In Kazakh tradition, when a son gets married, the phrase kelіn tüsiru is commonly used, which translates to ‘bringing down the daughter-in-law’. The verb tüsiru has various meanings, including to drop, to unload, to catch, and to acquire. One way to interpret this expression would be ‘to help the daughter-in-law dismount from a horse’. Similarly, the term qonaq tüsiru, meaning ‘to receive guests’, is used for the ritual of assisting esteemed guests in dismounting from their horses, carts, or camels. However, the use of kelіn tüsiru evokes the image of a daughter-in-law descending from somewhere above. Let us delve into a few examples of oral literature to explore this perspective further.

The Swan Maiden, the Daughter of the King of the Peris

Kazakh folklore and genealogical legends have a captivating tale of a voyager who crosses paths with swan maidens as they bathe. These graceful beings are known as su perіsi, or water peri. The word peri, originally of Islamic origin, represents the ancient, and almost universal, lore of water sprites, which often take the form of a swan. According to legend, these women are the daughters of the king of the water peris.

According to the legend, the lead character captures one of these swan maidens by taking her shoes or feathered attire and forces her into marriage. However, the maiden only relents if he abides by specific conditions. She insists that the man never look at her while she combs her hair, and that he avoids the sight of her legs and armpits. Perhaps this is because she combs her hair with her head off or she has a delicate crown, revealing her brain. Or perhaps her legs are bird-like, while her lungs may be visible beneath her armpits. In essence, the girl retains the vestiges of her inhuman, supernatural origins.

Sadly, the hero violates one of these conditions, resulting in the maiden transforming back into a swan and flying away, leaving him and their son behind. In some versions, the son becomes a respected ruler and the founder of a tribe, while in others, he tragically succumbs to the evil eye during his childhood.

Kazakh folklore has many other similar genealogical plots involving swan maidens. One tells the story of a wounded warrior named Kalsha Kadir, who was saved by a swan. The warrior and the maiden marry, and their son, named Kazak, becomes the ancestor of the Kazakh people. In the epic cycle Forty Batyrs of Crimea, two swan maidens, both daughters of the king of the peris, come to the aid, in swan form, of an orphan boy named Anshybay—a future batyr (a hero or warrior) and the savior of his people—and eventually even become his wives. Similarly, the saga of the Nibelungs contains an episode where the Burgundians stop on the banks of the Danube, near the Huns’ territory. Here, a hero named Hagen encounters some swan maidens who tell his fortune. To commemorate this encounter, the place is named Schwanfeld.

In the 1970s, folklorist Edige Tursunov suggested that the trope of the swan maidens likely originated from Turkic mythology as it has many similar episodes to those in Kazakh folklore. Building on this idea, S. Kondybay reconstructs the ancient concept of the swan ancestor of all Turkic peoples and the populations tracing their lineage matrilineally from these swan origins. He systematized various Kazakh ethnonyms and toponyms associated with swans and proposed the hypothesis that stories of swans in ancient Greek and Indo-Iranian mythology may be fragments of a proto-Turkic mythology.

It is worth mentioning that within the traditional sal-sere military brotherhood, one of its members would dress in a swan costume. As the sal-sere cavalcade entered a village, this individual would ride around the village emitting calls resembling those of a swan. Similarly, in ancient times, Kazakh warriors would let out swan-like calls as they charged their enemies in battle; this war cry is known as qiqu in Kazakh. Interestingly, this nomadic custom has also been documented in Slavic folklore but with a negative connotation, displaying a somewhat unfavorable attitude towards these ‘geese and swans’, the totems of Turkic nomads.

The Celestial She-Wolf

The ancient Turks have many genealogical legends centered on the figure of a celestial she-wolf, also considered an ancestral figure. One legend tells the story of a she-wolf nursing an orphan who grew up to be the ancestor of the Wusun Gunmo tribe. Another tale recounts how a she-wolf bonded with a boy who was left without limbs by enemies who destroyed his tribe. The young man was eventually killed by his enemies, and the she-wolf sought refuge in the Ötüken Mountains, where she gave birth to his ten sons. These offspring, known as the heavenly Turks, made their homes throughout the Altai region. The she-wolf also guided the two families of the Kiyat tribe, who sought shelter in the Ergenekon mountain valley after their tribe was decimated.

Wolf totemism is an important part of the oral traditions of Kazakh culture. In the epic Alpamys, the main character’s father is named Baibori, which means an ancient and respected leader of the wolf pack. The saga also frequently emphasizes the börı zat, or the wolf-like essence and origins of the hero and his son, and their inherent börılık qylu, or their wolf-like actions and behavior. Alpamys’s wife’s name, Barshyn, could refer to either an eleven-year-old eagle or a she-wolf (berі versus barshyn). Notably, there was a medieval city named Barshynkent in Kazakhstan.

Kazakh myths surrounding the wolf also contain some taboo names such as qūrt. Interestingly, Qūrtqa is also the name of the protagonist’s wife in the epic Qoblandy. Zh. Karakuzova, a cultural expert, interprets this epic, particularly its beginning, as cosmogonic in nature. The brave Qoblandy batyr goes in search of a bride in a distant land, triumphs over rivals in competitions, and marries Qūrtqa. Her father is a khan known as Köktım Aimaq (heavenly world), and when he becomes the batyr’s father-in-law, he gives him a dowry of four clouds, each situated in every cardinal direction, as a sign of divine blessings. Some versions of the epic mention Qūrtqa’s mother instead: Köklen, the sorceress, the heavenly old woman and the queen of the elements.

