If there was ever a city that could leave a traveler dazzled in the ninth century, it was Baghdad. In fact, ‘To see Baghdad and die’ could have been a famous saying for that time. At its peak, it was not only likely the most populous city in the world, but it was also at the forefront of science, trade, and culture. Think of it as the medieval equivalent of modern-day New York with a touch of Arabian Nights magic—and amenities like a sewage system. So, if you’re up for a donkey ride, a spa day, or a visit to the largest library in the world, Baghdad is the place you want to be.

- 1. The Best Century to Visit Baghdad

- 2. Getting There

- 3. Baghdad’s Greatest Eras

- 4. Payments and Currency: How to Pay

- 5. The Language of Baghdad

- 6. Where to Stay

- 7. How to Keep Track of Time

- 8. Getting Around the City

- 9. Places to Visit

- 10. The Flavors of Medieval Markets

- 11. Dining Etiquette

- 12. What to Do If Wine Is Served

- 13. Exploring Ancient Baghdad

- 14. What to Wear in Baghdad

- 15. Anything Else You Should Keep in Mind?

- 16. What To Do In Case of a Problem

- 17. Leaving Baghdad

- 18. What to read

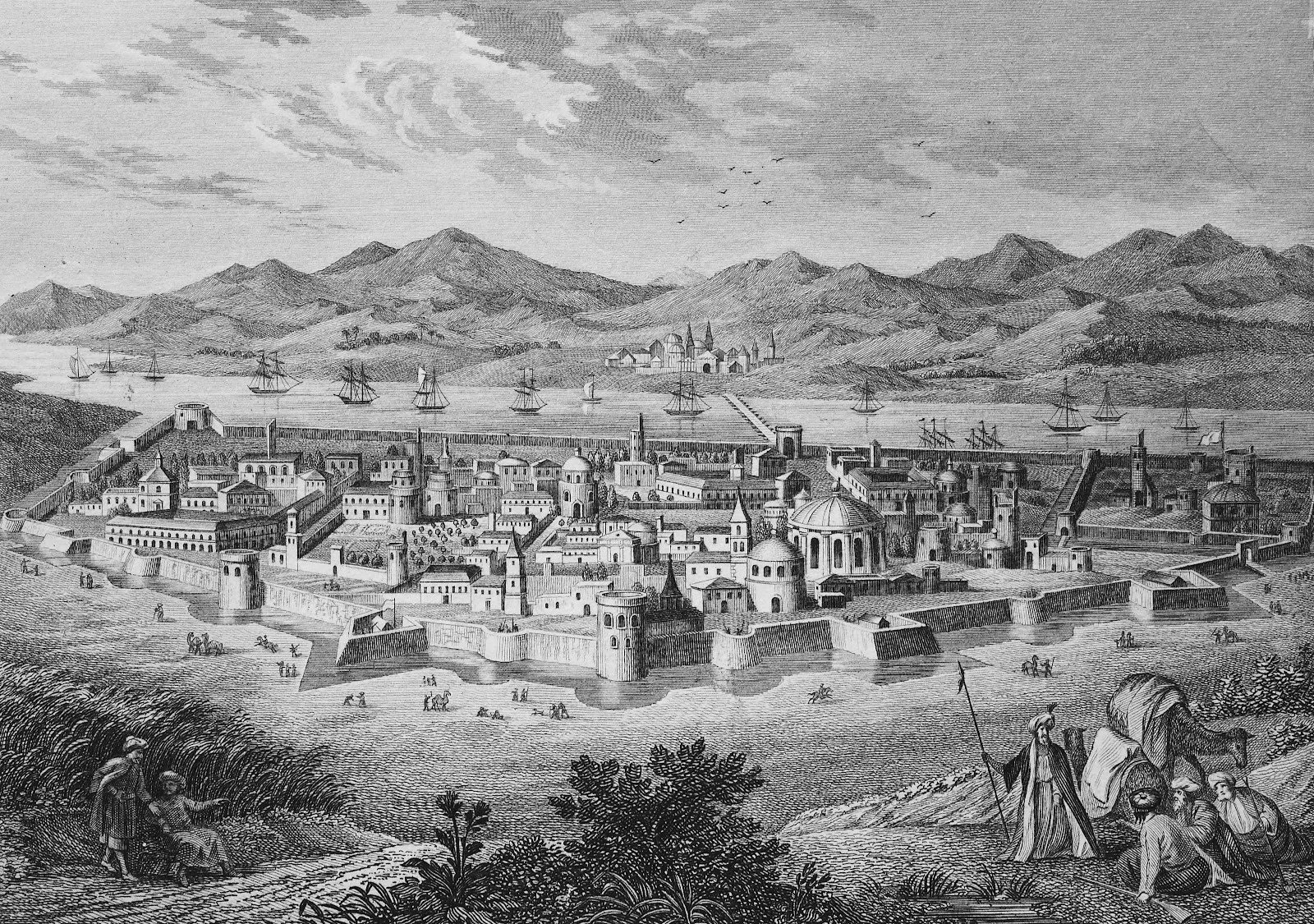

Baghdad was the capital of the Arab Caliphate, stretching from the borders of China to the Atlantic, from the Arabian Sea to the Caucasus Mountains. At this time, 1,200,000 people lived in the city, and it was always bustling with visitors—officials on state business, merchants on trade missions, relatives visiting from afar, travelers, performers, and wanderers.

The Baghdadis themselves were also a diverse mix of ethnicities, faiths, and languages. Along with Muslims, the city was home to Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians. The ethnic mosaic spreading into the city was even richer: Arabs, Persians, Copts, Jews, Greeks, Syrians, Indians, and many others coexisted within its walls.

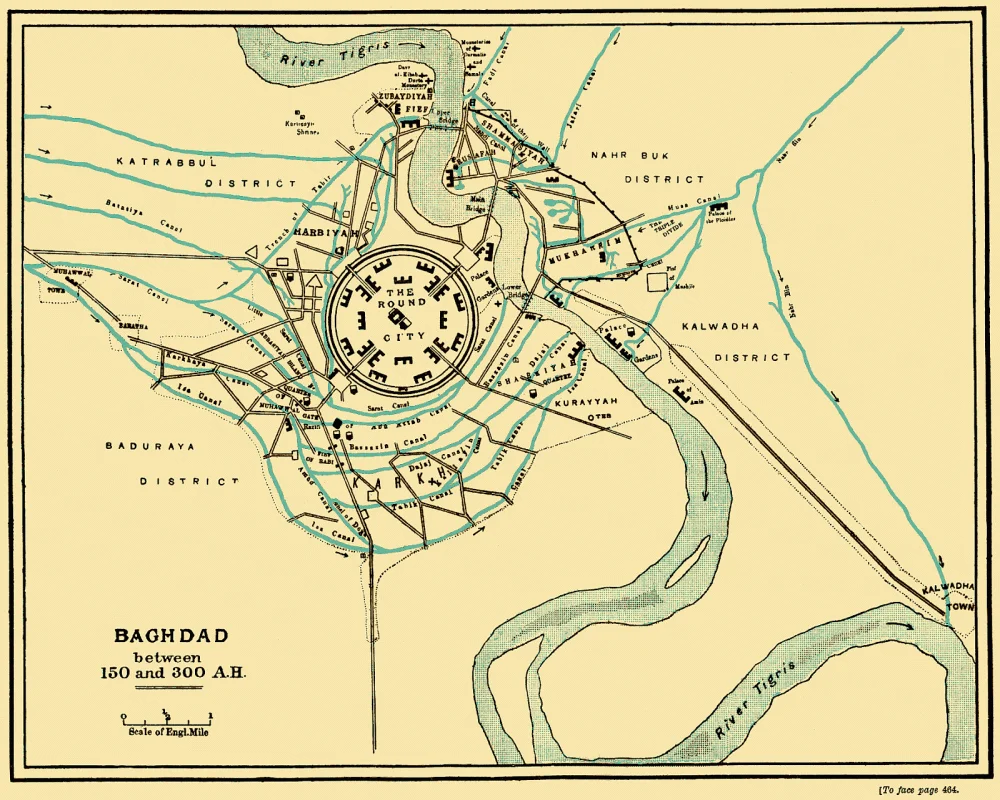

William Muir. Map of Baghdad (150–300 AH / 767–912 CE). 1883 / Wikimedia Commons

The Best Century to Visit Baghdad

Baghdad was a young capital, built between 762 and 768. By the ninth and tenth centuries, the city had reached its peak, the perfect time to visit and witness its ancient splendor. However, from the mid-tenth century onward, Baghdad gradually fell into decline and became an increasingly unsafe place.

