation became a source of immense pride.

Yet, what remains in post-Soviet memory as a triumph of national culture was, in reality, part of a sweeping campaign of Soviet folklorization—the selective staging of ‘national traditions’ under the watchful eye of the state, where authentic culture was celebrated only insofar as it could be stripped of political content and repurposed to serve Soviet unity.

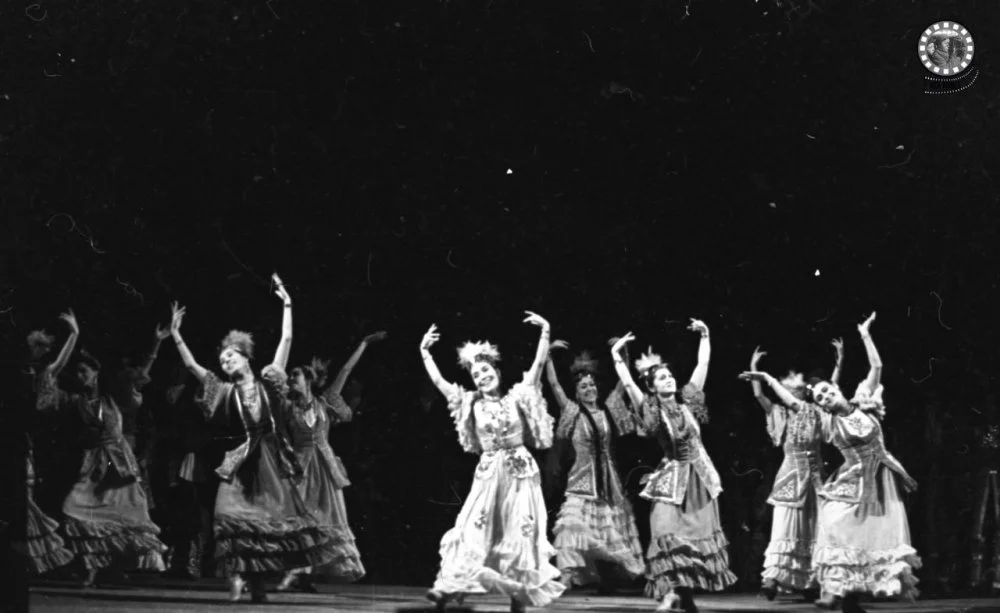

Roza Baglanova. Performance accompanied by the Kazakh folk instruments ensemble during the Decade of Kazakh Literature and Art at the Bolshoi Theatre of the USSR. 1959 / CSA CFDA RK

The Decades of Art were not only a showcase for national culture on a grand stage, but also a tool for systematizing, classifying, and ultimately governing nations. This pattern was strikingly similar to that of colonial states. In many ways, the Soviet Decades echoed the colonial exhibitions of the Western empires, particularly those in France and Britain.

Since the fifteenth century, Europe had cultivated the idea of its own ‘civilizational and racial superiority’ over ‘savage peoples’, often turning colonized communities into spectacles at fairs and exhibitions. The Industrial Revolution gave new momentum to such spectacles, culminating with grand World Fairs taking place in Paris (1855, 1867, 1878, 1889, 1900), and especially the 1931 Colonial Exhibition, where imperialism was celebrated openly and unapologetically.

Such events offered colonized peoples the chance to be ‘seen’ in the imperial center, but not in recognition of any genuine cultural diversity. Rather, they served to legitimize the colonial project itself, casting national traditions as colorful but ultimately subordinated contributions to the empire.

