Back in ancient times, money didn’t always take the form of coins, much less the paper money we use now. Back then, it was quite acceptable to pay people in blocks of salt.

Salt has always been a highly prized commodity, even among coastal communities, often serving as a form of currency. Today, if you were to assume that the process of obtaining salt is a straightforward one—simply put seawater in a pot, evaporate it and voila!—you would be surprised to find that this process yields a salt with an unpleasant residue. It is more bitter and soapy in taste than salty, mainly consisting of dissolved organic matter and sand.

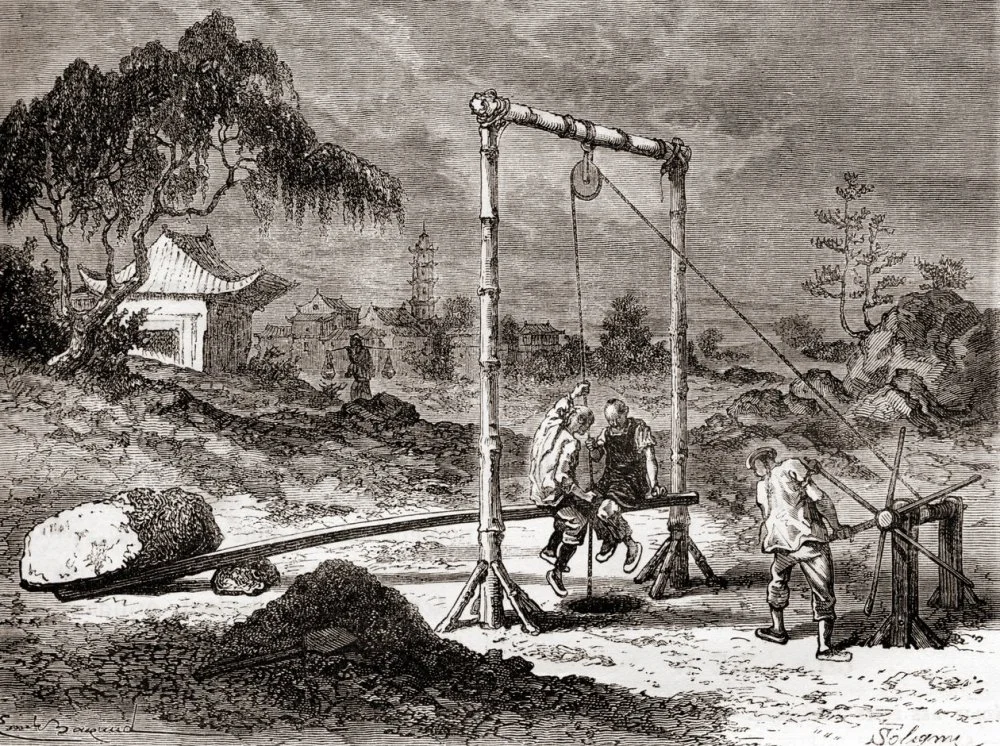

Evaporating seawater is quite an intricate undertaking and today, ‘natural sea salt’ is obtained through a natural evaporation process using cascading ponds. However, in ancient times, evaporation through heating and filtration incurred immense costs. It involved a complex, multi-stage process that used a substantial amount of expensive fuel. The resulting salt would have been as valuable as gold.

Chinese workers in the 19th century digging a well for the extraction of salt water/Ken Welsh/Getty Images

Ancient civilizations relied on rock salt, which was relatively scarce. It held significant value as a resource and commodity and was often controlled by a state monopoly. Private salt extraction was prohibited in both ancient China and ancient Rome.

In China, for instance, ‘salt money’ was very much in use—people were paid in solid blocks of pressed salt stamped with official seals. The compensation for a Chinese official often comprised money and bundles of silk, bags of rice, and blocks of salt. In The Travels of Marco Polo, the famous traveler describes salt as: ‘Their currency is distinctive: they possess gold in bars ... and the smaller denominations are fashioned differently: they take salt, boil it, and shape it into pieces weighing about half a pound each; eighty of these pieces are equivalent to one unit of pure gold. This constitutes their minor currency.’