Getting There

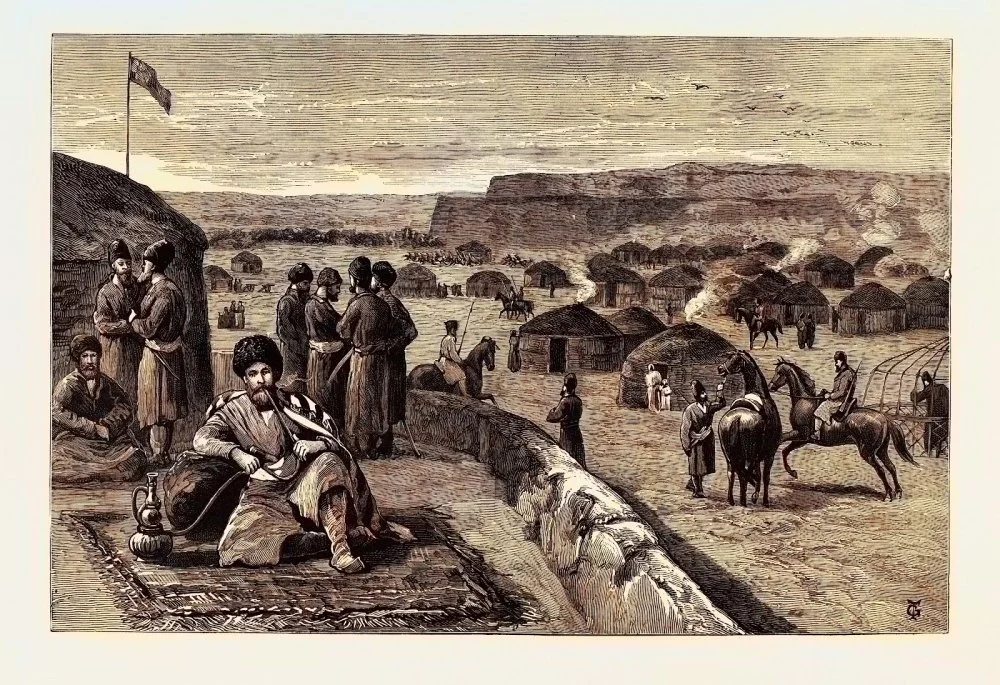

The easiest way to get there is to travel with a caravan from Central Asia. For instance, you could set out from Taraz and join a trade caravan passing through Shash (Tashkent), Samarkand, Bukhara, and Merv and then continue through the Iranian cities of Nishapur, Ray, and Hamadan. This was the classic route connecting Baghdad to the East and vice versa. Merv, for example, was known to the Arabs as the ‘gateway to China’.

Remember that at this time, caravans traveled at an average speed of 20 to 40 kilometres per day, and the journey, including all necessary stops, would take about three to four months.

Mr. O’Donovan’s Journey Through Central Asia: The Fortress of Merv. Illustration from The Graphic, 1882 / Getty Images

But don’t worry—you will find caravanserais, regional inns for merchants and travelers, along the way. Just make sure to pack your own bedding and other necessities as the availability of water at these inns is often inconsistent .

On the bright side, you won’t have to worry about bandits—caravanserais were always fortified with strong walls. And if the caravanserai is in a large city, you can even find a chaikhana (tea house) there.

Caravanserai, Meybod, Iran / Getty Images

Baghdad’s Greatest Eras

The best time to visit is from September to March, when the heat subsides and the city goes from celebrating one festival to the next. Cosmopolitan Baghdad enthusiastically celebrated Muslim, Christian, and Zoroastrian holidays alike. For example, on the last Saturday of September, don’t miss the Fox Monastery Festival near the Iron Gate in western Baghdad. This area is famous for its lush parks, gardens, and greenery, and is located right in the heart of the city.

On 3 October, take part in one of Baghdad’s most vibrant festivals held at the Christian Monastery of St. Eshmuna in Qutrabbul in the northwest of the city. People travel there on barges and boats large and small, bringing along wineskins and musicians. The wealthy set up tents on-site, and for three days and nights, the banks of the Tigris are filled with revelry, ‘illuminated by the glow of candles and beautiful faces’.

