A Serpent Devouring a Child

The story behind the horrors in the Alfa Romeo logo

The logo of Alfa Romeo/Getty Images

On Man-Eating Serpents Tamed by Italian Aristocrats

In this age of new and evolving ethical standards, the logo of the famous Italian automotive brand Alfa Romeo needs an explanation, if not a clear trigger warning.1

Alfa Romeo logo/Fiat S.p.A./Alfa Romeo Automobiles S.p.A.

In 1910, when this logo was chosen, it seemed like a normal, natural choice. The Milanese company incorporated the coat of arms of the city of Milan—a cross on a white background—and the coat of arms of the Duchy of Milan—a serpent. The serpent devouring its prey, usually a baby, on the coat of arms of the duchy, known in heraldry terms as the Biscione (from Latin bestia, meaning beast), was borrowed from the coat of arms of the Visconti family, the first rulers of Milan from 1277 to 1447. Subsequently, when the direct line of the Visconti dukes faded away, the serpent, along with the duchy, was adopted by the son-in-law of the last Visconti, Francesco Sforza. Thus, it became part of the symbolism of the Milanese Sforza as well.

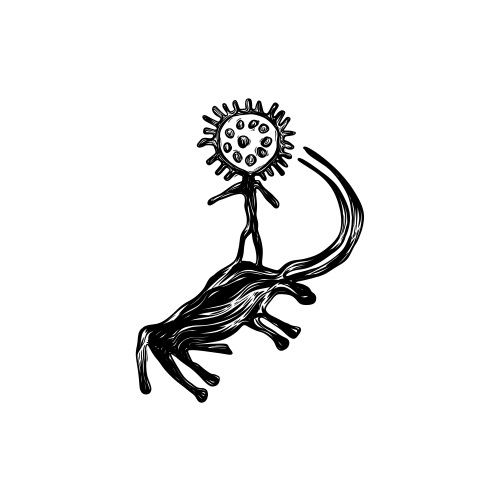

Various myths offer an explanation for the bloodthirsty serpent in the Visconti coat of arms.

Image depicting the coat of arms of the house of Visconti, Monza Gardens of the Royal Villa/Shutterstock

The first one states that Bonifacio, the lord of Pavia, married Bianca, the daughter of the Duke of Milan. While Bonifacio was fighting the Saracens, his son was abducted and devoured by a huge serpent. Upon returning from the war, Bonifacio followed the trail of the serpent, killed it, and miraculously retrieved the child, alive, from its belly.

This popular folk narrative caused skepticism among the more educated circles, and hence, another explanation can be found in ancient heraldic sources. In 1137, during a crusade, Ottone Visconti battled a certain Saracen whose shield bore the mocking image of a serpent devouring a Christian child. Ottone killed the Saracen, took his shield, and incorporated the serpent into his coat of arms as a reminder of his glorious victory.

