Flowers of death

This was no hippie party in ancient Rome—it was instead a mass execution.

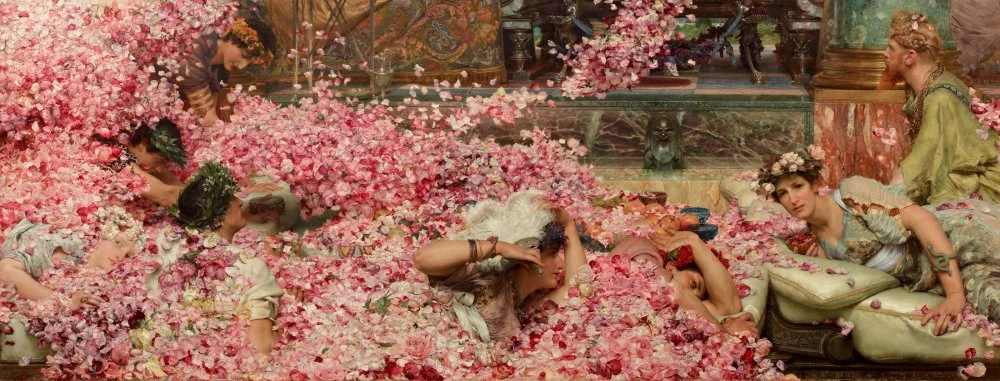

The Roses of Heliogabalus by Alma-Tadema (1888)/Wikimedia commons

The Roses of Heliogabalus by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1888)

This painting is in a private collection.

The story of Emperor Heliogabalus smothering his enemies with rose petals is likely an invention of imagination. This painting shows us how ancient pasquils, rumors of a sort, and Victorian myths found each other.

This stunning and rather large (132 x 213 cm) canvas is unmistakably the work of the beloved Victorian painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Despite being somewhat overlooked in the annals of art history, he is regarded as one of the many salon masters of the late nineteenth century, producing an abundance of rich and appealing paintings centered around ‘historical themes’. These works, with their meticulous attention to detail, portrayal of beauty, dramatic narratives, striking attire, and more, delighted the bourgeoisie.

Lawrence Alma-Tademа (1870)/Wikimedia commons

Yet, the legacies of certain artists undergo reinterpretation over the years. The noble veneer of time prompts their somewhat obscure names to resurface. And this is precisely the case with Alma-Tadema, whose nearly forgotten works have been steadily regaining interest over the past two decades. One of his most famous works is The Roses of Heliogabalus. In the painting, we see the Roman emperor Heliogabalus (218–222 CE) enjoying the view of a banquet hall from a balcony, surrounded by family and friends, as it is showered with countless pink rose petals. The bodies of other revelers lie beneath the cascade of petals, including a Gallic warrior with golden hair and a heavy necklace.

The Roses of Heliogabalus by Alma-Tadema (1888)/Wikimedia commons

As per the conventional interpretation of the painting, all the captives of the roses are moving from a state of blissful intoxication to a deadly slumber. The scent of roses suffocates them as the flowers consume oxygen, leaving only their poisonous vapors to use for breathing. The emperor, adorned in a tiara and golden toga, scrutinizes the faces of the dying with keen interest while his table companions, including his mother, observe the demise of their adversaries with contented indifference.

It is commonly believed that the subject of the painting is taken from Roman History by Dio Cassius or from the Historia Augusta (Augustan History) Biographies of the Emperors, a collection of stories about Roman emperors that was presumably compiled in the third century CE.

Heligabalus/Wikimedia commons

Dio Cassius makes no mention of banquets with roses in his work. However, though Aelius Lampridius, the author of the story about Heliogabalus in the Augustan History, mentions the emperor's fondness for these flowers, he does not speak of roses as a murder weapon, saying, ‘He carpeted the dining rooms, beds, and porticoes with roses and strolled among them.’ He also describes the emperor’s love for the blooms thus: ‘… He filled the ponds with wine infused with rose petals and bathed with his companions.’

As for violets, the emperor did overwhelm his guests by filling closed rooms with flowers to the point that sometimes people couldn't escape the premises. Incredibly, he did this as a joke and not as a way to extract vengeance of any sort: ‘In his dining rooms with retractable ceilings, he buried his sycophants under such a quantity of violets that some, unable to rise, suffocated and perished.’ In other words, they mechanically suffocated in the flowers and perished under their weight. This method of execution seemed unbelievable but it was one that the Victorians understood well.

