King Solomon’s Sad Monster

How a Centaur Befriended Peasants

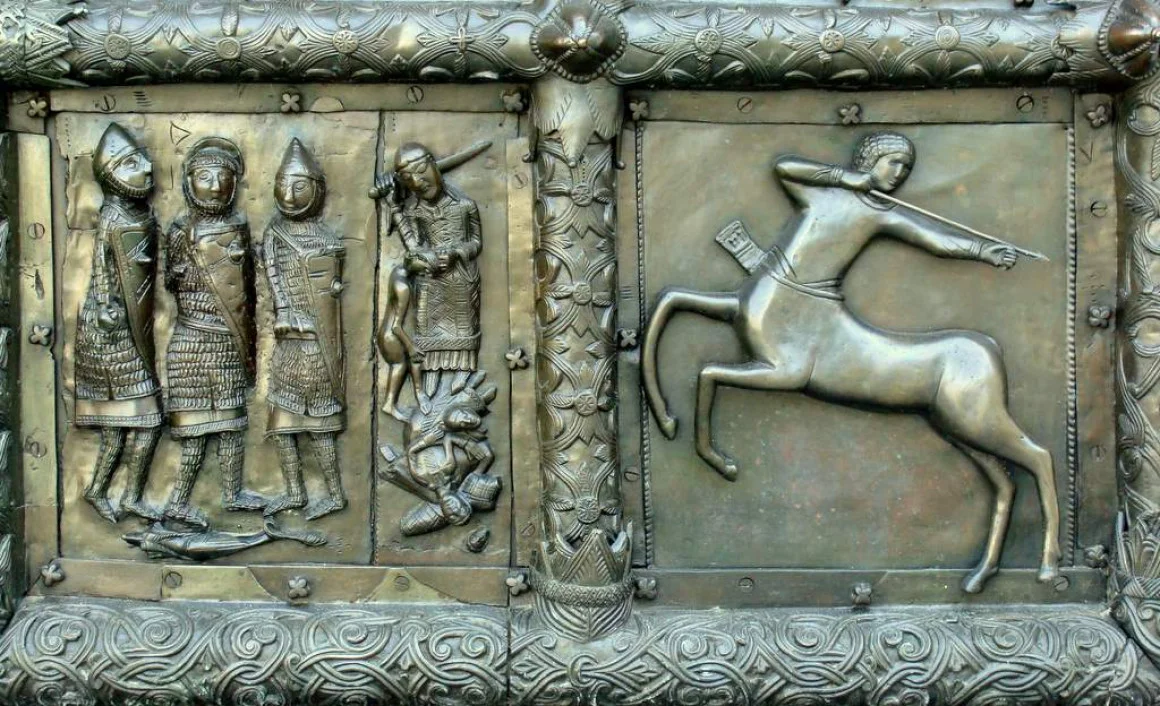

Magdeburg Gate of St. Sophia Cathedral in V. Novgorod/Wikimedia Commons

People often engage in wild conspiracy theories that challenge the limits of reason. Theories like, for example, that it was the Queen of England who put a contract out for Princess Diana, or that cancer can be cured by acupuncture. But sometimes, it is cute to believe in something absurd.

In the Middle Ages, the Slavs of southern and eastern Europe often learned about Christianity not as much from the Bible (because few people were literate in those days) as they did from free retellings of the Old Testament. These versions customarily contained entertaining, fantastic additions, usually taken from Byzantine texts, to brighten up a long winter evening with different kinds of stories. One such apocryphal text is the Palea, a collection of theological works from the ninth to the fifteenth centuries, consisting of mostly loose and expanded translations of Greek sources incorporating Greek versions of Jewish legends.

It is in this text that we find the first reference to Kitovras, who became a popular character of Slavic folklore. Kitovras (a distorted form of kentaurus, meaning ‘centaur’) was a wise creature who lived in the time of King Solomon. Half-man, half-beast, he was a magician and a prophet. He was described as having the body of a horse, lion, or dog, often with wings, sometimes with three faces, sometimes with six tongues, flaming eyes, and other remarkable signs of his extraordinary nature.

In traditional folk art, Kitovras usually looks rather sad—and there are reasons for this. In the most popular version of the myth, told in the Tales of Solomon and Kitovras, Kitovras was captured by Solomon in battle and subjugated to him forever. Once, the king needed the advice of a magical sage in a hurry, and Kitovras, having received the order by a messenger, ‘meekly walked’ to Jerusalem to the king’s palace.

Kitovras on the white stone carving of St. George's Cathedral (1230-1234), Yuryev-Polsky, Vladimir region / Wikimedia Commons

Kitovras had an interesting peculiarity: he could ‘walk only in straight paths, but not in crooked ones’. Whether his mind was so straight or his body so long and inflexible that he could only move in a straight line, the king ordered all buildings in Kitovras’s path to be demolished.

However, right in Kitovras’s path was the home of a poor widow, and the unfortunate woman wept and begged the guards not to destroy her dwelling. She said, ‘Sir, I am a poor widow. Do not humiliate me!’ Kitovras, hearing her pleas, took pity on her and tried with all his might to get around the hut, breaking a rib in the process. ‘A good word breaks a bone,’ Kitovras sighed. This phrase became a proverb that means that asking for something is often more reasonable than demanding it, and politeness and kindness are often more effective than aggression.

The image of the mighty and merciful Kitovras was very popular among Slavic peasants—the long half-man, half-beast decorated chests, spinning wheels, and dishes in village houses until the early twentieth century.

Kitovras. Image from the Collection of the Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery, scribe Hieromonk Efrosin, second half of the 15th century/Wikimedia Commons

Incidentally, some researchers believe that the lost Greek originals of the Tales of Solomon and Kitovras were the basis for the Celtic tales of King Arthur and the wizard Merlin. In the British Isles, Byzantine stories were translated and reimagined in their own way.

Battle of Centaurs and Wild Beasts. 2nd century/Wikimedia commons

What to read

Bas-relief in the Saint George Cathedral in Yuryev-Polsky, Russia, 1230–1234