Khoja Nasreddin is far more than a character from Kazakh folktales. The stories about him and his span the entire Muslim East—from Turkey and the Balkans to the heart of Central Asia. But is he depicted or understood everywhere in the same ways in which the Kazakhs perceive him? How did Soviet ideology reshape the canonical image of Khoja Nasreddin and what new traits were attributed to him? Finally, who was the legendary Khoja Nasreddin before his tales reached Central Asia? Researcher Assiya Bagdauletkyzy traces the evolution of his image across time and cultures.

The Many Faces of Khoja Nasreddin

In Kazakh folklore, Khoja Nasreddin, known as Qojanasyr, is at once a clever trickster, an ironic sage, and a kind-hearted eccentric. His short anecdotes may appear to be simple jokes at first glance, but within Kazakh culture, this character—who arrived along with Islam—has largely lost his original religious undertones. In contrast to other regions, our Nasreddin is, above all, a virtuoso of language and sharp wit. Through humor, he exposes the vices and contradictions of human nature, becoming, in essence, a vehicle for social critique and reflection on life.

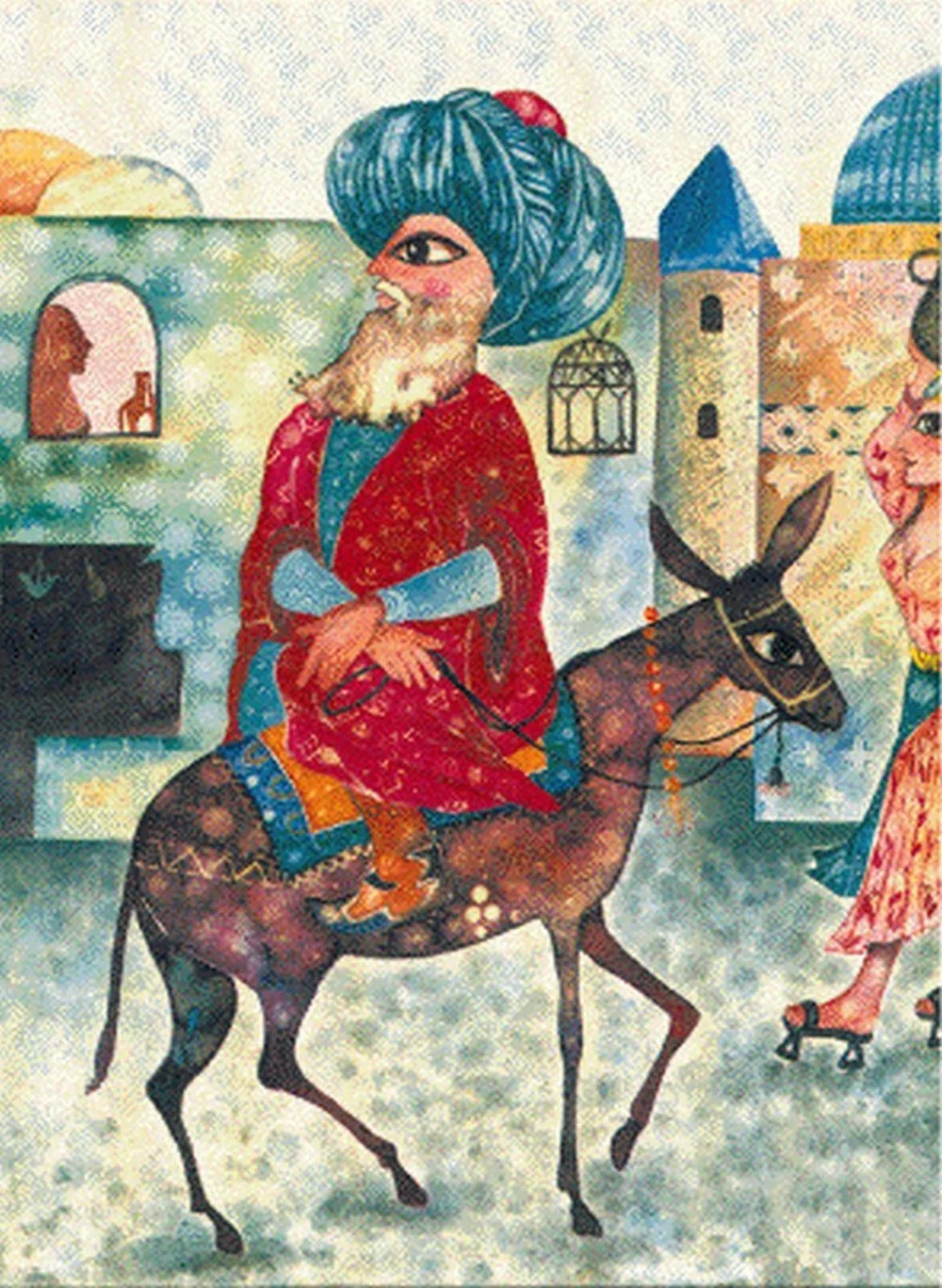

Nasreddin Khoja / Alamy

In Soviet iconography, Nasreddin is depicted as a lean man, young or middle-aged, a defender of the poor, and a figure of humble origins. Films and animated features produced in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR)i

The Turkish Nasreddin looks entirely different. Indeed, he was a venerable old man with a gray beard and an enormous turban. Judging by his clothing, he was a well-to-do person, and his turban seemed almost larger than his little donkey. Though the presence of such contradictory traits in a single character might seem coincidental, research suggests that Khoja Nasreddin conceals many more mysteries we have yet to uncover.

Monument to Khoja Nasreddin in Bukhara, Uzbekistan / Getty Images

In Arab culture, this character is known as Juha (Jokha or Gurha). According to scholarly research, this image emerged even before Khoja Nasreddin himself, and over time, the two well-known figures of the Islamic world became intertwined. In Iran and Afghanistan, he is known as Mulla Nasreddin. The character also gained wide popularity in the Balkan Peninsula under the influence of the Ottoman Empire, where he, similarly, appears as a man of the people.

