Aminat Chokobayeva, a historian, on the Central Asian revolt of 1916 as the most crucial event in the history of Central Asia and Kazakhstan. The Russian Empire attempts to conscript the indigenous inhabitants of Turkestan for military service during World War I, the uprising and mouseholing of the nomads, and the reasons for the Tsarist government's failure despite the brutal suppression of the revolt.

In the early hours of a bitterly cold morning in November 1916, a rebel army consisting of 15,000 mounted fighters encircled the town of Turgai, a distant outpost of the Russian imperial government, in the Kazakh steppe. Their goal was clear: capture the town and overthrow the local authorities. While the uprising had erupted in response to the imperial authorities’ decision to conscript native men for forced labour, it was also driven by resentment about their oppression by colonial administrators. Though ultimately unsuccessful, the attack on Turgai town marked one of the most dramatic episodes in the widespread rebellion that soon engulfed the entire Central Asian region. The brutal suppression of this uprising came at an immense cost, with an estimated 88,000 killed among the native population, with another 250,000 exiled to eastern Turkestani

However, beyond the horrific loss of life, the uprising of 1916 had far-reaching consequences for the nomadic Kazakhs of the krais (or oblasts) of the Turkestan and Steppe Governor-Generalships, two vast administrative regions of the country.

The largest anti-colonial insurrection in the history of the Russian Empire, the uprising of 1916 was more than a manifestation of local grievances against the iniquities of the empire. There was another cause: the First World War was raging, and the strain and tensions it generated led to a broad range of conflicts that spread well beyond the battlefields of Somme and Ypres. It also marked the beginning of the collapse of the Russian Empire and presaged the violence of the Russian Civil War. At the regional level, the revolt led to the political mobilization of the native population and the consolidation of a political agenda that called for an end to imperial violence and the continued snatching away of nomadic lands.

What are the causes of the rebellion?

The uprising soon became a key topic in Soviet history studies—indeed, the first studies of the events of 1916 were published just a few years after the events took place. For the young Soviet regime, the uprising of 1916 provided an opportunity to take the separate history of the region and its peoples and merge it into the broader narrative of the October Revolution, which ‘liberated’ the colonized peoples of the Tsarist Empire. In fact, a number of new studies that revise this homogenized perspective have been published after the collapse of the USSR as well.

Yet, some aspects of the uprising remain poorly understood. Although most scholars agree that long-standing land dispossession was a key cause and the labor draft served as the trigger, opinions on the nature of the events of 1916 are divided. Was the uprising of 1916 an act of rebellion against a lawful government, or part of a movement for national liberation, or a spontaneous outburst of violence without organization and political goals? Studies of the various archives of the time show that the events of 1916 are best understood as an organized form of resistance against a colonist power by the native population. In the eyes of the people, the tsarist government lost legitimacy with its increasingly tyrannical actions, and open rebellion was the final and most violent stage of resistance. At first, those targeted for potential conscripts tried to flee—there were attempted negotiations with the authorities, and a refusal to produce the lists of eligible men. The colonial administration drew first blood by employing soldiers and police to threaten and coerce the Kazakh volosts (peasant communities or districts) into sending laborers. The decision to take up arms thus grew out of a series of increasingly hostile actions by the authorities: in response to the people’s non-cooperation and attempts to delay or prevent labor mobilization, the empire hit back with violence and murder.

Decree on labor mobilization. Signed by Nicholas II. June 25, 1916/Wikimedia Commons

Let us take a closer look at how the uprising unfolded in the two oblasts with Kazakh-majority populations, where the events of 1916 took their most dramatic course—the Turgai oblast of the Steppe Governor-Generalship (part of the present-day Akmola and Qostanai oblasts of Kazakhstan) and the Semirechye oblast of the Turkestan Governor-Generalship (part of the present-day Almaty and Jetisu oblasts).

