This is the story of an incident that occurred in the early 1630s, in a time when the provinces of the Netherlands, then encompassing both Belgium and Luxembourg, were deeply involved in the bloody Thirty Years' War while also continuing their struggle in the Eighty Years' War for independence from Spanish rule. One prosperous merchant, enthused by the news of a precious shipment arriving from the eastern Mediterranean, showed his gratitude and generosity by rewarding the sailor who brought him these good tidings with a smoked herring. The sailor, deeming it improper to consume only one herring, seized an onion from on a table in one of the many opulent rooms of the merchant's house and used it to complete his meal.

To his misfortune, and to the detriment of the merchant and his entire trading establishment, the somewhat unappetizing onion turned out to be the bulb of the highly prized tulip known as Semper Augustus (in Latin ‘Forever August’), named in honor of the first Roman emperor. The financial losses incurred due to this hasty repast equaled the annual expenditure for maintaining the entire crew of the ship to which the sailor belonged. Predictably, he was incarcerated for committing a grave criminal act, and there is no information available regarding his subsequent fate. Alexander Dumas aptly remarked in his novel The Black Tulip that ‘to kill a tulip is an appalling crime in the eyes of a genuine gardener. To kill a person—is less appalling.’

Jacob Marrel. Two tulips, a seashell and an insect. 1634 / Wikimedia Commons

This story was recounted in 1841 by the renowned Scottish writer and journalist Charles Mackay, the author of the book Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. It contains a dedicated chapter to ‘tulipomania’, which coincided with a period in Dutch history known as the ‘Golden Age of the Netherlands’ that was marked by flourishing achievements in trade, science, and art. However, it's worth noting that during this prosperous century, the bulbs of this innocent flower often surpassed the value of noble metals since they sometimes cost more than gold, weight for weight.

This isn't just a hypothetical literary comparison, as tulip bulbs were sold by weight at the time, and specific, small weighing measures were used for this purpose. To avoid the complexity of converting seventeenth-century Dutch guilders, sometimes called florins, into Euros, dollars, or tenge, and accounting for inflation, let's once again refer to Charles Mackay.

At that time, when a price of 5,500 guilders for a small Semper Augustus bulb—the same one our sailor munched on—was considered a successful and economical deal, you could purchase four tons of wheat, eight tons of rye, four large oxen, four fat pigs, twelve large sheep, 500 liters of wine, 4,000 liters of beer, two tons of butter, half a ton of excellent Dutch cheese, a bed with all available comforts, a complete set of clothing of that era, and, for some reason, a silver drinking cup—all together. It's essential to note that this refers to the collective purchase, not individual items. Considering that we may have made a slight error in translating the complex and variable liquid measures of that time into measurements we are familiar with, even just 4,000 liters of beer and half a ton of cheese added to the deal would already seem like the deal of a lifetime.