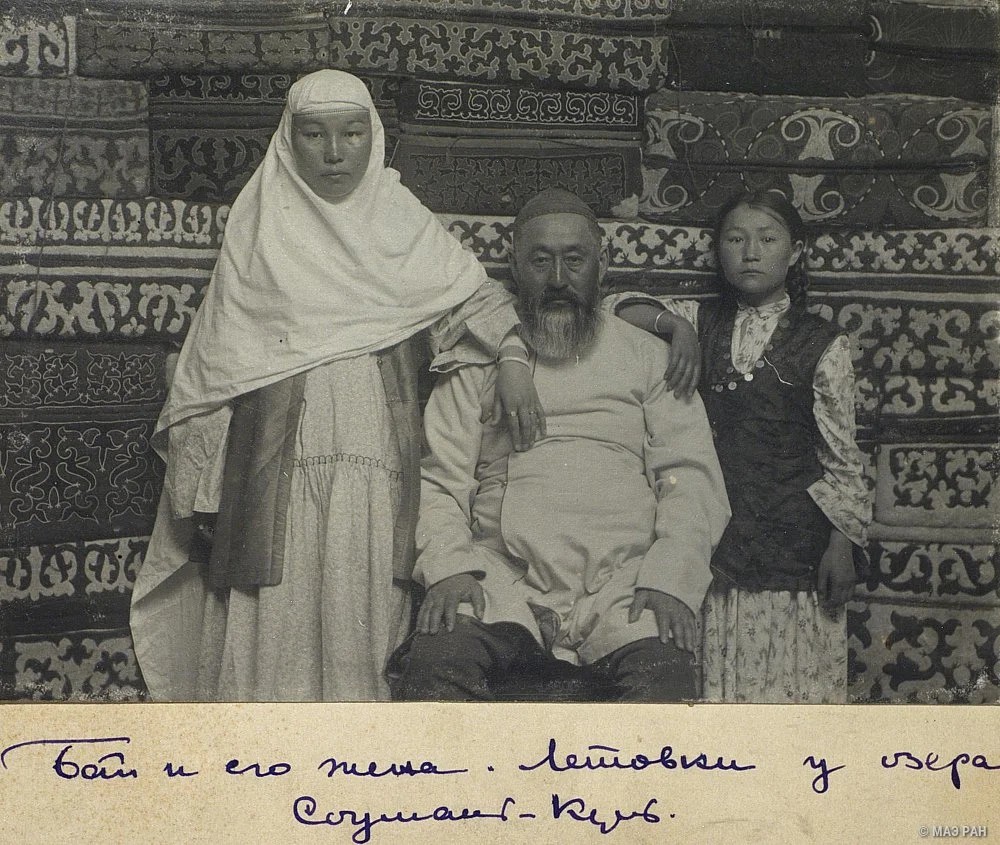

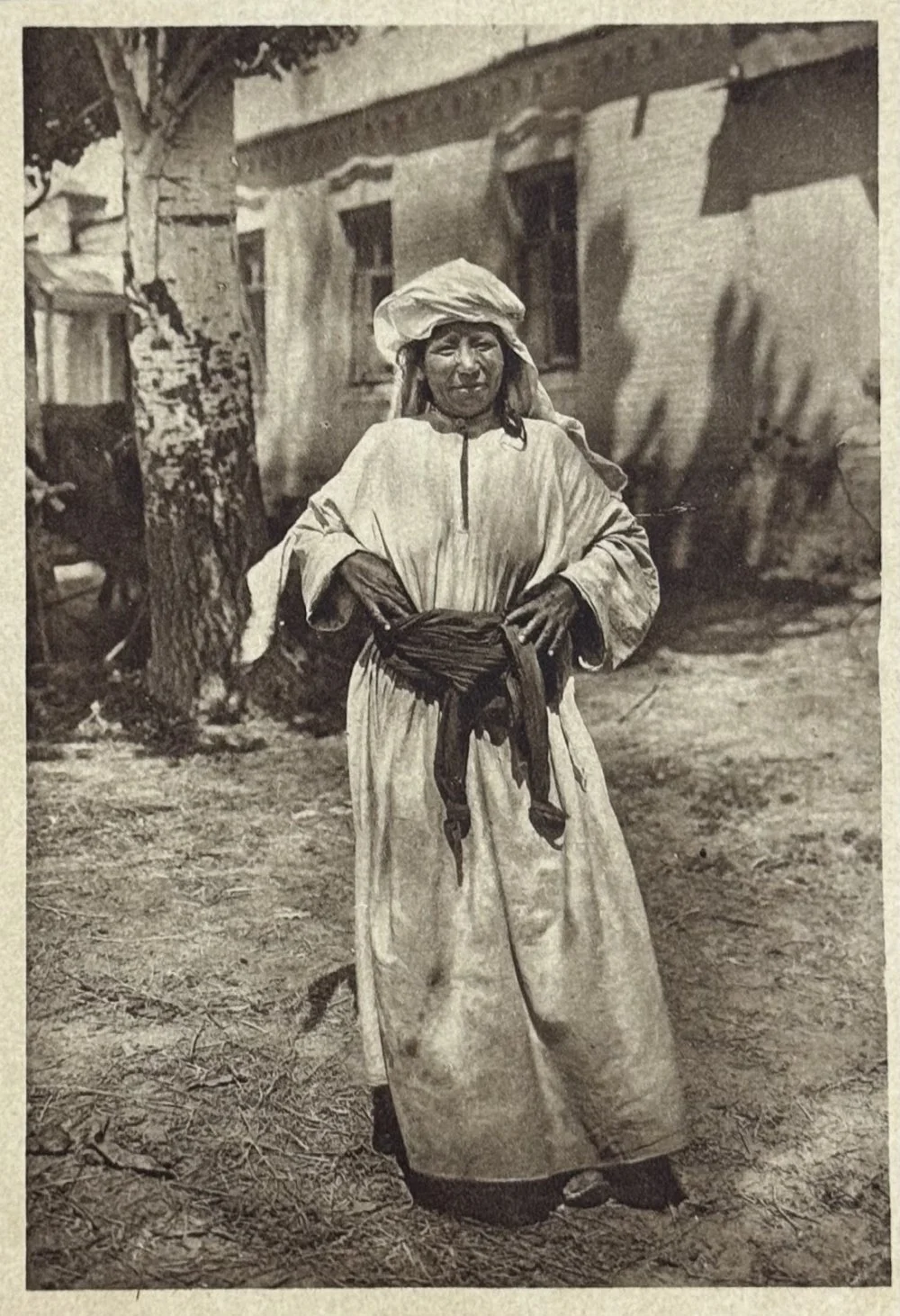

Samuil Dudin. 1899. Photograph from the album «Kazakhs of the Semipalatinsk Region» / romanovempire

When Russian ethnographer and traveler Samuil Dudin's photographs of Central Asia were unveiled at the Paris Exposition in 1900, they were a sensation. Today, they are often presented as a moment of international recognition for Kazakh culture. In reality, however, the purpose of Dudin’s expedition, much like similar missions in other empires, was to showcase to the world that the Russian Empire, too, possessed its own ‘exotic natives’.

Samuil Dudin. 1899. Photograph from the album «Kazakhs of the Semipalatinsk Region» / romanovempire