Before discussing the uprising, it is necessary to take a close look at the conditions of the time, which set into motion the large-scale protests that eventually escalated into an open rebellion. The Turkestan and Steppe Governor-Generalships, which encompassed the territories of the present-day Central Asian states, were ruled by the Russian Empire as colonies. They were administered by the military, which performed executive and judicial dutiesi

Policy of resettlement of Russian and Ukrainian peasants to Kazakh lands

By 1912, a staggering 62 million desyatinasi

As Russian and Ukrainian peasants continued to occupy Kazakh lands, their growing numbers far surpassed the natural growth of the native nomadic population. Over a span of less than twenty years, between 1897 and 1914, the proportion of Kazakhs in the total population of the Steppe and Turkestan regions decreased from 74 per cent to 58.5 per centi

The growing settlements and the seizures of pastureland started to make pastoral nomadism unviable. In response to these challenges, a growing number of Kazakhs were forced to engage in seasonal farming during periods when their animals were not being pastured, while others, known as jataqs, had to settle down permanently. By the close of the nineteenth century, 32.2 per cent of Kazakhs were involved in farming in the Akmolinsk oblast, and 19.7 per cent in the Semipalatinsk oblast. Meanwhile, 11.3 per cent of the native population in the Turgai and 22.2 per cent in Ural’sk oblasts had become farmersi

Over a span of less than twenty years, between 1897 and 1914, the proportion of Kazakhs in the total population of the Steppe and Turkestan regions decreased from 74 per cent to 58.5 per cent. At the same time, the share of the Slavic population increased from 12.9 per cent in 1897 to 29.6 per cent in 1914.

The persistent encroachment upon native land inevitably sparked frequent conflicts between colonists and nomads, manifesting in fistfights, cattle rustling, and even instances of murder, all of which were routinely documented by colonial administrators. It is evident that the colonization of the Steppe region created a fertile ground for the emergence of a rebellion. However, the growing native resentment at settlers does not account for the timing of the Uprising, as organized mass attacks on government officials and colonists did not occur before 1916. The immediate context of World War I played a crucial role in propelling the simmering discontent into an armed rebellion. The deteriorating wartime economy, the implementation of the labour draft plagued by bureaucratic incompetence and insensitivity of the imperial government towards local conditions, and the callous treatment of the native population by local authorities all contributed to the intensification of previously suppressed grievances, eventually resulting in a violent conflict.

The beginning of World War I put a considerable strain on the native population of the region, exacerbating their already precarious situation. Still reeling from the jut and drought, which hit the western and northern oblasts of the Steppe between 1910 and 1913, Kazakh auyls were now targeted for frequent livestock requisitioning. i

The native population's deepening impoverishment, compounded by the loss of their land and the injustices of colonial rule, made for a tinderbox that could catch fire, but it was the labour draft, announced in the first half of July, that ignited the rebellion. The decision to draft the inorodtsy had been made in May 1916 as a response to the labour shortage caused by the departure of able-bodied men to the frontlines. The Council of Ministers planned to draft 230,000 men aged between 19 and 43 from the Steppe and 250,000 men from Turkestan. i

Representatives of Zhetysu cossacks. 3rd from left - military Governor-General of the Semirechensk region M.A.Folbaum. 1913/FOTO.KG

The decree was signed by Nicholas II on June 25 and the first announcements of the labour draft were made in the first half of July. The timing of the draft was inopportune, coinciding with preparations for the harvesting season. The wording of the decree also made it clear that the draftees would be transferred to “the area of active service by the army,” where they would be involved in “the installation of defensive constructions and military communications”. i

Tsarist Russian officials at the Pamir post. Turkestan. 1915 / Sir Percy Sykes / Wikimedia Commons

Individual announcements made by authorities did little to dispel these beliefs. Adding to the confusion, the governor of Semirech’e declared that native men were being drafted to dig trenches, leading many among the native population to conclude that they would be positioned between enemy lines. Meanwhile, in Turgai, the governor reneged on his earlier promises that Kazakhs were exempt from draft, further exacerbating the sense of panic and anger directed against the authorities. i

The first protests broke out as early as the first half of July in the sedentary areas of Turkestan. On July 4, 1916, a sizeable crowd of around 3,000 protesters gathered in front of the city administration in the town of Khojent (now Khujand in northern Tajikistan) in the Samarkand oblast. The following day, a crowd of approximately 2,000 protesters destroyed the lists of recruits. A group of protesters then attacked a punitive detachment sent to disperse the crowd. The protests swiftly spread to nearby towns of Dagbit and Gazy-Uaglyk. Within days, the Samarkand oblast was aflame. By July 9, new protests erupted in Andijan, which later spilled over to Margilan, finally reaching the capital of Turkestan, Tashkent, on July 11.

