Jülüs Ceremony of Sultan Osman II. February 26, 1618. Topkapı Palace Museum, Istanbul/Wikimedia Commons

On the evening of 20 January 2025, the inauguration ceremony of Donald Trump took place in the Rotunda of the Capitol in Washington, marking his official assumption of office as the 47th President of the United States. Inspired by this moment, let’s take a step back in time to explore how leaders of great empires—and Kazakh khans in particular—ascended to their thrones and examine the fascinating rituals and customs that defined their journeys to power.

Coronations of Byzantine Emperors

The coronation ceremony of Byzantine emperors was meticulously detailed, with every gesture, every move made by the ruler, and every aspect of their attire holding special symbolic meaning. This ceremony was among the most lavish of its time and significantly influenced coronation practices in many other states. The very word ‘inauguration’ is derived from the Greek term Ἀναγόρευσις (meaning ‘proclamation’).

Court of Emperor Justinian with Archbishop Maximian of Ravenna and three other clerics on Justinian's left, and two court officials and his guards on his right. Apse mosaic. Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna, Emilia-Romagna, Italia. 6th century/Wikimedia Commons

The nature of the ceremony reflected the Byzantine perspective on monarchical power, which was seen as being derived from the people and God simultaneously. Accordingly, parts of the emperor’s coronation involved the approval of members of various social strata, while others centered on the patriarch placing the crown upon the heads of the emperor and his consort.

The ceremony began in the Great Imperial Palace of Constantinople, with the emperor preparing for day one of the palace’s richly adorned chambers. A key part of the process was the donning of luxurious garments and regalia, including the purple mantle and the crown. In different periods (primarily before the seventh century), when the military wielded greater influence over the monarchy, the emperor would be lifted on a shield as part of the coronation ritual. Then the emperor, accompanied by high-ranking officials, the patriarch, and military commanders, proceeded to the Hagia Sophia, where representatives of various societal strata gathered, including senators, clergy, and soldiers.

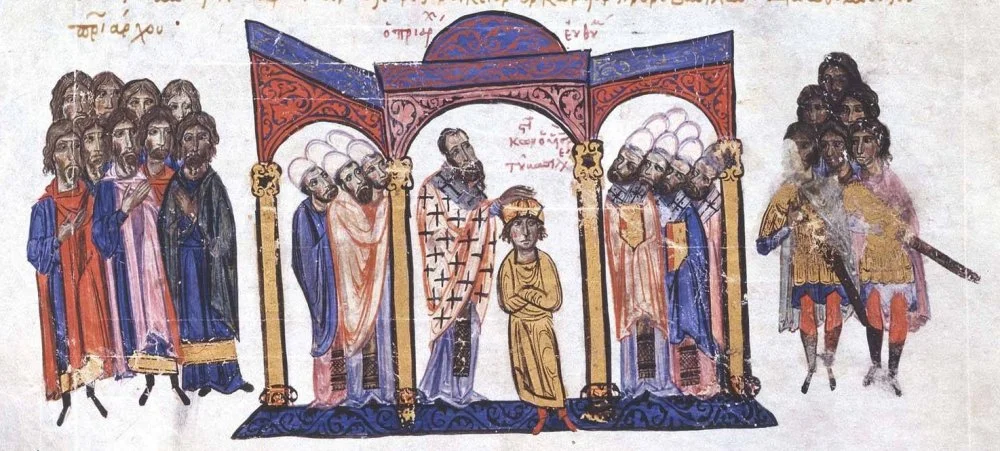

Coronation of Constantine VII as co-emperor in 908/Wikimedia Commons

The emperor entered the cathedral accompanied by hymns and acclamations. At the central moment of the service, the patriarch placed the crown on the emperor's head and that of his consort, symbolizing divine blessings upon their reign. The emperor offered prayers and swore an oath on the Gospel, pledging to rule justly and to protect the Orthodox faith.