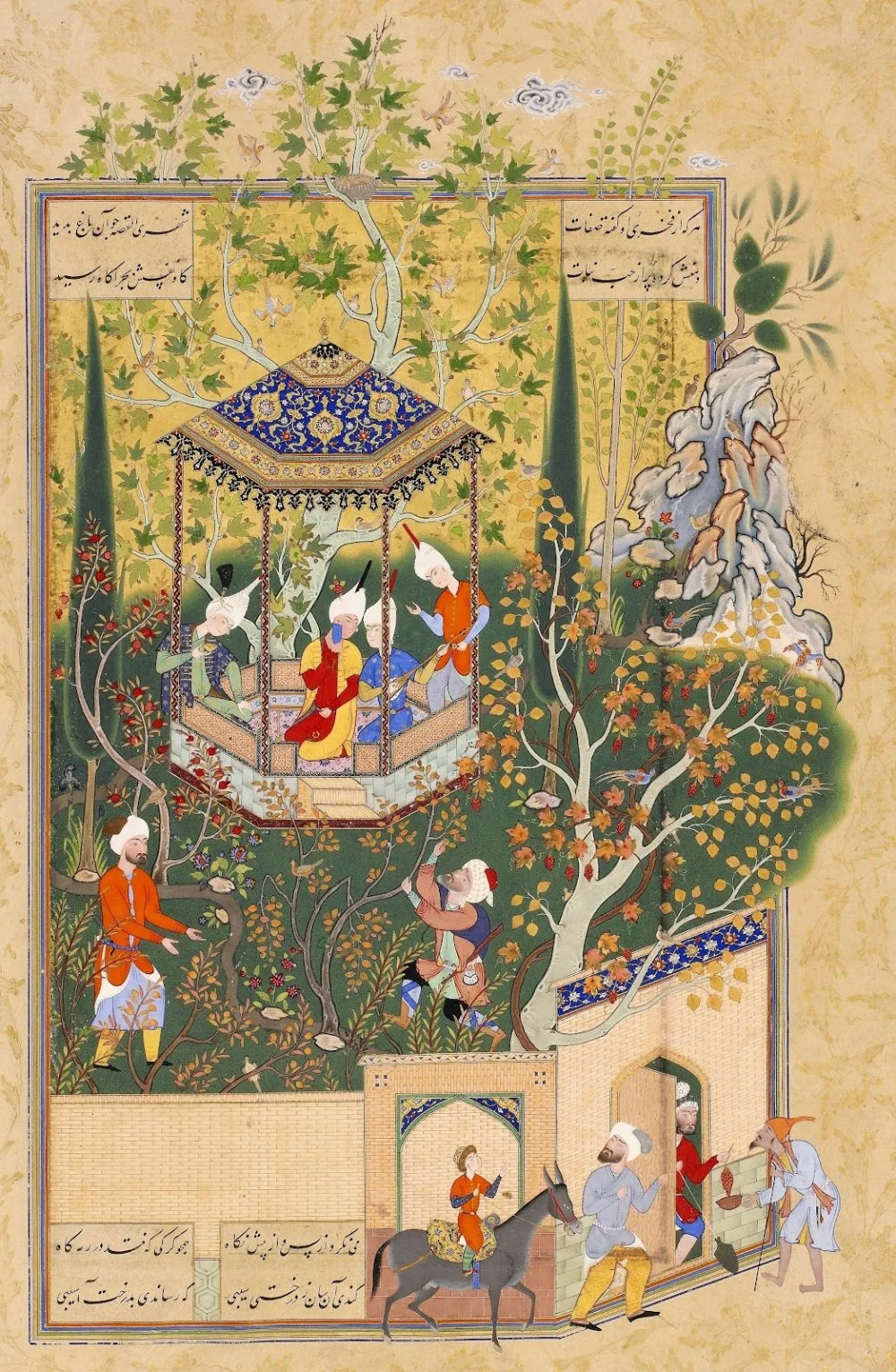

Mir Sayyid Ali. Palace Life. Circa 1540. Harvard University / Wikimedia Commons

On 25 December, come to the city to celebrate Christmas, the birth of Jesus Christ. The people of Baghdad light fires and burn incense in their homes, while the wealthy build large bonfires. Some even burn animals or release birds, an old pagan tradition that is increasingly being condemned in harsh language:

May Allah take revenge on anyone who takes pleasure in the pain of other sentient beings that cause no harm!

However, the grandest celebrations take place in spring: Eid al-Fitr (Orazа Ait), Eid al-Adha (Qurban Ait), and Nowruz. Remember, though, that these holidays follow a lunar calendar, and their dates vary each year. Alongside traditional feasts and festivities, you might also witness fire processions for Nowruz, while camels are often chosen for sacrifice during Qurban Ait.

Payments and Currency: How to Pay

Baghdad uses silver dirhams and gold dinars. Baghdad is not a cheap city, so bring a generous amount. Since paper money doesn’t exist in the caliphate, you'll need to carry precious metals like silver or gold. At the exchange rates of that time, 1 dirham weighed about 3 grams of silver, which is roughly equivalent to 1,600 tenge.

In Baghdad, you can exchange silver for coins through moneychangers, who are always easy to find in the markets. On average, one gold dinar equals 20 dirhams. Smaller denominations, known as fals, follow a base-6 system:

1 dirham = 6 daniqs = 12 qirats = 24 tassujes = 48 habbas

For example, a meal for two—roast meat, some wheat bread with sauce, an almond pie, and iced water—will cost you about 20 daniqs (around 5,000 tenge /$9.90 USD).

Your total expenses will largely depend on your lifestyle. Your biggest cost will be getting from Baghdad and back, a journey that could set you back anything ranging from 5,000 to 10,000 dirhams. However, once you are in the city, life is surprisingly affordable. In fact, locals manage on about 1 dirham per day, excluding housing costs.

Silver Dirham from the Abbasid Caliphate during the reign of Al-Ma’mun, minted in Herat, Khorasan, between 813 and 833 CE. Private Collection / Getty Images.

The Language of Baghdad

The official language of the caliphate is Arabic, but Persian is also widely spoken. If you’re more comfortable with Kipchak dialects, Syriac, Middle Greek, Hindi, or even Latin, finding a translator will be easy. Many translators also offer guide services—a valuable resource in medieval Baghdad—so don’t turn down the offer.

Where to Stay

Your guide will point out several inns that will suit your budget—you can trust his judgment without worrying about poor hygiene or unpleasant odors. The hospitality industry in Baghdad is well-developed with standards befitting its status as the capital.

Interior of a traditional house, Baghdad, Iraq / Getty Images

If you prefer a more private stay, the guide will find you a small house. Houses in Baghdad are privately owned, and the rental market is also well-developed. You can rent a fully furnished home, often with household staff. A small two-story house with a basement costs about 1.5 dinars per month or 2 dirhams per night for short-term stays.

Interior vaulting of Khan Murjan, Baghdad, Iraq. Constructed between 1356 and 1358 by Amin al-Din Murjan, the Jalayirid governor of Baghdad. / Alamy

If a Baghdad-born travel companion invites you to stay at their home, don’t hesitate to accept. Curiosity about the world and generosity toward guests are deeply ingrained in local customs. Your host can afford it and will gladly share a meal and conversation with you—without expecting a single dirham in return. You will be well cared for by their household staff and the people assigned to attend to you, yet without any burdensome or intrusive obligation to socialize more than you wish. This, too, is a hallmark of Baghdad’s refined etiquette.

How to Keep Track of Time

There are no clocks as we know them in Baghdad at this time. Instead, sound will be your guide. The city has 27,000 places of prayer and two grand mosques—one on each bank of the Tigris—from which the call to prayer rings out five times a day. In the caliph’s palace, the guard announces prayer times by beating drums and kettledrums and by sounding trumpets. Interestingly, these symbols of the ruler’s supreme authority are usually suspended during periods of court mourning. Some officials also have drums beaten in front of their homes to mark prayer times. Meanwhile, church bells ring in the morning and evening to signal Christian services.

Getting Around the City

The most common mode of transportation in the city is donkeys. The main donkey stand is at the Al-Karkh Gate near the entrance to the business district. A single ride costs two kirats. Another option is traveling along the Tigris on rented ‘Sumerian boats’, of which there are more than 30,000 available.

Abd al-Aziz. The Townsman Robs the Villager’s Orchard, miniature from Jami’s poem “Haft Awrang”. Circa 1556–1565. Freer Gallery of Art / Wikimedia Commons

In many ways, Baghdad resembles Venice: people arrive, depart, and cross by boat; two-thirds of the city's wealth rests on the river. Cargo ships dock at various bazaars, and narrow streets wind over high stone arches spanning the water. Floating bridges, made up of boats lashed together, connect the eastern and western banks of the Tigris and are drawn apart to let ships pass through.

Passengers landing in circular boats (guffa) on the Tigris River, Baghdad. Engraving from The Illustrated London News, 1853 / Getty Images

The river is bustling with government and private vessels of all sizes, hosting high-level meetings, celebrations, and leisurely excursions. Large sailboats are often crafted in the form of animals, depicting lions, elephants, eagles, horses, dolphins, snakes, or gazelles.

The young man of Baghdad reveals his true identity to the Hashimi. Illustration from the Tuti-nama (Tales of a Parrot), Forty-eighth Night. Mughal India, circa 1560. Cleveland Museum of Art / Wikimedia Commons.

Horses are ridden not only by the military and the male aristocracy but by anyone who can afford them, including women. Trade caravans use camels and cargo ships to transport goods across huge distances. Meanwhile, noble ladies travel in the privacy of a palanquin, remaining concealed from public view as they go across the city.

