Mollusks on royal service

Purple: The Color of Gods and Emperors

Theodoor van Thulden. The Discovery of Purple, 17th century, Museum: MUSEO DEL PRADO, MADRID, SPAIN/Legion-Media

When it comes to colours, everyone has their own preferences. Some like warm colors, others are crazy about cold colors. And every season, the purveyors of high fashion choose a new favorite, only to forget it completely in a few months. However, there are some colors that people have always loved, right from ancient times to the present. One of these colors is purple, which lies on the color spectrum between crimson and violet and was once called ‘porphyry’.

Writing about the color purple, historian Michel Pastoureau says: ‘[F]irst, the incomparable brilliance of the dyes obtained from that somewhat mysterious colorant, murex; second, their solidity and resistance to light. Unlike the bases of other dyes, which faded, the coloring constituent of purple strengthened over time and was enhanced by the effects of light—sunlight, but also moonlight or a simple flame. Fabrics took on new shades and displayed changing, shimmering highlights they did not initially have. Hues varied from red to violet, from violet to black, sometimes passing through pink, mauve, or blue before returning to red. Purple appeared to be a living, magical material.’

The silk shroud of Charlemagne made with gold and Tyrian purple. The design shows a quadriga (four-horse chariot). 9th century CE/Musée National du Moyen ge, Paris

How a Dog Discovered Purple

Seven generations before the Trojan War, the Phoenician god Melqart—also known as Hercules of Tyre—decided to take his dog for a walk by the sea. The dog frolicked, grabbing and throwing shells left behind by the tide. At one point, Melqart noticed that the dog’s mouth had turned purple. He recounted this amazing story to the ruler of the city of Tyre, of which he was patron. The ruler, named Phoenix, seemed to have both intelligence and considerable commercial talent, and so he immediately started the production of purple in Tyre. For many generations, this gave the Phoenicians not only work but also considerable wealth, or so Julius Pollux, a Greek writer of the second century CE, tells us.

Purple Dye Murex (Bolinus Brandaris) (Gastropod) On A Beach In Israel, A Sea Snail. Murex Was At One Time Greatly Valued As The Source For Purple Dye/Legion-Media/Alamy

Not Simply a Color

The famous Tyrian purple was actually extracted from sea snails, originally known as murex. It was a fabulously expensive dye since it took the processing of tens of thousands of snails to obtain 100 grams of dye. In Rome, during the reign of Emperor Augustus,i

Fresco from the Sala di Grande Dipinto, Scenes in the Villa de Misteri (Pompeii).Wikimedia commons

In republican Rome, the purple stripe on the white togas worn by the patricians (which, for a long time, could be worn only by the nobility) was called a clavus (Latin for ‘a nail’, for reasons that are not entirely clear). Its width and hue indicated the origin, age, rank, or size of the owner’s fortune.

Divine Color

The Torah, the sacred book of the Jews, says: ‘Of every man that giveth it willingly with his heart, ye shall take my offering … And let them make me a sanctuary; that I may dwell among them.’ And in the long list of offerings required to make the Ark of the Covenant, where God will dwell, purple is mentioned. The ark itself is to be made entirely of gold and precious wood, but the tabernacle (a tent-like structure that covers it) is to be made of cloth that is dyed purple among other colors.

