As the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth, a great wave of awakening surged through Kazakh intellectuals, sparking a passionate quest for knowledge. This outpouring of intellectual zeal led to an explosion of new magazines and newspapers being published in Kazakh, heralding the dawn of a new era in sharing culture. However, what these intellectuals wrote went beyond only spreading knowledge. Soon, a variety of publications emerged, covering topics like business, society, politics, art, and humor. Qalam invites you to explore snippets from Kazakh publishing culture and history, offering a glimpse into the important issues of the past.

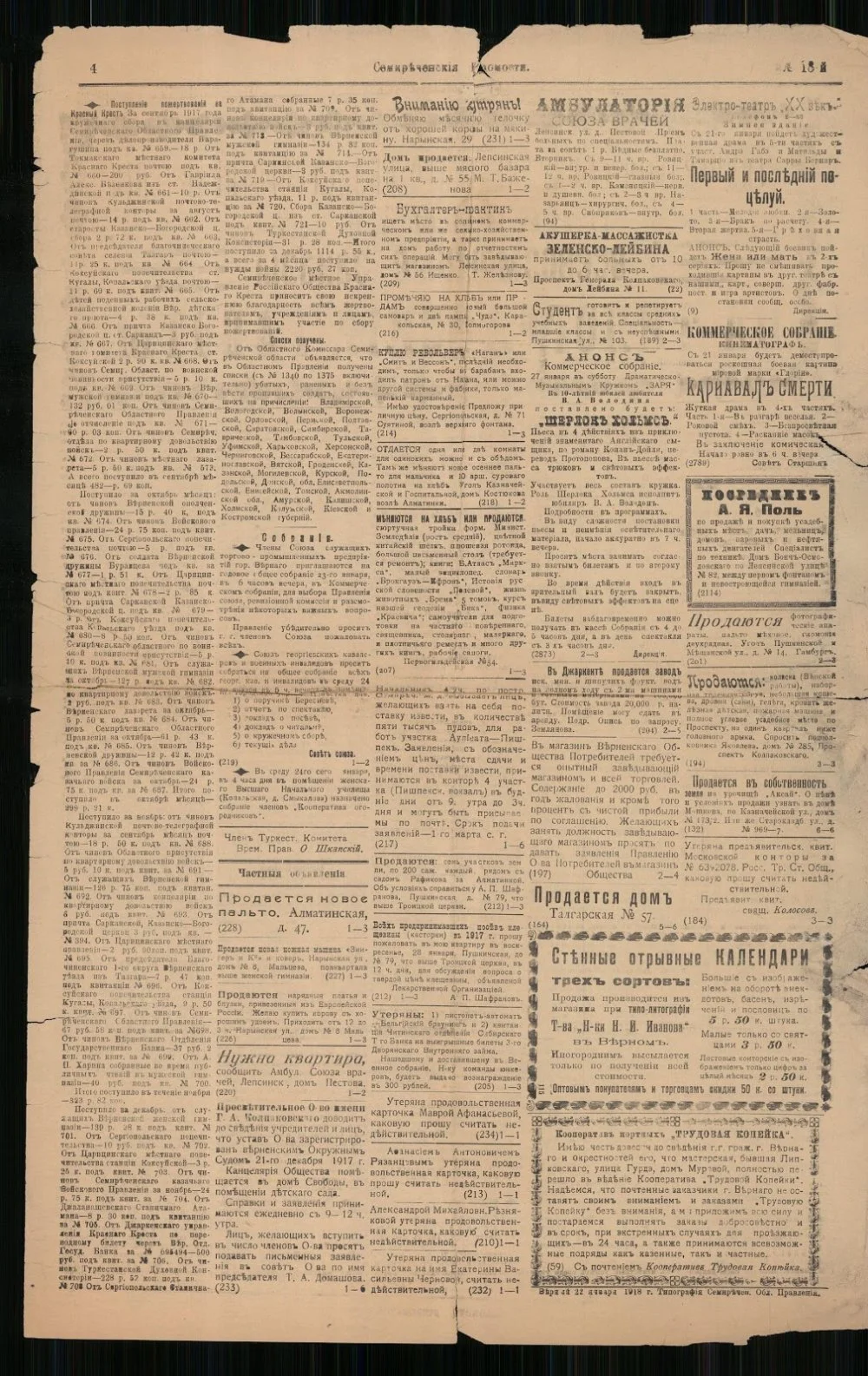

In a previous article, we discussed newspaper advertisements in Almaty from 1911. At that time, the pages of the Semirechensk Regional Gazette were filled with elaborate ads, posters, and numerous offers for various services. This surge in advertising was no coincidence, as the years leading up to World War I are considered some of the most prosperous in the history of the Russian Empire, affecting both the major cities and regional hubs like Almaty. However, a glance at the classified section from January 1918 reveals a stark contrast: a large portion of the ads now focus on trading valuable property for bread.

Semirechesnskie Oblastnye Vedomosti (Semirechye Regional Newspaper)/from open access

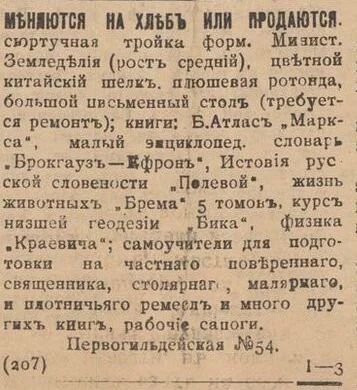

EXCHANGE FOR BREAD OR FOR SALE

A frock coat set from the Ministry of Agriculture (medium size), colorful Chinese silk, a plush cloak, a large writing desk (in need of repair); books: "Marx's Great Atlas," the small encyclopedic dictionary "Brockhaus and Efron," "History of Russian Literature," "Polevoy," "Brehm's Animal Life" (5 volumes), "Bik's Course on Elementary Geodesy," "Kraevich's Physics," along with self-study guides for training as a private attorney, priest, carpenter, painter, and other trades, plus various other books and work boots.

