From the middle of the twelfth century, Europeans believed that somewhere in the East, in the territory of either Kazakhstan or India, there was a vast Christian kingdom ruled by a king and priest called Prester John.

During the First Crusade (1096–99), Christians waged war to conquer the Holy Land from Muslims and establish their own states in Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria. However, by the middle of the twelfth century, Muslim forces started attacking the Crusader states more often and with more force. The first to fall was Christian Edessa,i

‘I am John, king and priest, king over kings. There are 3,300 kings under my rule. I am a champion of the Orthodox faith of Christ. My kingdom is like this: on one road you must travel for ten months, and it is impossible to reach the other, because heaven and earth meet there.’

From Legends of the Indian Kingdom, in the Ephrosin Belozersky manuscripts (fifteenth century)

Nestorian priests in a procession on Palm Sunday, in a seventh- or eighth-century wall painting from a Nestorian church in Qocho, China/Wikimedia commons

For nearly 500 years, Presteri

The First Narrator: Bishop Hugh of Syria

The first mention of Prester John is found in the book Two Cities—A Chronicle of Universal History to the Year 1146 A.D.i

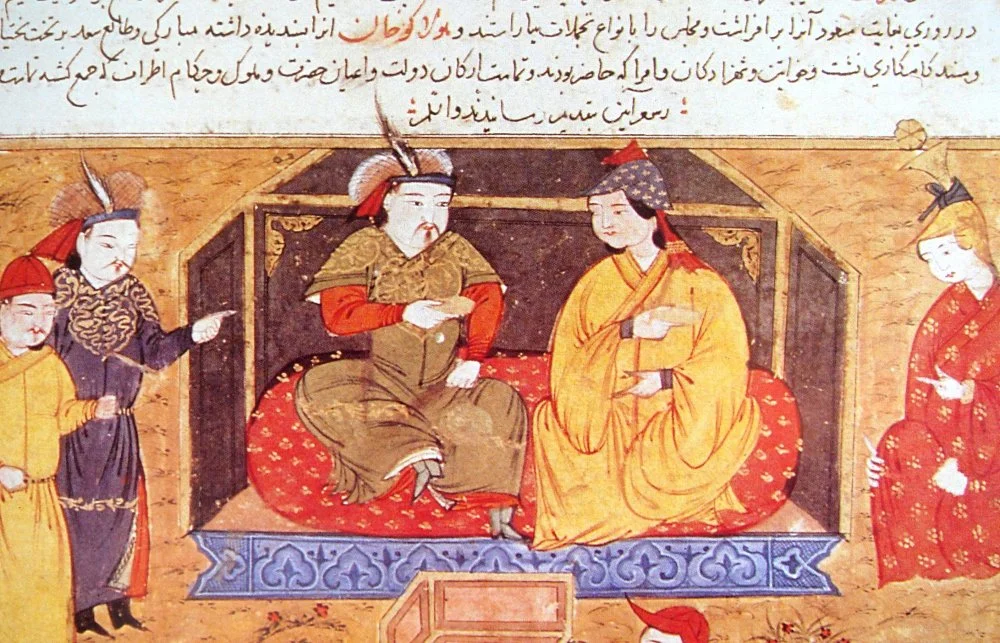

Depiction of the Keraite ruler Toghrul as "Prester John" in "Le Livre des Merveilles", 15th century/Wikimedia commons

… He said, indeed, that not many years since, one John, a king and priest living in the far east, beyond Persia and Armenia, and who, with his people, is a Christian, but a Nestorian, had warred upon the so-called Samiards, the brother kings of the Medes and Persians. John also attacked Ebactana, the capital of their kingdom. When the aforesaid kings advanced against him with a force of Persians, Medes, and Assyrians, a three-day struggle ensued since both sides were willing to die rather than to flee. At length, Prester John, so he is usually called, put the Persians to flight and emerged from the dreadful slaughter as victor. The bishop said that the aforesaid John moved his army to aid the Church of Jerusalem, but that when he came to the Tigris and was unable to take his army across it by any means, he turned aside to the north, where he had been informed that the stream was frozen solid during the winter. There, he awaited the ice for several years, but saw none because of the temperate weather. His army lost many men on account of the weather to which they were unaccustomed, and he was compelled to return home.

