Grass, mercury and worms

The long and expensive history of the colour red

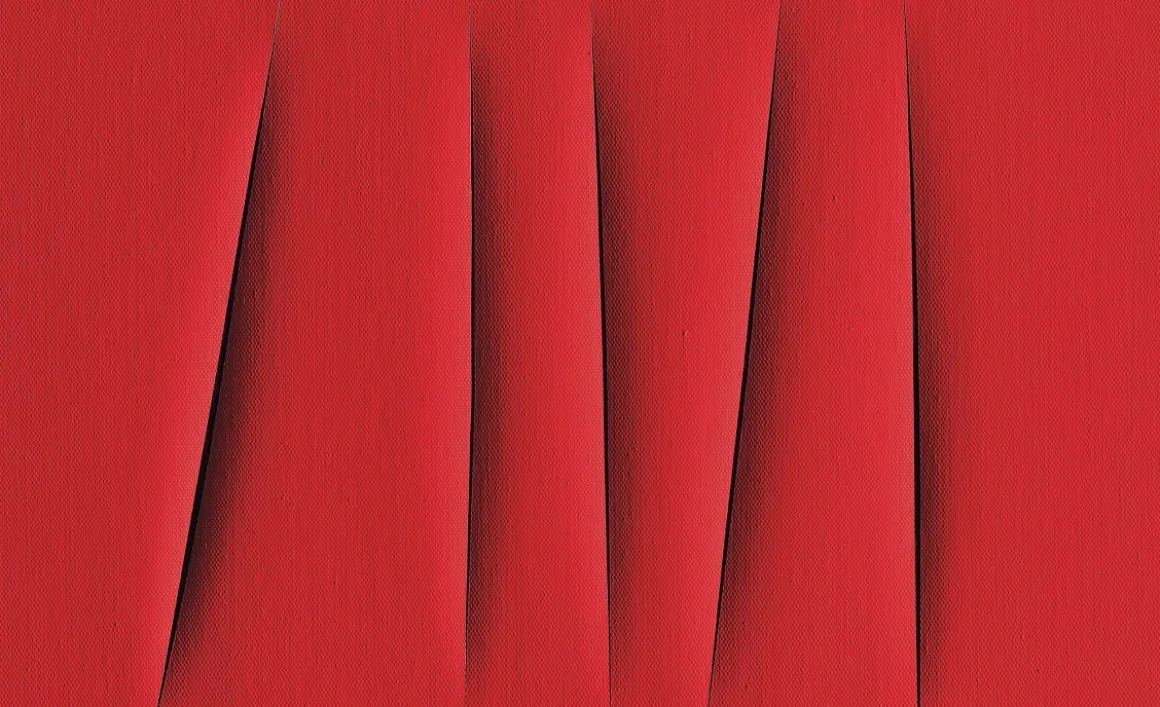

Lucho Fontana. Spatial concept. Expectation. Fragment. 1967. Canvas, pigment. Private collection/christies.com

Bright colors attract the attention of animals searching for food, including us humans. They evoke an emotional response in us that we usually interpret as pleasure. To put it simply, people like colors.

If predators or herbivores, and not humans, had evolved to become the intelligent dominant species, the coloring industry would have been in a dire state. However, in species like humans, whose survival is directly dependent on the skill to quickly notice red berries, yellow fruit, and green caterpillars, the love for bright and diverse colors is deeply ingrained within our evolutionary programming.

Since ancient times, the desire to color the world around us, our bodies, our homes, and our clothes has been a very important human impulse. Scientists believe that using dyes is one of the attributes of the ‘modern way of life’ and that early humans did not grasp immediately or fully. However, they didn’t have many options to begin with as fast dyes are very rare in nature.

Bison Magdalenian polychrome/National Museum and Research Center of Altamira/Wikimedia Commons

As for red, the brightest color of all, dyes of shades of red continued to be amongst the most expensive items in ancient markets for a long time.

First, There Were Stones

The main red dye of the Stone (Paleolithic) Age was ochre, which is clay mixed with ferric hydroxide. It was applied to the dead during burials, used to treat animal skins, and possibly also used for drawing on the skin. Some modern-day tribes that live according to the traditions of the Stone Age still use ochre to paint their bodies. Several years ago, a group of archeologists led by Wil Roebroeks from Leiden University (the Netherlands) discovered evidence of ochre being used by European Neanderthals in the territory of modern Holland. The findings date back 150,000 years, which makes them the most ancient proof of the use of dyes by the Neanderthals. Homo sapiens, who initially only lived in Africa, started using dyes even earlier, around 200,000 to 300,000 years ago.

Hematatis/Alamy

40,000 years ago, paleolithic artists also painted on cave walls using iron clay powder, and this is still being used in tempera art as a mineral pigment and provides a red-brown color.

Manohar. Emperor Jahangir Weighs Prince Khurram. Page from Tuzuk-i Jahangiri. 1610-1615/British Museum, London/Wikimedia commons

Of course, ochre and iron clay can simply be called ‘red’, but their shade is closer to brown. However, red lead oxide gives a bright orange red that was used to not only dye clothes but also to make paint and makeup by the ancient civilizations of Egypt, India, China, and Mesopotamia. The toxicity of this dye was unknown for a long time, and thus white lead was still being burnt to get saturnine red in order to make ‘blush’ in the eighteenth century.

Another more dangerous dye, crimson mercury sulfide, aka cinnabar, was very popular in China. Unaware of its poisonous properties, the Chinese sincerely believed that a color that was so pleasant to look at could only be good for one’s health and not harmful, generously adding it to all medicines. Even the mythical elixir of eternal life that Chinese alchemists had been looking for for centuries was known as ‘the red cinnabar pill’.

Сhinese carved cinnabar lacquerware, late Qing dynasty, China. Adilnor Collection, Sweden: Danieliness/Creative Commons

Fortunately, mercury sulfide was rare and difficult to source, and there were only a few places in the ancient world where it could be found. It was, therefore, very valuable, used sparingly and, in general, mercury poisoning occurred less often and more slowly than lead poisoning. In addition, neither saturnine red nor cinnabar were suitable for dyeing fabrics. These dyes were not very suitable for use on soft materials that were in frequent contact with water.

Pig Glands and Other Things

In China, red was ritualistically important and symbolized fiery male ‘yang’ energy. Therefore, it is not surprising that many red dyes originate from there.

During the Yǎngsháo period (5000–3000 BCE), craftsmen were already creating ceramic pieces painted in red and black. Under the rule of the Han dynasty (206–220 BCE), Chinese craftsmen weaving and dyeing scarlet silk fabric were famous across the world. During the time of Tang and Song, a new trend emerged: the gates of houses and temples were starting to be painted red. Wealthy and high-ranking individuals would often paint their entire house red. It is for a reason that one of the most well-known pieces of Chinese classic literature is called Dream of the Red Chamber (written by Cáo Xuěqín (1715–63)). The dyes used for these purposes were usually those derived from various plants, including safflower, sorghum shoots and stems, and poinciana wood from India.

The thirteen emperors Attributed to: Yan Liben (Chinese, about 600–673) second half of the 7th century C.E./MFA Boston

In ancient China, makeup was overlooked at all. It was applied to the face and lips not to attract potential partners but to honor and placate the gods during rituals. Eventually, a thick layer of makeup on the face became an absolutely mandatory element of the appearance of any high-ranking lady of any age. In polite society, any lady being seen without makeup on her face was considered immoral flirting. This was how Du Fu described one such presumptuous girl in his poetry:i

‘By own beauty so was she amazed

That dared having no blush or powder on her face

Come to the palace she.’

The first evidence of lipstick and blush appeared in China during the Shang dynasty (eleventh to sixteenth centuries BCE). These items were prepared by mixing the juice of safflower petals with ground ox adrenal glands and pig’s pancreas to obtain the required consistency and adhesive ability.

Painting Of A Woman From Turpan Oasis C.7th-8th Century, Astana Tombs, Xinjiang/Legion-Media

Madder

Eastern dyes were already being brought to the west by the Phoenicians, but they were rare and expensive. The West had its own source of red dye, the European madder, growing in the Mediterranean, Asia Minor, and Central Asia, as well as Western Europe. Here, fabrics were dyed using madder roots, which provided a full gamut of cherry red colors from pale pink to intense cherry. Madder also grows in Kazakhstan, and it has been traditionally used here as well to dye fabrics. For example, Mound 1 in the Laskowski burial grounds that date back to the Bronze Age contains some samples of woolen hand-woven ribbons dyed with madder.

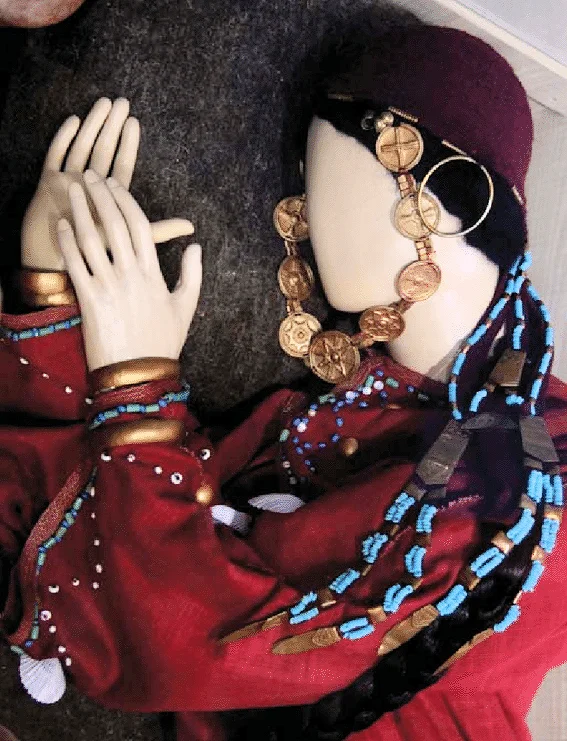

Andronovo costume set. Headwear, braid adornment, dress and adornments. Reconstruction. Lisakovsk Museum of History and Culture/Emma Usmanova/Wikimedia Commons

In Egypt, this dye was being used from at least 1500 BCE, and fabric dyed using madder was found in Tutankhamun’s tomb. This pigment was also found in archeological digs in Pompeii. In addition, madder and the dye made from it has been mentioned by Herodotus, Pliny the Elder, and other ancient authors.

Fresco from the Sala di Grande Dipinto, Scene II in the Villa de Misteri (Pompeii)/Wikimedia Commons

Red beetles that conquered the world

Madder dyes were never really ever considered to be the ‘real’ or ideal red—they were too dark, too cold, and a little dull. The true and ideal red is the dark scarlet color of the freshly spilled arterial blood, the brightest red strip in the sky at dawn, the perfect red rose.

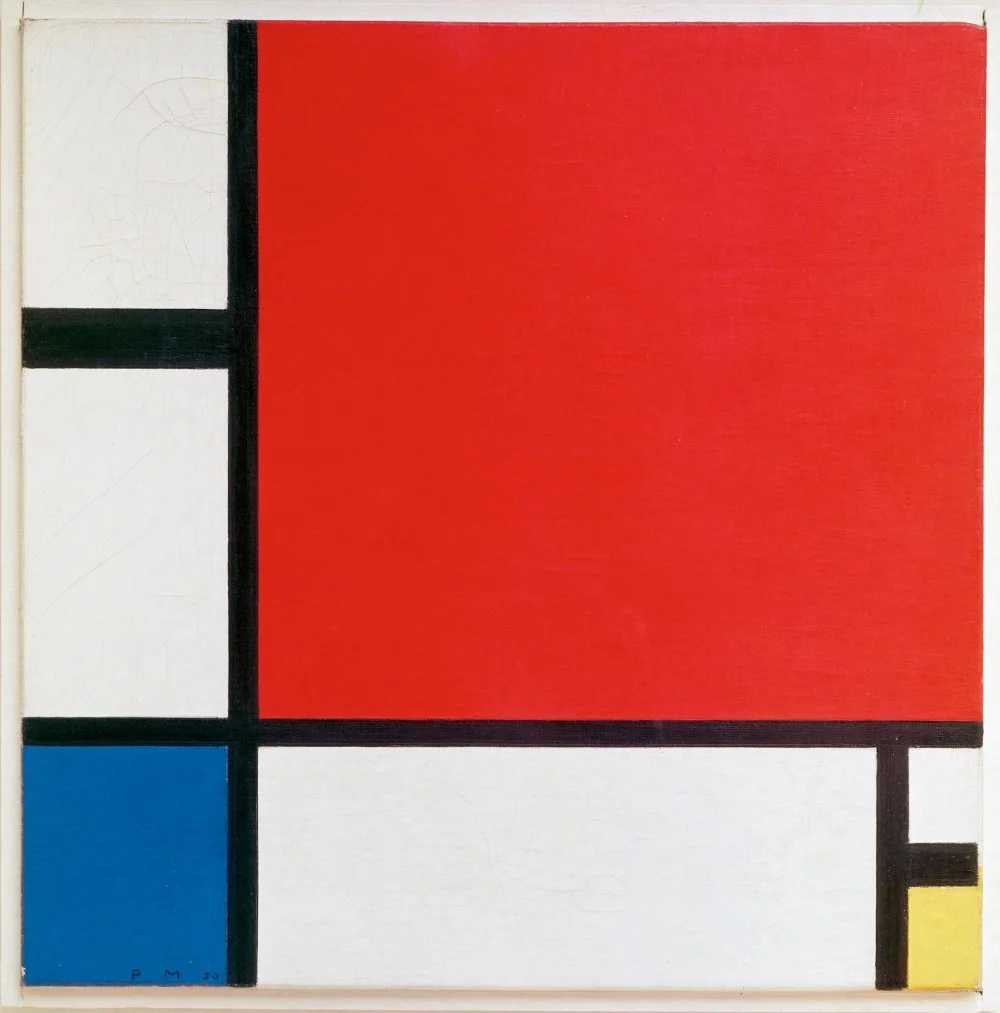

Piet Mondrian. Composition with Red, Blue, and Yellow. 1930/Wikimedia Commons

And our ancestors knew of the dye that was capable of dyeing a dress that color. It was derived from several species of insects known as cochineals.

The female cochineal insect penetrates the stems of plants (and often the roots underground) with its beak-like mouth, where it feeds on plant juices and oviposits, remaining immobile. Cochineals are removed from plants using a hard brush or a blade, dried, and then ground. The powder is then treated with ammonia or sodium carbonate solution and later filtered. The resulting dye is called carmine, stemming from kermes, the Arabic name for these hard-winged insects. Humankind has also long been familiar with the dark red dye derived from ‘worms’. Dyed red wool is mentioned in the Book of Exodus several times.

Cochineal beetle. Handcoloured lithograph from Georg Friedrich Treitschke's Gallery of Natural History, Naturhistorischer Bildersaal des Thierreiches, Liepzig, 1840/ Legion-Media

Before the discovery of the Americas, the most popular cochineal was Ararat cochineal, popular in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Iran. Istakhri, an Arab author of the tenth century, wrote: ‘This city is the capital of Armenia … They make woolen dresses and rugs, pillows, cushions, cords and other items made in Armenia. They also derive the dye called “kermes” and use it to stain fabrics. I found out that the source of this dye is a worm that weaves around itself akin to a silkworm.’

The world's oldest known pile carpet was found in the largest of the Pazyryk burial mounds, Altay mountains/ Hermitage Museum Saint Petersburg/Wikimedia Commons

The Mediterranean had its own carmine derived from oak dwelling cochineals, but the dye derived from them was not as bright as the one from their Ararat relatives. Another well-known carmine was obtained from the Polish cochineal insect, and it was popular in Western and Eastern Europe and the European parts of Russia. From the sixth century, this pigment was used in Europe, especially during wars, when other sources of red dye were not available. This insect was often called “the earth pearl” because it lived on the plant roots.

Letitia Grace McCurdy by Joshua Johnson circa 1800–1802/ Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/Wikimedia Commons

Concentrated carmine was ideal for dyeing not only fabrics but also all types of leather. As it was very expensive, red footwear in the end became a symbol of almost unforgivable luxury as evidenced by Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale ‘The Red Shoes’, which is about a girl’s soul being destroyed due to this unholy footwear.

Montezuma’s red gold

The New World had its own cochineals that lived on the prickly pear (Opuntia) cactus, and the Aztecs had long since learned to derive dye from them and have even branched out into farming them. The famous king Montezuma collected an annual tribute from the cities he conquered in the form of 2,000 decorated blankets and 40 sacks of carmine dye. It is thought that Hernán Cortés was the first person to bring the Mexican cochineal to Europe in the sixteenth century. Soon, the volume of cochineal import from the new world was second only to silver. The dye derived from the humble cactus bugs was carried across the Atlantic, filling ship holds, and was soon sold not just in Europe but also in Asia. The Mexican cochineal gave the brightest shade of red, which allowed the tailors of the Old World in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to invent many new shades of the red color spectrum, such as ‘flaming heart’ and ‘hell fire’.

New colour for the new times

In 1868, two German chemists, Carl Grebe and Carl Theodor Liebermann, the cousin of the great impressionist painter Max Liebermann, synthesized the red dye alizarin from anthracene, a substance derived from coal tar. Their method was accessible and inexpensive, allowing them to quickly start manufacturing alizarin dyes on an industrial scale.

The bourgeoisie rolled up their sleeves, took some loans, and started filling the world with red. Madder practically stopped being cultivated, and cochineal bugs could now happily sup the juices from their oaks and cacti without any fear of being dried and ground up. Now, bright red colors were accessible to all, not just the rich.

The Red Studio by Henry Matisse (1911)/Wikimedia Commons

Nevertheless, the perception of the color red as provocative and luxurious remained high in the public conscience. A red dress worn to a high society event would be perceived as pompous and provocative even today.

an van Eyck, Lucca Madonna, 1436. Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt, Germany/Wikimedia commons

What to read

Булгакова А., Власова Е. Палитра старых мастеров // Мир искусств: вестник международного института антиквариата. 2015. № 3. С. 100–111.

Менделеев Д. И., Соколов А. М., —. Косметики // Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона : в 86 т. (82 т. и 4 доп.). — СПб., 1890—1907

Reading Our Lips: The History of Lipstick Regulation in Western Seats of Power, Sarah Schaffer / Class of 2006 May 19, 2006

Лиза Элдридж. Краски. История макияжа / Ошеверова Л.. — Москва: ОДРИ, 2016

Болл, Филип (2001). Яркая Земля: изобретение цвета. Лондон: Викинг.