In Norse mythology, it has long been prophesied that when Ragnarök, or the end of the world comes, the wolf Fenrir will be unchained, the sky will darken, and a ship of the dead will appear from the sea. But what exactly influenced the ancient Scandinavians’ apocalyptic visions—and what if Ragnarök has already come to pass?

The Climate in World History

What do you, I, the Byzantine Emperor Justinian, the medieval Germans, and the ancient Greeks have in common? It’s just one thing—we are all very dependent on the climate. In the year 2024, abnormal heat waves and severe frosts around the world have caused the harvests of various crops to fail or deteriorate, and the retail prices for these items went up exponentially. If this is possible in the age of technology, what must have been the impact of climate change on traditional agricultural societies?

Throughout human history, the climate has moved between cold and hot periods, but it is impossible to speak of them as cyclical as scientists have not been able to find a periodicity, or a regular pattern, in which a cold period is replaced by a warm one. For example, we live in very warm times, although only 150 years ago the planet was experiencing the Little Ice Age.

Winter Landscape with Ice Skaters (1608) by Hendrick Avercamp/Wikimedia commons

n the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, historians first wondered if the climate in ancient times was different from today’s. They began their study comparing the flowering times of Mediterranean plants described in historical texts and what they could see around them. They found that the plants blossomed at the same time before and during the study and, thus, concluded that the climate had not changed much.

However, this analysis was based on a time when the Little Ice Age was coming to an end and the climate was much colder than it is today. Based on this information, twenty-first-century scientists believe that the Mediterranean basin was significantly colder in ancient times than it is today. In the winter, Athens experienced long rains, sometimes interspersed with snow. Viticulture, considered an indigenous Italian occupation, did not spread to the north of Naples for a long time. Even more strikingly, the records of the Roman historian Titus Livius even mention the Tiber freezing over, which is hard to imagine today.

Winter Landscape with the Tiber and the Ponte Molle Rome is a painting by Willem Schellinks/Wikimedia Commons

By 200 BCE, however, the Roman Climatic Optimum (or the Roman Warm Period) had been established: the Mediterranean had forgotten about snowfalls, frozen rivers, crop failures, and famine. Even in the Alps, the snow cover decreased, making it easier for Roman troops to cross the mountains. At the same time, the Romans began cultivating heat-loving grapes in Britain and Germany. The average temperatures were similar to today’s climate, and the pleasant weather benefited not only the Roman Empire but also the barbarians: their numbers increased significantly during the years free from prolonged famine.

The Year Without a Summer

In the fourth century, the Roman Climatic Optimum was sharply replaced by cooler weather. Winters were on average 1–2°C colder than they are today. This may seem like a very small difference, but on a planetary scale, it is enough to make the first noticeable changes.