Because Soviet legacies have not been critically examined in depth, we still tend to view the participation of Kazakh performers in the Decades of Art as well as the appearances of Ämre Qashaubaev and Qajymuqan Munaitpasov at the Paris exhibitions as unambiguous cultural achievements. The reality, however, is that the ‘national characteristics’ so vividly displayed at these events ultimately served only to highlight the cultural difference of colonized peoples from their colonizers. More often than not, they functioned as instruments for justifying and reinforcing political domination.

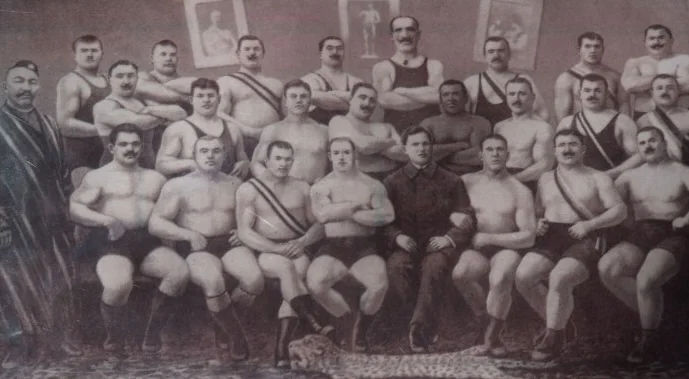

Kazhimukan. On the left in the photo. World championship organized by Mishin in Moscow, 1913 / CSA CFDA RK