Tulips on tiles of Istanbul mosque / Alamy

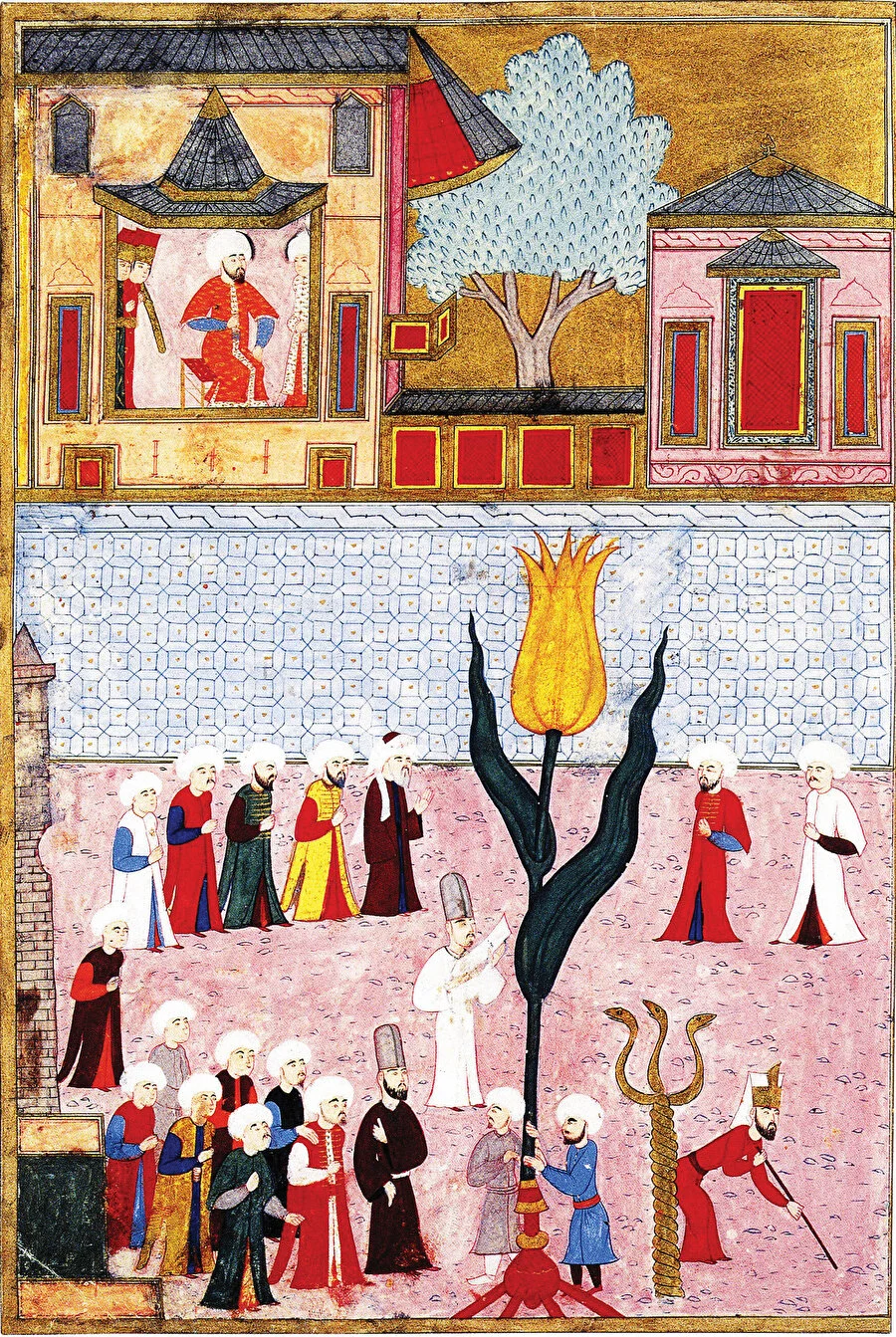

Surprisingly, the Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent plays a role in this story too. In 1554, a twenty-two-year-old Flemish man named Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq was sent as an envoy to the court of the venerable, and undoubtedly greatest, of Turkish rulers. It should be noted that de Busbecq was a herbalist and a botanist who studied the use of plants for medicinal purposes.

Unfortunately, the Habsburg dynasty, which ruled Austria, was engaged in the ongoing Austro-Turkish wars at the time, and Suleiman had not yet abandoned the idea of capturing Vienna. This trip proved to be fateful, especially for the Netherlands, which partially included his native Flanders. It seemed that the ambassador of the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I was more excited about the variety of beautiful flowers and the immense Ottoman interest in them than about meeting the great sultan or the importance of state affairs.

In his memoirs, known as The Turkish Letters, de Busbecq wrote that the Turks did not consider it extravagant to purchase a bouquet of their favorite flowers. As we will learn later, the Dutch would also not consider it extravagant to pay 5,500 guilders for a yet-to-bloom tulip bulb. In any case, Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq became the man who introduced Western Europe to the tulip and the lilac as well.

Claude Monet. Tulip field in Holland. 1886 / Wikimedia Commons

‘As we strolled through the area, we encountered a multitude of flowers—narcissus, hyacinths, and what the Turks referred to as tulips. We were astonished that they were blooming in the middle of winter, not the most favorable season,’ noted de Busbecq in his diary. Naturally, the Turks didn't call them ‘tulips’, and they were known as ‘lâle’ in Persian (in Turkish ‘lâle’), while ‘tulip’ (in Turkish ‘tülbent’), also borrowed from Persian, referred to a fine, costly patterned fabric or a headscarf made from this material, something we commonly refer to as a ‘turban’. De Busbecq evidently got something mixed up there, either pointing in the wrong direction or indicating a tulip pattern on a turban. Nevertheless, he took this beautiful flower with him, albeit with a comical name.

Meanwhile, the tulip had always been one of the most widespread and coveted patterns in the Ottoman Empire and across the Muslim world. In fact, hardly anyone in the country, regardless of their status, remained untouched by its aesthetic charm. The Tulip Era (in Turkish ‘Lâle Devri’) was named in the flower’s honor, marking the most peaceful period in the Ottoman Empire's history (1718–30). The traditional Turkish music scale, as well as romantic expressions in Ottoman poetry, were influenced by tulips. These flowers were used to embellish everything from tombstones and expensive İznik porcelain to women's kaftans and manuscripts of the Koran. Even the mighty Sultan Mehmed II, the conqueror of Constantinople, couldn't escape the allure of the tulip and, under the humble pseudonym ‘Avni' (in Turkish ‘helper’), penned verses dedicated to this flower: ‘Winebearer, pour me wine, for one fine day, I will lose the tulip garden.’ It's thus no wonder the tulip became a symbol of both the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic.

Hendrik Gerritsz Pot. Flora's wagon of fools. 1637-1638 / Alamy

'Tulip mania', with its mercantilism and speculative bubble, is undoubtedly a later Western European story because it was already known in the East—in Central Asia, Iran, and Anatolia. With the rise of the Ottoman Empire, the aesthetics of the tulip spread even further. Notably, in almost all European territories under Ottoman rule—from the Greek and Albanian to Serbian and Romanian—the name originates from the Turkish 'lâle' rather than a distorted form of 'turban'. In countries strongly influenced by Persian culture and language, the same word is used, such as in Azerbaijani, Turkmen, Uzbek, Uyghur, Urdu, and Hindi. However, the tulip remained a universally accessible source of inspiration and a metaphor for beauty, something ethereal.