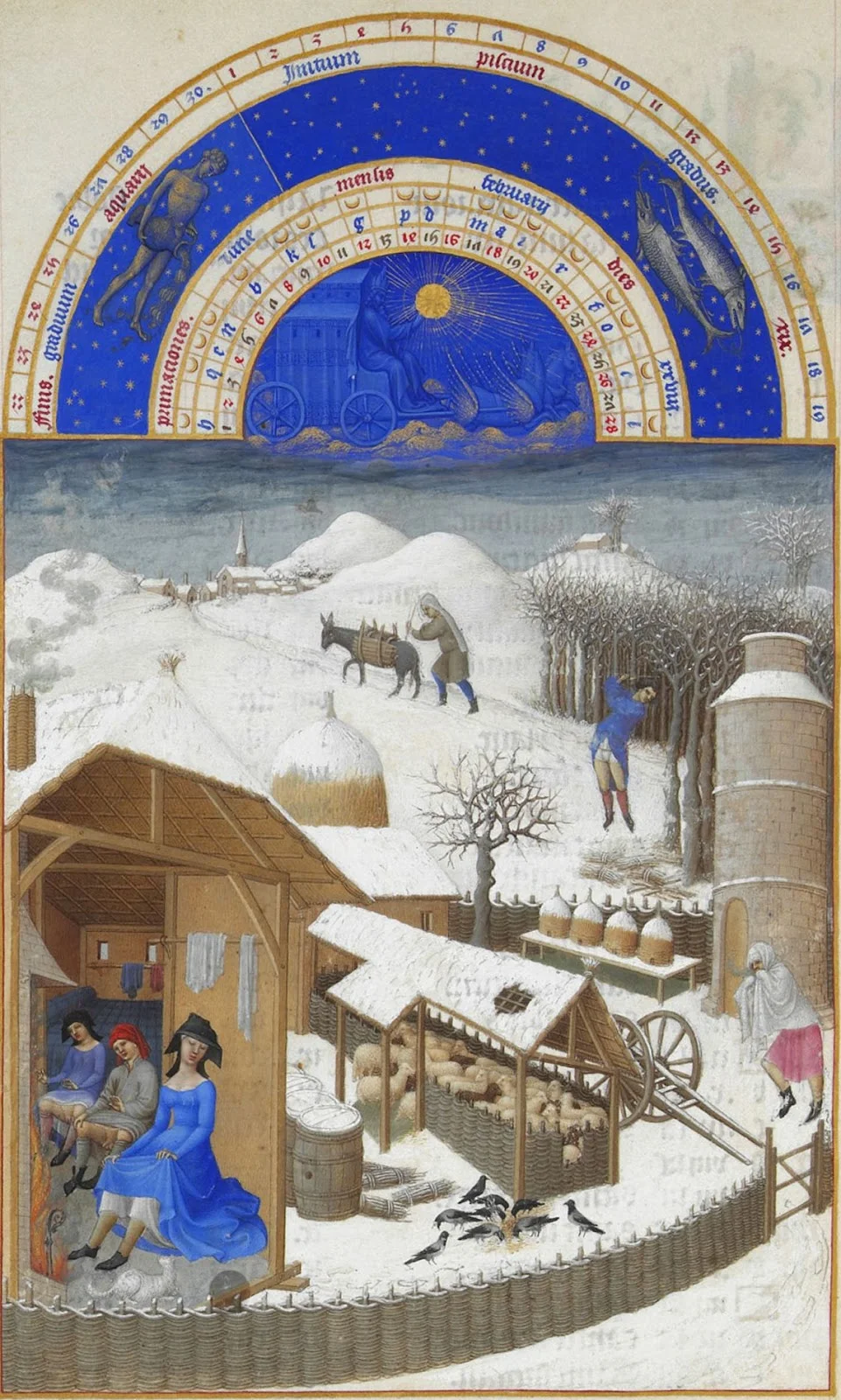

"February" from the calendar of the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1412–1416/Wikimedia commons

This cooling was a natural process. But in 535–36, a cataclysmic event triggered a real climatic catastrophe: the temperature in Europe fell more sharply than it had in the previous 2,000 years.

Most scientists attribute this fall in temperature to the eruption of one of these volcanoes: Krakatoa, Ilopango, Rabaul, or El Chichón. We do not know for certain which of these volcanoes caused the cooling since all of them exhibited significant activity during this period. Therefore, scientists sometimes speak of a series of eruptions that occurred at the same time.

An 1888 lithograph of the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa. 1888 Image published as Plate 1 in The eruption of Krakatoa, and subsequent phenomena. Report of the Krakatoa Committee of the Royal Society (London, Trubner & Co., 1888)/Wikimedia Commons

After the eruption (whichever it may have been), the ash rose into the stratosphere, where it formed a dry fog, an aerosol of sulfuric gases, which could trap the sun’s rays and remain in the atmosphere for a long time.

Plague in Egine by Gérard Audran. ca 1698-1703/Wikimedia commons

The popular hypothesis is that the eruption caused a volcanic winter. For at least a decade, the sun dimmed and no longer warmed the Earth. As a result, the average temperature dropped significantly, which was noticed not only in the Mediterranean but also in other parts of the world. This is what historians of the time wrote about the ‘year without a summer’:

Procopius of Caesarea in the History of the Wars: ‘During this year a most dread portent took place. For the sun gave forth its light without brightness . . . and it seemed exceedingly like the sun in eclipse, for the beams it shed were not clear.’

