The Flesh of My Raft

The Most Scandalous 19th Century Painting: Cannibalism and Politics

The Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault. 1819/Louvre Museum/Wikimedia Commons/Louvre Museum/Wikimedia Commons

This painting is part of the collection of the Louvre Museum in Paris.

In 1819, the Paris Salon, the largest exhibition of regular painting, turned into a colorful hymn to the newly restored monarchy.i

Charles X Distributing Awards to Artists Exhibiting at the Salon of 1824 at the Louvre January 15th 1825, 1827, Musée du Louvre, Paris/Wikimedia commons

Thus, it was all the more surprising that amidst this monarchic parade, they somehow allowed Théodore Géricault's The Raft of the Medusa to be a part of the exhibition. Obviously, it would have caused further comment not to include it as rumors about this grandiose and unconventional art project had been circulating for over a year.

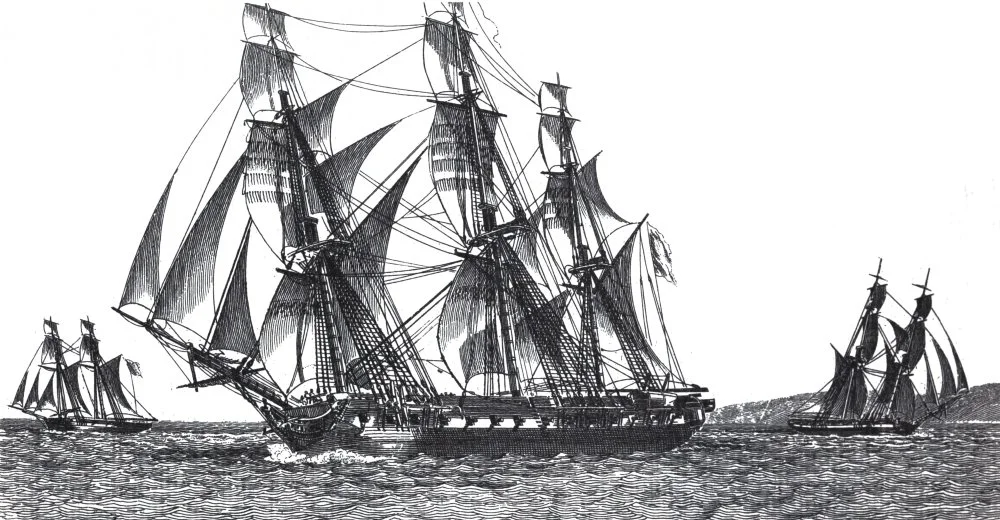

This monumental canvas (5 by 7 meters) depicted the tragedy of the Medusa, a French frigate, which after the end of the Napoleonic wars, was converted into a transport and passenger ship. It was commanded by the royalist Captain Hugues Duroy de Chaumareys. In July 1816, as part of a small fleet, the Medusa was carrying passengers, primarily French officials and military personnel, to Senegal, the new French colony. Additionally, the newly appointed governor of Senegal, Julien-Désiré Schmaltz, who was a loyal supporter of the crown, was also on board.

The frigate Medusa in 1816. Engraving/Wikimedia commons

On 2 July, the Medusa, the flagship of the fleet, ran aground 50 kilometers from the Senegalese coast due to a mistake in the calculations of its navigators. All attempts to move it were unsuccessful. The other ships of the fleet didn't dare approach the shallows and moved toward the shore instead. A rather chaotic and inefficient evacuation of people began. As there weren't enough lifeboats for all the passengers, the decision was made to build a huge raft.

Meanwhile, the hull of the Medusa cracked, threatening to sink the ship. The captain, the governor, and part of the crew transferred to the boats, while the remaining passengers and soldiers were placed on the raft. The boats were expected to tow the raft, but the wind picked up, causing rough seas. Realizing they couldn't handle towing, the crew cut the ropes and headed for the shore, where they safely landed.

This overloaded and uncontrollable raft, which had practically no provisions and only very modest supply of water, housed 147 people of the the Medusa’s 240 passengers (another 17 people decided not to board the raft and presumably risked staying on the sinking ship, while the rest were accommodated in the boats). The waves washed people off the raft, fights broke out for a safe place in the center, and, thus, on the first night, about twenty people were killed. In the following days, the storm intensified and dozens of people fell into the cold seas. On the fourth day, only sixty-seven people remained on the raft, most of them already dehydrated, weakened, and injured. Among the survivors were some who had chosen to survive by eating the flesh of the deceased. The others looked on in horror at the cannibals but couldn't stop them. On the eighth day, fifteen of the strongest and healthiest people threw all the weak and wounded overboard in order to preserve drinking water they collected during the rain.

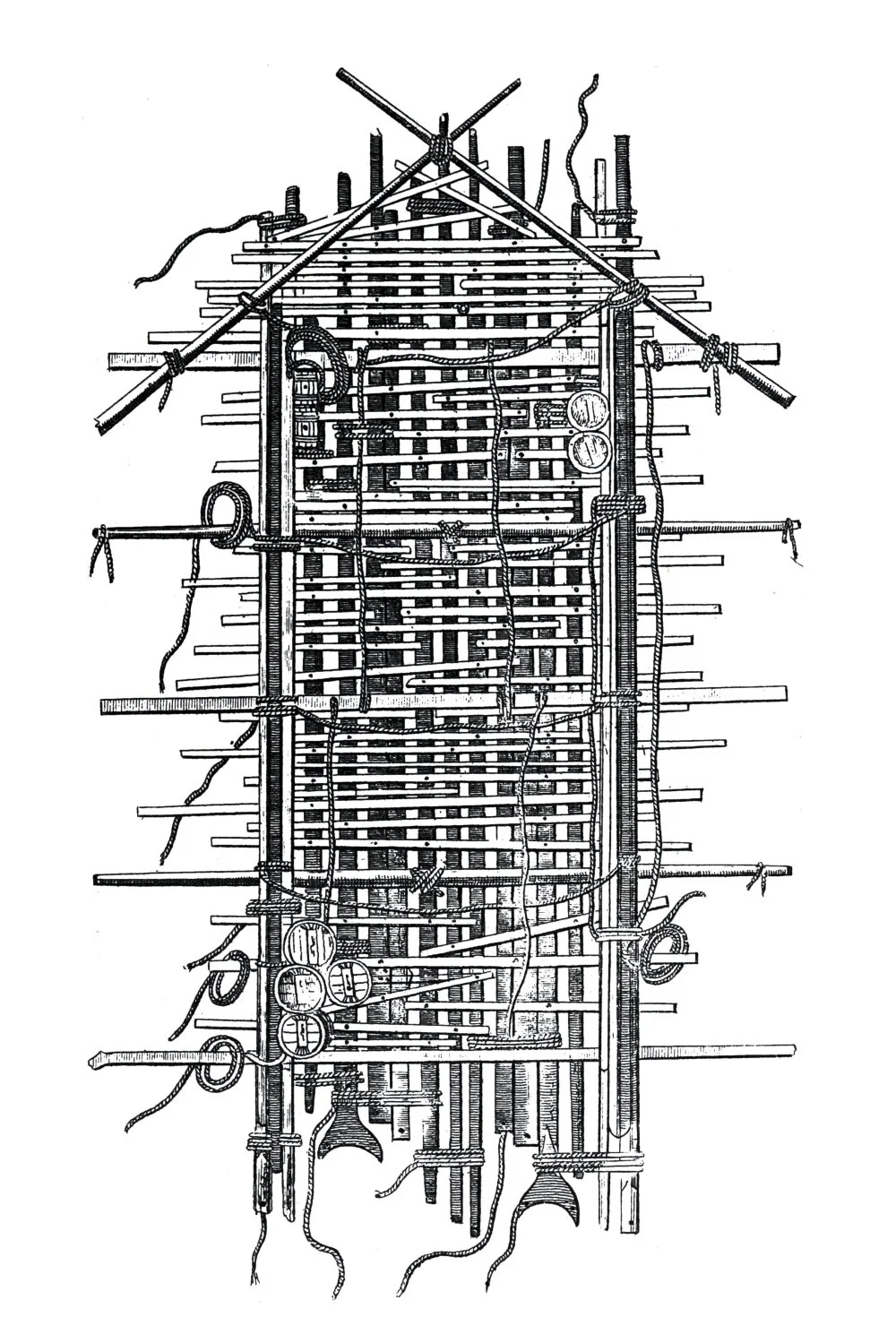

Plan of the Medusa raft/Wikimedia commons

Meanwhile, from the shore, there were hardly any attempts made to rescue the raft. Only on the thirteenth day did a brig called the Argus, one of the ships in the fleet, set sail toward the Medusa, which had remained stranded and listing but miraculously not sunk. However, it didn't sail there in the hope of saving any of the survivors. The crew of the Argus had, sadly, quite a different task: they had been ordered to lower a chaloupe into the water, reach the Medusa, and retrieve the barrels of gold and silver—the colony's treasury.

Along with the gold, the team from the Argus found three survivors (of the seventeen) on the Medusa. Another fourteen had presumably built a raft over those two long weeks, attempted to reach land on it, and apparently drowned. On their return journey, the Argus accidentally came across the drifting first raft, upon which crawled semi-mad people, resembling more skeletons than humans. Fifteen people were taken off it, five of whom died after being generously fed as the ship doctor was unaware that starving people shouldn't be given a lot of food at once.

The horrifying details of what had happened soon reached France. An investigation was launched, which was followed by a court trial. And it was that very trial that outraged the French. Instead of facing the death penalty, as mandated by all maritime and earthly laws for abandoning his ship and his passengers, Captain de Chaumareys was sentenced only to three years in prison. The governor, who took no action to rescue the colonists, got away with simply resigning his position. The story of the Medusa came to be seen as evidence of the wickedness and dishonor of the royalists, becoming a powerful weapon in the hands of the republicans. And so, the inclusion of The Raft of the Medusa at the loyalist exhibition was a bold statement directly against the crown—a significant scandal.

Detail of the crew member waving his handkerchief to draw the ship's attention/Wikimedia commons

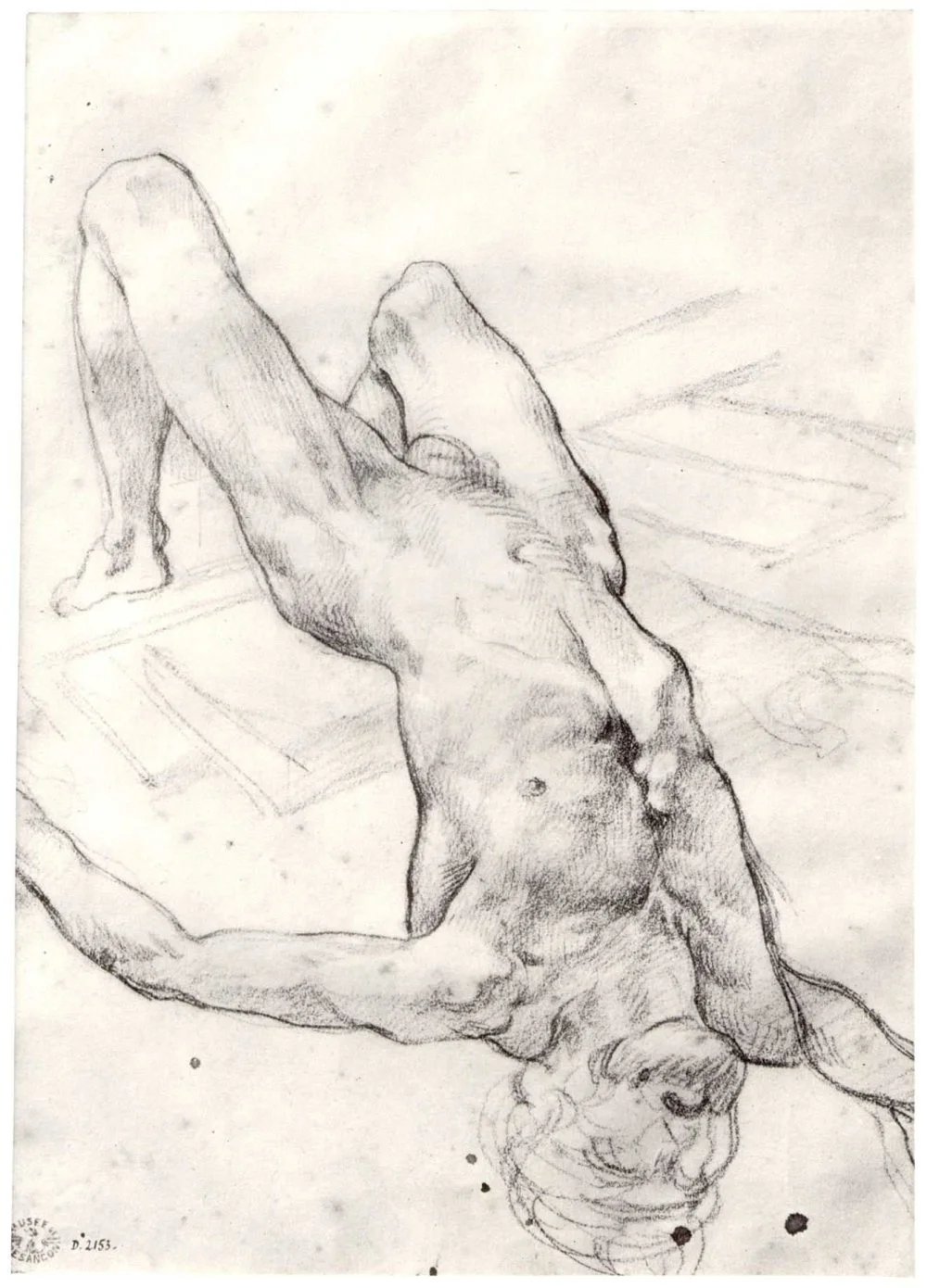

Géricault undertook this work with all seriousness. He met with survivors of the incident and meticulously interviewed them. He went to the morgue and drew bodies of various degrees of freshness to master the color and anatomy of the dead. He asked a survivor from the Medusa, who happened to be a carpenter, to build him a small model of the raft. Then, he made wax models himself and placed them on that raft, changing the lighting. This was the composition he used to paint The Raft of the Medusa.

Géricault: figural study for the «Raft of the Medusa»/Wikimedia commons

After the exhibition, critics loyal to the crown accused Géricault of offending public morality, calling the painting disgusting, shocking, and depraved. It was somewhat difficult to criticize the artist for the abundance of dead bodies on his canvas (especially if one recalls how many paintings depicting themes such as the crucifixion, deposition from the cross, and entombment were at the exhibition), but some of those bodies were clearly partially eaten!

Not a single local gallery wanted to display or even associate with The Raft of the Medusa, but the painting was enthusiastically received in England, where it was transported for permanent display. The English willingly paid to see the masterpiece, eagerly discussing the monstrous French practices in maritime affairs and legal proceedings and generally condemning Gallic customs and characters. After the artist's death in 1824, the painting returned to France, where it eventually found its place in the Louvre.

A passage from L'Assommoir by Émile Zola vividly describes the experience of seeing the painting:

‘Then, without stopping, they passed through an endless series of small rooms. The glare of golden frames dazzled their eyes. They glanced at the flickering canvases: there were too many paintings to examine them all. To truly understand them, one would have to stand before each for no less than an hour. Good Lord, how many paintings! Hundreds of them! And how much money was spent on this! Suddenly, Madinier stopped before The Raft of the Medusa and explained the plot. Everyone was shaken and stood silently, not moving. When the company moved on, Bosch summed up the general impression with one word: “Great!”’

The Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault. 1819/Louvre Museum/Wikimedia Commons/Louvre Museum/Wikimedia Commons