According to folklorist Ulrich Marzolphi

In renowned academician Abduselam Arvas’s interpretation, Khoja Nasreddin exemplifies the transformation of a ‘pseudo-historical’ figure with a vague past into a folkloric archetypei

And for this reason, studies of Nasreddin generally fall into two main approaches: the first is national-historiographical, primarily Turkish, while the second is international and folkloristic, where questions of whether he actually lived and how many stories originally belonged to him are treated as secondary.

Monument to Khoja Nasreddin in Yenişehir, Turkey / Alamy

To begin with, let us focus on the image of Khoja Nasreddin in Turkey. Folklorist Jo Ann Conradi

Khoja Nasreddin: The History of an Image

Stories about Khoja Nasreddin have existed for centuries in oral tradition. Systematic documentation in written sources did not begin until after 1571, signaling the transition from oral transmission to the written word. One of the earliest such sources, a manuscript titled Hikayat-i Kitab-i Nasreddin Hoca, contains forty-three stories about him. In most of them, Nasreddin bears little resemblance to the image that is familiar to us today. It is clear that the character’s transformation over the centuries resulted not only from shifts in cultural norms and moral values but also from the tangible influence of various political and power dynamics.

In the earliest literary versions, Khoja Nasreddin appears as a figure who does not submit to rules and exists outside social norms. He is seen as a kind of ‘rascal’ who openly flouts religious prescriptions and rituals. And thus, in these narratives, he often comes across as a vulgar character who deliberately violates taboosi

Khoja Nasreddin. 17th-century miniature / Wikimedia Commons

The evolution of Khoja Nasreddin’s persona is especially evident during the Ottoman period. It was then that he gradually became ‘socialized’—he married, had children, and was integrated into the state religious project, turning into a representative of Sunni orthodoxy. Over time, his former freedom and indecency faded away. He aged, assuming the appearance of a humble and pious aqsaqal, or village elder. Thus, the transformation of Nasreddin in Turkey from a ‘naughty rascal’ into a wise national symbol was the result of deliberate ideological adaptation.