Salt currency from Ethiopia, found in 1925/The Trustees of the British Museum

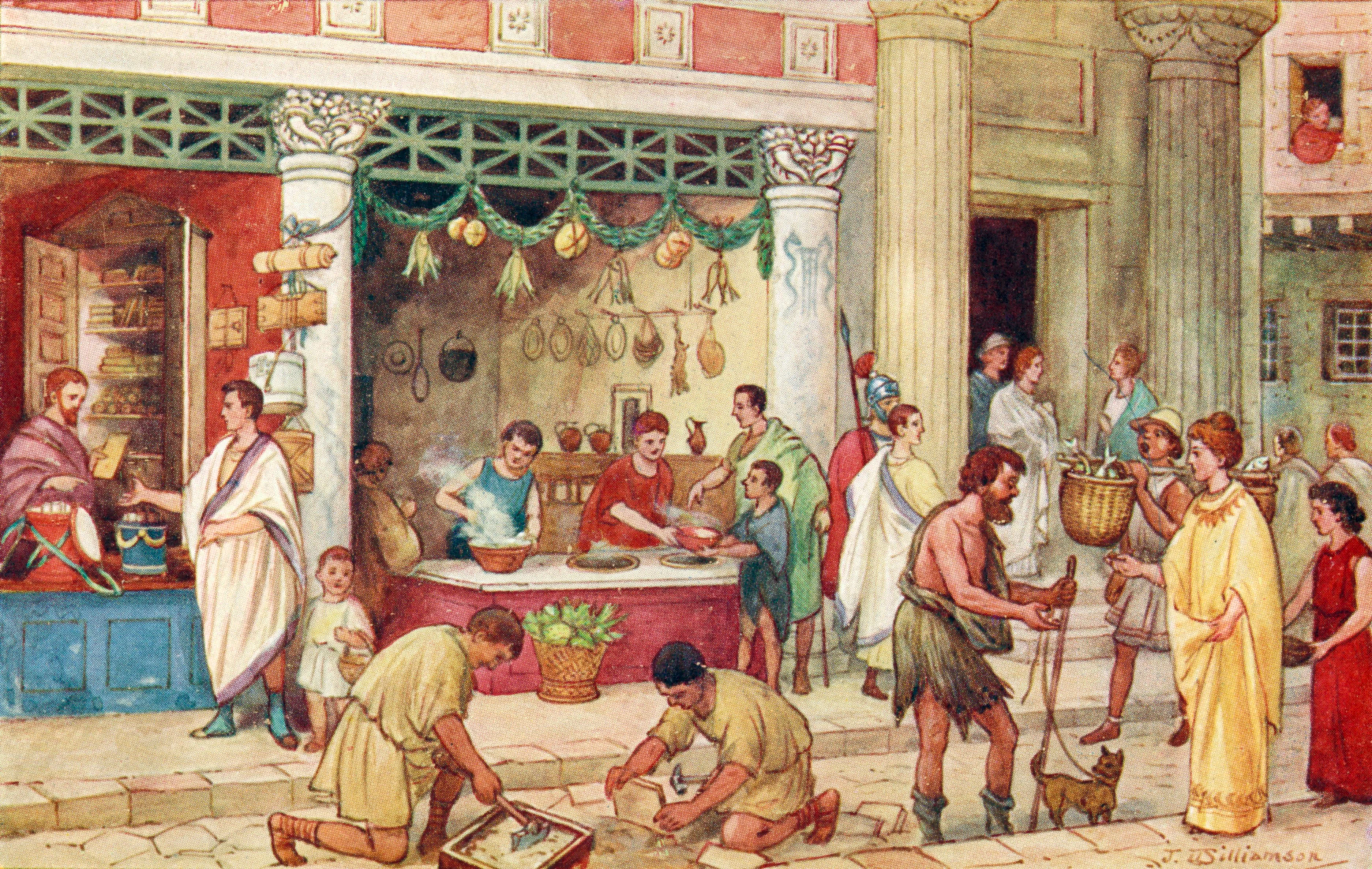

In ancient Rome, salt was made at the mouth of the Tiber, where significant salt deposits were found. The monopoly on extraction belonged to the state, and it was such a widely traded commodity that it was often used as currency. For instance, Roman soldiers received part of their wages in salt. While legionnaires also received monetary payments and other forms of compensation, the salt allowances soon became synonymous with their ‘military salary’. In fact, the English word ‘salary’, meaning ‘payment for work’, is derived from the Latin word sal meaning ‘salt’.

The word ‘soldier’ originates from the medieval term soldi, which refers to a small coin that can be traced back to the Roman solidus (Latin for ‘solid’). Armies that formed the centralized monarchies of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Europe were composed of mercenaries who received solid payment in forms other than salt.

Solidus of Theodosius II, minted in Constantinople. About 435 years/Wikimedia Commons

What to read

Polo, Marco. 2021. The Travels of Marco Polo. Palmyra.