The era of the Ulus of Jochi, more widely known as the Golden Horde, founded by Chinggis Khan’s eldest son, stands as one of the most enigmatic and formative chapters in the history of Kazakhstan. Until recently, how it first developed and its later evolution and existence were examined in an unfairly shallow manner, leaving more questions than providing any real answers. In this interview with Qalam Global, Professor Yerkin Abil, Doctor of Historical Sciences, reflects on how people lived in what was once the most influential power on the Eurasian steppe.

What Does the Term Orda Mean?

The name ‘Golden Horde’ appeared in the sixteenth century, only after the dissolution of the state. In written sources, the terms ‘Aq-Orda’ and ‘Kök-Orda’ were used with varying meaningsi

In modern Kazakh, orda means 'center' or 'capital'.

Erkin Abil / Qalam

It could refer not only to an administrative center, but also to the location where, along with the ruler, merchants, artisans, and others would settle temporarily. One hypothesis suggests that the name may have been linked to the golden decoration of the khans’ tents, such as those of Batu Khan and Uzbek Khan. Later, the term was consolidated in Western sources as the Golden Horde. Aq-Orda originally meant 'the Great Orda' or 'the Main Orda' and initially referred to the eastern seat of power, located in the territory of present-day Kazakhstan.

The Economy of the Golden Horde

The basis of the Horde’s economy was livestock herding. However, by this time, most of the population had shifted from a purely nomadic lifestyle to semi-nomadic farming, and trade remained the primary source of state revenue. Livestock was taxed at just 1 per cent of the herd, while trade was initially taxed at 10 per cent before being reduced to 3 per cent of the turnover. Importantly, this 3 per cent served as the primary source of treasury income.

One of the significant innovations made by the Golden Horde was the abolition of internal customs barriers. Trade routes from Crimea to China were open to caravans without obstruction, stimulating rapid commercial expansion and strengthening the state’s economy through the uniform 3 per cent tax. Merchants were issued a special document known as the tañbai

The Golden Horde: Paper Money and Insurance

Another innovation made in the steppe was the introduction of paper money. This was not an invention by the Golden Horde itself, but part of the broader practice of the Mongol Empire. However, in this region, the system proved especially effective. For example, in the Ulus of Chagataii

Dang (dirham) of Uzbek Khan. 1345 / monetnik.ru

Under Uzbek Khani

Nomadic Traditions of the Golden Horde Aristocracy

Here’s an intriguing detail: the elite of the Golden Horde spent their summers in Saraishyqi

One of these summer encampments gave rise to the city of Gülstan al-Jadid (or New Gulistan, which meant 'New Rose Garden'), which became a gathering place for merchants and artisans. At times, the orda moved to Saraishyq (meaning ‘Little Sarai’i

Features of the Cities of the Golden Horde

Contrary to popular cinematic stereotypes, the cities of the Golden Horde did not have brick fortresses with high walls in every settlement. Cities had no clear boundaries: they gradually blended into the surrounding suburbs, while the center clustered around madrasas, mosques, bazaars, and palaces.