Detail depicting the victims of Heliogabalus/Wikimedia commons

In fact, the concept of the ‘deathbed of flowers’ isn't an ancient Roman creation but rather a timeless urban legend from the nineteenth century. During this era, Victorians believed that the overpowering scent of flowers could be lethal. It is true that if a room were filled overnight with an incredible number of bouquets, one could wake up with a severe headache because plants, even when cut, absorb oxygen and emit carbon dioxide at night.

Yet, picturing a room both so tightly sealed and filled with such an abundance of flowers causing death in such a convoluted manner is difficult to imagine—unless the individual was asthmatic and allergic to pollen. However, in such a scenario, the cause of death wouldn't be carbon dioxide but rather anaphylactic shock triggered by an allergic reaction to pollen.

The girls look at the dying with pleasure. Fragment/Wikimedia commons

But in the nineteenth century, the newly understood concept of gas exchange in plants, popularized by contemporaries to the broader public, gave rise to many legends about beautiful princesses, singers, and actresses who carelessly fell asleep surrounded by sent bouquets and never woke up again.

The apotheosis of this legend was the 1875 novel by Emile Zola, The Sin of Father Mouret, where the heroine, Albine, ends her life by falling asleep on a bed of flowers:

… She was lulled by the descending scale of violets, which slowed down and drowned, turning into the delightful singing of heliotrope, smelling of vanilla, and heralding the approach of the wedding. Occasionally, the night violets tinkled with barely audible trills. Then silence reigned for a while. And now the orchestra of breathless roses joined in … Clutching her hands tighter to her heart, languishing, gasping convulsively, Albine was dying. She opened her mouth, seeking the kiss meant to suffocate her—and then hyacinths and tuberoses breathed, enveloping her in their intoxicating breath, so loud that it covered even the choir of roses. And Albine died with the last breath of the withered flowers.

The story of Heliogabalus suffocating guests to death with flowers merged with this urban legend, and this murderous image of the emperor became immensely popular for a while. And it wasn’t only Alma-Tadema who paid tribute to the ruler. We may remember, for example, the painting Buried in Flowers (1886) by P.A. Svedomsky.

P.A. Svedomsky. Burial in Flowers/Wikimedia commons

We should also remember here that Heliogabalus was no stranger to vile insinuations. This boy, emperor for only four years and brutally murdered shortly after his eighteenth birthday, has been an example of a corrupt ruler for almost 2,000 years. He’s often mentioned alongside Caligula, Nero, and other unsuccessful contenders in the struggle for supremacy and power in Rome. We don’t actually know any truths about him.

First of all, he was never called Heliogabalus. His name was Varius Avitus Bassianus, and when, after a long search for a suitable heir, he was finally made emperor of Rome at the age of fourteen, he was given another name—Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. He was called Heliogabalus because his maternal great-grandfather served as a priest in one of the Syrian temples of Elagabalus, the sun god. The boy's family revered their customary deity, and there was a small temple to this god in Rome. When the young man came to power, he ordered an increase in the funding for the temple and its refurbishment.

Marble bust of Roman emperor Elagabalus, ca. 221 AD, Capitoline Museums/Wikimedia commons

And that is all we know about ‘Heliogabalus’. All the other information provided by Dio Cassius is merely traditional, standard gossip about defeated Caesars. They were all alike: sodomites, spending all their time in brothels, pursuing married women, having relations with their own sisters, and corrupting Vestal Virgins. They also sacrificed boys from noble families at the altar, indulged in strange delicacies like ‘a handful of camel brains, flamingo brains, and parrot heads’, and performed licentious dances in the blood of their victims.

Considering that Dio Cassius wrote his history under the patronage of Alexander Severus, who ordered the murder of Heliogabalus and his mother, it would be strange to expect anything else from him. As for the Augustan History, the pages dedicated to Heliogabalus contain blatant pornography of such a fantastical nature that nobody has ever attempted to consider this work a serious historical source.

So, in actual history, Heliogabalus appears before us as a teenage boy, entirely obedient to his mother and grandmother. After the political downfall of these women, he was barbarically mutilated and slain along with his mother on 11 March 222 CE. His murderer, Alexander Severus, became emperor and ensured that historians ‘correctly’ depicted the slain ruler in their writings