Змей, пожирающий младенца

Почему на эмблеме Alfa Romeo мы видим такие ужасы?

Эмблема Alfa Romeo/Getty Images

О змеях-людоедах, которых укротили итальянские аристократы

Знаменитая эмблема итальянской автомобильной марки Alfa Romeo в век новой этики нуждается если не в предупреждениях о триггере,1

Эволюция эмблемы Alpfa Romeo/Alfa Romeo Automobiles S.p.A.

В 1910, когда эту эмблему выбирали, она казалась более чем естественной. Миланская компания объединила в эмблеме герб города Милана — крест на белом фоне — и герб Миланского герцогства — ту самую змею. А закусывающая рептилия на гербе герцогства, известная в геральдике как Biscione (от лат. bestia — зверь), была заимствована с герба первых владык этого государства, семейства Висконти (правители Милана в 1277–1447 гг.). Позднее, когда прямая ветвь герцогов Висконти угасла, змею вместе с герцогством прибрал зять последнего Висконти, Франческо Сфорца. Так она вошла и в эмблематику миланских Сфорца.

Кровожадного змея на гербе Висконти объясняют в разных источниках несколькими мифами.

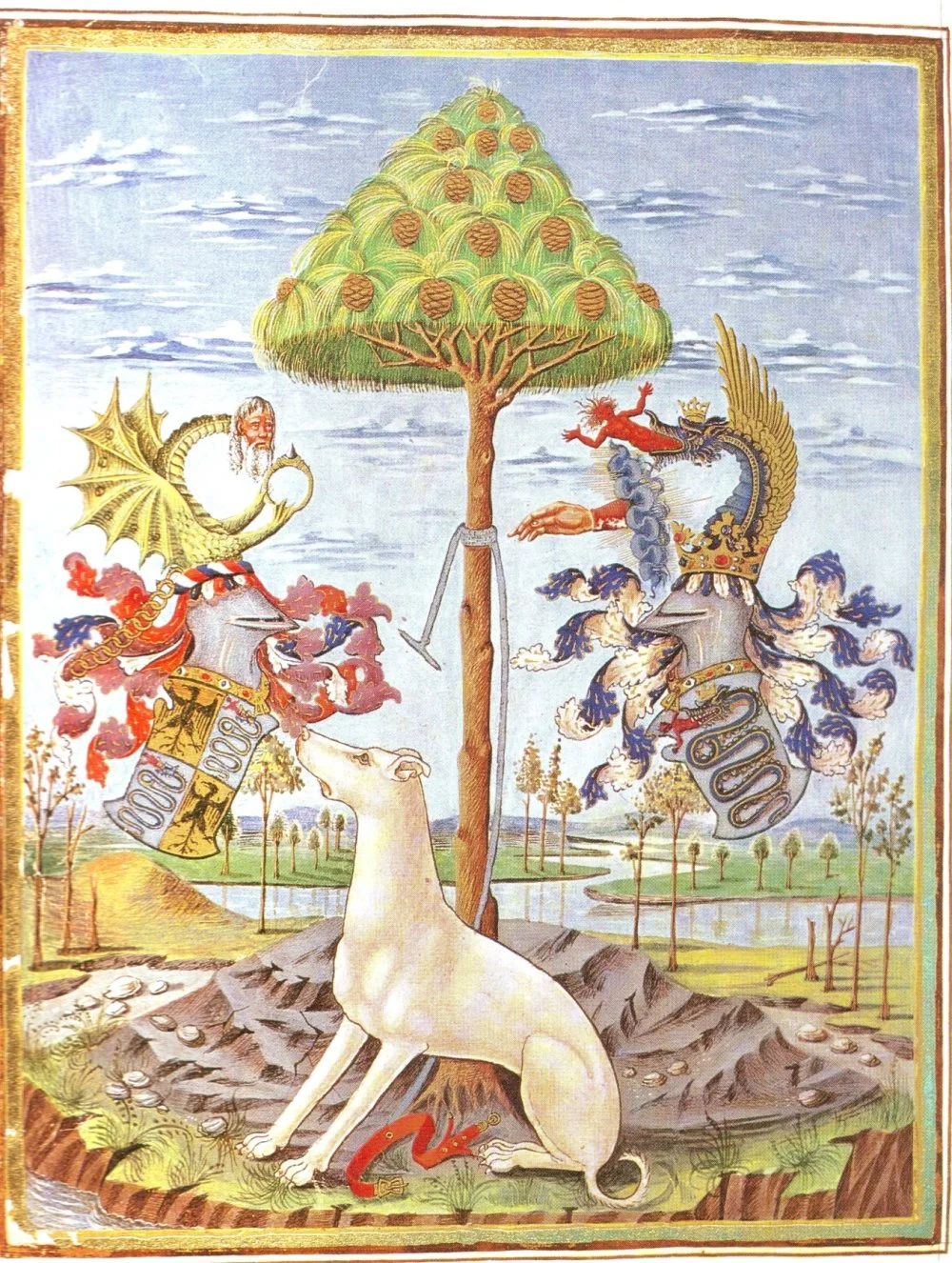

Герб Висконти. Королевская вилла Монцы. 18 век/Shutterstock

Миф первый. Бонифаций, владыка Павии, женится на Бьянке, дочери герцога Миланского. Пока Бонифаций сражается с сарацинами, его сына похищает и пожирает огромная змея. Вернувшись с войны, Бонифаций идет по следу змеи, убивает ее и извлекает из ее чрева чудесным образом выжившего младенца.

