The Venus de Milo statue. Louvre. Paris /Shutterstock

It is no secret that domestic violence is an acute and widespread problem in Kazakhstan. The public outcry after the murder of Saltanat Nukenova by her husband, former Minister of Economy of Kazakhstan Kuandyk Bishimbayev, finally spurred the government into taking some action. The resultant legislation, known as Saltanat's Law and signed by President Tokayev, is, according to Human Rights Watch, a step in the right direction, but it still requires improvements.

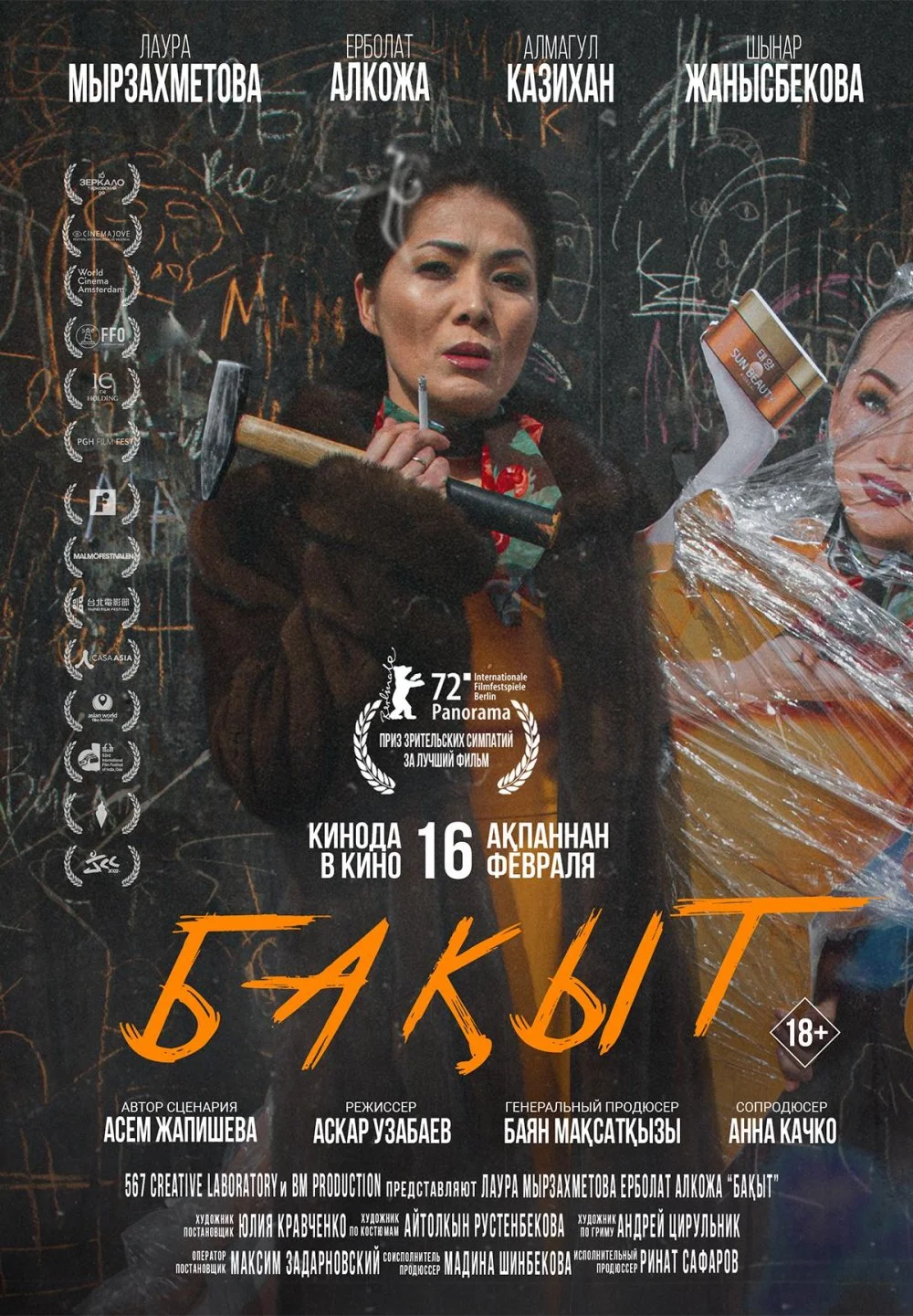

Domestic violence is a regular topic of discussion within the Kazakh cultural space. In 2023, the film Baqyt by Askar Uzabayev and Asem Japisheva attempted to delve into the psychology of this phenomenon and portray it ‘without retouching’ its reality. In autumn 2022, the Kazakh Central State Museum hosted an exhibition called ‘Behind the Door’. As part of it, several well-known women artists interpreted real stories of victims of domestic violence. Notably, one of the most famous works in contemporary Kazakh art has been Zoya Falkova's Evermust (2017), which offers a profound exploration of this problem. Last year, it was purchased by the Museum of Forbidden Art in Barcelona, where it found a place alongside works by Pablo Picasso, Banksy, and Andy Warhol. Qalam explores the ideas behind Falkova's art and the controversies surrounding Evermust, reflecting on the deep sources of gender-based violence.

Poster of movie Bakhyt/ From open sources

Feminism That Should Liberate

Zoya Falkova was born in Almaty. She received an education in architecture and worked in that field for many years. She did not turn to art until much later in 2011, and since then, she has participated in over thirty exhibitions in the Commonwealth of Independent States and Europe. Zoya didn’t formally engage with feminist ideas until 2016; nevertheless, she has always felt the injustice of patriarchy.

‘People told me how I should be, and it didn't match me or my self-perception,’ says Falkova. ‘I think I began to be feminist the first time I heard someone tell me ‘But you're a girl!”’

Zoya Falkova /Roman Varlamov

Domestic violence is one of the main themes in Zoya's work. She explains that she grew up in an educated family, and that her father never raised a hand against her mother or the children, which is why encountering the ‘real’ world during her teenage years was traumatic. ‘Maybe it was because I was such a sheltered child that I found myself in an environment where violence was the norm, and I saw how prevalent it was,’ the artist explains. ‘Sadly, many young men will, more often than not, try to build rather abusive relationships, which, as a naive teenager, you do not expect at all.’ In the process of growing up, Falkova says she experienced enough violence from men to viscerally understand how gender imbalance works. But profound reflection on the issue came later, which opened up previously untouched creativity. Personal experience in Zoya's works is not immediately apparent. In the foreground is social criticism, an attempt to delve into the mechanics of violence itself.

‘It is a tool of patriarchy to maintain power,’ the artist explains. ‘If we magically took away the ability to commit violence from those who do it, patriarchy would falter, and the world would look entirely different. I see feminism as something practical. It should liberate women—and ultimately, only the decreasing and ending of violence can free us.’

The Birth of Evermust

Zoya’s art aligns with the conceptualist tradition, and her primary focus is the idea, for which she seeks the most precise and expressive form. The work should provoke thought in the viewer’s mind since a conceptual object is always a mystery. To solve it, one must first observe it and ask why every detail was added. For instance, Evermust, which is executed as a punching bag in the shape of a female torso with breasts but no limbs, evokes the preserved fragments of ancient statues of the goddess Venus. This is no coincidence. The artist created an image that is both ironic and tragic, a ‘Venus of patriarchal society’.

The inspiration for this piece emerged while preparing for the exhibition ‘Human Rights. 20 Years Later’, which took place in Almaty in 2017 and was curated by one of the most renowned figures in contemporary art in Kazakhstan, Valeria Ibraeva. Zoya explains that the concept came to her right while discussing the exhibition with Ibraeva. However, creating the piece, with the help of a friend who is a theater seamstress, took some time. As a result, to the curator’s discontent, Evermust appeared in the hall only half an hour before the exhibition opened. The public, however, did not always respond to the piece respectfully. For instance, when Evermust was exhibited in Astana, a well-known Kazakh poet, who was inebriated then, staged a real boxing match with the artwork and later had to pay for it to be restored. But the main scandal, which brought Falkova's work international fame, occurred at the 1st Feminnale of Contemporary Art in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, in 2019.