Chronicle by John Skylitzes, which depicts the elevation of the emperor on a shield by the soldiers. National Library of Spain/Wikimedia Commons

After the religious part of the ceremony was over, the emperor ascended a special platform at the Hippodrome, where he was presented to the people, who greeted him with cries of ‘Axios!’ (meaning ‘He is worthy!’). Following the enthronement, feasts, spectacles, and games took place in celebration.

The Election of the Great Khan of the Mongol Empire at the Kurultai

In his renowned work Jami' al-Tawarikh (The Compendium of Chronicles), the famous Persian historian and statesman Rashid al-Din (1247–1318) provided a detailed description of the coronation ceremonies of the Mongol khans. Commissioned by Ghazan Khan to compile an extensive chronicle of the Mongol Empire, al-Din had access to Mongol sources, archival documents, and direct communication with Mongol officials and military leaders.

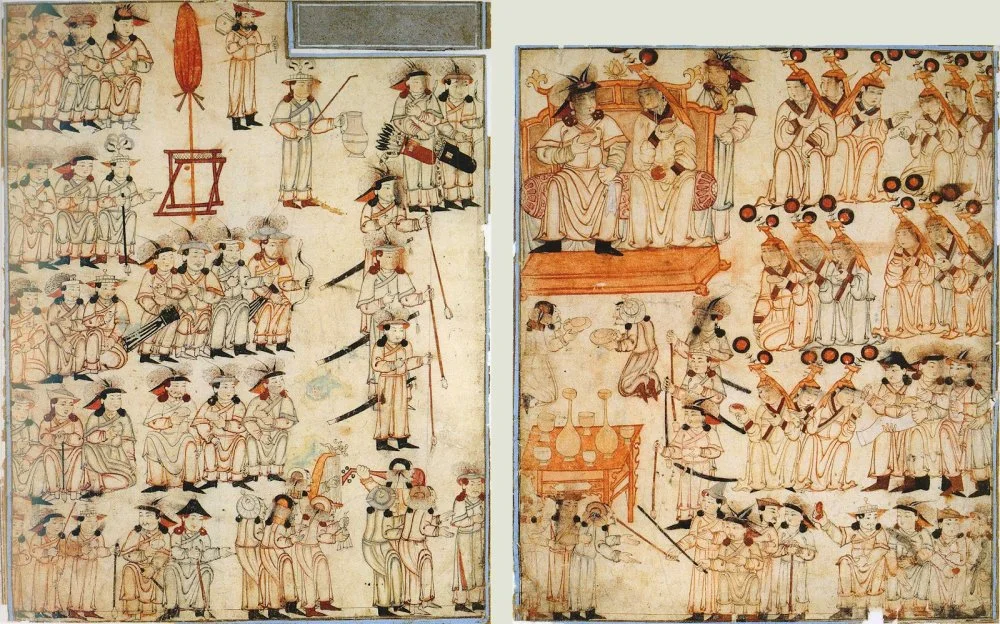

Temüjin proclaimed as Genghis Khan in 1206. Jami al-tawarikh manuscript/Wikimedia Commons

According to the traditions of the Mongol Empire, the election of the Khagan (Great Khan) required convening a ‘Great Kurultai’i

Following the announcement of Möngke’s election, astrologers and soothsayers were immediately tasked with seeking a favorable celestial omen. As if on cue, the sun emerged from behind clouds after several overcast days, a moment that was immediately interpreted as a sign of divine approval. As a gesture of respect for supreme authority, all attendees removed their headgear and placed their belts over their shoulders.

Enthronization of Genghis khan. Left part of a double-page illustration of Rashid-ad-Din's Gami' at-tawarih. Tabriz, 1st quarter of14th century. Staatsbibliothek Berlin, Orientabteilung, Diez A fol. 70, p. 20/Wikimedia Commons

The coronation ceremony of Möngke Khan took place in Karakorum, the capital of the Mongol Empire. All attendees—descendants of Chinggis Khan, rulers, military commanders, and soldiers—knelt before him nine times as a gesture of respect and allegiance. The khan himself sat upon a throne inside a yurt adorned with gold-embroidered silks. To his right were seated princes, the highest-ranking of whom faced him directly, while to his left were his wives.