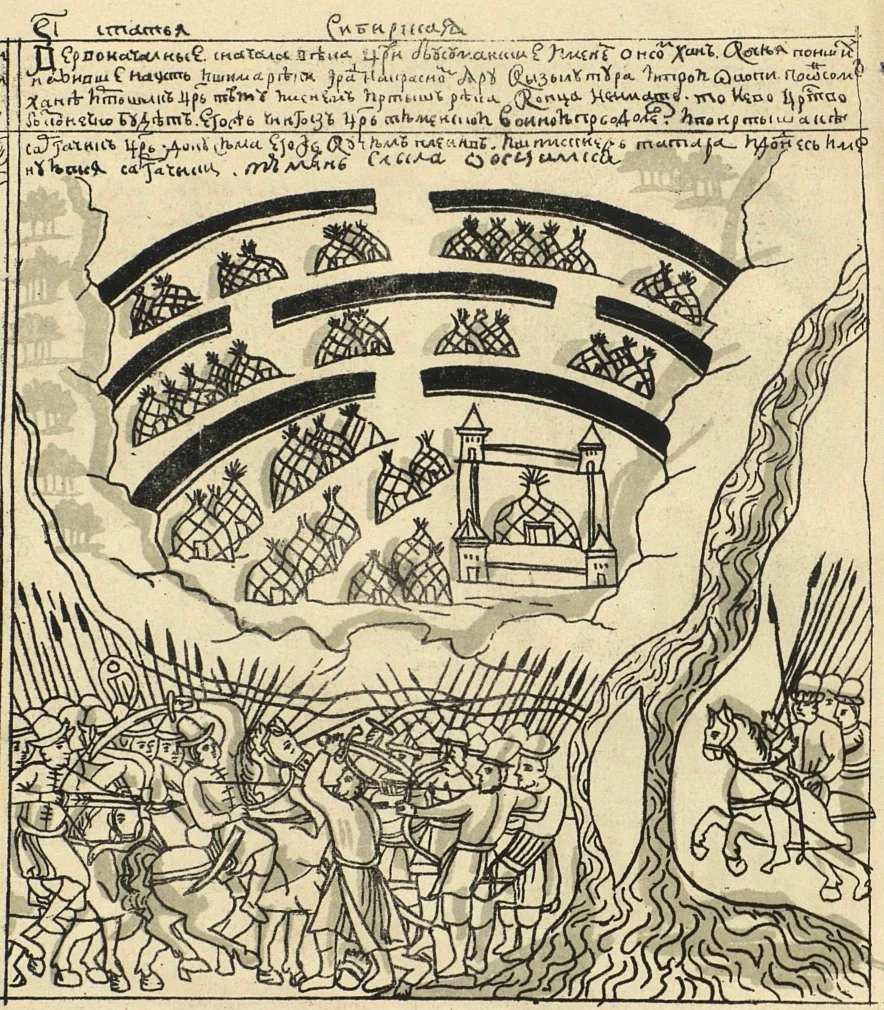

Semyon Remezov. Kyzyltura fortification in The Remezov Letopis / Wikimedia Commons

Fortresses were built only in border settlements. For example, the Siberian city of Qyzyl-Tura on the Irtysh River had three lines of defensive walls, but on the inside were ordinary yurts as it was purely a military outpost—the same applied to Derbent.

The inner areas of unfortified towns are the most difficult to study: without defensive walls, it is challenging for archaeologists to determine the exact boundaries of these communities and to understand where urban development ended and the outskirts began.

Kazakhstan: The Legitimate Heir of the Ulus of Jochi and the Golden Horde?

Why do we put so much emphasis on the role of the Ulus of Jochi? This is because the foundations of modern Kazakh culture were formed from the time of Berke Khani

This period holds a special place in the traditional historical consciousness of the Kazakhs. For example, the legend of Alash Khani

We can confidently say that the roots of the Kazakh people trace back to the Ulus of Jochi, with Khan Kenesaryi

Was Edige, Emir of the Golden Horde, Only a Kazakh Batyr?