The Soviet Khoja Nasreddin

In Central Asia, the dominance of oral tradition makes it hard to pinpoint exactly when and how the image of Khoja Nasreddin took hold. By the early nineteenth century, however, he had already assumed a ‘sanitized’ form because he was stripped of indecent or rebellious traits, and he appeared as a safe, elderly figure. All the same, he remained quite different from the Ottoman Nasreddin. In Central Asian folklore, he is a free spirit, existing outside social conventions; a man whose family is seldom mentioned. He is an eternal wanderer on a donkey, bound by neither class nor ethnic boundaries.

In the Soviet era, this beloved folk character—a bearer of multilayered cultural capital—was recreated as a modern socialist hero. The Soviet Khoja Nasreddin was portrayed as a ‘proto-socialist’—he opposed feudal injustice and defended the poor. Promoting such an image was an attempt to culturally ‘legitimize’ socialist ideology, grounded in the idea of class struggle, among the Muslim peoples of Central Asia.

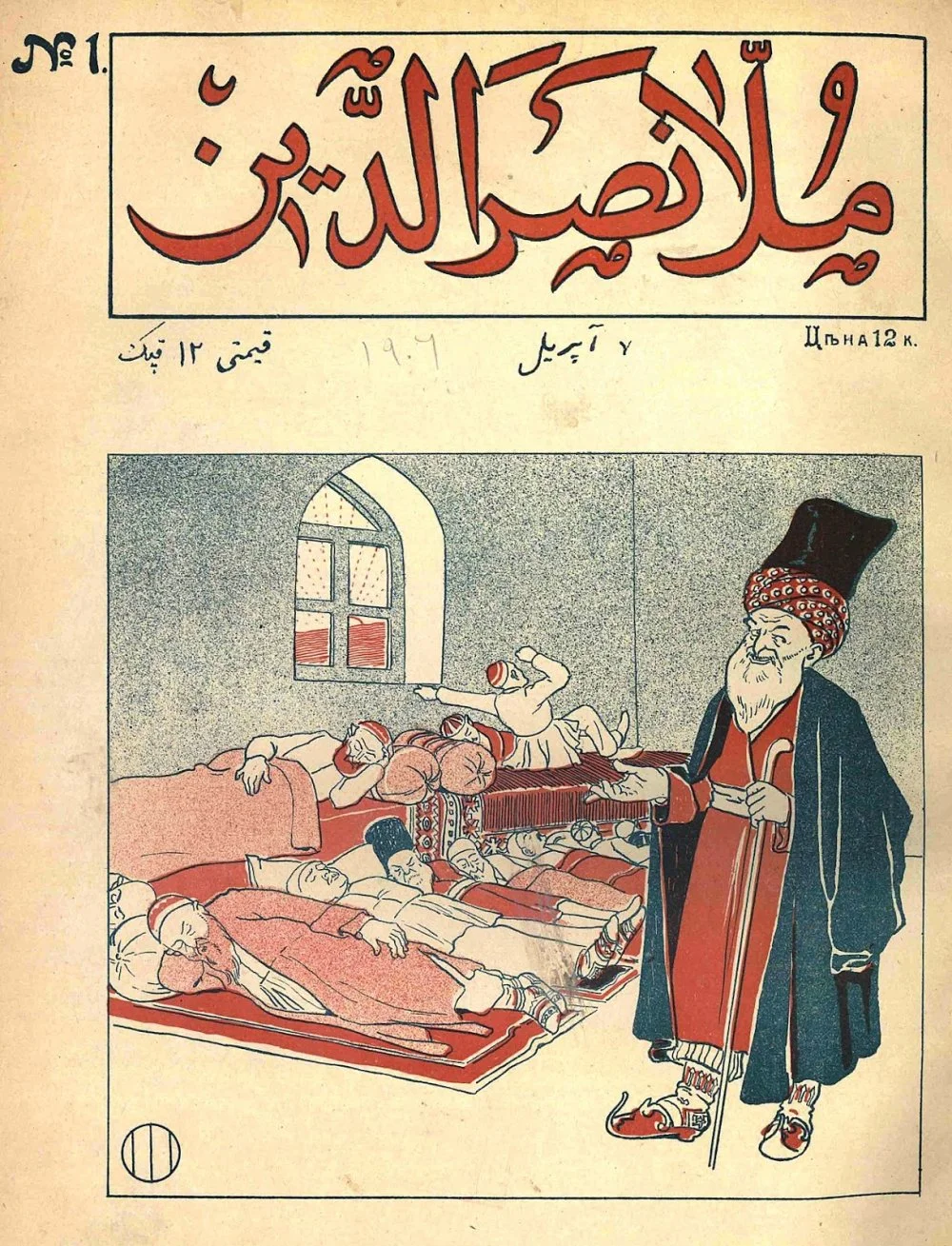

Cover of the first issue of the Azerbaijani satirical magazine Molla Nasreddin, depicting Khoja Nasreddin, 1906 / From open sources

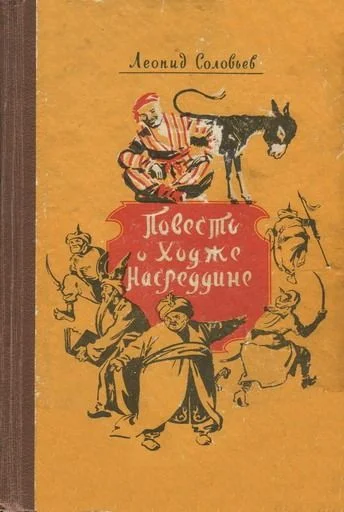

The first person to make this character famous throughout the Soviet Union was journalist and writer Leonid Solovyovi

Between 1923 and 1930, Leonid Solovyov worked for the Uzbek newspaper Pravda Vostoka, where he started collecting and recording local folklore. Although these experiences later inspired a screenplay, the project was not realized at the time and remained shelved for many years. Nasreddin’s moment of glory in the Russian-speaking world came in 1940, when Solovyov reworked the accumulated material and wrote the novel The Disturber of the Peacei

Leonid Solovyov / From open sources

At the end of 1941, when Soviet film production was evacuated to Central Asia, director Mikhail Rommi

Thus, the film Nasreddin in Bukhara went into production and was shot in 1943 at the Tashkent Film Studio. Notably, all the principal roles—Nasreddin himself, the Emir of Bukhara, Niyaz, the vizier, and other characters—were played by Soviet actors ‘of European origin’ who had come from the center. And from this moment on, the process of visually Sovietizing the image of Khoja Nasreddin began.