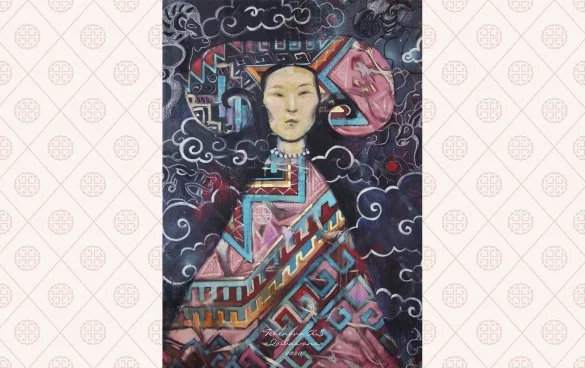

Alua Tebenova. Qoibas-ana. 2020

The Daughter of the Snake King

Another prevalent trope in Kazakh fairy tales involves the hero marrying a snake maiden. This motif is similar to the popular Melusina story found in various other cultures, where the hero discovers that his beautiful wife is actually a snake or dragon. However, the hero also sometimes knows his bride's true identity from the start. For example, he befriends a snake-man, ventures with him into a snake hole, and marries this man's sister. In the tale ‘Er Töstık’, Bapy Khan, the king of snakes, gives his daughter to the hero in marriage. However, she tragically dies during the difficult journey from the underworld to the human realm.

Another tale tells of a khan falling in love with a woman called Altynşaş-Goldilocks before ever laying eyes on her. He begins to have feelings for her when he sees a strand of her sparkling golden hair floating in a river. S. Kondybay suggests that her hair may represent a snake, linking Altynşaş to the gorgon Medusa. This motif in Kazakh folklore is also clearly connected to one from a medieval Kimak legend about the goddess of the Irtysh River as recorded by the Persian author Gardizi. ‘Once, Shad stood on the banks of the Irtysh with his people; a voice was heard: “Shad, have you seen me in the water?” Shad saw nothing except a hair floating on the surface of the water; he tethered his horse, entered the water, and caught the hair, only to discover that it belonged to his future wife, Khatun. He asked her, “How did you fall?” She replied, “A crocodile grabbed me from the riverbank” (the Kimaks hold reverence for this river, worshiping it as a god).’ Of course, the crocodile in the Irtysh River was introduced thanks to the Persian author, and the original story likely referred to a water snake, dragon, or a similar creature. The historian S. Akhinzhanov has also commented on this fragment, explaining that the associative connection between the concepts of a woman’s hair floating in a divine river, the woman Khatun, and the dragon-snake with a deity of the lower world became the genealogical basis for the origins of the Kimak-Kai.

The cult of a snake or dragon among Turkic peoples was extensively researched by S. Kondybay. He dedicated half of the third book of his fundamental study, Mythology of Pre-Kazakhs, to this subject. He proved that the totemic reverence for snakes, viewed as ancestors, is a defining characteristic of proto-Turkic mythology. The Turks, including the Kazakhs, preserved the totem cult of the mother snake, with stories evolving into a complex of mythological ideas about the snake. However, over time, in patriarchal societies, the function of the snake as a primordial mother was forgotten. The snake and the dragon gradually acquired characteristics associated with worshiping male ancestors. However, the original belief persisted in a condensed form and can be easily reconstructed.

Ürker Maidens—The Pleiades

In Kazakh folktales and legends, a prevalent theme involves a hunter on a deserted steppe encountering an unknown village inhabited solely by maiden fairies known as peris. One of them shares his bed and promises to become his wife on the condition that he doesn't fall asleep before dawn. The hunter fails to meet this condition and wakes up alone in the wilderness. Later, he receives news that he must come to a specific location in nine months. There, in a cradle hanging from the sky, he finds his son, born of the peri maiden.

S. Kondybay links this story to the Pleiades constellation, known as ürkers in the Kazakh language. According to the Kazakhs, ürkers are maidens who descend to earth in the spring, at the beginning of the new year. They were the principal characters in the astral mythology of nomads, from the Scythians to the Kazakhs. Sometimes, the ‘ürker–Pleiades’ are represented as a group of seven or fifteen maidens. Other personifications of this constellation include six brothers and a sister, or a khan whose daughter named Ülpıldek was abducted by the Seven Thieves (Ursa Major). In some versions, ürkers take on the form of thieves who steal two of the khan's horses (Ursa Minor) tied to the Iron Stake (Polaris). The ürkers are often chased by watchmen (Ursa Major), and so on. Nevertheless, the primary personification involves a group of maidens, one of whom develops a relationship with an earthly man.

Thus, the bride in Kazakh mythology involving ancestral figures often possesses a non-human nature. She could be a swan, a snake, a celestial she-wolf, or even a star. This could be the origin of the expression kelіn tüsiru. These mythological brides typically do not really become brides, and even if they do, they often clash with their husband's relatives, most commonly with their father-in-law, like Qūrtqa in Qoblandy and Kenjekei in ‘Er Töstık’. Those who bear children are strangely not called ana (mother), and their motherhood is irrelevant to the story. Perhaps it was challenging to integrate such supernatural characters into society. On the other hand, in the Kazakh mythological tradition, several characters are referred to as mothers, though nothing is known about their children. However, this will be discussed in the next lecture.