The events leading up to the rebellion unfolded differently in the Kazakh Semirech’e. The simmering discontent with the draft did not immediately translate into direct confrontations with the authorities. Instead, the Kazakhs of Semirech’e directed their frustrations towards native administrators. With the disturbances in Turkestan unfolding before their eyes, Semirech’e administrators sought to pre-empt protests by arresting and threatening violence against native “agitators”. During the latter part of July, the authorities cracked down on individuals suspected of agitating against the conscription. Numerous arrests were made, with 34 alleged agitators arrested on a single day on July 17 across three volosts of the Verny uezd (now part of Almaty oblast). i

The first hostilities in Semirech’e occurred in the last week of July, when a group of Kazakhs fleeing the draft opened fire on a border patrol that attempted to apprehend them. The incident at the border was soon followed by clashes in the Kyzylburovsk and Botpaevsk volosts of the Verny uezd between August 3-6. The incident in the Kyzylburovsk volost was caused by the actions of the deputy head of the uezd, Khlynovsky, who took hostage several Kazakh notables to coerce the volost into submitting the lists of recruits within the span of five hours. The volost representatives made repeated appeals to Khlynovsky requesting him to release the hostages and delay the draft. However, tensions escalated when, in an attempt to disperse the increasingly agitated crowd, Khlynovsky fired into the air. Believing this was an order to open fire on the crowd, Khlynovsky’s men shot two Kazakhs. A protester armed with a hunting rifle fired back, killing one of the policemen. Following the incident, a Cossack cavalry squadron and a half-company were despatched to the volost. i

The second incident in the Botpaevsk volost unfolded in the nearly identical fashion. The arrival of the district police captain Gilev and twenty policemen resulted in the killing of twelve Kazakhs and the despatch of a punitive expedition consisting of a Cossack company, one infantry company, and a settler militia, which murdered indiscriminately on their way to Pishpek. A report by a native official, Mukhamedzhan Tynyshpaev, suggests that indiscriminate murder of the native population was employed even in areas where no disturbances had taken place, such as the Kopal uezd (part of the modern-day Jetysu oblast), where local Cossacks killed 40 Kazakhs. In the Lepsinsk uezd (now part of the Jetysu oblast), the unrest, which claimed no victims among the colonists, led to the killing of 100 Kazakhs and the arrest of another hundred.