In many ways, the Soviet Decades of Art reproduced the aesthetics of colonial exhibitions, albeit in an ideologically reframed format. Alongside the Decades, museums were opened across the country with national costumes on display. Yet, traditional dress, customs, and cultural practices were gradually disappearing from everyday life. By showcasing national culture on stage, in museums, or at exhibitions, Soviet authorities created the illusion of preservation.

In this context, the term 'folklorization' points to the use of folklore for the political purposes of the Soviet state. Baltic and Eastern European historians, including Dima Khaneff and Odette Rudling, have explored these contradictions, showing how Soviet folklorization simultaneously celebrated and hollowed out national cultures.

During the Decades, ethnic distinctiveness was primarily staged through costume—traditional dress was elevated into the central symbol of identity. Thousands of outfits were sewn specifically for these performances, which were often more stylized than authentic. The aim was not to preserve tradition but to showcase each nation in its most flattering form within the Soviet ‘cultural competition of peoples’.

A. Vorotynsky. Scene from the opera “Birzhan and Sara”. Ballet divertissement. Decade of Kazakh Literature and Art in Moscow, 1958. Bolshoi Theatre / CSA CFDA RK

It was during these years that the first Kazakh stage costumes were created, and these garments soon came to represent the ‘national dress’. Historian Francine Hirsch has explored how these newly invented folkloric costumes were promoted across the Soviet Union through museum exhibitions. The focus was placed almost exclusively on festive attire, while everyday clothing was rarely displayed.

This embellished, celebratory national dress was not confined to the Decades: it appeared in cinema, museums, book illustrations, and public cultural events. Over time, these theatricalized costumes became the principal visual symbols to distinguish one Soviet republic from another. Although in-depth research is still limited, a comparison of available photo and film archives suggests a striking conclusion: what is today often seen as traditional Kazakh national clothing in fact largely descends from stage costumes first designed in the Soviet era.

Aisha Galymbayeva. Illustration from the book “Kazakh National Costume” / Bonart.kz

THE STAGE NATIONAL COSTUME AND THE ILLUSION OF TRADITION IN THE USSR

Brightly embroidered dresses and towering headdresses soon came to dominate the visual landscape, eventually becoming accepted as the national costume of the Kazakh people. The Soviet version displaced genuine historical garments, and the originals all but vanished. The costumes presented in Soviet theater and at official events bore little relation to everyday life. They were not reflections of a living tradition but imitations, simulacra that evoked only fragments of a lost national identity. These outfits created the illusion of preserving cultural heritage, while that heritage was actually being rapidly eroded under the homogenizing policies of the Soviet Union.

Shara Zhienkulova. Performance during the Decade of Kazakh Literature and Art in Moscow, 1958 / CSA CFDA RK

In daily life, Soviet citizens were expected to wear a ‘modern’, Europeanized uniform, which is to say, standardized clothing that erased local distinctions. The problem with the stylized national costume was not its mere existence, but the replacement it created. As these staged versions took hold, the authentic garments once worn in everyday life disappeared from use, and the true originals slowly lost both their practical role and their cultural meaning.

Portrait of a wealthy family from Zhetysu. Gradual incorporation of European elements in clothing is noticeable. Kazakhstan, late 19th – early 20th century / From the collection of Azat Akimbek / akimbek.kz

The Soviet project dismantled far more than politics. It disrupted the Kazakhs’ traditional way of life, eroding the skills of felt-making, textile production, and other crafts that had been developed and sustained for centuries. The trade networks of Central Asia collapsed, and with them the material foundations of society. Livestock herding, the backbone of Kazakh culture and economy, was devastated, leaving little room for the continuation of traditional practices.