From Two Cities—A Chronicle of Universal History to the Year 1146 A.D. by Otto of Freising

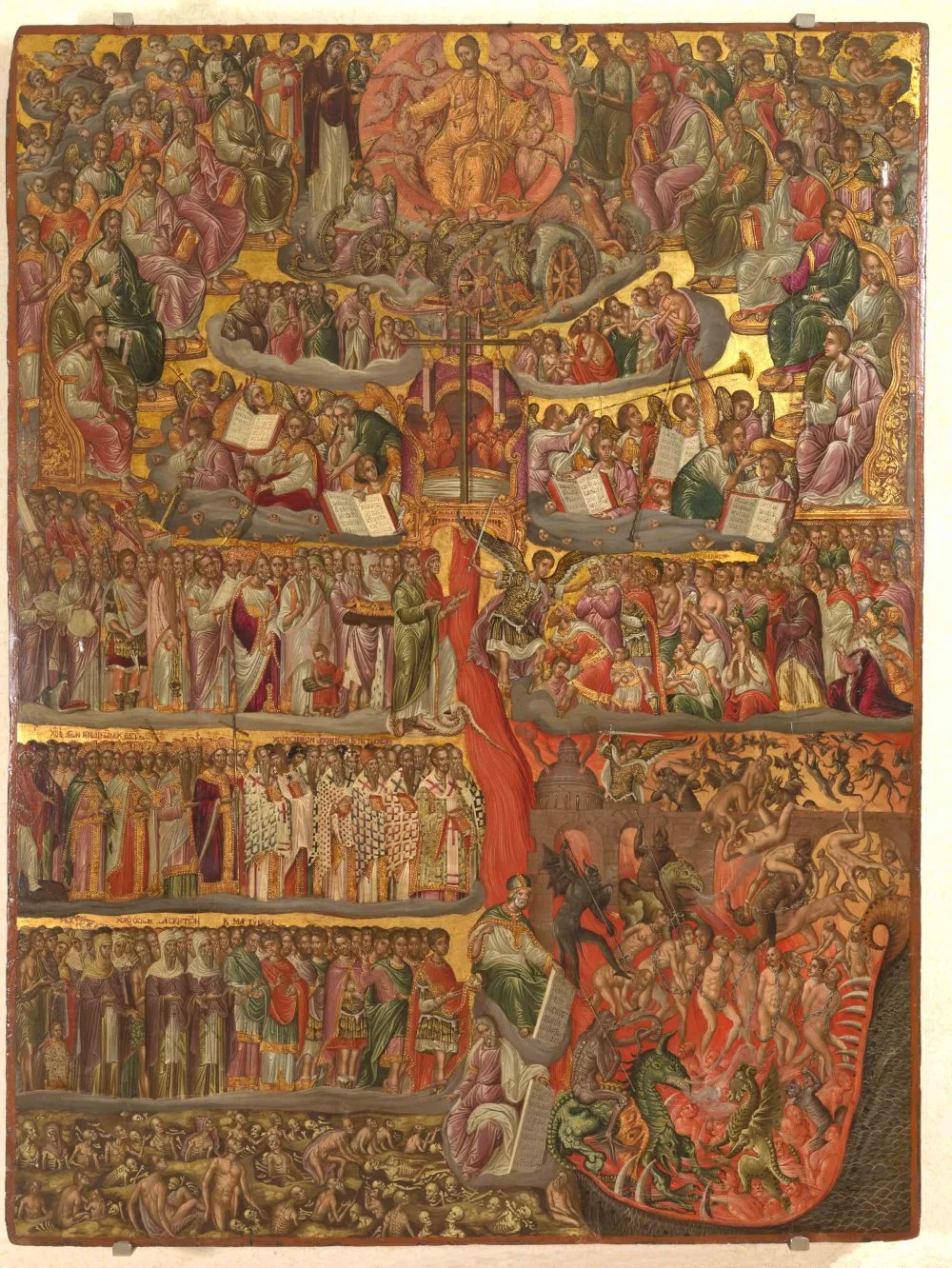

Awaiting the Realm of Spirit

For a long time, people in different cultures did not think much about the future. They thought either of the mythological past, populated by gods and heroes, or of the present, with its cyclical change of seasons. The idea of thinking about the future (which we now call futurology) first began to develop in Christianity. Christians believed that the end of history was known and described in one of the books of holy Scripture, the Revelation of St John the Divine, also known as the Apocalypse. Jesus will return to Earth to administer the Last Judgment. The search for signs of the inevitable and imminent end of the world was a favorite theme of medieval mystics, quite like how various analysts, prophets, and Hollywood directors nowadays love to frighten the world with the prospect of a coming catastrophe. In the twelfth century, the teachings of the Italian monk Joachim of Fiore (died 1202), who predicted the imminent arrival of the millennial kingdom of God on earth, became extremely popular. This kingdom of the spirit would be ruled by priests like Prester John.

The Scion of the Magi

The name ‘John’ had come up previously in conversations about the Christian East. In 1129, the Patriarch of the Indies (Patriarcha Indorum) named John traveled from Baghdad to India on a Christian mission. It is likely that the same missionary visited Constantinople and Rome in 1122, during the pontificate of Callixtus II, as recorded in the chronicle of Aubry de Trois-Fontaines written in the 1250s. The same chronicle also mentions the spread of Nestorian Christianity and the tomb of the Apostle Thomas in the Indian village of Mailapura.

Renaissance map of Europe, Jacopo Russo, 1528, detail showing Prester John/Alamy

In general, it was easy for people in the twelfth century to believe in the existence of the Christian Empire in the East. After all, the biblical Magi, called ‘kings’ in the Latin tradition, came from the same direction to greet the newborn Jesus.