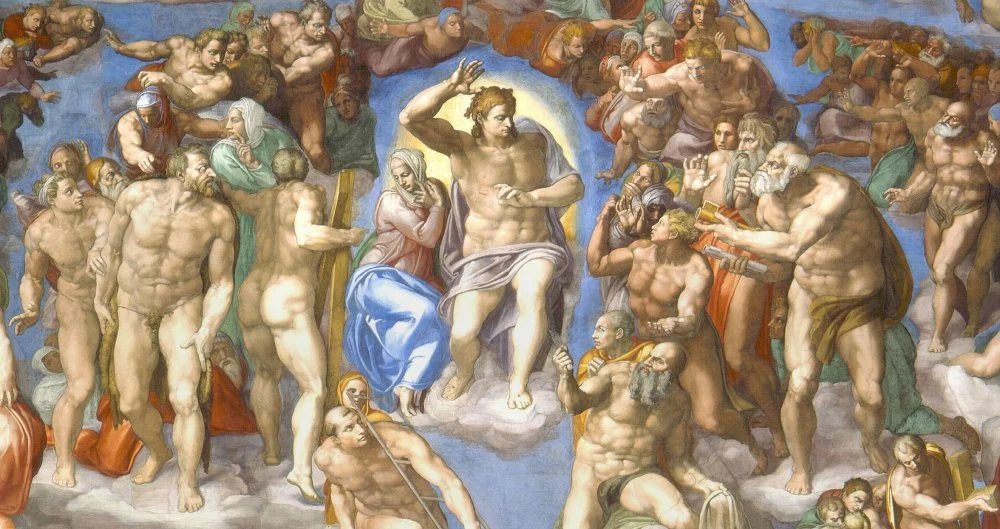

A fragment of the fresco "The Last Judgment" by Michelangelo. Christ in a purple toga. The Virgin Mary is nearby.Sistine Chapel, Vatican City, 1537-1541/Wikimedia commons

To Die for Purple

When emperors ruled Rome, wearing a purple toga was a risky move even for a rich and influential person. Only the emperor and high-ranking officials of his family or personal bodyguards had the right to wear purple. Anyone else who dared to do so could be accused of treason and executed. Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, in his book The Life of the Caesars, writes of Caligula: ‘After inviting Ptolemyi

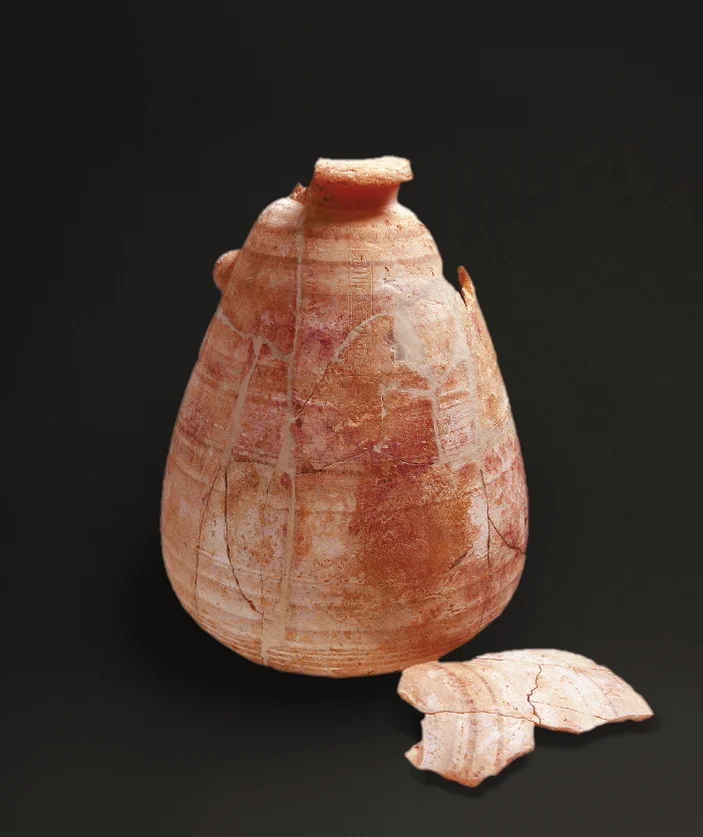

Alabaster jar with the name and titles of Darius I, king of Persia, in four languages

However, Michel Pastoureau notes: ‘Individuals could also own purple fabrics to use as furnishings: covers, hangings, curtains, carpets, and cushions. The richest individuals indulged themselves. In one of Horace’s Satires, written at the end of the first century [BCE], the poet mocks a certain Nasidenius, with his newly acquired but nonetheless fabulous wealth, who pushes ostentation and absurdity to the limit by having the table wiped with a purple towel (gausape purpureo) after a lavish feast.’

It is also noteworthy that the Persian king Darius I awarded his subjects with purple-painted ceramic vessels for special merits.

Born in the Purple

Byzantium, the Eastern Roman Empire, inherited its attitude towards purple from the ‘first Rome’. The word ‘porphyrios’ (meaning ‘purple’) became synonymous with the word ‘royal’. Byzantine empresses gave birth in the Porphyry Hall of the imperial palace. The Byzantine princess Anna Komnene, who was one of the first female historians ever, wrote about how the emperor ‘found the empress in the throes of childbirth, in the room set apart long ago for an empress’s confinement. Our ancestors called it the porphyra [Πορφύρα]— hence, the world-famous name porphyrogenitus [meaning purple-born].’