Semirechesnskie Oblastnye Vedomosti (Semirechye Regional Newspaper)/from open access

It's clear that the seller, offering ministerial uniforms and Chinese silk, comes from a higher social class. Yet people are willing to trade valuables such as a new samovar, children's coats, dresses, blouses, and more just for bread. Numerous ads also report the loss of ration cards. Meanwhile, the front page of the January issue of the Semirechesnskie Oblastnye Vedomosti carries an urgent warning from the city council:

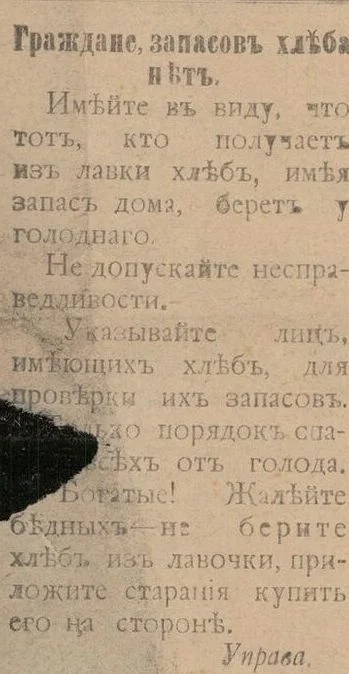

BREAD SUPPLIES EXHAUSTED

Citizens, be aware: those taking bread from shops while still having reserves at home are depriving the hungry. Do not tolerate this injustice. Report individuals who are hoarding bread so their stocks can be inspected. Only strict order will prevent widespread hunger. To the wealthy: show compassion for the poor—refrain from taking bread from local shops and seek to purchase it elsewhere.

City Council.

Semirechesnskie Oblastnye Vedomosti (Semirechye Regional Newspaper)/from open access

By January 1918, the situation in Almaty and across Semirechye had reached a critical point. Following the Bolshevik coup in October 1917, their influence had extended as far as Tashkent. However, in Semirechye, the Military Government, with Cossack support, seized power and pledged cooperation with the Alash-Orda government. At the same time, Bolshevik agitators were active throughout the city and region, and by March 1918, they had succeeded in establishing control over Almaty. This marked only the beginning of the Civil War, which would rage on for more than three years.

The Semirechesnskie Oblastnye Vedomosti was launched in 1870 in Almaty. The publication frequently covered world and national news, local events, crime reports, and advertisements, being printed in both Russian and Kazakh.