He is said to be a descendant of the Magi of old, who are mentioned in the Gospel. He governs the same people as they did and is said to enjoy such glory and such plenty that he uses no scepter save one of emerald.

From Two Cities—A Chronicle of Universal History to the Year 1146 A.D. by Otto of Freising

Preste Iuan de las Indias" (Prester John of the Indies) positioned in East Africa on a 16th-century Spanish Portolan chart/Wikimedia commons

Did Bishop Hugh, like an itinerant minstrel,i

Prester John's Letter

In 1165, several European monarchs received letters from Prester John in which the king–priest boasted of his wealth. The most famous was a message to the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos. The letter made a deep impression on medieval audiences, circulating in many versions and reaching Slavic monasteries as early as the thirteenth century.

There is a phoenix bird in my kingdom; on the new moon it makes a nest, brings fire from the sky, burns its nest, and burns itself there too. And in those ashes, a worm is born, then it is covered with feathers and becomes the same bird, this bird has no other progeny. And it lives for 500 years. In the middle of my kingdom, the River Eden flows out of Paradise. In the same river are mined precious stones: hyacinth, sapphire, pamphire, emerald, sardonyx, and jasper, hard and shining like coal.

From Legends of the Indian Kingdom, in the Ephrosin Belozersky manuscripts (fifteenth century)

Manuscript miniature of Maria of Antioch with Manuel I Komnenos/Wikimedia commons

Historians now believe that the letter was written in a Jewish community in Europe and was intended to denounce the existing European ways by comparing them to an ideal and pious kingdom. However, no one apparently understood the irony of the denunciation. As a result, the satirical text was taken as unconditional proof of the existence of Prester John, and the letter was a hit! From then on, King John was sought by everyone: kings, popes, merchants, and ordinary travelers.

There is no thief or robber or envious person in my land, for my land is full of every kind of wealth. And there is no beast, toad, or snake in my land, and even if they appear, they die at once. I have a land where peppers are grown; everyone goes to get them.

From Legends of the Indian Kingdom, in the Ephrosin Belozersky manuscripts (fifteenth century)

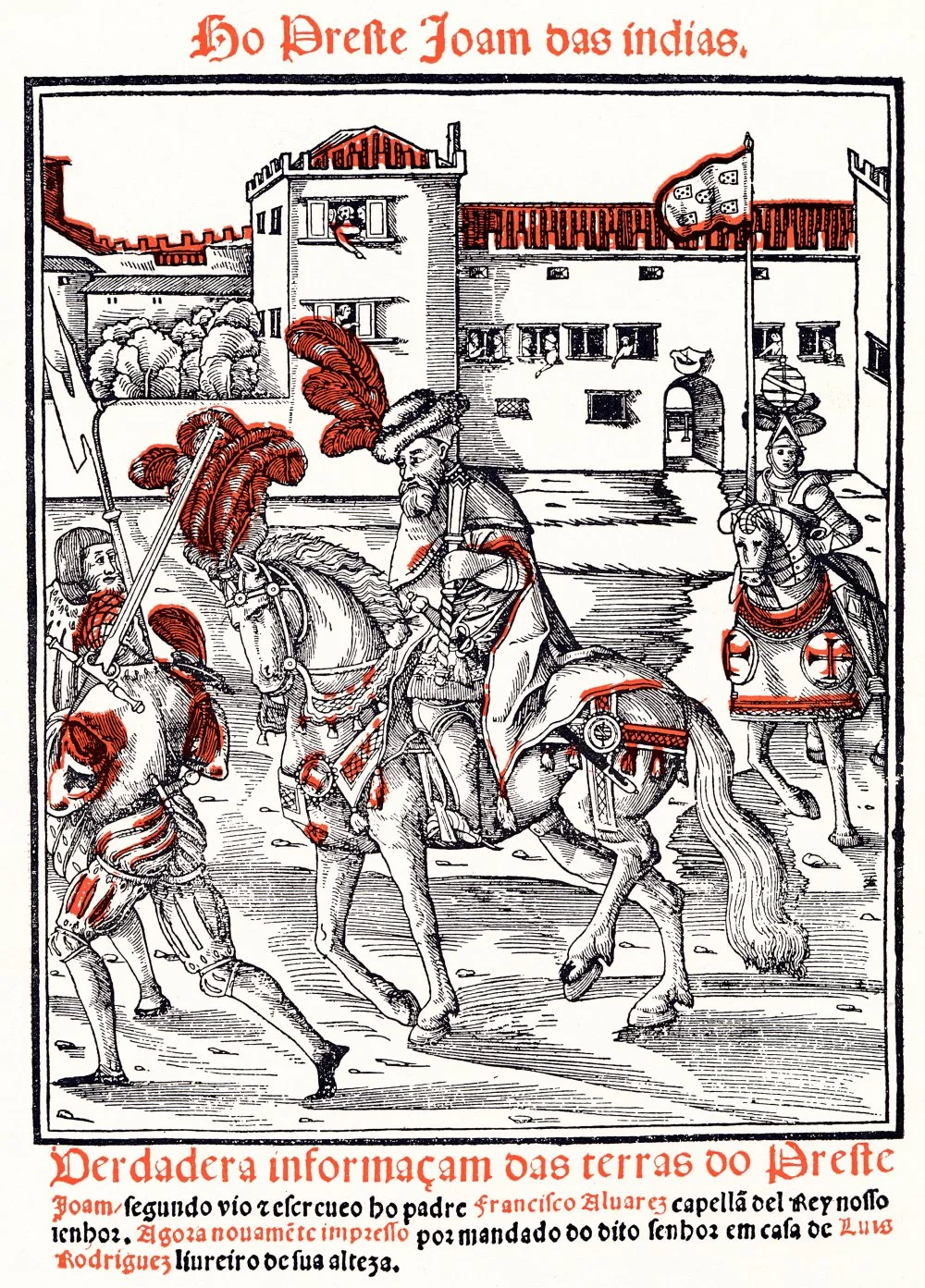

Prester John in a 16th century Portuguese engraving/Alamy

In Search of the Mysterious Kingdom

In 1177, Pope Alexander III sent a delegation with a letter containing a reply to Prester John. The delegation was led by the pope's personal assistant, Philip. However, they never returned, presumably having perished somewhere in the Arabian Desert.