Nasreddin—But Not Quite the Same

At the time, the newspaper Pravda noted that ‘the return of Nasreddin to the screen will undoubtedly arouse special interest among kindred audiences in the national republics’. However, the paper did not go into detail about how exactly the image, so familiar to this very ‘kindred audience’, had been transformed under the influence of Soviet ideology.

In the folklore of the Soviet East, Nasreddin was traditionally addressed with reverence, including hodja (teacher), efendi (master), and mulla (cleric). In Azerbaijan, for example, the word ‘mulla’ denoted not only a religious status but also such qualities as education, competence, and life experience. In Central Asia, the terms ‘hodja’ or ‘hajji’ indicated both social and spiritual standing as well as the fulfillment of the hajj, or the religious duty of pilgrimage, while the very name ‘Nasreddin’ (Nasr ad-Din) literally meant ‘victory of the faith’. However, in Soviet literary and cinematic representations, these religious and spiritual layers were completely erased.

A Disturber of the Peace?

To answer this question, let us first turn to Solovyov’s novel. It is important to bear in mind that the views of Soviet writers from the European part of the country toward Central Asia were largely shaped by an orientalist tradition rooted in tsarist Russia's imperial discourse. And Solovyov was no exception. Scholarly literature has repeatedly noted that his work—especially his short prose—relied on orientalist modelsi

Soviet orientalism sought not only to exoticize the region and emphasize its ‘otherness’, but also to present Central Asia, prior to its conquest by the Russian Empire, as a backward, stagnant land. In the novel The Disturber of the Peace, this is particularly evident. On the one hand, Bukhara is transformed into an exotic backdrop, while on the other, local society is portrayed as a symbol of feudal stagnation. The proto-socialist Khoja Nasreddin comes to the rescue of this ‘decayed’ state. Thus, one can, in fact, discern Soviet power itself hiding behind the figure of Nasreddin in the novel.