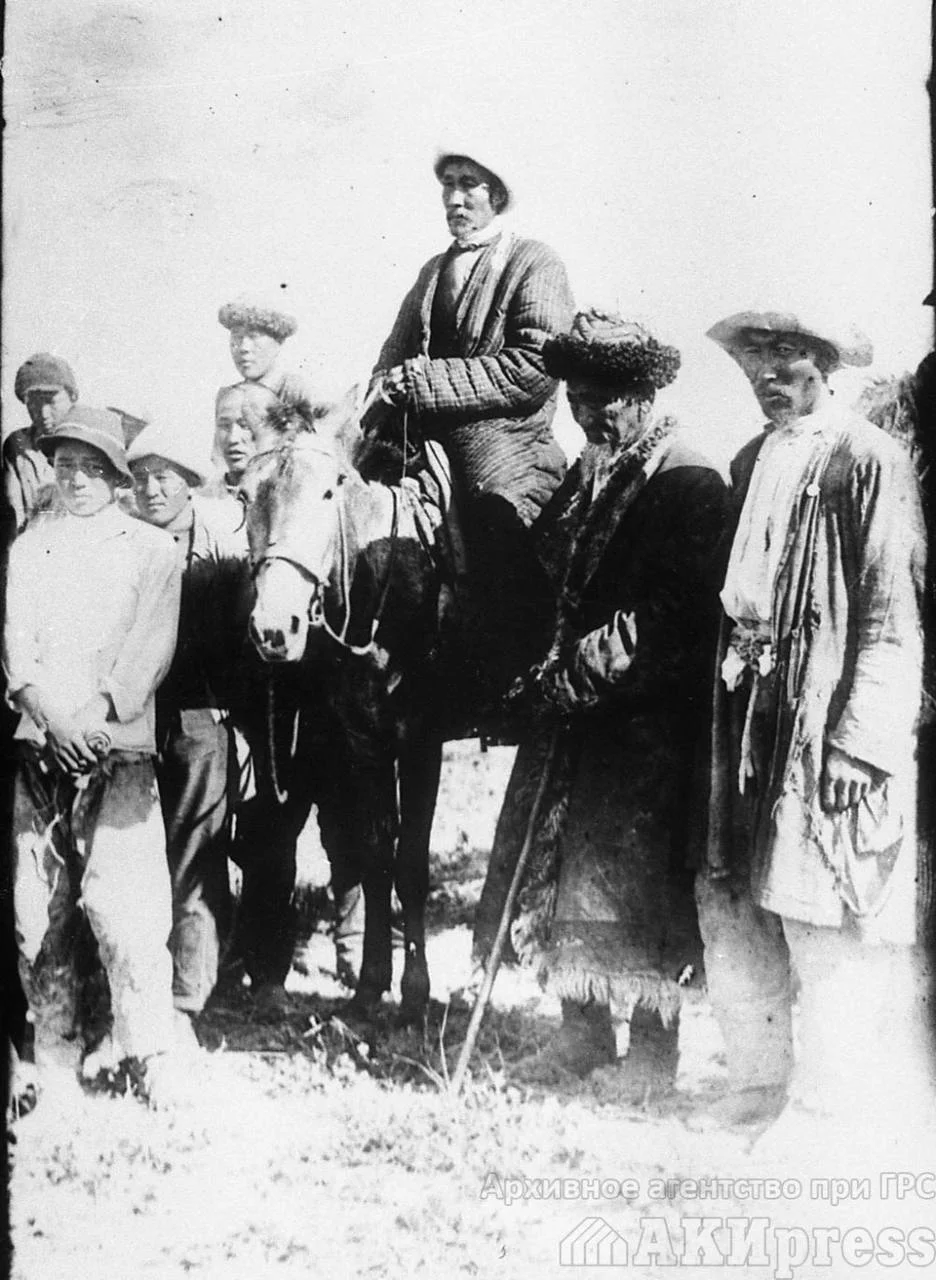

Participants of the uprising/AKIpress

These incidents highlight a clear pattern: the use or threat of violence by the authorities often elicited a violent response from the nomads. The efforts to intimidate the native population and suppress any form of opposition to the draft likely convinced many in the native society that they faced a grim choice: either perish on the frontlines fighting the German army, engaged in arduous trench-digging, or face death at the hands of the punitive forces at home. The indiscriminate violence inflicted by the Cossacks and soldiers upon innocent auyls and families, who had neither protested nor participated in the disturbances, lent credibility to the rumours that the authorities harboured a sinister agenda to destroy the nomads. A poignant remark by a Kazakh judge in the Zharkent uezd (part of the modern-day Almaty oblast) that the Muslims would not be “conscripted like sheep taken to slaughter” is a telling testament to these beliefs. i

Following the incidents in Kyzylburovsk and Botpaevsk volosts, the now rebellious Kazakhs cut off telegraph lines and launched attacks on post relays along the Verny (Almaty) to Pishpek (Bishkek) road. The rebels also made unsuccessful attempts to capture several settler villages, and captured peasants who were working in the fields. i

The sequence of events leading to the uprising in the Turgai oblast paralleled those that occurred in Semirech'e. Following the announcement of the draft, Kazakhs of Turgai sent a delegation to Petrograd with the request to delay the mobilization. i

The initial disturbances of September soon gave way to a brief period of relative calm, abruptly shattered in late October. The likely explanation for the lull in the months preceding the uprising is that the Turgai Kazakhs organised and prepared for armed resistance. They mobilized men, forged weapons, and pooled resources. Indeed, the available archival evidence suggests that the Turgai rebels had higher level of organisation and coordination compared to their kin in Semirech’e. Notably, the Turgai rebels established two distinct de-facto armies, which consisted primarily of Argyn and Qypshaq tribesmen, and had military commanders. One of these commanders, Amangeldy Imanov, was immortalized in the Soviet historiography of the uprising. The Turgai rebels also had political leadership; Amangeldy commanded the army of Abdulgafar Janbosynov, elected as the khan of the Qypshaq tribe. The Argyn rebels were led by Ospan Chulakov. i