Places to Visit

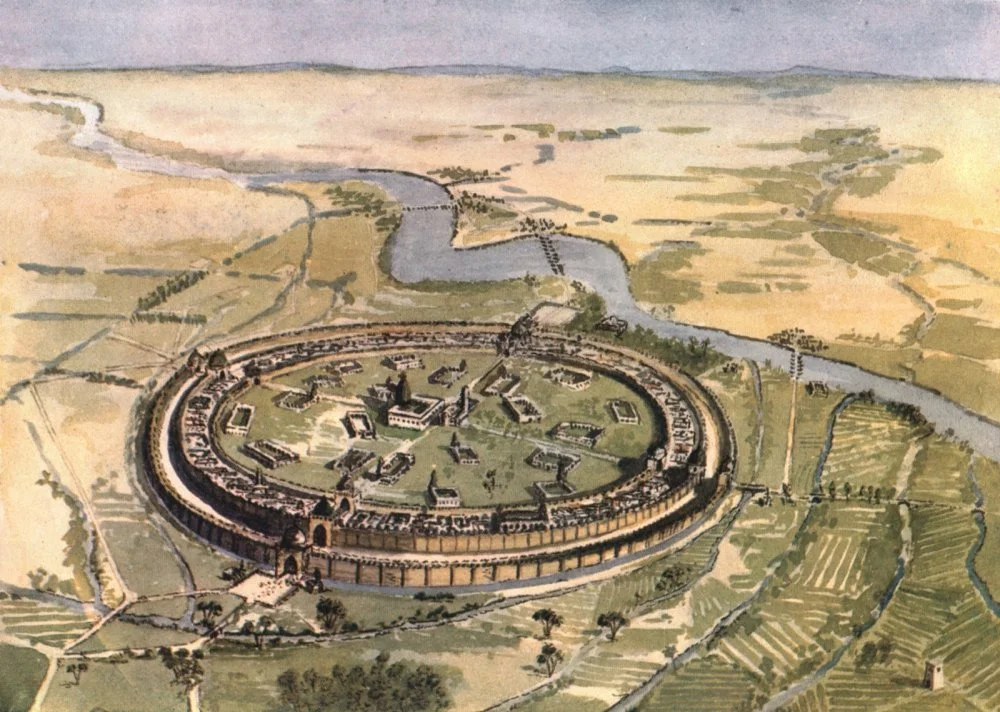

Madinat al-Mansur (The Round City)

The oldest part of the city, essentially the heart of Baghdad and its main attraction, lies on the western governmental bank of the Tigris. It is a walled, circular city with gates, centered around the Palace of the Golden Gate and distinguished by its massive green dome. Inside and around this ‘city’ are numerous districts, gardens, ponds, and canals. The area is also home to the palaces of nobles, military commanders, and relatives of the caliphs.

“Baghdad in the Days of Mansur,” 1915. Reconstruction of the walled city as it might have appeared in the 8th century during the reign of Caliph Al-Mansur / Getty Images

Be sure to see these places, even if only from the outside, as you are unlikely to be welcomed as a guest unless you resort to the cunning tricks celebrated in One Thousand and One Nights. Perhaps you could disguise yourself as a fabric merchant or a fortune teller and hope that it works! In the near future, many of these buildings will be destroyed, be rebuilt, or fall into ruin. The Abbasid Palace, one day a major landmark in Baghdad, would only be constructed in the twelfth to thirteenth centuries, long after the grandeur and power of the caliphs had passed into history.

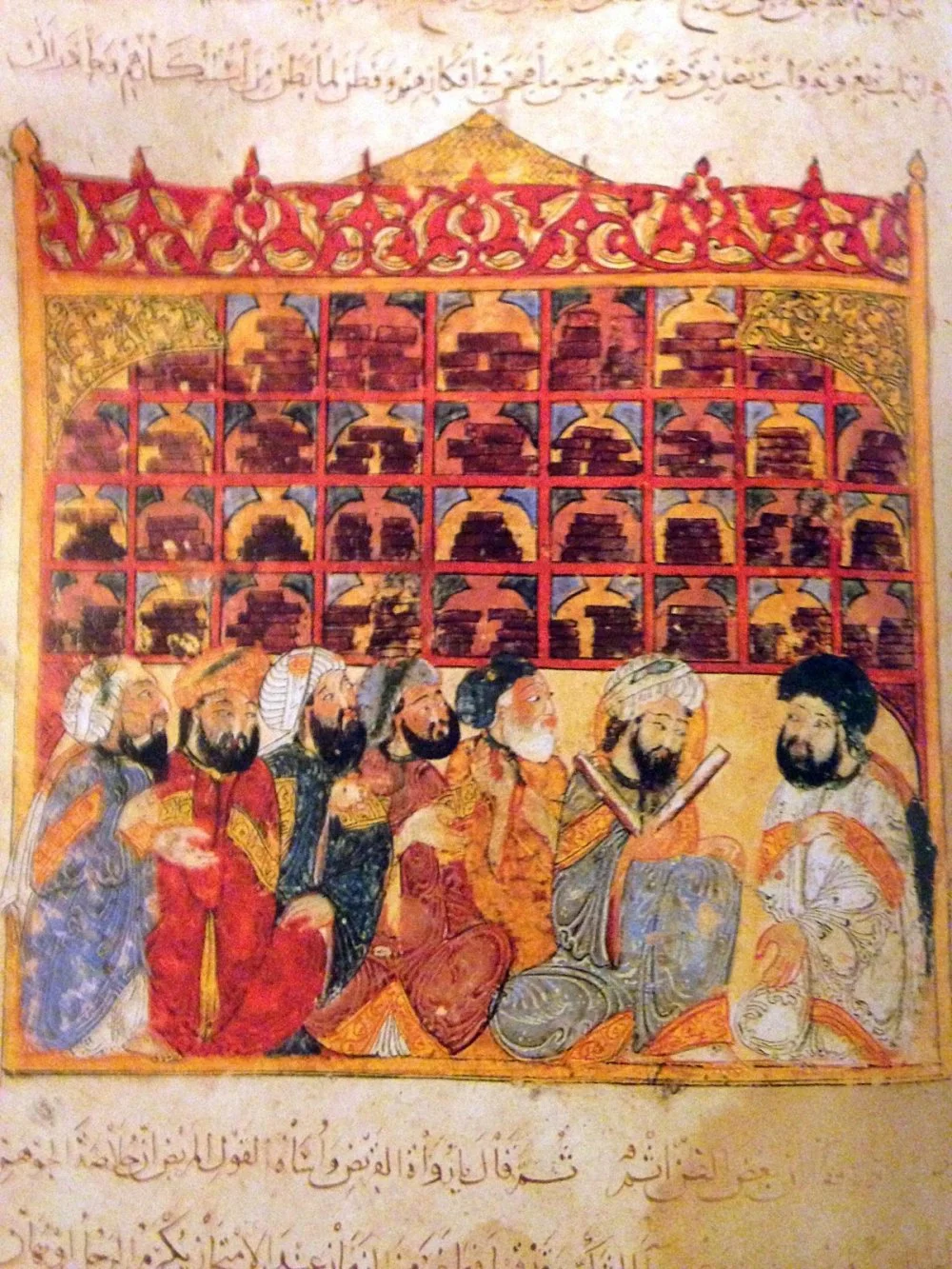

The House of Wisdom

If you enjoy intellectual pursuits, head to the House of Wisdom, which serves as not only a public intellectual hub but a library and an academy as well. Here, you can explore ancient papyri on all kinds of subjects and attend lectures by renowned scholars.