Leonid Solovyov, The Tale of Khoja Nasreddin. Molodaya Gvardiya Publishing House, 1957. Illustrated by Stanislav Zabaluev / From open sources

There is an opinion that through the image of Khoja Nasreddin, Solovyov was criticizing Stalinist power. However, in both his novel and Protazanov’s film, the ‘disturbed peace’ is clearly not the peace of Soviet authority but that of the emir. Viewed in this light, Solovyov’s work is much closer to the leader’s discourse on ‘Asian backwardness’ than to any subtle act of resistance.

Rather than opposing Soviet ideology, he reinforced its positions, employing satire easily understood by a broad audience and cloaked in orientalist imagery. This is precisely why the novel about Khoja Nasreddin became a convenient instrument of cultural control and symbolic class division.

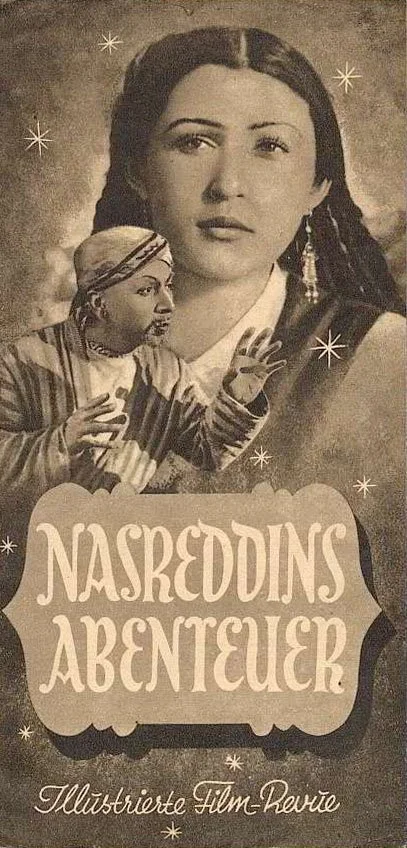

Poster for the film The Adventures of Nasreddin / Wikimedia Commons

While Solovyov’s first work, written jointly with Vitkovich, was still in the process of being adapted for the screen at the Tashkent studio, its sequel was already being created. Although the second screenplay was also intended for Yakov Protazanov, it ultimately went to the Uzbek director Nabi Ganievi

