Cuckolds. French caricature. 1815 / Alamy

A woman will continue to give birth to children with characteristics inherited from her first sexual partner, irrespective of whether she has sex with other men. Remarkably, all her descendants will bear the enduring traits of the one who took her virginity. Skeptical? Well, advocates of telegony certainly stand by this belief!

The first elucidation of the concept of telegony is attributed to Aristotle, a reference available in both the Encyclopaedia Britannica and Wikipedia. The author of this article diligently scrutinized nearly all of Aristotle's works but found no semblance of this notion in the words of the Greek philosopher. The exploration could have been insufficient, or perhaps Aristotle chose not to delve into telegony at all, despite his ideas on conception and pregnancy occasionally revealing some remarkable insights.

The scientific determination of telegony only emerged in the nineteenth century CE, completely exonerating Aristotle from its origin. The architect of this concept was August Weismann, a precursor of modern geneticists. It was Weismann who postulated that hereditary traits from a woman’s previous partners could be transmitted to her descendants from subsequent males.

How did Weismann establish this premise? The truth is, he didn't. His view was merely conjecture. His argument supposedly elegantly clarified why there are instances of offspring not not resembling their mother, father, or any other known kin. During that time, the discourse on DNA's double helix, the intricate complexity of genes and their specialized functions, or the elaborate genetic roulette during gamete formation and conception had yet to emerge. The theory of telegony appeared to efficiently resolve these perplexities, but essentially, it was a minor hypothesis.

However, what stimulated Weismann even more was his (incidentally strikingly accurate) hypothesis that acquired traits do not transmit. He ardently opposed Darwin, who had considered the possibility of such inheritance. Weismann soared to fame through his experiments on mice involving the amputation of their tails. He bred these rodents by the hundreds, generation after generation, consistently docking their tails. And a breed of bob-tailed mice never materialized.

And what about telegony? It remained more of a cerebral amusement. August Weismann came up with an elegant term for this phenomenon, which was translated from ancient Greek as ‘telegony’ meaning ‘distant generation’, but he never really delved into the details.

He likely didn't foresee the frenzy his idea would incite in society. But a frenzy, indeed, ensued. Thousands of widows, those who had ventured into matrimony for the second or even third time, and their spouses hurled themselves into inspecting their offspring. Their quest? Discovering the traces of telegony!

Soon, educational pamphlets exhorting maidenly chastity in light of the latest scientific revelations began to be published. Meanwhile, Emile Zola wrote the poignant narrative Madeleine Férat: ‘Little Lucy bore a striking resemblance to Jacques. Despite having a daughter with Madeleine, Guillaume could not shape her in his likeness. The young woman's fertilized womb bestowed upon the child the traits of the man whose mark it carried. Fatherhood seemed to leapfrog over the husband, embracing the lover instead. Jacques's blood undoubtedly played a significant part in Madeleine's fertilization. The authentic father was the one who transformed the virgin into a woman.’

Telegony found swift and unwavering believers. While the kinship between humans and monkeys might be met with skepticism, telegony managed to hold a pair of aces in its favor. It catered to moral traditionalists and also provided an enthralling topic for refined soirées. There, amid the delicate clinking of china and tinkling of silver, the most indecent matters found their voice. Yet, remember, it was ‘science’ being discussed here. With the concept of telegony, science finally seemed to have tipped its hat to the boundless value of virginity and purity while simultaneously wagging its finger at second unions—an age-old topic of fervent dispute among the devout.

On another note, the Muslim world didn't quite cozy up to the concept of telegony because it went against Islamic doctrines and Sharia laws concerning marriage, divorce, and paternity. Sharia law, in no uncertain terms, dictates the duration that a widow or a divorced woman must bide her time to ensure that she isn't carrying her previous husband's child, after which she's free to seek a new partner—without any considerations about ‘womb imprints’ or other such nonsense.

Amidst all this, the only quasi-scientific nugget supporting the existence of telegony emerged through the tale of Lord Morton's mare, a story eloquently narrated by none other than Charles Darwin and his French counterpart Félix Le Dantec. The year was 1820, and Lord Morton’s bay mare was united with a quagga, a species of steppe zebra, on its last legs. Occasionally, such interbreeding could lead to offspring, and it was Lord Morton's lucky day: a hybrid foal with distinct stripes was ushered into the world—a zebroid as it was aptly christened. Admittedly, this zebroid didn't exactly champion the preservation of the quagga tribe; the steppe zebras had already bowed out of existence by the close of the nineteenth century CE. Nevertheless, after these scientific exploits, the same mare was paired with a white stallion, and lo and behold, the resulting foal sported markings faintly reminiscent of the quagga's stripes on its legs.

Contemporary geneticists, upon learning of Lord Morton's mare, typically responded with a nonchalant shrug: ‘A bay mare with a white stallion? Well, some recessive alleles must have made an appearance. Or perhaps an atavism decided to resurface. It happens.’

Subsequently, the ‘Lord Morton's mare’ experiment was conducted multiple times. Researchers explored trials with horses, pigs, dogs, and pigeons. Their endeavors were less driven by the goal of advancing science than by commercial motivations. After all, breeding with a pedigree bull or a prize-winning stallion came at an astronomical cost. The concept was tantalizing: lead a virgin mare just once to the distinguished Isinglass, a Triple Crown champion and the epitome of equine prowess. Later, pair her with any scruffy, nondescript Toby that crossed her path, and voila—she would continue birthing offspring of Isinglass’s class and distinction. Nevertheless, the experiment never yielded results for anyone—not even once. The females consistently produced progeny aligned with their current partners.