The scale of the loss was catastrophic. Between 1928 and 1934, Kazakhstan’s livestock population shrank by 97.5 per cent. In 1929, the average household kept 41.6 heads of cattle, but by 1933, that number had fallen to just 2.2 heads.

Drawn into collective farm labor, men could no longer practice traditional or falcon hunting. Women, too, were cut off from felting wool, embroidering syrmaqsi

The Soviet Union, however, presented this rupture as progress, proof that communists had ‘brought order to barren land’. In reality, however, forced industrialization delivered another kind of devastation: as the traditional way of life collapsed, the household economy built on craft and artisanal work collapsed as well.

Like all forms of clothing, Kazakh clothing has always evolved over time. But under Soviet rule, it lost much of its depth and symbolic meaning, and some elements disappeared entirely. The women’s headdress qasabai

What had once been part of everyday life was redefined as spectacle. The Kazakh ‘national costume’ became an object for display, produced in small numbers by artists working with cultural ensembles and designed for stage performances and concert programs. By the 1960s, the qasaba was even placed on a list of ‘unnecessary items’ slated for removal from the collections of the Central Museum of Kazakhstan.

In the end, Kazakh clothing was reduced not to living tradition, but to its Soviet stage version.

Zhelek — a traditional headpiece that just like kasaba gradually fell out of use in national costume . This piece is decorated with circular metal plates, colorful beads, and silk threads. It features a dome-shaped finial made of silver. Kazakhstan, 19th century / From the collection of Azat Akimbek / akimbek.kz

As a result of Soviet cultural policies, decorative ornaments began to be used out of context and lost their original meaning. In traditional Kazakh clothing, every element carried significance—the shape of the kimesheki

The Soviet period, however, sought to erase these intricacies. Artists working for cultural ensembles tried to unify tribal, regional, and age-based variations into generalized ‘national’ images. Countless local styles of kimeshek, once sewn, embroidered, and decorated by women themselves, disappeared. Girls’ headdresses, which changed with each stage of life, also vanished, along with other unique elements that had once served as markers of dynasty or region.

The break in the tradition of sewing and ornamenting clothing led to a distortion of Central Asia’s artistic integrity. Where once ornaments were applied with subtlety, taste, and meaning, in the Soviet period, they were scattered across entire outfits. The contrast between the two eras is starkly visible when comparing Soviet-era stage costumes with photographs of Kazakh clothing from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

THE ‘FRIENDSHIP OF PEOPLES’ AND THE REPRESENTATION OF NATION THROUGH COSTUME

The Soviet state actively promoted bright national costumes through concerts, museums, theaters, and propaganda posters, turning the cultures of different peoples into folkloric images. These stylized outfits appeared frequently in visual campaigns celebrating the ‘Friendship of Peoples’.

The costumes depicted on such posters, postcards, paintings, and other visual products closely mirrored the national costumes actively promoted in Soviet theater and cinema. But they had little in common with the clothing that actually existed before the Soviet era. Strikingly, in these propaganda images, Russian figures were almost always shown in modern, ‘contemporary’ dress, while other ethnic groups appeared in traditional costumes. This visual contrast subtly reinforced the leadership of the ‘Russian people’. Officially, the ideal of the ‘Soviet person' was promoted, but in practice it was most often associated with the Russian image.