The House of Wisdom in Baghdad, an academy founded in the 9th century by Caliph Al-Ma’mun / Alamy

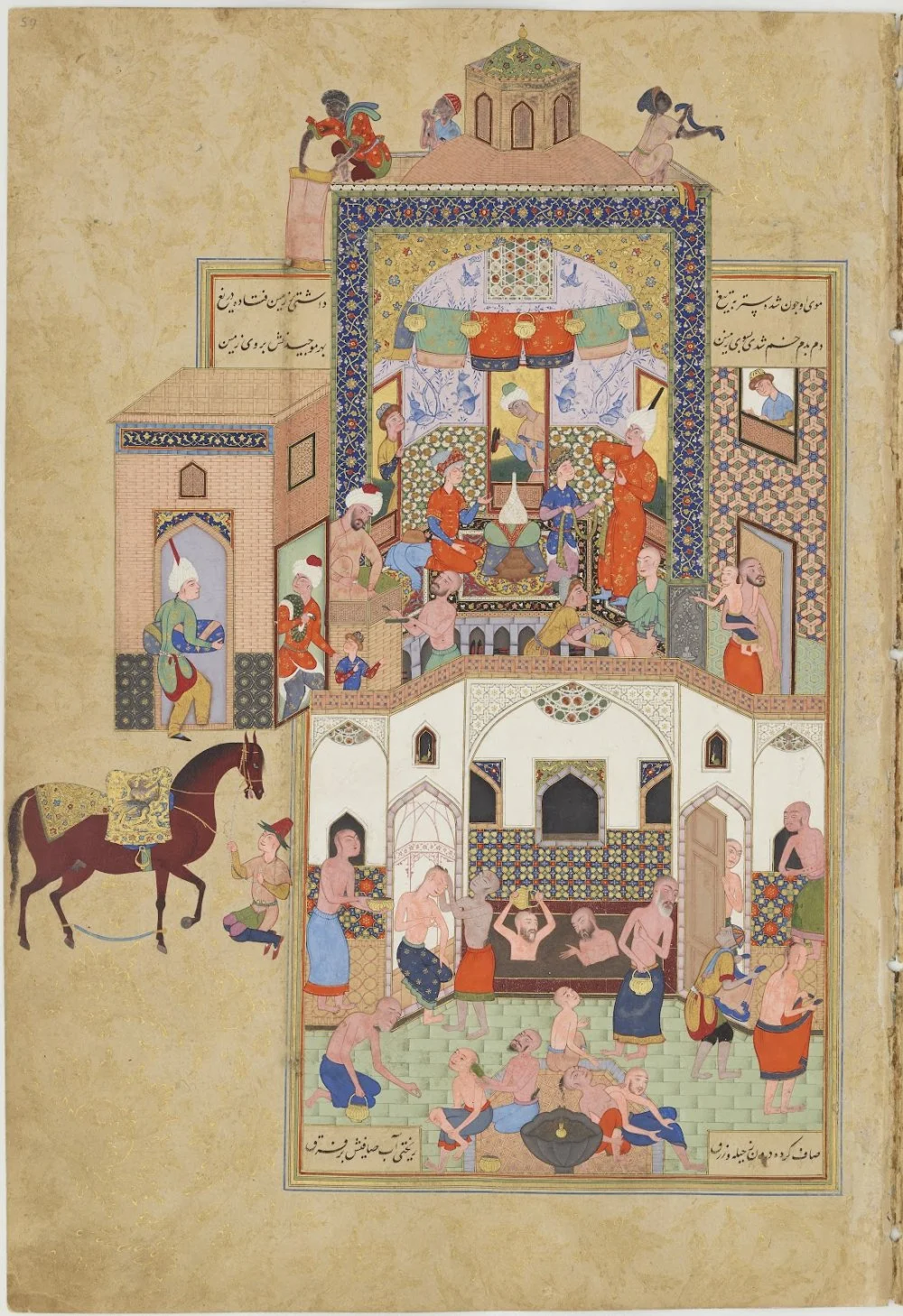

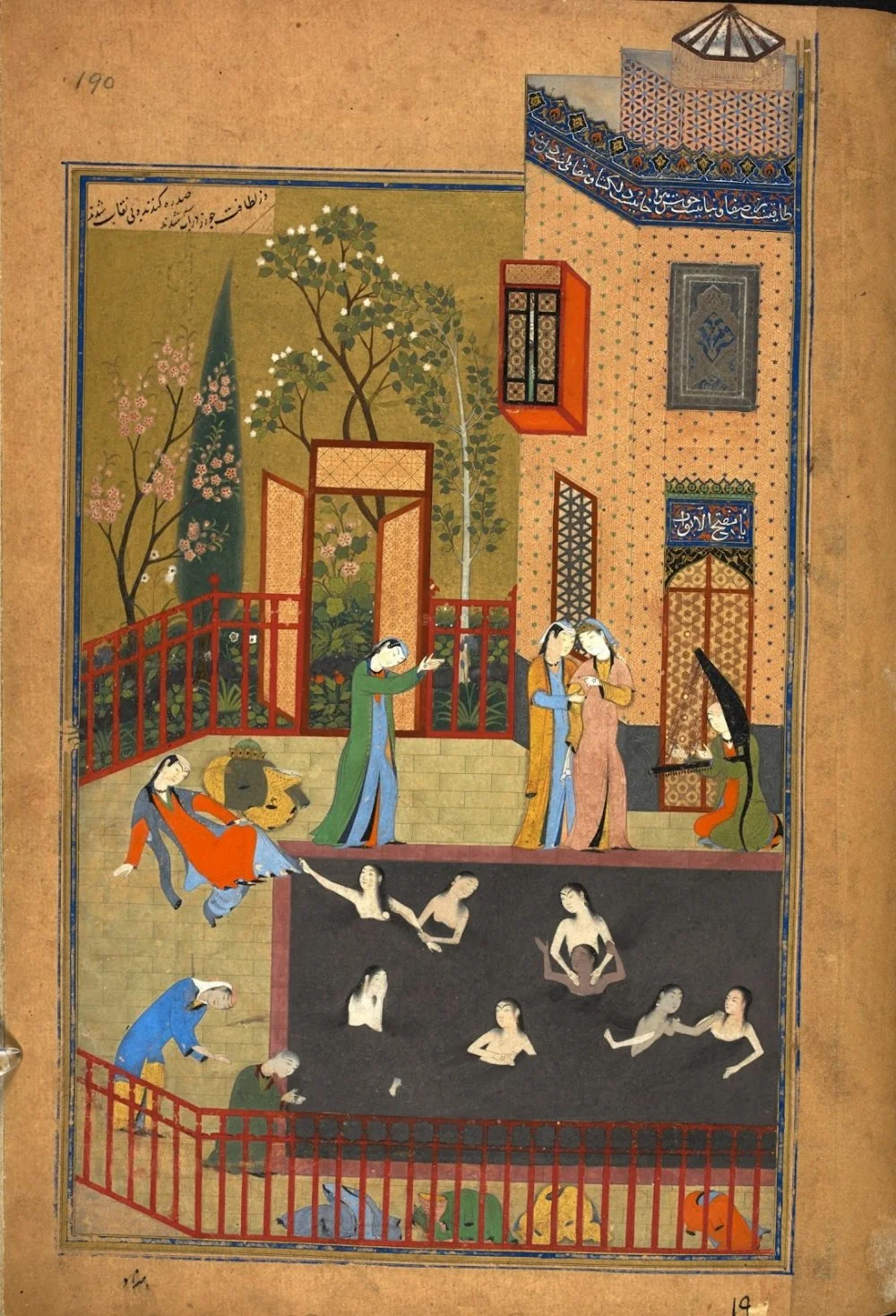

Bathhouses

A visit to a Baghdadi bathhouse is a must. With at least 10,000 bathhouses scattered across both banks of the Tigris, spotting them is easy. On the outside, they are coated with asphalt, sourced from between Kufa and Basra, giving them the elegant appearance of black marble.