‘The opening of the exhibition itself was fairly quiet, and if it weren’t for the ensuing controversy, it would likely soon be forgotten. However, once images of the works appeared online, they triggered a strong backlash from political conservatives, who are not only numerous in Kyrgyzstan, but also have connections with the government,’ says the artist. ‘As a result, they came to the exhibition in kalpaks (traditional hats) and armed with kamchas (whips), threatening everyone present. They then held a press conference and forced the director of the Aitiev Museum, where the exhibition was being held, to resign. Finally, they pressured the government, complaining to the Minister of Culture, who showed complete professional incompetence by siding with the fanatics who want the world to look like something like present-day Afghanistan. He disregarded the constitution, personally censored the exhibition, and ordered the removal of six works, including mine. And so it came to pass that Evermust symbolized the actual events of the day.’

Zoya’s work was displayed next to the museum, and the ‘ban’ only increased public interest. The other participants of the exhibition wrote a letter of protest to the Kyrgyzstan government. Meanwhile, news of the ‘gender conflict’ in Bishkek spread through the global media. Falkova recalls that she had never given so many interviews in English as she did then. The attention the Kyrgyz traditionalists drew to Evermust not only made the artist and her work popular but also led to its inclusion in the Museum of Forbidden Art (all the works in this museum have been censored at some point) in Barcelona in 2023.

Zoya Falkova. Evermust. Artist with her work during the Women's March in honor of March 8th/Anton Platonov

Evermust and ‘It's Her Fault’

By referencing ancient statues in the creation of Evermust, Falkova creates a ‘Venus of patriarchal society’. The ‘convenient’ female deity is left helpless without limbs, evoking the thought: ‘She can't fight back!’ The image of the punching bag itself is notable as it is a static object until an external force strikes it and sets it in motion. It embodies complete passivity, submissiveness, the ability only to react to external signals, and the ability to move only in a given direction. Evermust is something like a faceless portrait—without eyes to have its own perspective and no mouth to express its own opinion. The title of the work is a conceptual pun. The sports brand Everlast—which Falkova translates as eternal and divine, associating it with traditional models of male upbringing—turns into ‘Evermust’ for a woman in a patriarchal family who ‘always must’ serve her husband.

One is reminded of Leos Carax, Michel Gondry, and Bong Joon-ho’s anthology film Tokyo!, where the heroine transforms into a chair to suit the wishes of her partner. Similarly, in a patriarchal family, a woman often turns into a punching bag. Thus, Zoya illustrates this depersonalization of a woman, stripping her of the intrinsic value of a living being. In a patriarchal society, a woman is reduced to a functional role and, essentially, an object that can be handled roughly. In addition, the artist emphasizes the sexual organs of the ‘sculpture’ for a reason as if to ask whether the difference between a sex object and a birthing machine is really that vast.

Unlike a real punching bag, Evermust is very light, making it almost impossible to practice boxing with it, a metaphor for a woman’s tenderness and vulnerability. Understanding the meaning of this work also involves observing how some viewers interact with it. On first seeing the punching bag, they reflexively want to hit it—and often do. This is an excellent illustration of how perceptions and interactions can be affected by upbringing, socialization, and functioning. For a man formed within this worldview, treating a woman as an object and domestic violence thus become almost instinctive behaviors. Thus, addressing domestic violence involves not only legislative reform but also a profound shift in societal attitudes and behaviors.