Almost 450 years before de Busbecq's trip to Istanbul, Omar Khayyam celebrated the beauty of the tulip bloom with the words: ‘You have taken your purple color from the tulip.’ Sufi poets also extolled the virtues of tulips, including Saadi, Rumi, Hafiz, and Navoi, since in both the Persian and Ottoman script, 'lâle' is an anagram of the word 'Allah'.

However, in Kazakh, it is neither a 'tulip' nor 'lâle' but 'қызғалдақ' (in Kazakh ‘red flower’). This is echoed by the verses of the founder of the Mughal Empire, Babur: ‘Sometimes tulips paint the boundless steppe the color of roses’, although the Persian 'lâle' also derives from the root meaning 'red'. Common claims about Kazakhstan being one of the possible homelands of tulips also add to the flower's allure. From possibly the most famous tulip researcher Zinaida Botschantzeva's book Tulips: Morphology, Cytology, and Biology (1962), we learn that scientists have been asserting, since the 1930s, that Central Asia ranks first in terms of the number of tulip species, making it the home of tulips. Consequently, cultivated tulips have their origins in the wild tulips of Central Asia: the Pamirs, the Hindu Kush, and the steppes of Kazakhstan.

The merchant and tulip addict. Caricature painting from the mid-17th century / Musée des beaux-arts de Rennes.

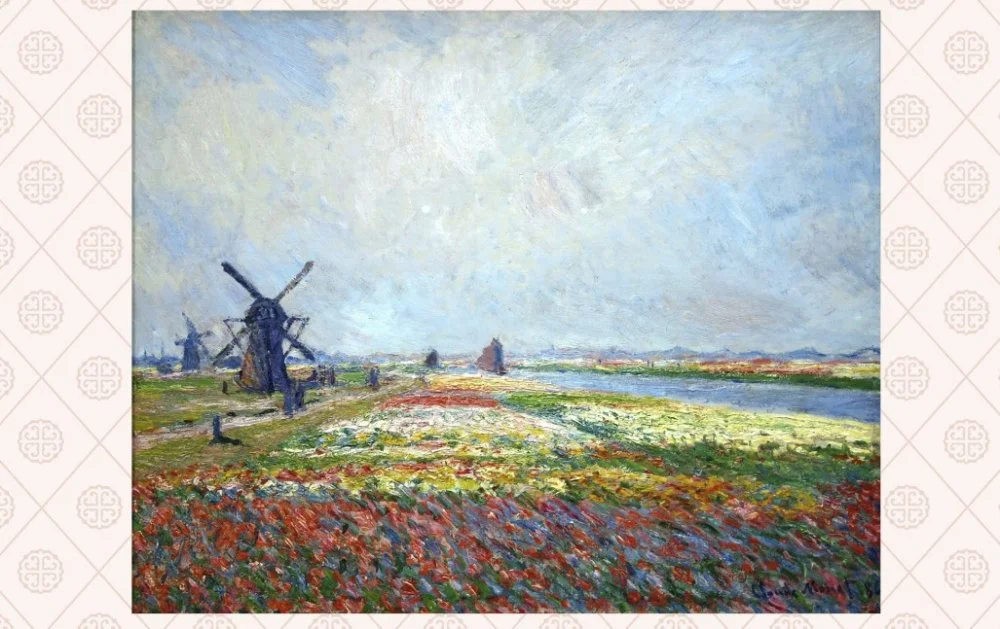

Meanwhile, the tulip bubble, driven by a surge in demand, speculation, and futures trading that attracted investors from various social backgrounds, burst in 1637. Tulip prices plummeted rapidly, leaving those who had committed to purchasing tulips at vastly inflated prices teetering on the brink of financial ruin. Simultaneously, global literature gained one of its most striking stories of madness, greed, and despair, partially chronicled by Charles Mackay. While it is now commonly believed that tulip fever and its subsequent financial collapse did not have such a devastating impact on society and the economy, the epithet ‘Land of Tulips’ has remained attached to the Netherlands. Nevertheless, today, the Netherlands, which annually produces nearly three billion tulip bulbs, accounts for 81 per cent of the world's tulip exports—including to the birthplace of tulips.

Jacob Marrel. Tulips. 1645 / Wikimedia Commons

What to read

1. de Busbecq, Ogier Ghiselin (1968). The Turkish Letters of Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, Imperial Ambassador at Constantinople, 1554-1562. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

2. Goldgar, Anne (2007). Tulipmania. Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

3. MacKay, Charles (1841). Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions. Vol. 1. London: Richard Bentley.

4. Bochanceva, Z. P. (1962). Tulips. Morphology, Cytology, and Biology. Tashkent: Academy of Sciences of the Uzbek SSR Publishing House.