On the same day, Möngke Khan issued a decree to maintain harmony on this auspicious day, forbidding disputes or quarrels. He also declared that domestic animals should not be burdened with heavy loads and their blood not be spilled. The feast in honor of the new Great Khan lasted an entire week, and each day, 2,000 carts of wine and kumis were consumed along with 300 horses and cattle and 3,000 sheep. This grand celebration underscored the wealth and unity of the Mongol Empire under its new leader.

The ‘Girding with the Sword’ Ceremony for Ottoman Sultans

Unlike the Great Khans of the Mongol Empire, Ottoman sultans were not elected at tribal assemblies, nor did they have an official tradition of appointing a crown prince. The ascension of a şehzade (prince) to the Ottoman throne following the death of a sultan—or, in rare cases, an abdication—was often fraught with danger and sometimes marked by bloodshed. It was crucial for the prince to reach the capital before his brothers and rivals and, after assuming authority, to execute them to secure his position. However, the most decisive factor in securing power and survival was the favor of the Janissaries.

Beyazit proclaimed sultan. 15 century miniature/Wikimedia Commons

During the peak of the Ottoman Empire, the Janissaries played a key role in the coronation of sultans, even though the sultans did not wear crowns. The culmination of the enthronement ceremony, known as Cülûs, was the Kılıç kuşanma, meaning ‘girding with the sword’. As part of this ritual, the newly inaugurated sultan took a special Janissary oath, invoking Ali, Hacı Bektaş-ı Veli, and the sword itself. The oath began with these words:

‘My head is uncovered, my soul is void, the sword reddens with blood. On this path, so many heads shall fall, yet no one shall pay heed’.

To prevent palace intrigues, the news of the death of the sultan was kept in the strictest secrecy, and it was not uncommon for viziers and the chief mufti to be summoned for an ‘urgent meeting’ with the sultan only to be greeted by the new sultan instead. Thus, the funeral of the old sultan took place only after the coronation of the new ruler. Following the girding with the sword, it was customary for the new sultan to visit the tomb of Abu Ayyub al-Ansari, a companion of the Prophet Muhammad who participated in the siege of Constantinople in the seventh century.