The dervish picks up his beloved’s hair from the hammam floor.” Miniature from Safavid Iran, 1556–1565. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution / Wikimedia Commons.

The staff at each bathhouse typically includes a bath attendant, an assistant, a fuel preparer (who burns dried dung for heating), a stoker, and a water carrier. Locals often call these ‘Roman baths’, and they are decorated with frescoes in the Syrian-Hellenistic style. Among the artwork, you might see Al-Anqa, the mythical bird with a human face, an eagle’s beak, four wings, and clawed hands.

Here, you can not only bathe and enjoy some steam but also try a full range of spa treatments, including massages and fragrant body rubs. It’s also a place to relax, dine, and engage in lively conversation.

Bazaars

Don't miss Baghdad's bustling bazaars that are open all day and offer everything imaginable—from Bukharan carpets to Byzantine gold and silverware and the finest Saburian perfumed oils made from ingredients ranging from flowers (violet, lotus, narcissus, dwarf palm, lilies, white jasmine, and myrtle), herbs (marjoram), and fruits (bitter orange peel). You'll also find Frankish and Russian furs on sale here, and the spice, dye, silk, and gemstone markets are clustered together for easy browsing.

John Daniel Revel. The Copper Bazaar, Baghdad. First World War period. Imperial War Museums / Wikimedia Commons

At the bustling bazaars of Baghdad, you can find whatever your heart desires. Fresh fruits are in abundance: apples, pears, and quince are on the pricier side, while olives, dates, apricots, grapes, and peaches vary in price depending on the season. Watermelons, dates, and figs are sold for mere pennies. If you’re in the mood for something out of the ordinary, melons, transported on ice in lead-lined crates, can cost up to 700 dirhams apiece!

And if you should get hungry or perhaps a little thirsty, the bazaars offer more than goods—there are many taverns where you can enjoy slow-roasted meat in a thick sauce, served with fresh flatbreads, a feast for all your senses.

The Flavors of Medieval Markets

Baghdadi cuisine is the perfect balance of simplicity and sophistication. The primary parts of the meal include fresh vegetables, fruits, and stewed or roasted meats, with lamb and poultry being the most common choices. Wheat flatbreads are a staple and are served alongside colocasia (taro root), a tuber somewhat similar to the potato. Pomegranate is added to nearly everything, adding a burst of tangy sweetness to the flavors.

Try the roasted sesame seeds and chestnuts, washed down with sulo, the local version of kumis (fermented mare’s milk). If money is no object, you can also indulge in sturgeon from Lake Van, Spanish tuna, or Egyptian bouri (a traditional Egyptian dish consisting of fermented, salted, and dried gray mullet).

Insider’s tip: To dine like royalty on restaurant-quality food despite being on a budget, head to the gates of the caliph’s harem, where palace chefs sell leftovers from the royal kitchen. And for alcohol, head to the taverns run by the Christians. There won’t be much food—here, wine is considered a dish in itself.

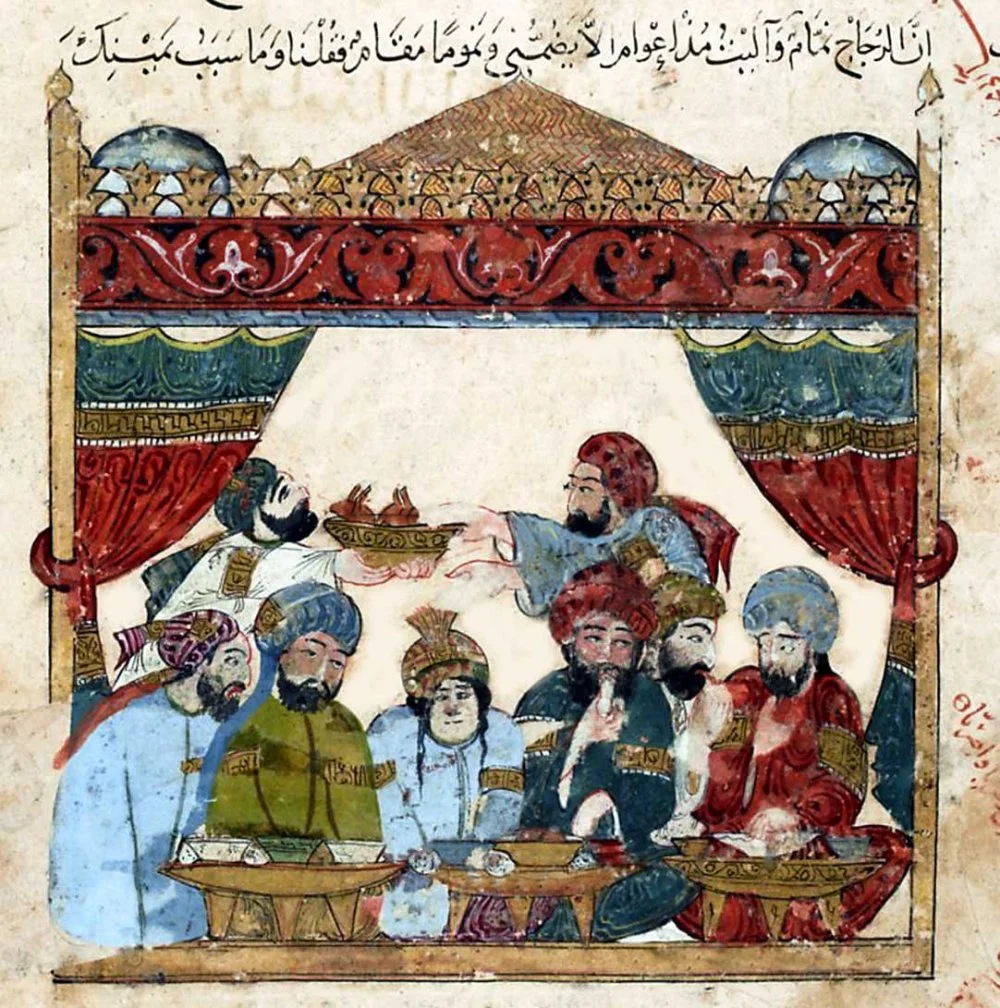

Dining Etiquette

Before the meal, everyone washes their hands in a shared basin, with the host going first. After the meal, hands are washed again, but this time, the host washes theirs last. In wealthy homes, servants pour water over the guests’ hands, provide them with Egyptian linen towels, and sprinkle rose water on their faces.

In a Baghdadi household, the food is served all at once—there is no course-by-course service. Guests choose what to eat and in what order, using the flatbreads instead of plates. The food is usually lightly salted, and in wealthy circles, it is considered mauvais ton—bad form or unacceptable behavior—to add extra salt or vinegar. The same rules apply to eating, and taking large bites and licking one’s fingers are frowned upon.

At the table, etiquette is paramount. Avoid selecting the rarest or most expensive cuts, like brains, liver, eyes, or chicken breast, as it is considered impolite. Using a toothpick at the table is disapproved of—if you absolutely must, make sure you step into the next room .

Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti. Banquet Scene. Illustration from the Maqamat by Abu Muhammad al-Qasim al-Hariri. 1237. Bibliothèque nationale de France, manuscript Arabe 5847 / Wikimedia Commons

Guests are expected to remain reserved during the meal. While the host may speak with guests, they do not expect long responses. The belief is that conversation should complement the meal, not interfere with it.

Ескендір және Сиреналар, 1495–1496 жылдар. Британия кітапханасы, Лондон / Wikimedia Commons

The women of the household do not dine with guests, and asking to meet the host’s wife is a serious breach of etiquette. The only exception to an all-male gathering is a qayna (plural qiyan), a trained courtesan skilled in singing, dancing, and refined conversation.

What to Do If Wine Is Served

Drinking is typically enjoyed in small groups of four or five, and non-drinkers are generally not included in such gatherings. Appetizers are served before the wine, but paying them too much attention is considered rude. After all, the emphasis is on enjoying the company and the drink. Wit is highly valued at the table. Guests tell anecdotes, engage in poetry contests, and invent games. Lighthearted pranks, such as splashing wine on a neighbor, are sometimes part of the fun.

Wine Drinking in a Spring Garden. Miniature, Iran, circa 1430. Opaque watercolor and gold on undyed silk. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York / Wikimedia Commons

Music and dance are essential to Baghdad’s social and cultural life. The qiyan play the lute, flute, or lyre, dance with castanets, and sing. Sometimes, they stay behind a curtain at the beginning of the performance and only reveal themselves if they like the guests. The music can often provoke intense reactions. Some throw themselves to the floor, bite their fingers, or slap their cheeks as a sign of deep admiration, and these displays are not frowned upon.

Women at the table are usually courtesans, slaves, or freewomen invited to the occasion. In the tenth century, Baghdad was home to a famous qayna, a virtuoso lute player, and she had an admirer who wrote her letters begging her to visit him, even if in a dream. She replied: ‘Let him send two dinars, and I will come to him in reality.’

Exploring Ancient Baghdad

By day, Baghdad is a thronging, vibrant city, full of the energy of its markets and merchants, locals and foreigners alike. By night, it comes alive with a plethora of nighttime entertainments, offering everything from lively social gatherings to music and dance.

Go to a Cabaret

Here, you can watch singers, dancers, and musical-dramatic shows. Such a performance is a glimpse into the rich cultural tapestry of the Abbasid era.

Listen to a Tale

At most street corners in the city, storytellers captivate crowds with tales filled with magic, adventure, and moral lessons—much like those that were later compiled into One Thousand and One Nights. Storytelling has become a respected profession in Baghdad, known as al-qassun, a tradition that continues to this day.

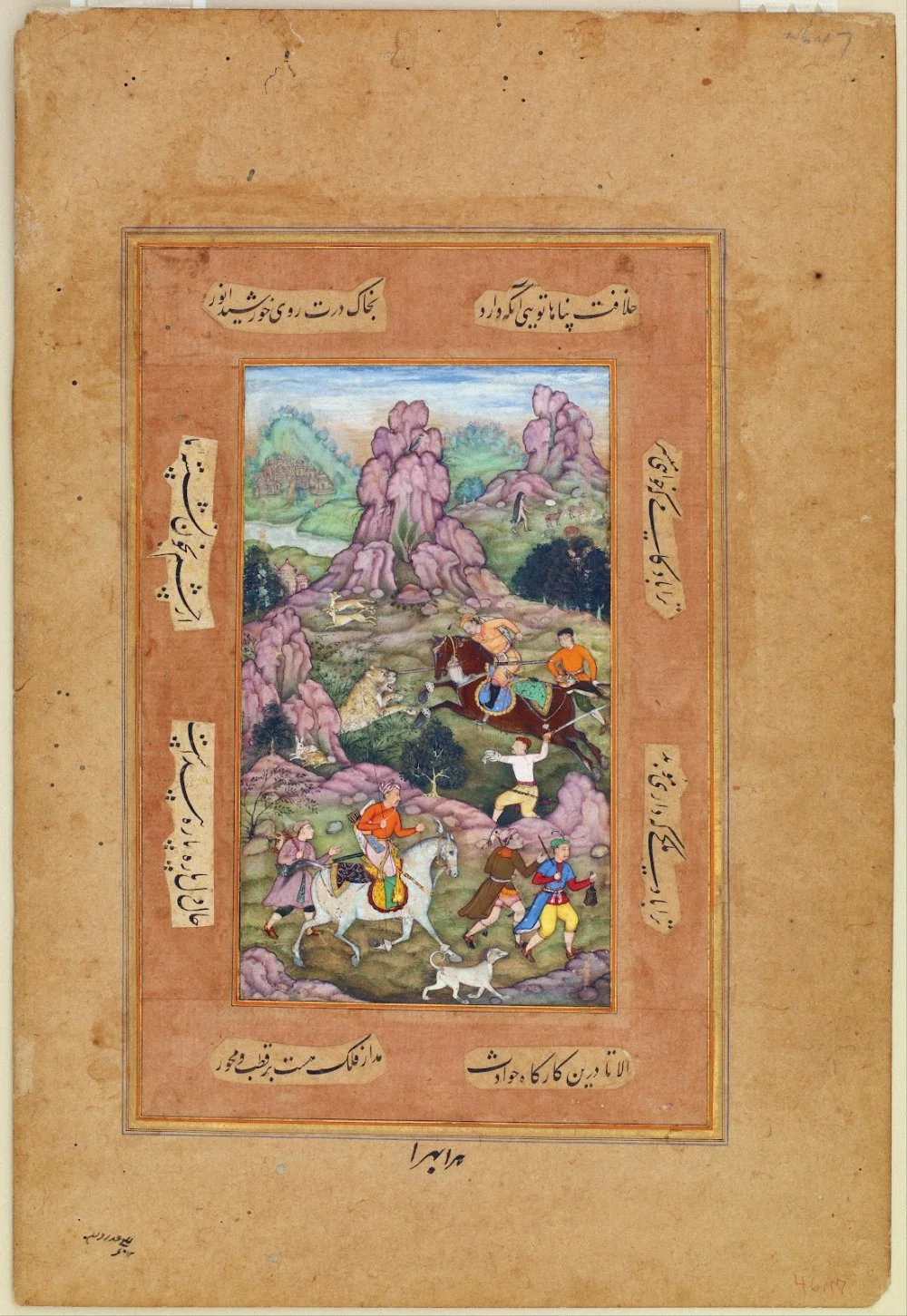

Sports

Polo is a beloved sport played at dedicated hippodromes, where the city’s residents show off their riding skills. But if that’s not your style, you can go on a lion hunt. In Baghdad, even the simplest forms of entertainment, which no one shuns, include cockfights, dogfights, and contests between rams and goats. Among the various forms of gambling, dice games remain popular despite being officially prohibited—a rule that everyone disregards.