Some researchers note that it is incorrect to describe Edigei

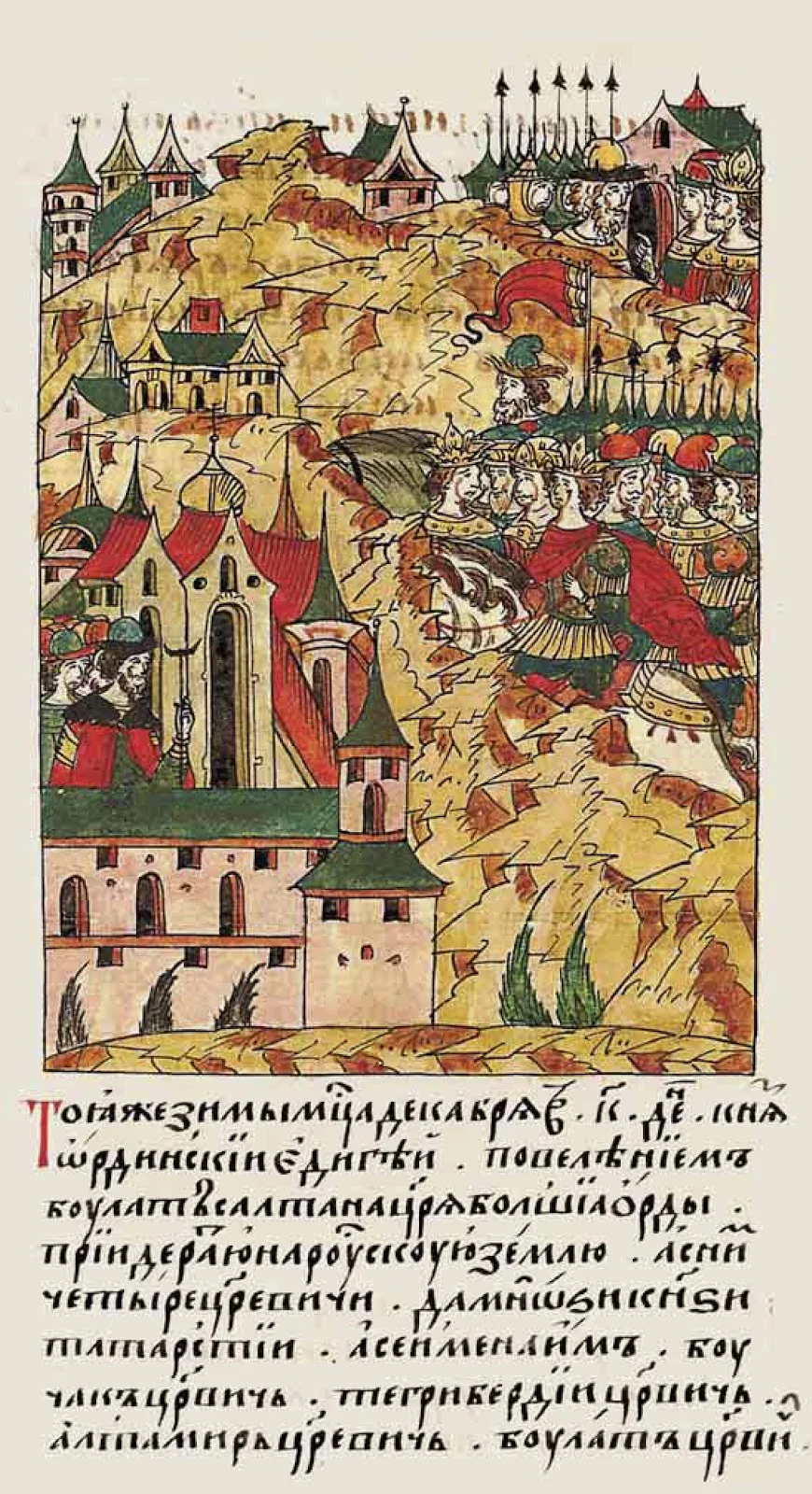

The Invasion of Edigei. Miniature from the Illustrated Vault / Wikimedia Commons

During the Soviet period, each autonomous republic sought to 'create' its own history, which gave rise to the notion that every nation had to have its own singular ‘forefather’. Thus, the Kazakhs were ‘assigned’ the Ak Orda, the Nogais were given the Nogai Hordei

How Is the Concept of Alash Connected to the Golden Horde?

The word qazaqi

In the Golden Horde, qazaq referred to a person who had left their clan, ulus, and ruler, and was now living a free and independent life.

For example, after Muhammad Shaybanii

Monument to the two first Kazakh khans Kerei and Zhanibek. Astana / Alamy

Until the nineteenth century, some sultans would say: 'I am not a qazaq, I am a töre.’ In such cases, they replaced the word qazaq with alash. That is to say, the term alash, which in Turkic traditions meant ‘people’ or ‘tribe’, was used as a collective name for all Kazakh clans and served as a self-designation of the Kazakhs (and at times, more broadly, of Turkic confederations) alongside the ethnonym qazaq. Hence, the expressions alty alash (six alash) and üsh alash (three alash). The word alash also appears in the works of Qadyrgali Jalayir, and it was clearly a political term.

Thus, qazaq was a social term, özbek a cultural-historical one, and alash a political one. Alikhan Bökeykhan applied the word alash not to an ethnicity, but to a nation. Personally, the word alash feels closer to me than Kazakhstani. Alash meant the citizens of the Kazakh Khanate. The word qazaq as an ethnic name became firmly established only between the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries. Gradually, we all began calling each other qazaqs.

This is only part of an interview with Yerkin Abil about the Golden Horde. The full version is available on our YouTube channel Qalam Tarih: