The image of a she-wolf nursing a human child is one of the oldest images in the culture of the world. Come with us and explore how and why ancient people worshipped the she-wolf.

Most nations in the world have some version of the cult of the ancestral animal—the history of religions calls this belief system totemism. The tribes of Asia, Australia, the Americas, Africa, and Europe worshipped animals that were considered the ancestors of the tribe in remarkably similar ways. People honored the skulls of these animals, treated their hides as sacred objects, fell into a trance and spoke to the spirit of the ancestral beast, and any appearance of the animal in the vicinity was considered an important event with possibly significant consequences. Even today, it is rare to find a state emblem without a representative of the animal kingdom—lions, eagles, and horses have made their way from mythology to heraldry.

Proposed design of Turkey's emblem / Wikimedia commons

It would be wrong to think that only mighty and impressive animals can be made into totems. We often see that tribes worshipped very ordinary creatures: there were some that considered snails, frogs, and gophers their ancestors. Suffice it to recall that Achilles, one of the greatest heroes of ancient Greece, was the leader of the Myrmidons, a people whose totem animal was an ant. And the god Apollo, among his many titles, was also called ‘Smintheus’ (meaning ‘mousy’), for that was the totem of the people amongst the first to worship Apollo, thus associating him somewhat with their venerable ancestor, the mouse. However, ‘Lykaios’ (‘of the wolf’) is also among other names of Apollo. But since mice are mice and ants are ants, the most popular totems in the ancient world tended to be more serious animals.

The Cretan-Mycenaean pantheon tended to honor the bull, the Celtic pantheon to the deer, and the Germanic-Slavic pantheon to the bear. But the Turkic community and the Romans converged in their tastes—the main totem in both cultures was the wolf. Strong, fearless, intelligent animals, different from bears in their ability to live together, to sacrifice themselves to protect their loved ones—the wolf was a very attractive ancestral image.

Raven and wolf totem inside the Klemtu big house/Alamy

Apart from the Turkic peoples and the ancient Latins, we can also find a rather powerful cult of wolves in some regions of India, among some Slavs, and sometimes among the Germans.

As we know, a totem is first of all an ancestral animal; ancient peoples perceived it not only as a spirit, a guide, and a protector but also as their actual biological ancestor, who once happened to produce a human being. Later, of course, this idea was reinterpreted by people who had learned to understand the theory of reproduction and conception a little better. More often, mature myths of animal progenitors tell of human babies who are abandoned or lost and then nourished by the milk of a good-hearted she-wolf. For example, take the story of the twins who founded Rome, Remus and Romulus. They were born to a vestal princess impregnated by the god Mars. The princess, reasonably fearing a terrible execution for having an illegal pregnancy (vestals were supposed to be virgins throughout their term of service), took the babies into the forest. And that was the moment when the true, gray, and fanged mother of the Roman people appeared on the scene.

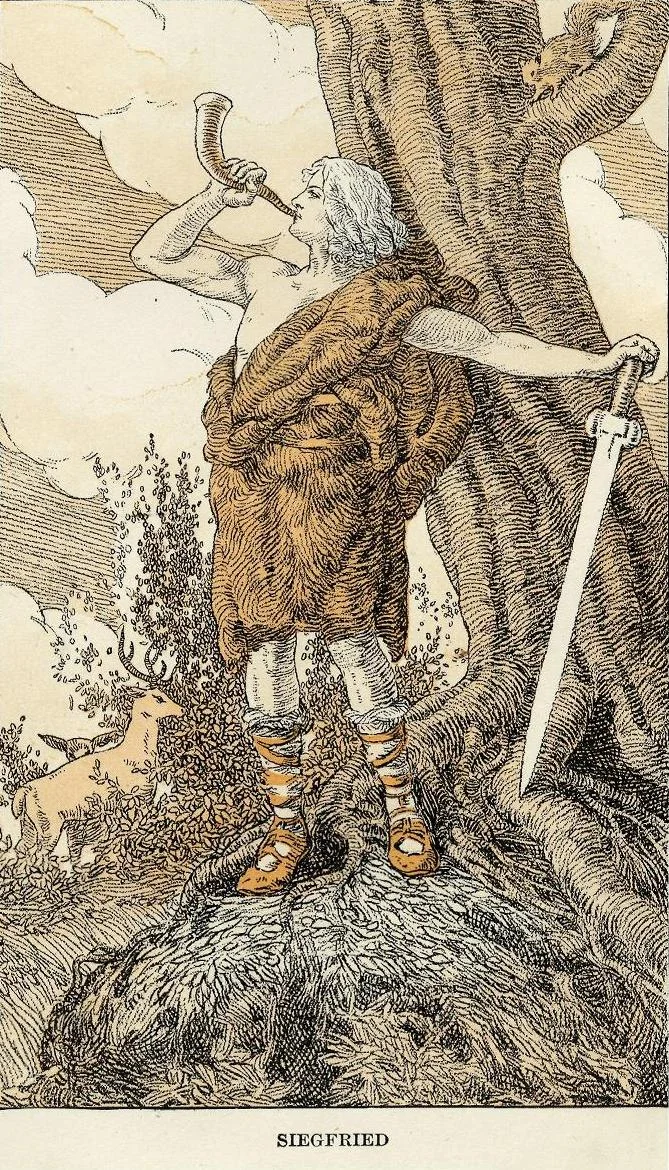

The influence of the wolf can also be seen evident in Sigmund, one of the heroes of the Germanic-Scandinavian epic Nibelungenlied. In the later version of the myth, his shapeshifting mother turns into a wolf, licks him, and Sigmund himself, wearing a wolf’s skin, becomes a werewolf. These are definitely remnants of the old totemic beliefs.

Siegfried and the Twilight of the Gods by Richard Wagner, illustrated by Arthur Rackham 1911/Wikimedia Commons/ Wikimedia Commons

Of course, the image of the mother wolf is most vividly represented in the mythology of the Turkic peoples, and this all-Turkic myth is incredibly dramatic. According to it, there was once a small tribe, no more in size than a large family. Some versions of the myth say that this tribe was one of the clans of the Huns. And so they were brutally wiped out by enemies. Only one boy, Asena, survived, who had his legs and arms cut off and was left to die. But the child was saved by the blue she-wolf Kok-Boru, who found the wounded child, dragged him into her lair, licked his wounds, and fed him what she had caught. When the boy grew up, the she-wolf gave birth to ten sons, from whom all the Turkic peoples are descended. This myth is widespread, from Beijing to Istanbul, and is known to all Turkic peoples, many of whom use the image of the blue she-wolf in their emblems.

Vasily Ushnitsky, a researcher of Turkic mythology, writes: ‘According to ancient Turkic legends, the ancestor of the Turks, Asena, was raised by a she-wolf; the hero’s descendants came from the Altai Mountains to the vast steppes and became the creators of the nomadic state … These genealogical legends link the ethnogenesis of the ancient Turkic people with the ancient Wusun and the Saka/Scythians.’

A 5-lira banknote from the Atatürk era in Turkey/Wikimedia Commons

Can these myths have any basis in fact? Could a she-wolf ever have nursed a human child? Let’s face it, though, Romulus and Remus didn’t stand a chance. Even assuming that a newborn could attach itself to a wolf’s teat without help, the she-wolf simply doesn’t produce enough milk to nurse a human cub. After all, lactation in wolves lasts no longer than six weeks, by which time the pups are firmly on their feet and ready to eat meat.

One of the mosaics on the floor of Vittorio Emanuele Gallery, representing Rome (the she-wolf and Romulus and Remus)/Shutterstock

In general, no one in the animal world is capable of such a feat—nursing a human newborn—except perhaps the great apes, and even that is purely theoretical.

All known (extremely rare!) cases of ‘feral’ children raised by animals, even those not considered falsified today, are not stories of infants, not even of very young children; they would be at least three or four years old. Deprived of parental care, they came into contact with animals (mostly dogs and occasionally monkeys) in one way or another, lived among them, lost the ability to speak, but still ate whatever they could get near human settlements (from vegetable gardens or garbage heaps or the food left by sympathetic neighbors, et cetera).

The existence of any real Mowgli has not yet been proven. But the image of a teenage boy who, for one reason or another, remained virtually alone, tamed a young female wolf, hunted with her, found brides, and then became the founder of a large family is not at all at odds with biological logic. On the contrary, it is well supported by modern anthropology.

Nicholas Roerich. Witchers. 1905 /Wikimedia Commons

Throughout human history, canine species have indeed protected, guarded, and kept our ancestors warm, helping them survive. In her book The Invaders: How Humans and Their Dogs Drove Neanderthals to Extinction, the famous paleoanthropologist Pat Shipman has even convincingly demonstrated that Homo sapiens was able to win the confrontation with other human species only thanks to dogs—domesticated and semi-domesticated wolves—who provided our main ancestors with fantastic advantages: the animals tracked prey, warned of danger and, most importantly, helped to stay warm at night. Live warmers with a body temperature of 39 degrees Celsius gave Homo sapiens the ability to survive during minor ice ages. The specificity of the Homo sapiens brain made it possible to tame animals and find a common language with them, while Neanderthals and other proto-human species were apparently incapable of such feats of socialization.

So, unlike the lion and the bear, who see the human being as nothing more than a two-legged treat, the mother wolf indeed deserves her title.

What to read

1. В.В. Ушницкий, Генеалогические легенды древних тюрков-ашина: волчица и олень-лань в качестве тотемных предков. — Проблемы востоковедения. 2016.

2. Ю.А. Зуев, Ранние тюрки: очерки истории и идеологии. — Алматы: ДайкПресс, 2002.

3. Пэт Шипман, Захватчики: люди и собаки против неандертальцев. — Альпина, 2016.