TRADITIONAL KAZAKH CLOTHING BEFORE THE USSR: VISUAL SOURCES AND REALITY

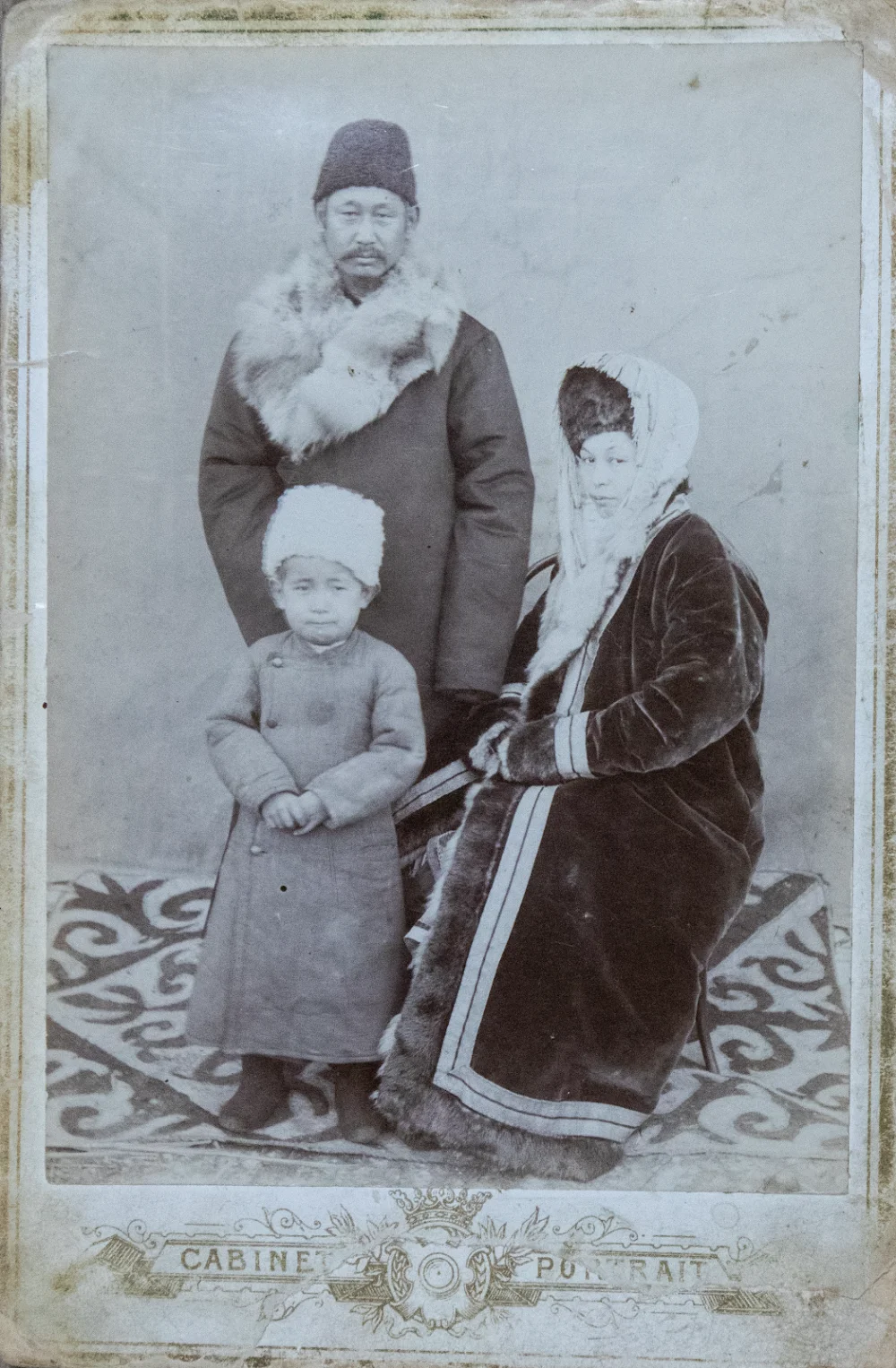

The works of Western and Russian artists and photographers who traveled through the Kazakh steppe in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, despite their orientalist gaze, remain valuable sources for reconstructing the everyday appearance of that time. Consider, for instance, the well-known photographs by Samuil Dudin, taken during his expedition to Jetisu, Akmolinsk, and Semipalatinsk in 1899. In the photo A Bai and His Wife, the clothes of the father, mother, and their young daughter are almost entirely free of ornamentation. By contrast, the trunks and cabinets in the background are richly decorated with patterns.

Compared to Soviet-era costumes, this suggests a striking shift: it is as if the motifs once reserved for household textiles and interior objects migrated onto clothing, losing their original meaning and becoming mere decorative surfaces.