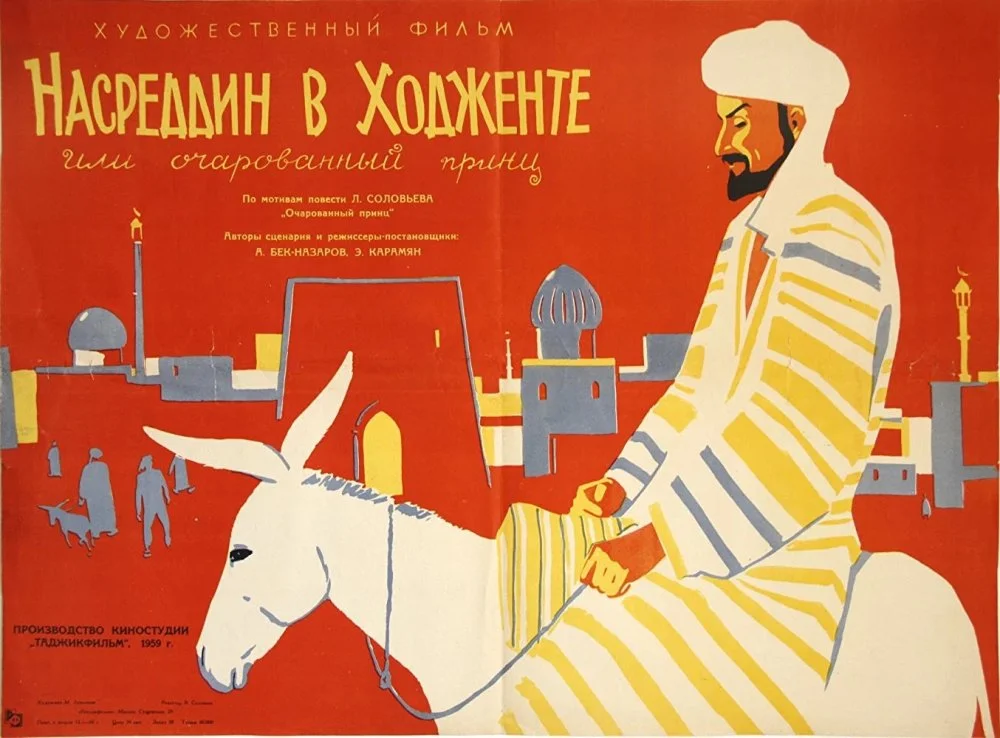

And Solovyov did not stop there. In 1954, he published the novel The Enchanted Prince, a sequel to The Disturber of the Peace, which served as the basis for another feature-length film produced in 1959 at the Tajikfilmi

In this context, Kazakhfilm’s interest in the character of Aldar Kose during the 1940s and 1950s—largely modeled on the same framework as the Soviet image of Nasreddin—can be seen as a continuation of the trajectory established by Solovyov.

Khoja Nasreddin—the Agitator

As scholars note, the Soviet interpretation of Khoja Nasreddin presented him as a ‘jovial jester’, deliberately stripped of Islamic elements and safely incorporated into the unofficial Soviet racial hierarchyi

In the film, Nasreddin falls in love with the daughter of a poor man and rescues her from the emir, who had placed her in his harem. This kind of plotline adapts Nasreddin's image to Soviet (and, to some extent, Western) narrative standards, ultimately distancing him from his original folk persona.

The Adventures of Nasreddin, 1946. Directed by Nabi Ganiev / From open sources

The excessive politicization of Khoja Nasreddin’s image is especially evident in his dialogues. In one scene, a poor man rescued from debt offers him a share of his earnings, to which Nasreddin replies: ‘If all masters shared their profits with their workers, what would become of this world? Would Allah or the emir tolerate such disorder?’

By portraying religious and traditional authority as a source of injustice, he becomes an agitator, giving the impression of a man ‘ready to join the ranks of the Communist Party’.

From Oral Tradition to the Silver Screen Hero

After this film, Soviet cinema repeatedly returned to the image of Khoja Nasreddin. In some works, he was overtly ‘colored’ in the spirit of socialist realism, while in others, more profound meanings and elements of social critique emerged. In 1946, at the Tashkent Film Studio, Nabi Ganiev directed The Adventures of Nasreddin, a sequel to the previous film. Razzak Khamraev, the celebrated Uzbek Soviet actor playing Nasreddin, appeared more convincing than Lev Sverdlini

In the cinematic fairy tale Nasreddin in Khujand, or The Enchanted Princei

Uzbek Soviet actor and film director Mukhtar Aga-Mirzaev’s film The Twelve Graves of Khoja Nasreddini

In 1975, Soviet film and television director Pavel Arsenov’s musical fairy-tale film The Taste of Halvai

Finally, during the Perestroika era, actor Anatoly Bobrovsky in The Return of Khoja Nasreddini

Poster for the film Nasreddin in Khujand, or The Enchanted Prince / Kinopoisk

Ultimately, during the Soviet period, Khoja Nasreddin transformed from a character of oral tradition into a frequent figure on the silver screen. His cinematic adaptations and visual portrayals represented an attempt to harness and control folklore. From 1943 onward, clad in a ‘Soviet chapan’ and cast as a defender of the poor, the screen version of Nasreddin remained loyal to socialist ideals throughout the Soviet era, evolving from a young, cheerful character into a thoughtful, critically minded sage.

Yet, the Soviet authorities never fully controlled this figure. In many instances, Nasreddin became a critic of Soviet reality himself, and as a ‘composite character’, he continued to evolve with the times, acquiring new stories and meanings. Nevertheless, because his image was most often adapted by directors from the ‘European’ regions of the Soviet Union, Nasreddin invariably retained the hallmarks of the stereotypical face of Soviet Orientalism.