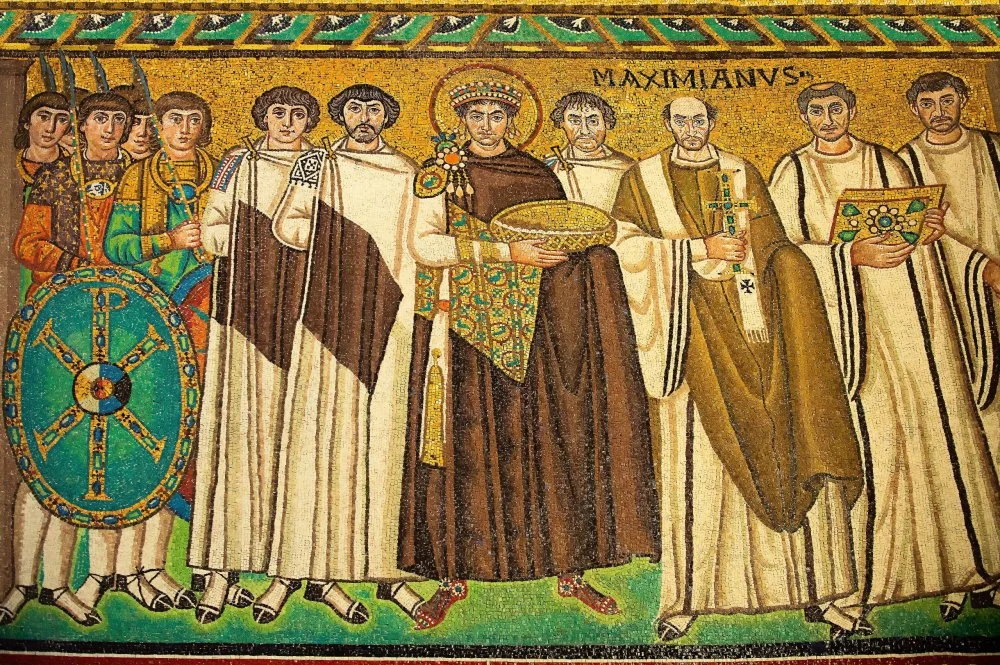

Emperor Justinian and his retinue. Mosaic of the Basilica of San Vitale. Ravenna, Italy, 6th century/Legion-Media/Alamy

‘This porphyra is a room in the palace built in the form of a complete square from floor to ceiling, but the latter ends in a pyramid. The room affords a view of the sea and harbour where the stone oxen and lions stand. Its floor is paved with marble, and the walls are covered with marble panels. The stone used was not of the ordinary kind, nor marble which can be more easily obtained but at greater expense; it was, in fact, casually acquired in Rome by former emperors. This particular marble is generally of a purple colour throughout, but with white spots like sand sprinkled over it. It was for this, I suppose, that our forefathers called the room “porphyra”,’ Anna Komnene notes in the Alexiad.

Byzantine Empress Theodora. Byzantine mosaics in the Basilica of San Vitale 547 AD 6th Century in Ravenn/Legion-Media/Alamy

It was Byzantium that had and retained the technology for producing the precious purple dye from shellfish. This meant that they remained the main producer and exporter of purple for the royal houses and clergy of Europe until the mid-fifteenth century.

Purple: A Casualty of War

After the Turks conquered Constantinople in 1453, the secret of the production of purple was lost. During the war, the Ottoman Empire destroyed the last workshops producing Tyrian purple. They then sold the remains of the pigment and dyed fabrics at such inflated prices that Pope Paul II, who was short of funds at the time, issued a decree in 1464 against using expensive Tyrian purple. Instead, the more affordable cochineal, derived from oak, was to be used for certain parts of the clerical vestments.

Despite this, purple did not disappear from the world of fashion, although it was somewhat faded and modified. Fabrics were dyed purple shades by mixing various red and blue dyes.

Purple as a Cure

The resurgence of the popularity of the color purple began in 1856, when eighteen-year-old college student William Henry Perkin unsuccessfully tried to synthesize the antimalarial drug quinine. He was about to pour the results of his unsuccessful experiment into the sink when he noticed a precipitate of a magnificent purple color in the flask. This was the first of the aniline dyes, mauvein.