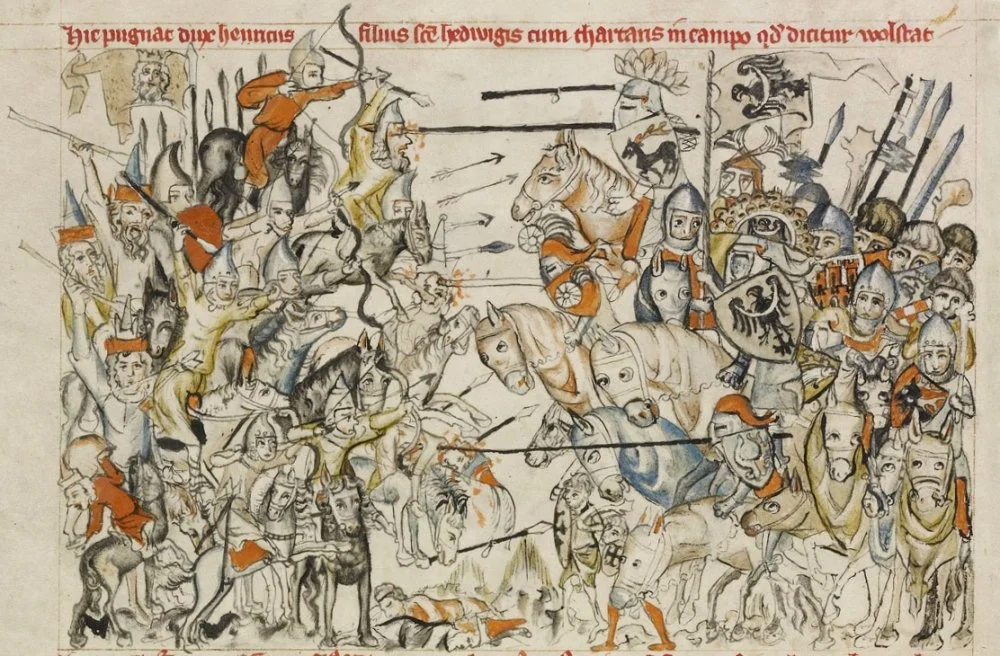

All subsequent travelers to the East searched, in one way or another, to find any sign of the existence of Prester John's kingdom. For example, the Franciscan monk Giovanni da Pian del Carpini, who traveled to the Mongol Empire in 1245, wrote that the son of Chinggis Khan went on a campaign against the Christians of Prester John ‘in the greater India’, but that they defeated the Mongols by military cunning. It is said that Prester John put warrior figures, cast in copper and hollow on the inside, on horses. They poured into them a combustible mixture that Carpini calls ‘Greek fire’.2

Pope Alexander III on a fresco in the Palazzo Publico (Siena, Italy). 14th century/Wikimedia commons

William of Rubruck, who went to the Mongol Empire soon after (1253–55), is much more skeptical of the legend. He mentions a certain ‘Nestorian shepherd, a powerful man’ who supposedly ruled over the Nestorian Naiman people, declaring himself king and seizing power in the Qara Khitai khanate, a Khitan state in Central Asia. ‘The Nestorians called him King John and said ten times as much about him as was true,’ Rubruk humorously remarks. He speaks of how he traveled through the pastures of this John, and ‘no one knew anything about him except a few Nestorians’. According to Rubruck, John's brother, a ‘mighty shepherd’ named Unk (Ong Khan), was the ruler of the Merkit tribe and owned the future capital of the Mongol Empire, Karakorum. King John died without heirs, and all power passed to Unk. But soon Chinggis Khan would conquer the former possessions of ‘King’ John and his brother.i

