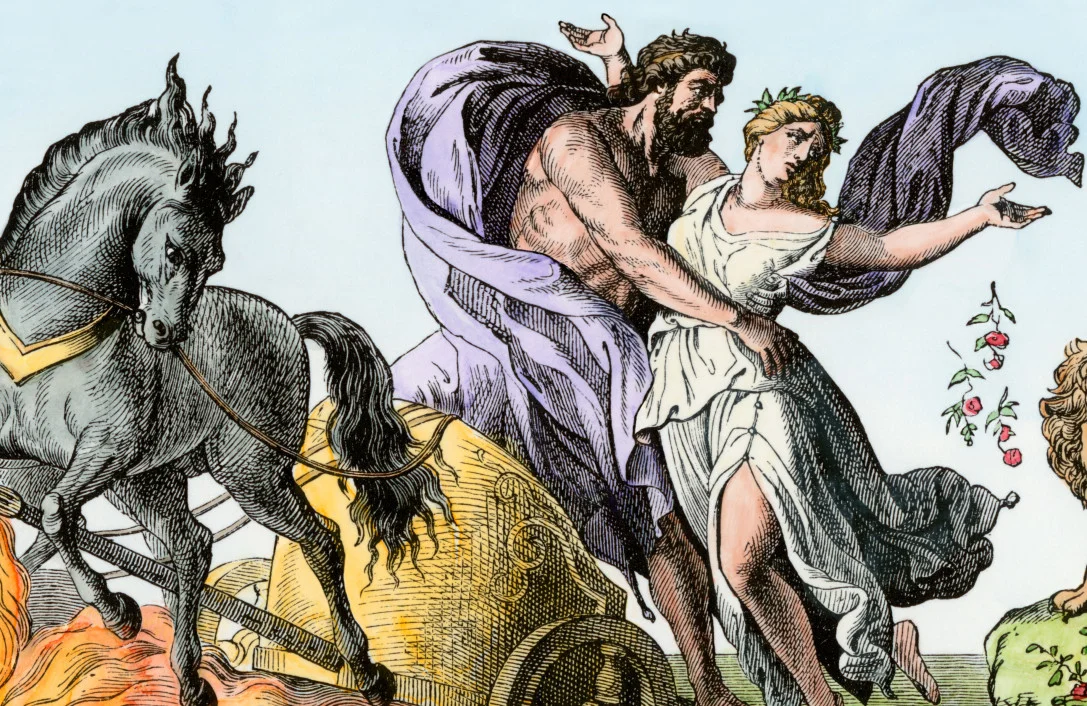

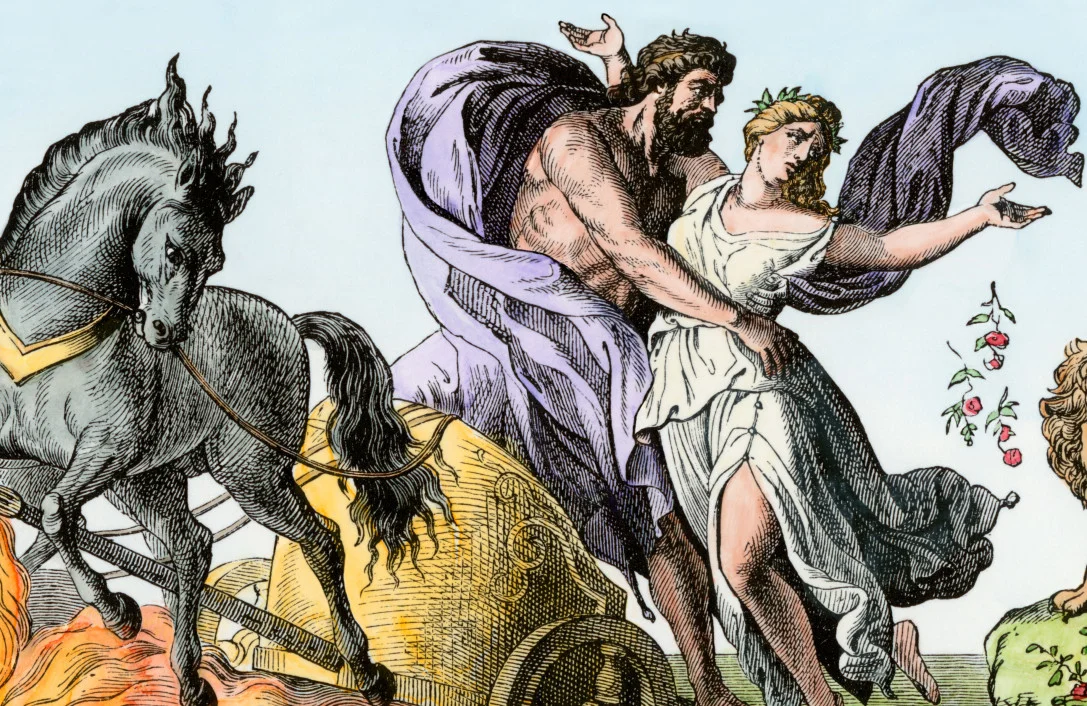

Pluto carries off Persephone to his Kingdom. 19th century/Alamy

Japanese god Izanagi and his wife Izanami/Alamy

Adam and Eve/Alamy

Pluto carries off Persephone to his Kingdom. 19th century/Alamy

Japanese god Izanagi and his wife Izanami/Alamy

Adam and Eve/Alamy