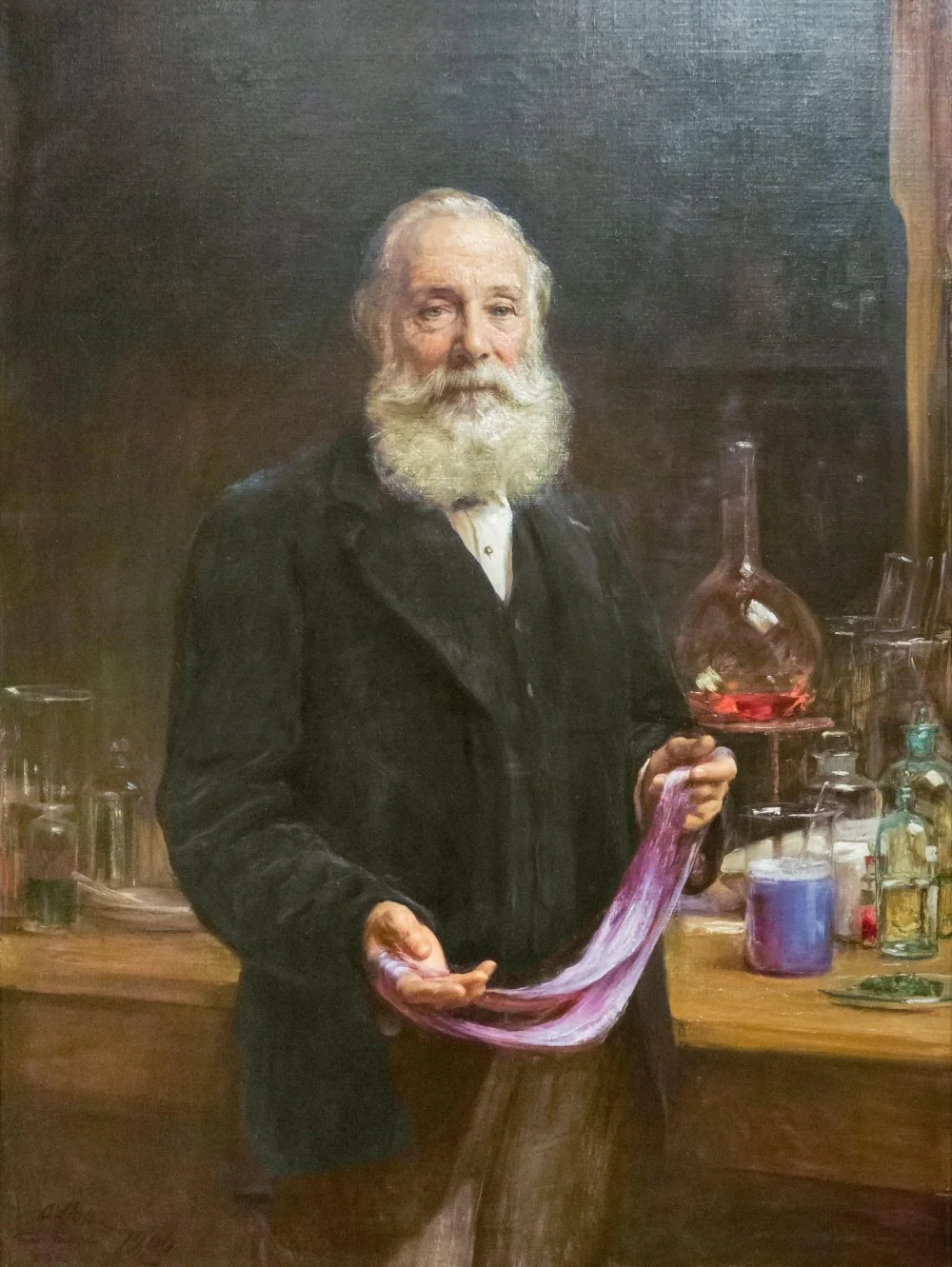

Sir William Henry Perkin by Sir Arthur Stockdale Cope 1906 © National Portrait Gallery, London/Legion-Media/Alamy

Despite his age, Perkin was a shrewd businessman. He immediately patented mauvein, and within a year, he had begun the commercial production of purple fabrics, persuading his father to invest and inviting his brothers to become partners in the factory.

The success of the new dyes was astounding, and purple quickly returned to world fashion. In 1906, William Henry Perkin was even knighted to honor the fiftieth anniversary of his discovery of mauvein.

What to read

Michel Pastoureau. Red: The History of a Color. Princeton University Pres, 2017.

Victoria Finlay. Color: A Natural History of the Palette. Random House, 2003.

Sir William Henry Perkin // Encyclopædia Britannica.