John of Ephesus in Ecclesiastical History: ‘The sun became dark and its darkness lasted for eighteen months. Each day, it shone for about four hours, and still this light was only a feeble shadow. Everyone declared that the sun would never recover its full light again.’

St Sebastian pleading for the life of a gravedigger afflicted with plague during the 7th-century Plague of Pavi/Wikimedia Commons

The crop failures, famine, cold, and lack of sunshine significantly worsened the lives of people all over the planet. Add to this the Justinianic Plague that began in 541, as well as repeated references to pestilence in Irish and Chinese sources, and it becomes clear why it seemed like the end times had arrived for many historians of that era.

What Was Happening in Scandinavia?

At this time, the cooling in northern Europe was much more pronounced and prolonged than in the Mediterranean. The Scandinavian lands, which had never been very fertile, suffered greatly. Livestock starved, and the people starved with them.

The Migration Period, also known as the Barbarian Invasions, which began shortly before the disaster, affected the region as well. In the fifth century, warlike tribes, such as the Angles, Jutes, and Saxons, set out for the British Isles, while the Frisians moved into what is now the Netherlands. Scandinavia was noticeably deserted during this period: people began to settle further away from each other, each concentrating on their own households, and a vacuum appeared in the realms of military and political power. But soon the Angles, Saxons, Jutes, and Frisians were replaced by another Germanic tribe, the Heruli.