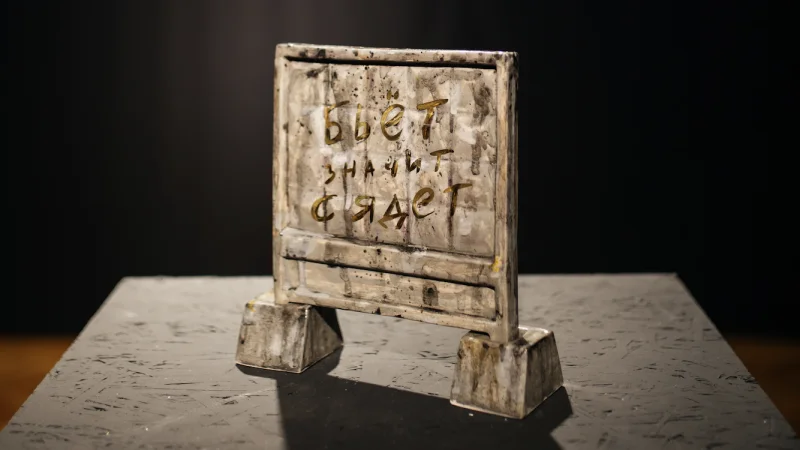

Zoya Falkova. If he beats - so he'll go to jail/Photo by Zoya Falkova

The titles of Falkova's works are telling of her beliefs and serve as linguistic evidence of how deeply rooted in culture the models that oppress women are. These include Evermust (2017), Her Fault (2018), You're Supposed to Be a Girl (2012), and the slogan ‘He Beats Means He'll Sit’ used in the ceramic artwork Tabletop (2022).

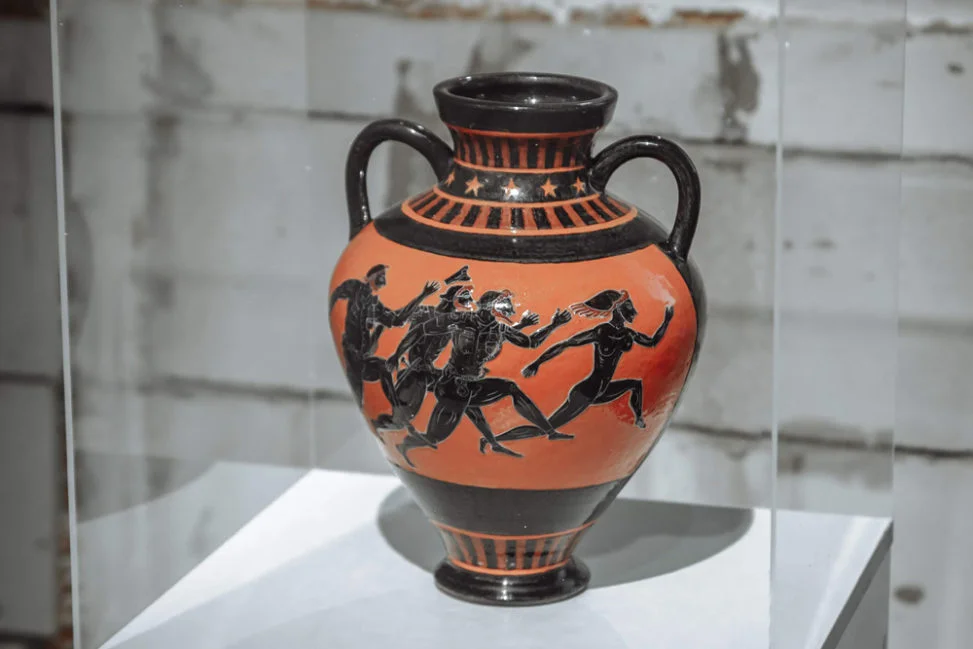

In Almaty, you can see another important work by Zoya Falkova, Her Fault, which is exhibited in the cultural space Art Lane. The artist once again refers to antiquity, but this time to the tradition of black-figure vase painting. Her persistent interest in classics is due to her belief that our contemporary struggles are rooted ‘deep in the centuries’, in the very foundations of European patriarchal civilization.

The vase painting depicts a swarm of male policemen, embodying authority, chasing a girl. The cynical phrase of the title seems to encapsulate the fate of women over the centuries, and the vase’s form turns the chase into an endless circular pursuit. Above, the stars observe the runners with satisfaction, giving the work a vertical dimension. Relationships between men and women are thus read as power dynamics and hierarchical.

Once again, this piece reflects societal ideals passed down from generation to generation, with the ‘circle runners’ being their captives. They resemble puppets or glove dolls manipulated by the invisible hands of these traditions. In ancient Greece, such vases, filled with olive oil, were awarded to competition winners. However, in the peculiar gender competition depicted by Falkova, victory is not about finishing first. For both the heroine and her pursuers, winning seems to be about getting off the track, about finally breaking free from the running track, catching their breath, and talking.

Zoya Falkova. Her own fault/Photo by Zoya Falkova