Samuil Dudin. «Bai and his wife». 1899 / romanovempire

In Samuil Dudin’s photographs from 1899—such as The Rich Man, Milking a Mare, Wealthy Woman in a Travel Costume, Girl’s Headdress, Man’s Headdress, Girl in Traditional Dress, Dervish, and Hunter with a Golden Eagle—what stands out is not the abundance of ornamentation, but a very different aesthetic. The clothing is often defined by vertical quilted or stitched lines, a feature also common among other Central Asian peoples.

Thomas Witlam Atkinson. Group of Kazakhs. 1858 / Internet Archive Book Images / Flickr

These lines served both decorative and practical purposes: they reinforced the fabric, gave the garment structure and flexibility, and emphasized its geometric form. This approach to clothing was closer to minimalism and functionality than to excessive decoration. When compared to Soviet-era stage costumes of the mid-twentieth century, the contrast becomes striking: where turn-of-the-century garments used embroidery and ornament sparingly, Soviet designs covered entire outfits with bold, exaggerated patterns.

In Stalin’s Soviet Union, the national costume was expected to function as a clear visual marker to distinguish one nation from another. Folklore, too, was mobilized not simply to represent but to classify and draw rigid boundaries between peoples. Yet, from a scholarly perspective, such boundaries are inherently abstract. Communities sharing the same region inevitably interact, and no culture can remain ‘pure’ or untouched by outside influences—every culture is, by nature, hybrid. The Bolsheviks, rooted in their materialist worldview, chose to ignore this reality.

THE KAZAKH FILM-CONCERT: STAGE COSTUME AND THE FOLKLORIZATION OF CINEMA

The same logic shaped the national costumes showcased during the 1936 Decade of Kazakh Art in Moscow, later immortalized in the 1943 kinokontsert (film-concert) Pod zvuki dombry (Dombyra üni (in Kazakh)/To the Sound of the Dombyra). The film was produced by the Tsentral’naia Obedinennaia Kinostudiia, or the Central United Film Studio, (abbreviated as TsOKS), directed by Adolf Minkin and Sergei Timoshenko, with the script initially written by Kabys Siranov, deputy director of the studio.

The film featured leading Kazakh performers of the era: Dina Nurpeisova, Kulyash Baiseitova, Qanabek Baiseitov, Ali Kurmanov, Shara Jienqulova, and Jamal Omarova. During wartime, kinokontserts were considered an efficient and accessible way to satisfy the public’s appetite for cinema. They boosted soldiers’ morale at the front while continuing the larger pre-war project of folklorization.

The genre of the kinokontsert perfectly embodied the Soviet cultural formula—national in form, socialist in content—serving as a state-sanctioned representation of ‘traditional’ culture. In Pod zvuki dombry, Kazakh culture was presented in a highly folklorized form: national costumes, music, and dance became its central features, while contemporary motifs were pushed to the margins. What is particularly striking is that during the war years, the Soviet state actively drew on the tradition of the Kazakh heroic epic to raise soldiers’ morale by invoking images of historical figures who had resisted Russian colonialism, such as Kenesary, Syrym, and Makhambet Ötemisuly.

Archival records reveal that the film initially included plans to celebrate national heroes like Syrym, Isatai Taimanuly and Makhambet Ötemisuly, but these scenes were ultimately rejected. The contributions of Kazakh soldiers to the defense of the Soviet Union were similarly downplayed: for instance, episodes from the opera Forward, Guards! that depicted Kazakh warriors in the defense of Moscow were cut from the final version, ensuring that the spotlight remained firmly on Russian soldiers.

The Kazakh kinokontsert offered a carefully curated vision of Kazakh culture. When viewed as part of the Soviet project of folklorization, the costumes in the film stand out as strikingly different from historical traditional dress. On screen, the outfits appeared far more spectacular than those captured, for example, in Dudin’s 1899 photographs. Yet this theatricality came at a cost: key layers of meaning—regional, social, and age distinctions that once shaped how people actually dressed—were stripped away.