The actions of the Turgai rebels closely mirrored those in Semirech’e. To impede the advance of the punitive forces, the Turgai rebels destroyed a 160-verst (170-kilometre) stretch of the road i

On October 22, the rebellious Kazakhs began the siege of the town of Turgai that lasted until the end of November. In the early hours of November 6, the rebel army launched a fierce assault on the town. According to eyewitness accounts, 12,000 mounted fighters charged on the town in four columns. Although failing to capture the town, the rebels inflicted significant damage by destroying approximately 100 houses on the outskirts of Turgai and setting fire to the surrounding hayfields, reeds, and bulrushes. i

Muslim hunters of Zhetysu, near the town of Verniy/Pavel Leibin/ "Folbaum's Album", 1913

In the following months, the punitive forces, which now included 17 infantry companies, 19 Cossack companies and squadrons, 14 field-guns, and 17 machine guns, continued to engage the rebels in the steppe with varying degrees of success i

In contrast, the uprising in Semirech'e was ruthlessly suppressed by October. The punitive forces dispatched to the region were significantly larger compared to those in Turgai, consisting of 35 companies, 24 Cossack cavalry squadrons, 240 mounted scouts, and various settler militias. They were equipped with 16 field-guns and 47 machine guns i

How many Kazakhs were killed by the punitive expeditions in Semirech’e and Turgai is difficult to determine due to the lack of official records. The Kyrgyz historian Dzhenish Dzhunushaliev estimates that approximately 16,000 Semirech’e nomads lost their lives during the clashes with punitive forces throughout the course of the uprising and the subsequent mass migration to China i

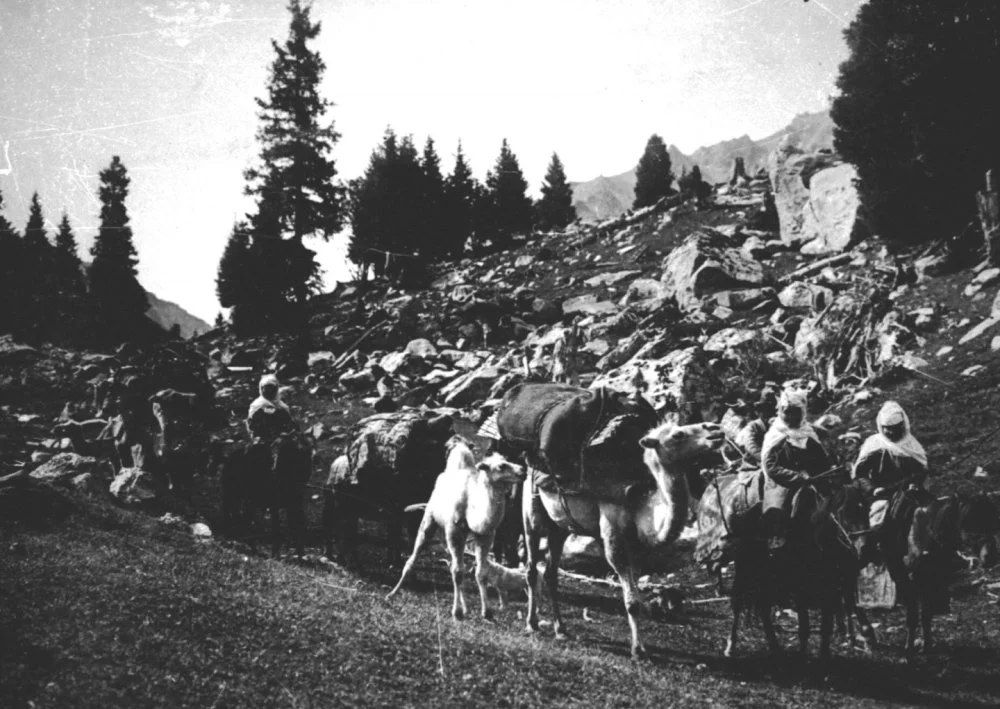

We can say with certainty that thousands of nomads lost their lives at the hands of soldiers and Cossacks, while an even larger number perished while attempting to flee. In Semirech’e, the flight of Kazakhs to China in search of safety resulted in immense suffering and hardship.