Mongolian cavalry on a European medieval miniature (left). The Battle of Legnica (1241)/Wikimedia commons

Rubruck's information about the location of John's kingdom also parallels the fictional ‘Letter of Prester John’ of 1165:

Among other things, we have a sandy sea. It is never in one place: from wherever the wind blows, a wave comes; and they find these waves on the shore 300 leagues away. No man can cross that sea, by ship or otherwise. And whether there are people beyond this sea or not, no one knows. From this sea flow many rivers into our land, in which there are tasty fish. Away from that sea, three days' journey away, there are high mountains from which a river of stones flows: large and small stones fall by themselves for three days. But those stones go into our land, into that sandy sea, and the waves of that sea cover them. Near that river, a day's journey away, there are high deserted mountains, the tops of which cannot be seen by man.

From Legends of the Indian Kingdom, in the Ephrosin Belozersky manuscripts (fifteenth century)

So, we are left with the description of a sandy ‘sea’ and high mountains with rocks rolling down from them. What does that remind you of? It could be a description of Central Asia in the area of modern Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan perhaps? Rubruck mentioned the Qara Khitai kingdom, where Nestorian Christians were said to be among the rulers. In the twelfth century, this state occupied the territory from the Amu Darya and Balkhash to the Kunlun Shan and Bei Shan highlands. The capital was the city of Balasagun in the Chüy River valley.

However, Marco Polo, who returned from China half a century later than Rubruck, places the land of Prester John somewhere in northern China, adding a romantic touch to the story. Allegedly, in 1200, Chinggis Khan sent word to Prester John to ask for his daughter's hand in marriage. John replied: ‘Whence arises this presumption in Chinggis Khan, who, knowing himself to be my servant, dares to ask for the hand of my child? Let him know from me, that upon the repetition of such a demand, I shall put him to an ignominious death.’ Enraged at this reply, Chinggis Khan put together a very large army, at the head of which he entered Prester John’s territory and killed him. After this, Chinggis Khan took control of more kingdoms and cities.i

Kublai Khan meeting the brothers Polo and Marco at Shangdu en 1274/Wikimedia commons

Christians in the East

The legend of Prester John probably kept alive the memory of Christian rulers in the East. Nestorian Christians were found among many Mongolian and Turkic tribes. Eastern Christians most likely inherited the Christian faith from people converted by the apostles Thomas and John, who preached in India and China in the mid-first century. But Nestorian merchants from Palestine and Syria also played an important role, actively traveling through the East and spreading their faith. The religious tolerance of the Mongols and their sympathy for Christianity are well known. For example, Chinggis Khan's great-grandson Sartaq, who briefly ruled the Golden Horde (1255–1256), was a Nestorian Christian.

Hulagu with his christian wife Dokuz Kathun/Wikimedia commons

The Final Attempts to Find Prester John

As the centuries passed, and the more Europeans learned about India and China, the clearer it became that the magical kingdom of Prester John would not be found there. Columbus had discovered the route to India—which was why the Native Americans were called Indians—but the descendants of the Christian king were not to be found in the Americas either. And so, the search turned to Africa. For a short time, Christian Ethiopia was considered the kingdom of Prester John.

A map of Prester John's kingdom as Ethiopia. Ortelius' Atlas/Wik

The last serious mention of the king–priest was in the early eighteenth century. After that, there were no more unexplored places on the planet, and Prester John was relegated to humanity's attic with the rest of its abandoned toys and rejected theories. However, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the legend of White Waters (Belovodye)—a Christian paradise in the East—became popular among Russian schismatics,i

The valley of the Bukhtarma River, the land along the banks of which was originally called Belovodye/Wikimedia commons