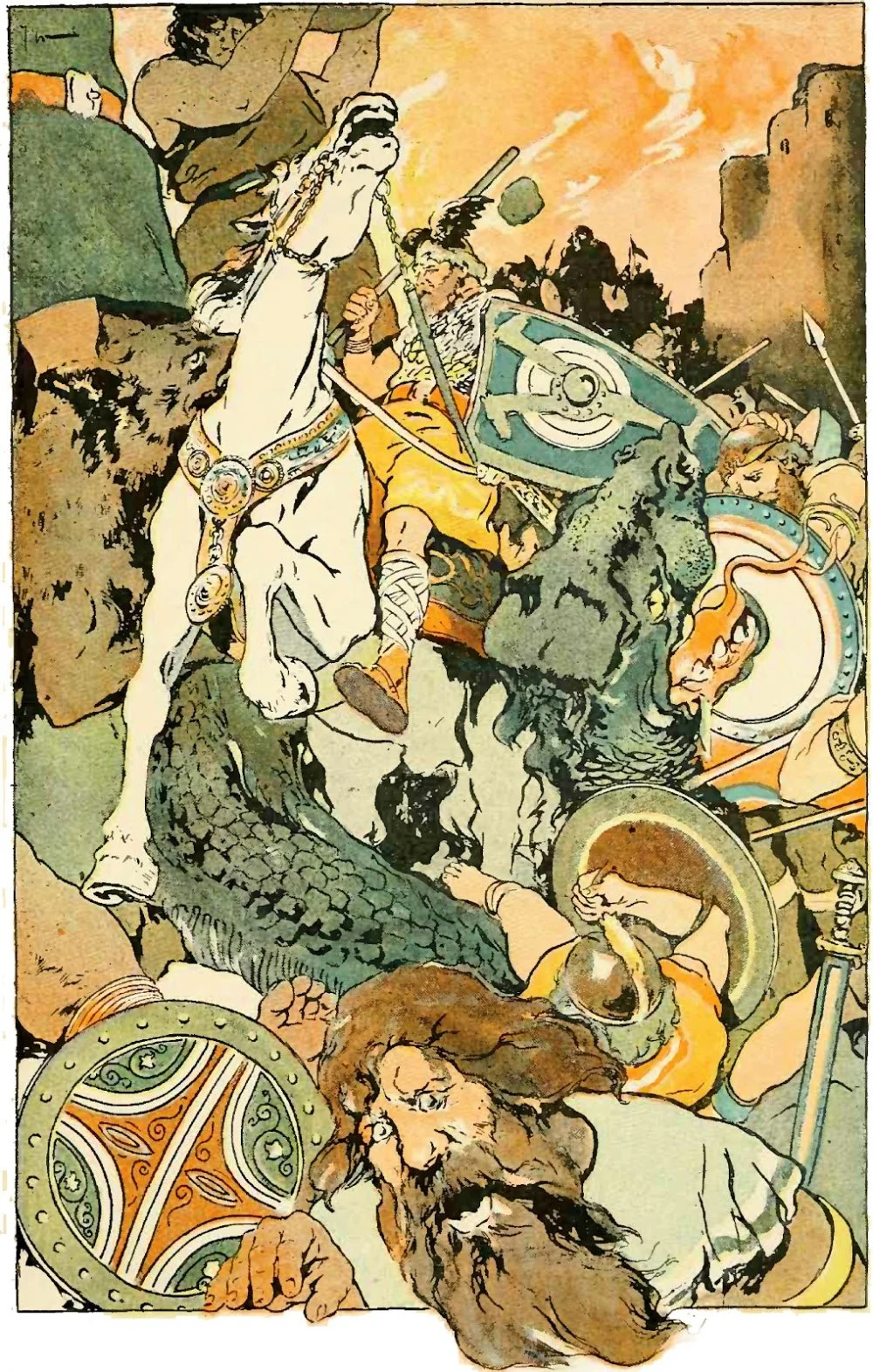

Then the awful fight began by George Wright Published in 1908 Mabie, Hamilton Wright. 1908. Norse Stories Retold from the Eddas. Dodd, Mead and Company, New York/Wikimedia Commons

For most of their history, the Heruli were involved in brigandry, piracy, and mercenarism. Failing to establish a state of their own, they moved back to the north, where they occupied the power vacuum in Scandinavia. Their culture and customs were quite different from the local traditions. For example, the Heruli brought with them the Sarmatian custom of building high burial mounds and burying their dead in boats.

Figures preparing the Sutton Hoo ship burial/ Craig Williams/British Museum

And along with the changes in burials came changes in religion. For example, before the arrival of the Heruli, many rituals in Scandinavia were performed with the participation of priests. But after that, the pagan priesthood began to play a much smaller role in the lives of the Northmen.

A group of rich burial sites date to this period. In addition to personal belongings, they contained bracteates, flat coins minted on one side only. The main thing about these coins was that they were not used as money but as amulets and heirlooms. They were not only meant to protect their owners but also symbolized a connection to a person’s ancestors.

The Funen bracteate (DR BR42 = DR IK58), found in Funen, Denmark. The runic inscription is read as: houaz laþu aaduaaaliia a– or alternatively houaz / laþu aa duaaalii(a) / al(u). According to the display at the National Museum of Denmark, houaz is interpreted as "The High One", a name of Odin/Wikimedia Commons

In addition to bracteates, the hoards from this period include many gold ritual sheaths, bracelets, handles, and other objects used in ceremonies and sacrifices. The burials were so rich that the volume of gold alone could reach 12 kilograms, as was the case in the Tureholm Treasure.

A selection of Viking silver from the Cuerdale hoard in the British Museum. Buried in around 905, found in 1840/ British Museum/JMiall/Wikimedia Commons

One hypothesis is that this is how the ancestors of modern Scandinavians appealed to the gods, sending them more and more ritual objects, asking for help and hoping for protection from famine. However, the cooling process persisted for much longer than expected and this, along with changes in social structures and religious beliefs, led the Scandinavians to an idea that was unprecedented at the time: the gods were dead.