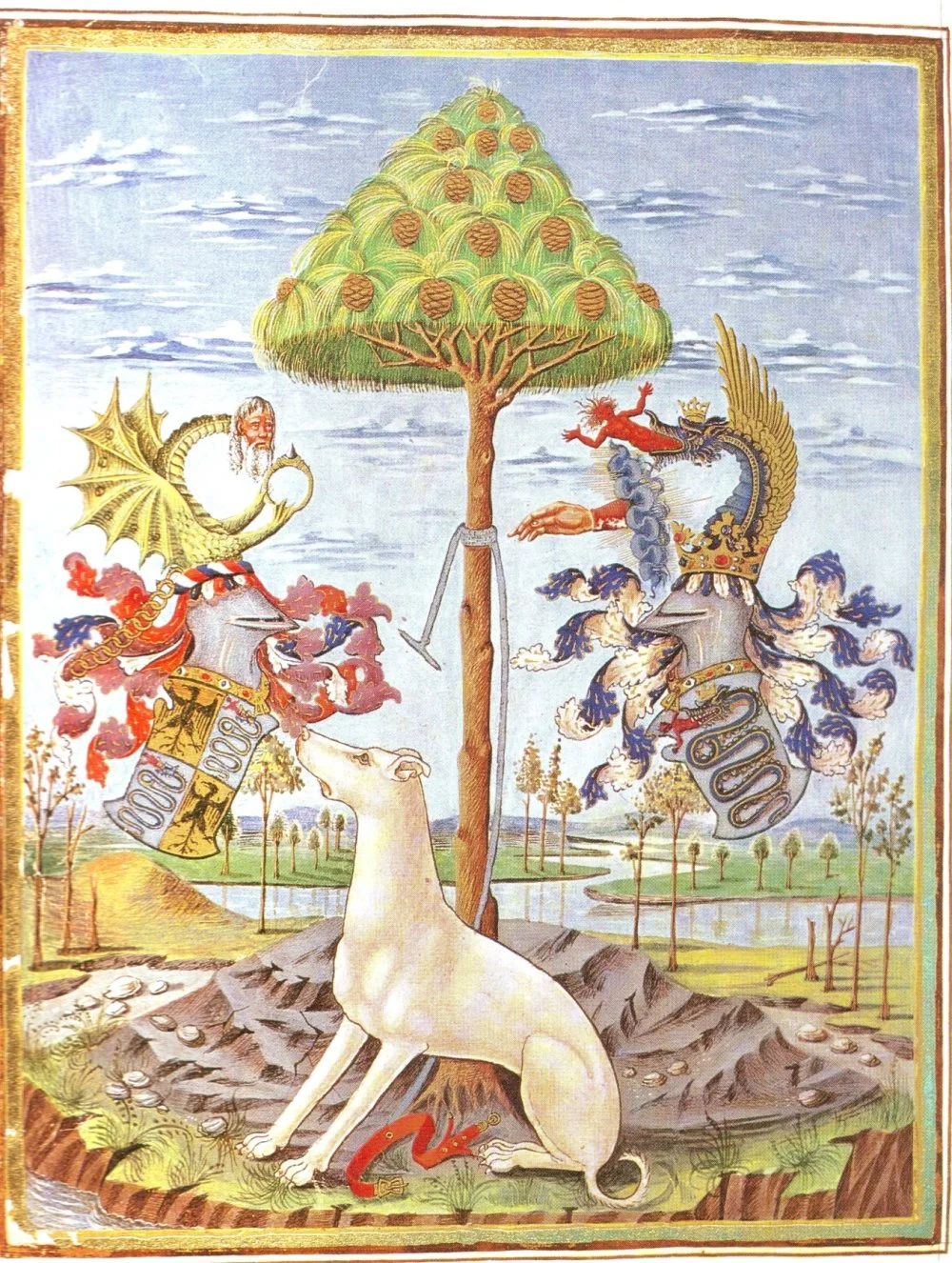

Codex de sphaera (estense) - 1469. Allegory of Sforza family's Coat of Arms. Biblioteca Estense in Modena, Italy/Wikimedia Commons

It must be admitted that the possibility of this version taking place is even lower than the first. Theoretically, during the warm climate of the medieval optimum, some crazed python could have made its way to Milan and attempted to devour a child there before being dispatched with a shovel (or a sword). But Arab Bedouins, whom the Europeans called Saracens, certainly did not bear any coats of arms on their shields, let alone ones with depictions of humans and animals, which were forbidden by Muslim beliefs.

Thus, it must be acknowledged that the most convincing version is the one reproduced in the book Symbolic History of European Medievalism by the French historian Michel Pastoureau:

‘Originally, the Visconti were only rulers of the tiny Tuscan town of Angiari, whose name recalls the Latin anguis (“snake”). In the mid-fourteenth century, to embellish their origins, which seemed not too noble, the Visconti created a heroic legend explaining their coat of arms in a more exalted manner.’

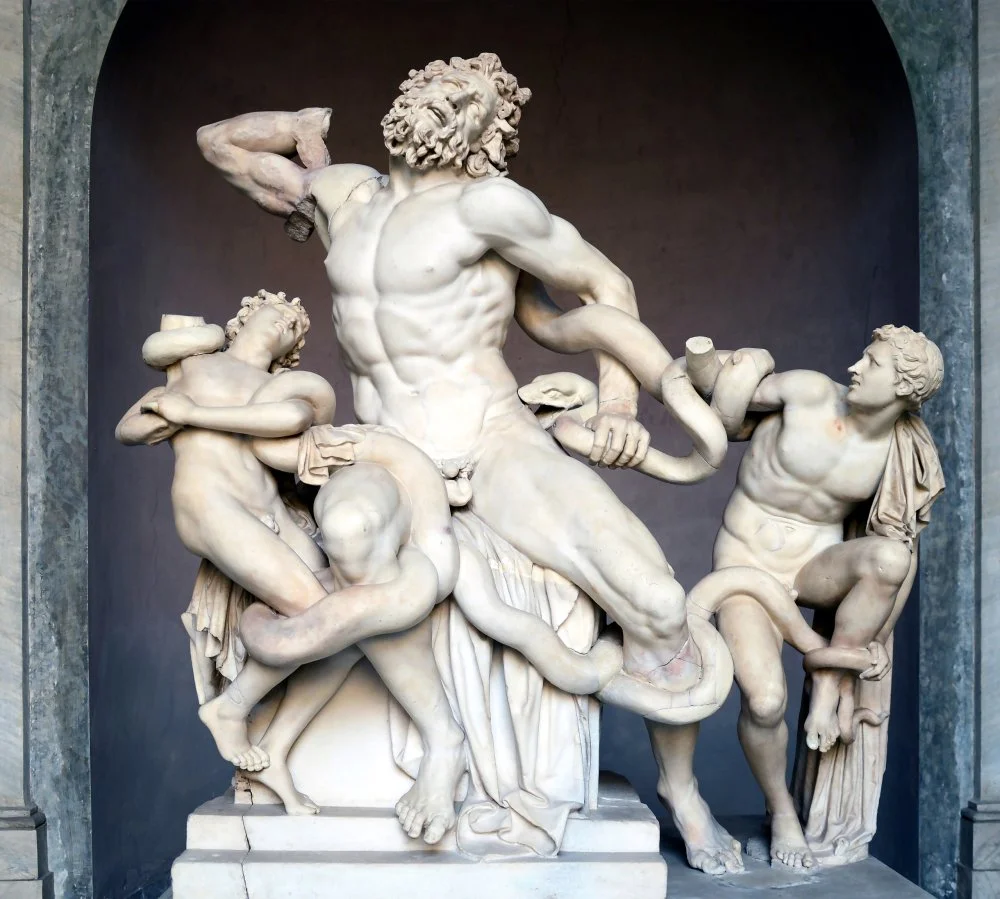

Laocoön and his sons, also known as the Laocoön Group /Vatican Museums/Wikimedia Commons

However, it would seem that the serpent symbolized nothing good. In the Bible, the devil tempts Eve in the form of a serpent. And this is not the only interpretation of serpents. The child wrapped in a serpent is one of the oldest symbols of the Minoan-Mycenaean and even Indo-European cultures. It dates back to Neolithic cults who worshiped the mother goddess of nature, whose symbol was also a huge serpent. This image was reinterpreted multiple times in myths about the child Hercules,2

References

Pastoureau, Michel. Symbolic History of European Medievalism. Symposium, 2019.