Today, armed with the knowledge of a decoded human genome and DNA tests that erase any lingering doubt about telegony's validity, its adherents aren't particularly hasty or willing to consign it to the archives of history. Various platforms and media intermittently broadcast exposés, asserting that the truth is being concealed from us by governments, scientific academies, and those perceived as sinister geneticists. Any discovery that even remotely insinuates the feasibility of telegony is promptly spread across every conceivable platform.

It is true that the females of certain species are adept at conserving male sperm for prolonged periods. Among them, many insects excel in this endeavor. Take ants for instance. During their nuptial journey, a queen engages in sexual relations with multiple males, amassing their genetic material to sustain her throughout her extensive lifespan. Meanwhile, specific fish species, like the ceratioid anglerfish (part of the sea devil family), portray a curious phenomenon: the male becomes affixed to the female and gradually degenerates, transforming into a mere extension of her form. This adjunct seamlessly integrates into the female's circulatory system, securing sustenance from her while dutifully furnishing her with gametes in return. Thus, in this format, telegony exists in nature. However, if an enthusiast of this theory isn't prepared to become a small appendage on his spouse's tail, he'll have to forsake the joys of telegony.

Recently, telegony has gained particular popularity in Russia. The second-to-last Commissioner for Children's Rights in the Russian Federation, Anna Kuznetsova, even earned the nickname ‘Telegony Mommy’ after an interview on television in which she shared the following: ‘Based on the relatively new science of telegony, we can assert that uterine cells possess informational wave memory. Hence, these cells remember everything that occurs within them. For instance, if a woman has had multiple partners, there's a significant chance of birthing a weakened child due to the mingling of information. This fact profoundly influences the moral foundation of the future child.’

One champion of this ‘informational wave memory’ in Russia is Petr Gariaev, whom official reports and academic articles refer to as nothing less than a ‘pseudo-scientist and charlatan’. His concept of the ‘wave genome’ isn't merely mistaken or incorrect—it's a stream of disjointed assertions detached from science and common sense.

But as is often the case with such myths, proponents of telegony require no evidence, logic, or scientific research. They don't talk to biologists or geneticists; instead, they target the most gullible and uneducated audiences, those who are willing to listen to fairy tales simply because they love and comprehend them. After all, they are far simpler and more entertaining than the fundamentals of genetics in school biology textbooks.

Incidentally, if the theory of telegony were scientifically accurate, it wouldn't be evolutionarily advantageous for women to remain chaste and monogamous. On the contrary, any young woman would be wise to attract, if only temporarily, the attention of the most handsome, healthy, intelligent, and robust man around her. This way, she could spend the rest of her life bearing his healthy, intelligent, and attractive children regardless of the qualities of her eventual spouse. So why enthusiasts of patriarchal norms have clung so tightly to this notion of telegony remains a puzzle to this day.

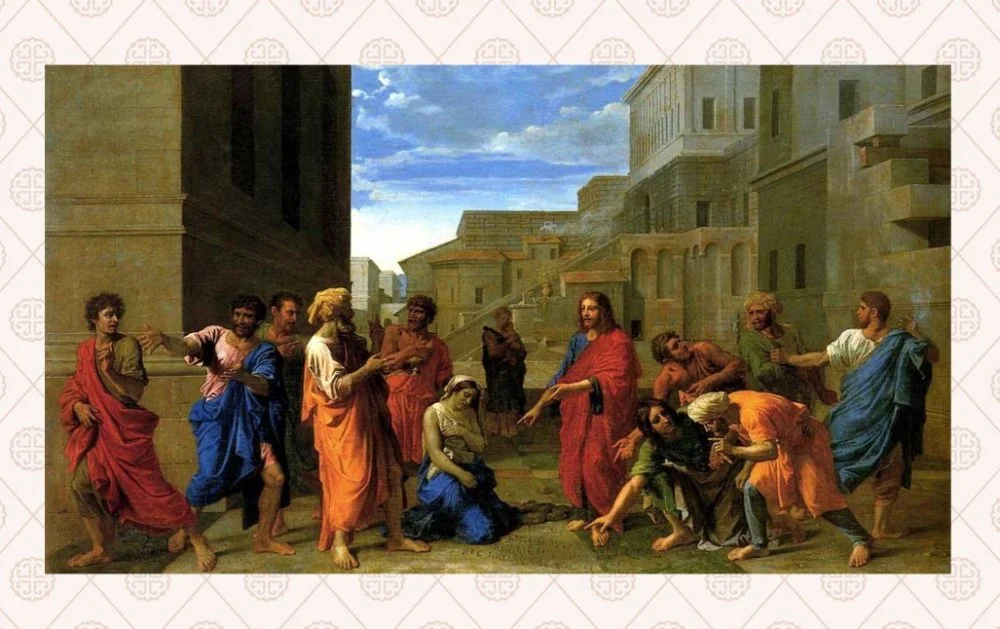

Nicolas Poussin. Christ and the sinner. 1653 / Alamy

What to read

1. Weismann, A. Lectures on the Theory of Evolution. A.F. Devrien Edition, 1918.

2. Muravnik, G.L. Myth-Making Instead of Preaching. Center for Christian Psychology and Anthropology, 2011.