The Twilight of the Gods

The myth of Ragnarök, traditionally translated as ‘the twilight of the gods’, tells of the destruction of all living things. The key role in this is played by Fimbulvetr, the mighty winter. The myth is first known from Gylfaginning (The Beguiling of Gylfi), an epic written in the thirteenth century by Snorri Sturluson, the author of most of the famous sagas of that time. He lived after the end of the cooling period and based his texts on legends that had been handed down from generation to generation for centuries. According to the story, the konung (king) and sorcerer Gylfi had a vision sent to him by the Æsir.i

Gylfi is tricked in an illustration from Icelandic Manuscript, SÁM 66 In the Prose Edda, Gylfi, King of Sweden before the arrival of the Æsir under Odin, travels to Asgard, questions the three officials shown in the illumination concerning the Æsir, and is beguiled. 18th-century Icelandic manuscript/Wikimedia Commons

First will come the winter called Fimbulvetr. Snow will drive in from all directions; the cold will be severe and the winds will be fierce. The sun will be of no use. Three of these winters will come, one after the other, with no summer in between.

A scene from the last phase of Ragnarök, after Surtr has engulfed the world with fire (by Emil Doepler, 1905). The surrounding text implies that this is Ásgarðr (Asgard) burning. Published ca. 1905 /Wikimedia commons

The mighty winter does not come of its own accord because, according to Scandinavian myth, it comes only after the death of Baldr, the god of spring. And then, a series of terrible events begins. First the long winter comes, then the wolf Fenrir is freed from his fetters, and then the sun is stolen by a monster. This completely echoes the climate catastrophe when the sun disappeared for a long time! However, this story is as much about climate change as it is about the disruption of the usual order of things. In times of cold and famine, ancestral norms decline, family feuds begin, and traditional rituals become invalid. Something similar probably happened in Scandinavia in the sixth century. On the one hand there were noticeable climatic changes, on the other hand the Heruli came in and changed the usual way of life of the Scandinavians.

Ragnarök (Motif from the Heysham Hogback) (by W. G. Collingwood, 1908)/Wikimedia Commons

The pagan worldview, however, is cyclical: death is followed by life. According to the legends, after Ragnarök and the death of most of the gods, two sons of Thor and two sons of Odin would be left alive to build a new world. And there would be two humans with them , a man and a woman—the new Adam and Eve.

And whether you believe it or not, something like that actually happened. In the tenth century, the Medieval Warm Period began. During this time, the population of cities began to grow again. The Vikings could now afford to undertake long voyages, and it was then that their settlements in Greenland appeared.

The last written records of the Norse Greenlanders are from an Icelandic marriage in 1408 but were recorded later in Iceland, at Hvalsey Church, which is now the best-preserved of the Norse ruins/Wikimedia Commons

Various historical sources mention vineyards not only in the south but also in the north of Europe, as it had been before the cooling. Snorri Sturluson’s contemporaries in the thirteenth century probably feared the return of dark times when they passed on the legends of the great cold, reflected in the myth of Ragnarök.

Odin and Fenrir, Freyr and Surt (by Emil Doepler, 1905)/Alamy

The myth of the mighty winter, of cold and hunger, is so widespread and appealing to mankind that it appears in many modern pop culture stories as well. Indeed, it sees mention in, among others, J.R.R. Tolkien’s monumental work The Lord of the Rings. Two hundred years before Frodo was born, the long winter came to Middle Earth: ice and snow froze over the land and made travel impossible, and Sauron, the dark lord, took advantage of this to attack the kingdom of Gondor. This familiar plot can also be seen in The Chronicles of Narnia by Tolkien’s friend C.S. Lewis, in which the White Witch wants to subjugate Narnia by plunging it into eternal cold, bringing monsters with it. At the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first, a series of books was published in which there are frequent warnings such as ‘Winter is coming!’ This phrase, and indeed plot point, was famously used by George R.R. Martin as an important leitmotif of the entire A Song of Ice and Fire series. While the great houses struggle for power, the Night King approaches from the North, bringing with him the Always Winter that will not spare either hero or villain.

Susan , Peter (WILLIAM MOSELEY), Lucy (GEORGIE HENLEY), and Edmund (SKANDAR KEYNES) in a scene from THE CHRONICLES OF NARNIA: THE LION, THE WITCH AND THE WARDROBE, directed by Andrew Adamson/Alamy