The Coronation of the Padishah of the Mughal Empire

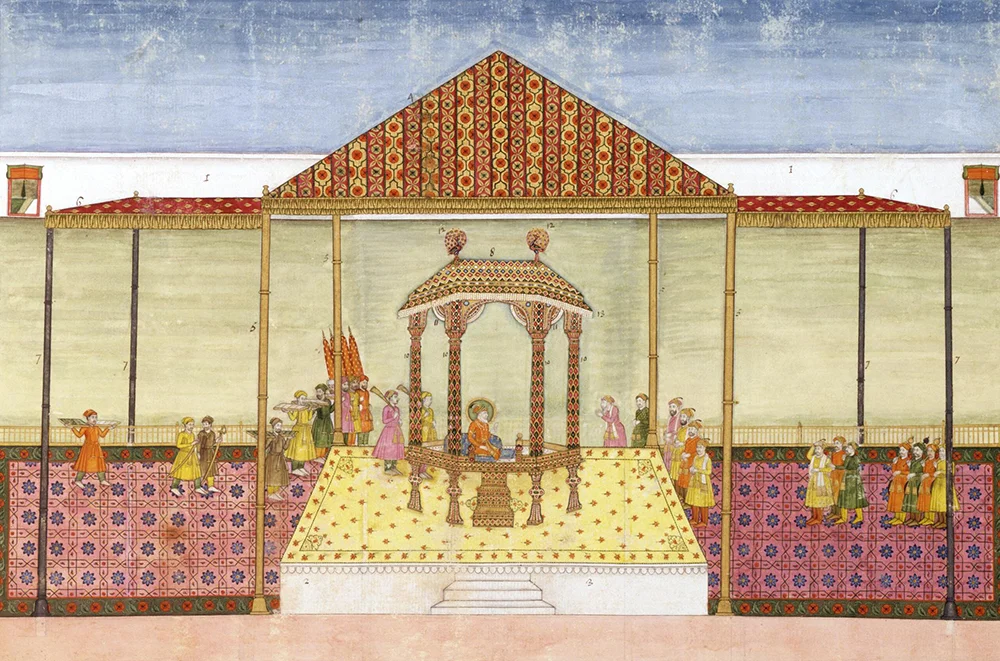

Unlike the warlike Ottomans, the coronation of the padishahs of the Mughal Empire placed significant emphasis on astrology, both Islamic and Hindu. Traditionally, Mughal emperors were crowned on the first day of Nowruz. However, this tradition did not apply to the extravagant Shah Jahan (his title literally meaning the ‘lord of the world’), the creator of the enchanting Taj Mahal and the legendary Peacock Throne.

In his case, astrologers not only spent considerable time calculating the most auspicious day, carefully looking at celestial alignments, but they also declared the month in which the coronation took place, according to the Islamic calendar, as the official start of his reign. Moreover, Shah Jahan had not one but two coronations—the first in February and the second in August as astrologers had determined that no more favorable days for such an event would come that year. Nevertheless, during his second coronation, Shah Jahan distributed real positions and wealth to his subjects, while he received authentic and precious gemstones as gifts.

The Mughal Emperor and His Court. c. 1774/Wikimedia Commons

The tradition of a double coronation was continued by Shah Jahan's son, Aurangzeb, known as Alamgir (meaning ‘conqueror of the universe’).

Attributed to Abu al-Hasan. Shah Jahangir. 1617/Wikimedia Commons

Aurangzeb believed that his first coronation lacked sufficient grandeur due to the ongoing power struggle with his brothers. Court astrologers selected an auspicious day for a second coronation in May 1659. Aurangzeb ceremonially walked through the Diwan-i-Aam (the Hall of Public Audience), adorned with forty columns, in the Red Fort of Agra and ascended his father’s golden Peacock Throne, fully encrusted with unique precious stones. The celebrations and feasting lasted an impressive two months.

Abu'l Hasan. Celebrations at the accession of Jahangir. Jahangirnama. Mughal court at Ajmer or Agra, ca. 1615-18, Institute of Oriental Studies, St. Petersburg/Wikimedia Commons

The Elevation of Kazakh Khans on the White Felt

According to ancient Turkic-Mongol traditions of succession, the khan's title among the Kazakhs was not directly hereditary. Similar to the Great Khans of the Mongol Empire, a candidate for the throne had to undergo an official election (Han sailau) at a kurultai of the Kazakh nobility. Naturally, Kazakh khans were chosen exclusively from the Chinggisid lineage through the paternal line, though the most legitimate candidates were those who also descended from the Törei

Lifting up the Khan on a white felt/From the open sources

After a khan was elected at the kurultai, a formal proclamation followed with a solemn ritual of his elevation on white felt (Han köteru), symbolizing the purity of his political intentions. This ceremony was typically held on a Friday. In Kazakh etiquette, Chinggisid sultans held a special, privileged status, and strict rules governed interactions between them and commoners. The white felt in this hierarchy played a significant role, representing the ‘white bone’, a metaphor for nobility.

The honor of lifting the khan on the white felt was reserved for the most influential sultans, beys, batyrs, and tribal leaders. The khan was dressed in ceremonial attire, and his livestock was distributed among those present. He was then lifted three times while the assembly shouted in unison, ‘Khan! Khan! Khan!’ After the ceremony, the felt was cut into small pieces, which the guests took home as mementos of the occasion.