Ivan Panov. Kazakh woman. Photo postcard. Shymkent, first half of the 20th century / Collection of Azat Akimbek / akimbek.kz

For example, the taqiya, a feathered cap traditionally worn by adolescent girls, was reinterpreted in the Soviet era as a symbol of women’s emancipation. In Pod zvuki dombry, it appears on the heads of young women swinging on the altybaqani

The Hujum campaign—a Soviet initiative first launched in Uzbekistan in 1927 to promote gender equality by abolishing the paranja (veil)—met with widespread resistance and had largely subsided by 1929. Nevertheless, in Soviet visual culture, Uzbek and Tajik women continued to be depicted without the veil, often in taqiyas, which came to symbolize gender equality. Thus, the notion of a national costume in the Soviet era came to be more closely aligned with ideology than with historical accuracy. For instance, on Friendship of Peoples propaganda posters, Uzbek women were never shown in paranjas, nor Kazakh women in kimesheks.

Veil-burning ceremony in Andijan on International Women’s Day, 8 March 1927 / Great Soviet Encyclopedia / Wikimedia Commons

In short, the Kazakh kinokontsert became a vivid example of folklorization in Soviet cultural policy. Similar kinokontserts were filmed in Uzbekistan (in 1941 and 1943) and Tajikistan (in 1945), and in 1944 a joint concert of the five Central Asian republics was released. These films visually and musically folklorized Central Asia, presenting ‘national culture’ through a distinctly Soviet orientalist lens. Historian Michael Smith observes:

‘During the Second World War, the most memorable image of the Soviet Muslim peoples was the scenes in which they sing and dance in a series of kinoconcerts; these films were meant to entertain soldiers at the front, offering them an exoticized image of the eastern peoples.’

DECOLONIZING CULTURE AND RETHINKING THE SOVIET LEGACY

Folklorization was at once a tool of preservation and a mechanism of control. It transformed Kazakh culture into fixed, limited, and immutable national symbols with stylized content. In the first three decades of Kazakhstan’s existence as an independent state, the costumes shown at mass celebrations largely followed the tradition of Soviet-era stage national dress. As a result, public perception formed that national clothing belonged only in Nauryz festivities or theatrical performances and had little relevance in everyday life.

This is precisely why recent efforts by individual designers to create everyday garments in an ethnic style can also be seen as a decolonial practice. Yet, as experience shows, it is difficult to completely abandon the Soviet legacy of folklorization: most often, what emerges is a hybrid product—a modern cut, elements of historical everyday clothing, and the stylization of the Soviet stage costume. Still, the more contemporary the form and silhouette are, the further such clothing moves from the Soviet experience and the closer it comes to the functionality of historical Kazakh clothes.

Kazakh woman spinning wool, Kazakh ethnographical village Aul Gunny, Talgar city, Almaty, Kazakhstan / Alamy

Although more than three decades have passed since the collapse of the USSR, and many post-Soviet countries are actively engaged in rethinking their past, the notions of nationhood shaped during the Soviet era continue to exert a strong influence. In the Central Asian republics, for example, national identity is still often described through the lens of national costumes that were created or standardized in Soviet times.

Soviet ideas of national identity became so firmly entrenched in culture that today they are often perceived as self-evident. On holidays inherited from the Soviet Union, such as Kazakhstan’s Day of Unity of the People, it has become customary to showcase representatives of different ethnic groups in ‘national costumes’ performing ‘national dances’. Indeed, official media and television broadcasts remain saturated with such imagery.

The Soviet legacy thus persists behind a façade, where national clothing is presented as an allegedly authentic ethnic marker. But when we dress ourselves and others in these folkloric forms, we must ask: Through whose eyes are we seeing this identity?

Indeed, what is at stake is not simply the accuracy of historical garments but the way we imagine ourselves as communities and nations. To inherit a culture is not to freeze it in decorative patterns or stage costumes but to enable its creativity and individuality to constantly evolve. The challenge lies in making the difference between heritage as spectacle and heritage as practice, in reclaiming traditions as living knowledge rather than Soviet-era imitations. Only then can Kazakh clothing, art, and craft once again embody a genuine expression of self.