The demographic statistics reveal a significant decline in the native population of the three Kazakh uezds in the Semirech'e oblast. By January 1917, the Kazakh population in the Verny and Lepsinsk uezds had nearly halved. The Verny uezd experienced a loss of 1,932 households out of a total of 4,347, while the Lepsinsk uezd recorded a loss of 3,442 households out of 7,071. However, it was the Zharkent uezd that suffered the most substantial population loss, with 12,718 households out of 17,096 fleeing the uezd. i

In total, anywhere between 164,000 and 250,000 Kazakhs and Kyrgyz sought refuge in Eastern Turkestan. i

Pavel Leibin. Migration to the mountains. 1913/ Folbaum's Album

The fate of those who remained in Semirech’e was equally dire. Despite the promises of national equality, the February Revolution did not bring any relief to the afflicted communities. A petition submitted by the Kyrgyz and Kazakhs of the Pishpek uezd to the Provisional Government painted a bleak picture of the relationship between the colonists and the indigenous population: “the Russian peasants…threaten to kill the Kyrgyz. There is no rule in the uezd and no one to protect us”. i

The anguish experienced by the native society in the wake of the uprising finds expression in folk songs, poems, and family histories. Among these, the song “Samaltau,” composed at the time of the uprising and recently performed by Dimash Qudaibergen, among many others, stands out as a prominent example. Through the voice of a conscripted young man, the song portrays the soldier’s apprehensions about his own future and the well-being of his elderly parents. It also serves as a poignant lament for the tragic fate of the “wretched people” (qairan el) who were beset by hardships and sorrow. Another notable example of popular reflections on the events of 1916 is the poem “Tar Zaman” (Time of Troubles) written by the renowned aqyn Sartbai. In the poem, he pours scorn on the Tsar for ruining and inflicting violence on Kazakhs. Similarly critical of the Russian emperor is poet Isa Baizakov, who compares Nicholas II to a leech sucking the blood of the Kazakh people. “My innocent homeland, what have they done to you?” he laments before sorrowfully responding that they (the Tsarist forces) “made your daughter into wife, your shanyraq into firewood” and “washed the country with blood.”