A Lion Hunt. Circa 1600. Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution / Wikimedia Commons

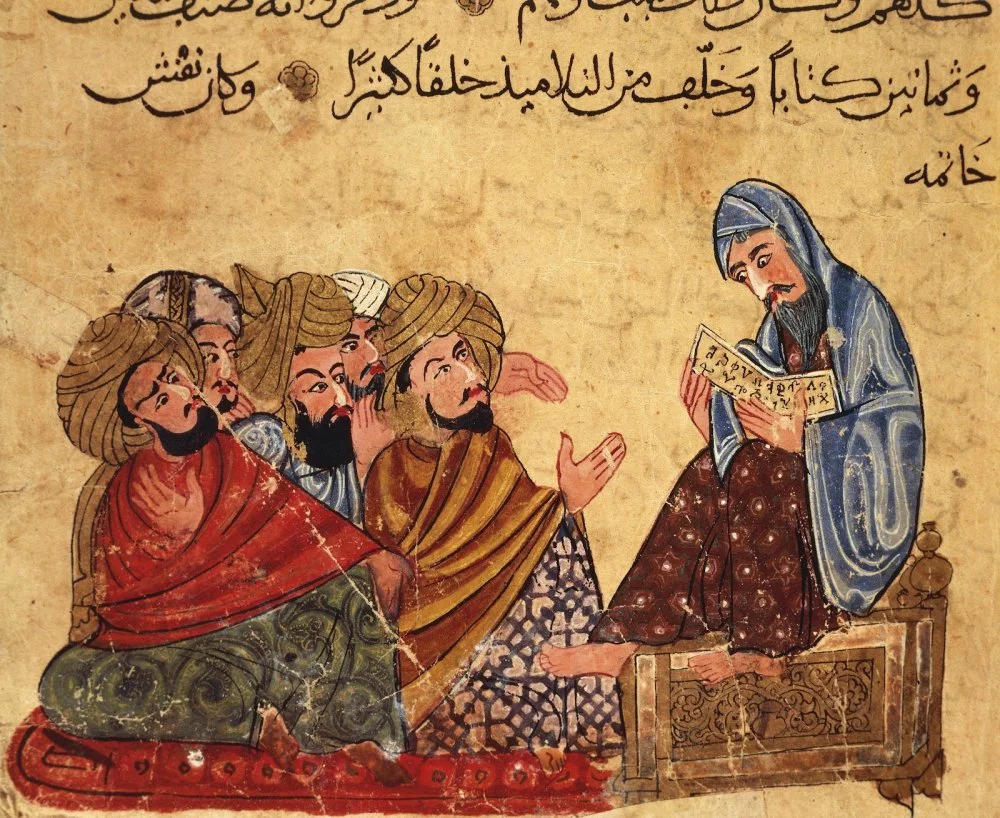

What to Wear in Baghdad

Clothing in Baghdad is essentially unisex, with men and women both wearing a tunic and trousers. When shopping for ready-made garments, remember that bright colors and sharp contrasts are out of fashion in the capital. Some even prefer to dress entirely in white. Avoid black—it is the color of the caliph, courtiers, and officials—and steer clear of purple as it signifies mourning.

A honey-yellow cloak or a tall hat instead of a turban can also serve as a distinguishing feature of a non-Muslim. By the way, everyone wears turbans—men and women, regardless of religion.

Socrates discussing philosophy with his disciples. Arabic miniature from a 13th-century manuscript, Turkey / Getty Images

If you want to appear wealthier, wear two tunics, a robe, trousers in soft color combinations, a fine belt, and elegant shoes. The most prized fabrics include Byzantine satin, fine wool, Dabik white linen, iridescent textiles from Tinnis, and delicate lace-like linen, which is used for cloaks.

Anything Else You Should Keep in Mind?

Blasphemy, grabbing women by the hand, and theft are strictly forbidden. These offenses can quickly land you in prison with a severe punishment—flogging or even the severing of your right hand. Sometimes, a fine may be an option, but you are guaranteed to get in trouble. At night, ensure that you are on your best behavior as the police are on duty even after dark.

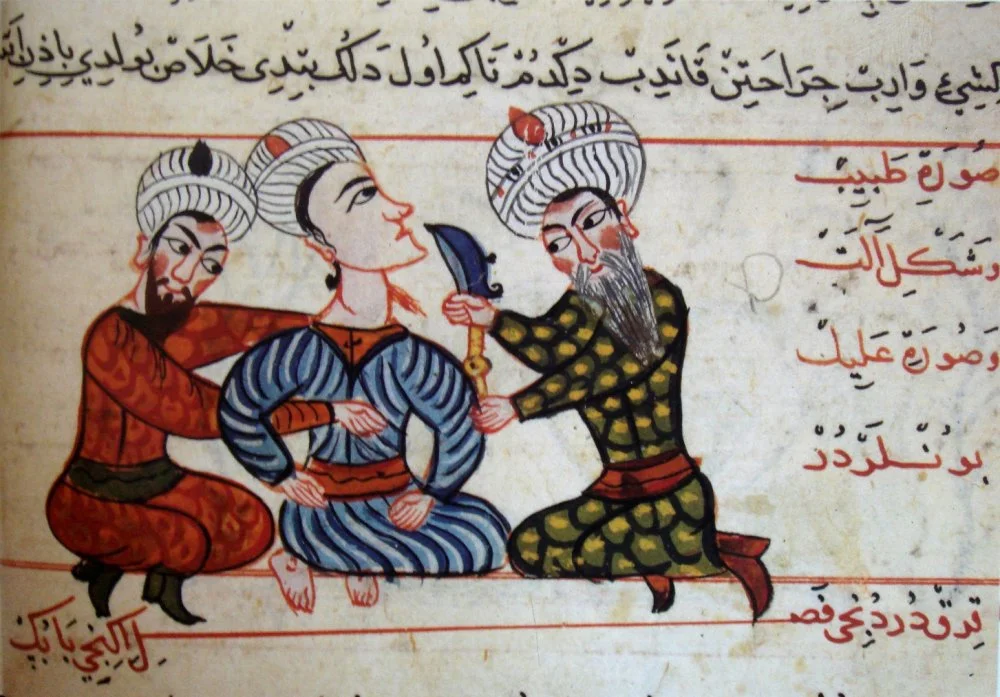

What To Do In Case of a Problem

Unknown artist. Surgical Operation. Illustration from a 15th-century Turkish manuscript/ Wikimedia Commons

If you have been robbed, shortchanged, or wronged in any way, seek out an official immediately—every market and district has one. You can also appeal to the qadi at the main mosque or even file a complaint with the caliph, which is a common practice. Rest assured, your case will be reviewed within a few days, if not immediately (except on Tuesdays and Fridays). The city has numerous law enforcers, judges, and caliphal scribes and, for the most part, they discharge their duties with integrity.

If you happen to fall in Baghdad, there’s nothing to worry about—the city has the finest medical care in the medieval world. Its hospitals are staffed by skilled physicians trained in the latest methods. For example, if you need an abscess drained, the procedure will be done with painkillers and antiseptics. If necessary, you’ll be prescribed a diet, treated for fever, and more. Hospital services are accessible to ordinary people and sometimes even free, thanks to funding by pious benefactors.

Leaving Baghdad

When your journey comes to an end, head to one of Baghdad’s four gates: the Damascus, Kufa, Khorasan, or Basra gate. Built at the city's founding, they have long since crumbled, standing now as symbols of a lost, glorious past, making them the perfect place to begin your journey home.

What to read

1. Al-Tabari. The History of al-Tabari. Volume 29: Al-Mansur and al-Mahdi, A.D. 763–786/A.H. 146–169. Trans. Hugh Kennedy. – Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990. – 172 p.

2. Al-Jahiz. The Book of Misers (Kitab al-Bukhala’). Trans. R. B. Serjeant. – Reading: Garnet Publishing, 1997. – 256 p.

3. Ibn al-Nadim. The Fihrist of al-Nadim: A Tenth-Century Survey of Muslim Culture. Trans. Bayard Dodge. – New York: Columbia University Press, 1970. – 2 vols.

4. Kennedy, H. When Baghdad Ruled the Muslim World: The Rise and Fall of Islam’s Greatest Dynasty. – Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 2005. – 320 p.

5. Gutas, D. Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early Abbasid Society. – London: Routledge, 1998. – 224 p.

6. Bennison, A. K. The Great Caliphs: The Golden Age of the ’Abbasid Empire. – New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009. – 256 p.

7. Lassner, J. The Topography of Baghdad in the Early Middle Ages. – Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1970. – 285 p.

8. Nasr, S. H. Science and Civilization in Islam. – Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006. – 496 p.