Этот популярный в народе сюжет, видимо, вызывал все же скепсис у общества более ученого, поэтому в старинных геральдических справочниках можно найти иное объяснение. В 1137 году Оттоне Висконти в крестовом походе сражается с неким сарацином, на чьем щите было издевательское изображение змея, пожирающего христианского младенца. Сарацина Висконти убил, щит его отнял, а змея разместил в своем гербе как напоминание о славной победе.

Гербы Висконти (справа) и Сфорца (слева) из кодекса «О сферах» 1469 г./Wikimedia Commons

Надо признаться, что убедительность данной версии даже ниже, чем первой. Теоретически во времена теплого климатического средневекового оптимума какой-нибудь рехнувшийся питон мог добраться до Милана и попытаться слопать там ребенка перед тем, как быть забитым лопатой (ну, или мечом). Но арабские бедуины, которых европейцы именовали сарацинами, уж точно не носили на своих щитах никаких гербов, тем более с запрещенными у мусульман изображениями людей и животных.

Так что приходится признать, что наиболее убедительной выглядит версия, которую в своей книге «Символическая история европейского средневековья» воспроизводит французский историк Мишель Пастуро:

«Первоначально Висконти были всего лишь правителями крошечного тосканского городка Ангьяри, чье название напоминает латинское anguis (“змея”). В середине 14 века, чтобы приукрасить свое происхождение, которое казалось не слишком уж благородным, Висконти создают героическую легенду, объясняющую их герб более возвышенным образом».

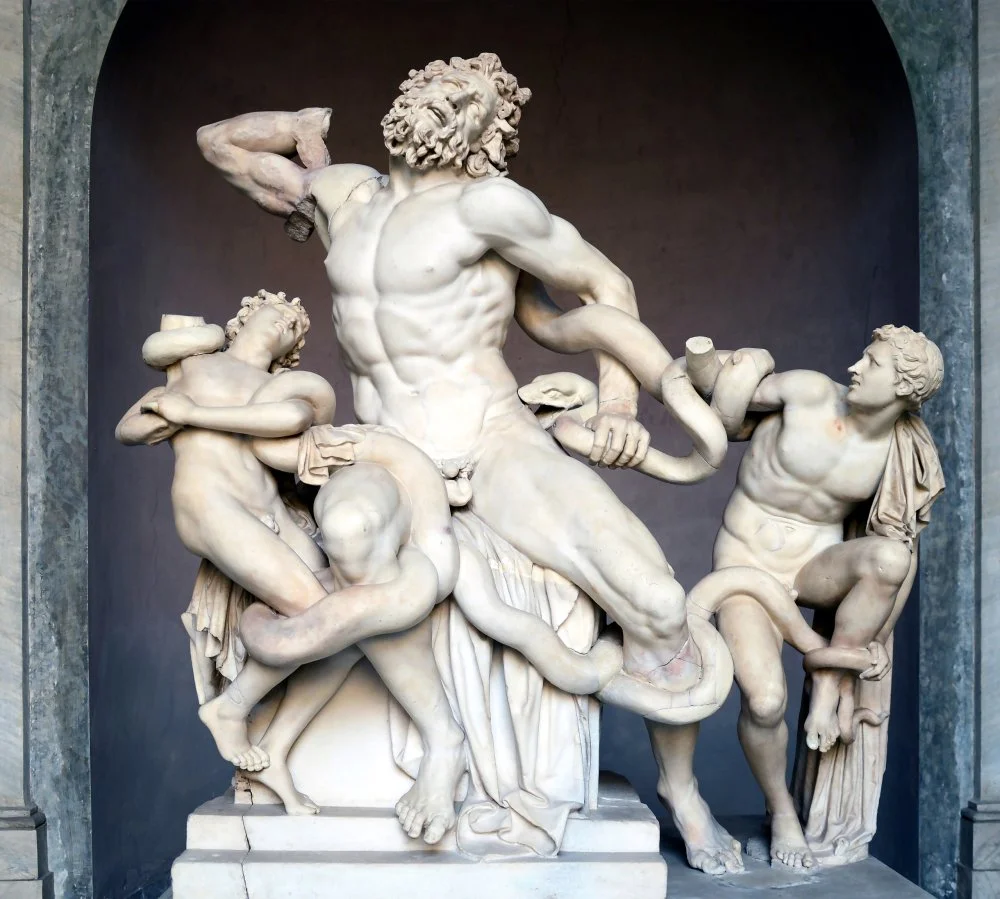

Лаокоон и его сыновья. Вт. пол. 1 в. до н. э./Wikimedia Commons

Казалось бы, змея не символизировала ничего хорошего. В Библии диавол искушает Еву в образе змея. Но это не единственная интерпретация. Младенец, обвитый змеей, — один из древнейших крито-микенских и даже индоевропейских символов. Он восходит к неолитическим культам поклонения Богине-матери, чьим символом также была огромная змея. Образ этот был многократно переосмыслен в мифах о младенце Геракле,2

ЧТО ПОЧИТАТЬ

Мишель Пастуро. Символическая история европейского средневековья. — Симпозиум, 2019.