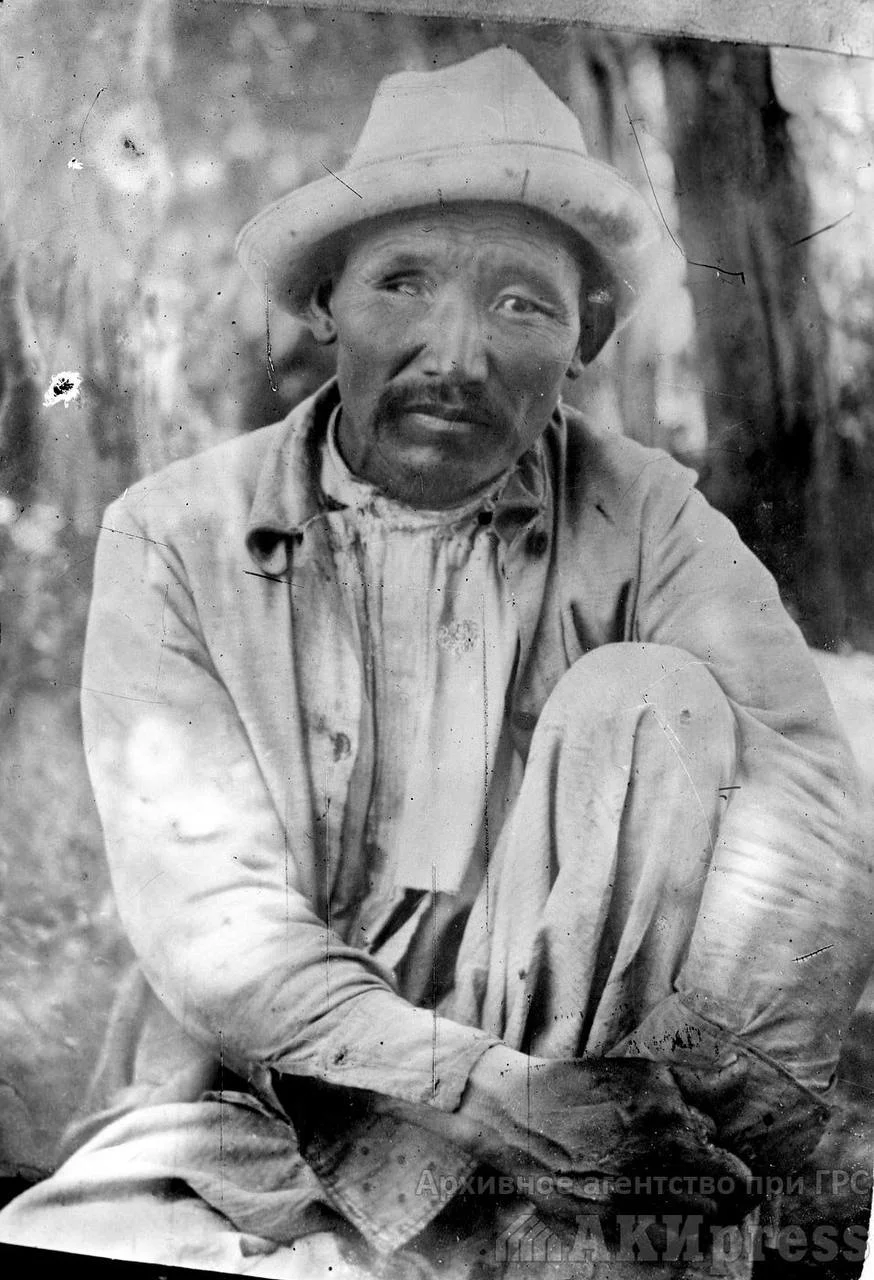

Kyrgyz – participant of the uprising of 1916/AKIpress

Despite the brutal suppression of the uprising, it would be a mistake to think that the imperial government benefitted from the destruction it inflicted upon the native communities. The actions of the punitive forces further alienated the native population of the region and created a sense of siege among the settler society. The suppression of the uprising also diverted the vital resources from the front, weakening the war effort, and made the central government a target of pointed critique in the State Duma. Furthermore, the draft proved largely unsuccessful. Out of the intended 480,000 workers to be mobilized from Turkestan, only a quarter, or 123,205 men, were actually recruited. i

More importantly, the uprising shaped in profound ways the dynamics of the civil war pitting the native and settler societies. From the perspective of the native nomads, the civil war was seen as an extension of the conflict that began in 1916. The settler society also viewed the civil war through the lens of competition for native land and resources. The arming of colonists in the aftermath of the uprising enabled settler communities to assert their dominance over the native population and navigate the civil war with minimal losses. It is a little surprise then that Akhmet Baitursynov described the civil war in the Steppe as marked by “violence, looting, abuses, and a peculiar dictatorial power”. i

On the other hand, the uprising and the subsequent civil war had a mobilizing effect on the native society, allowing the native intelligentsia to establish strong ties with the native communities they sought to represent. In the aftermath of the uprising, numerous members of the Alash served as translators and intermediaries between the drafted men and the authorities. They negotiated and petitioned the government in Petrograd on behalf of the Muslim labourers from the region. In the words of the Japanese historian of Alash, Tomohiko Uyama, these efforts made them both “larger and more popular” with the native laborers. Equally significant, the Alash leaders recognized the land issue as a crucial factor behind the uprising and made it a central component of their political agenda. The political programme of the party focused on demanding an end to the colonization of the Steppe and Turkestan, as well as equal land rights and political representation for the nomads. In the course of the civil war and the bloody struggle for control in the Steppe, these demands transformed into calls for national autonomy for the native population. Ultimately, as one scholar put it, “the Revolt of 1916 was both the prelude to the Revolution in Russia proper and the catalytic agent which hastened the alignment of forces in Russian Central Asia.”