The widespread tea consumption we see in Central Asia today was firmly established only relatively recently. However, the beverage itself has been part of our ancestors’ lives for quite some time, and the Kazakh steppe was known far beyond the region, thanks to tea.

- 1. When Tea Appeared in Central Asia

- 2. Tea and Horses: How the Steppe Became Part of the Ancient Tea-Horse Road

- 3. From Monopoly to Free Trade: Tea Between China, India, and the British Empire

- 4. The Kazakh Steppe: A Trade Corridor Between East and West

- 5. Tea in the Steppe: An Integral Part of Kazakh Life

When Tea Appeared in Central Asia

Refined tea first reached Central Asia in the seventh century, during the height of the Tang Empire (618–907). Around that time, tea houses—places where people could immerse themselves in the culture of tea drinking—began to spread from the area of present-day Afghanistan to Korea.

People preparing tea. Mural in the tomb of Zhang Kuangzheng, Xuanhua, Hebei, Liao Dynasty, 1093-1117 / Pictures From History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

During the same period, tea in the form of compressed bricks became a full-fledged currency along the caravan routes of the Great Silk Road.

Tea and Horses: How the Steppe Became Part of the Ancient Tea-Horse Road

For centuries, the Chinese prized nothing more from Central Asia than the region’s horses. Swift, strong, and enduring, these steppe-bred animals were worth their weight in gold, coveted as much for their beauty as for their unmatched stamina on the battlefield. So, unlike the northeastern borderlands, where horses were traded for silk or silver, China’s northwestern borders saw the development of a full-scale trading system where horses were exchanged for tea.

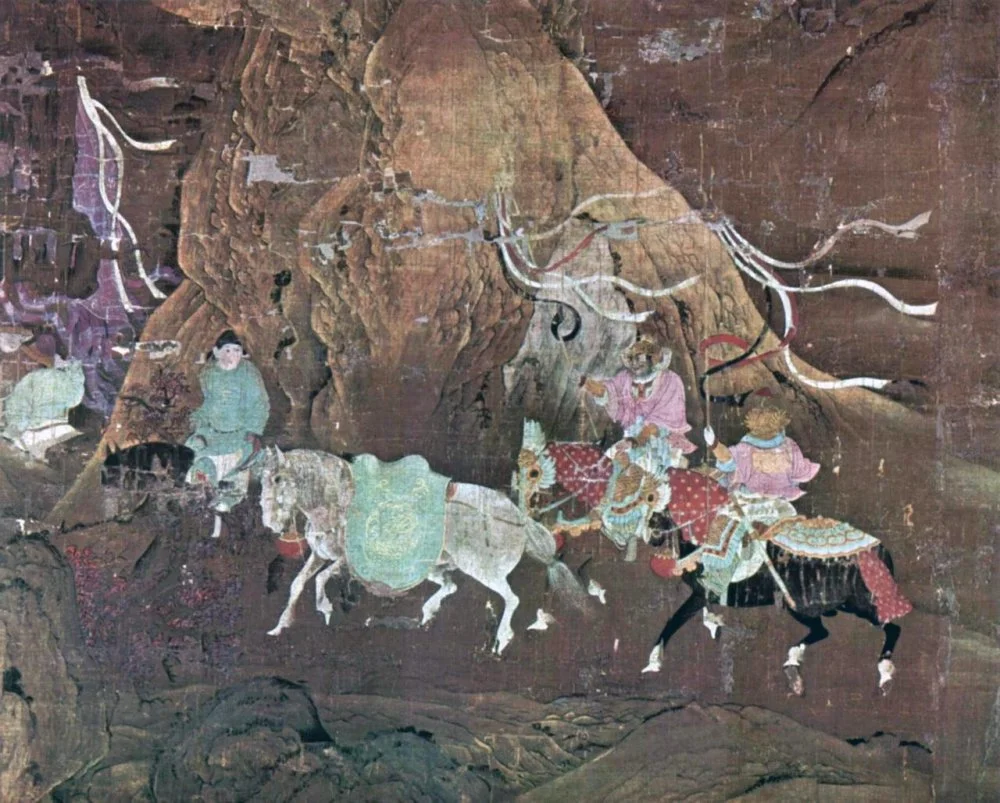

The Tea Horse Road (Cha Ma Dao). A tributary horse for Emperor Xuanzong. Song Dynasty, 12th century / Pictures From History / Universal Images Group via Getty Images

This trade was already flourishing during the Song Empire (960–1279), and in the twelfth century, China even established a state office to oversee horse trading. Thus, nearly 1,000 years ago, our ancestors had exclusive access to tea supplied by a state-run monopoly, and paid for it with their most valuable asset.

From Monopoly to Free Trade: Tea Between China, India, and the British Empire

Over time, state control over tea exports from China gradually weakened. Private merchants stepped in, and competition increased as more tea-supplying countries entered the international market.

Central Asia Trade Report. 1864 / Parliamentary Papers. Volume 42

In an effort to reduce its financial dependence on Chinese tea exports, the British Empire began actively cultivating tea in India, and this tea was also exported to Central Asia. The Kazakh steppe—and the Kazakhs themselves—became part of this international trade network, their role significant enough to be discussed in the British Parliament, as noted in the Parliamentary Papers of 1864.

The Kazakh Steppe: A Trade Corridor Between East and West

Central Asia’s access to the tea markets of China, India, and Persia, combined with the ease of transporting tea across the region, made it especially attractive to neighboring powers. At the heart of this trade were the Kazakhs, who, thanks to their right to duty-free commerce, played a pivotal role in carrying tea northward, connecting distant markets across vast stretches of steppe.

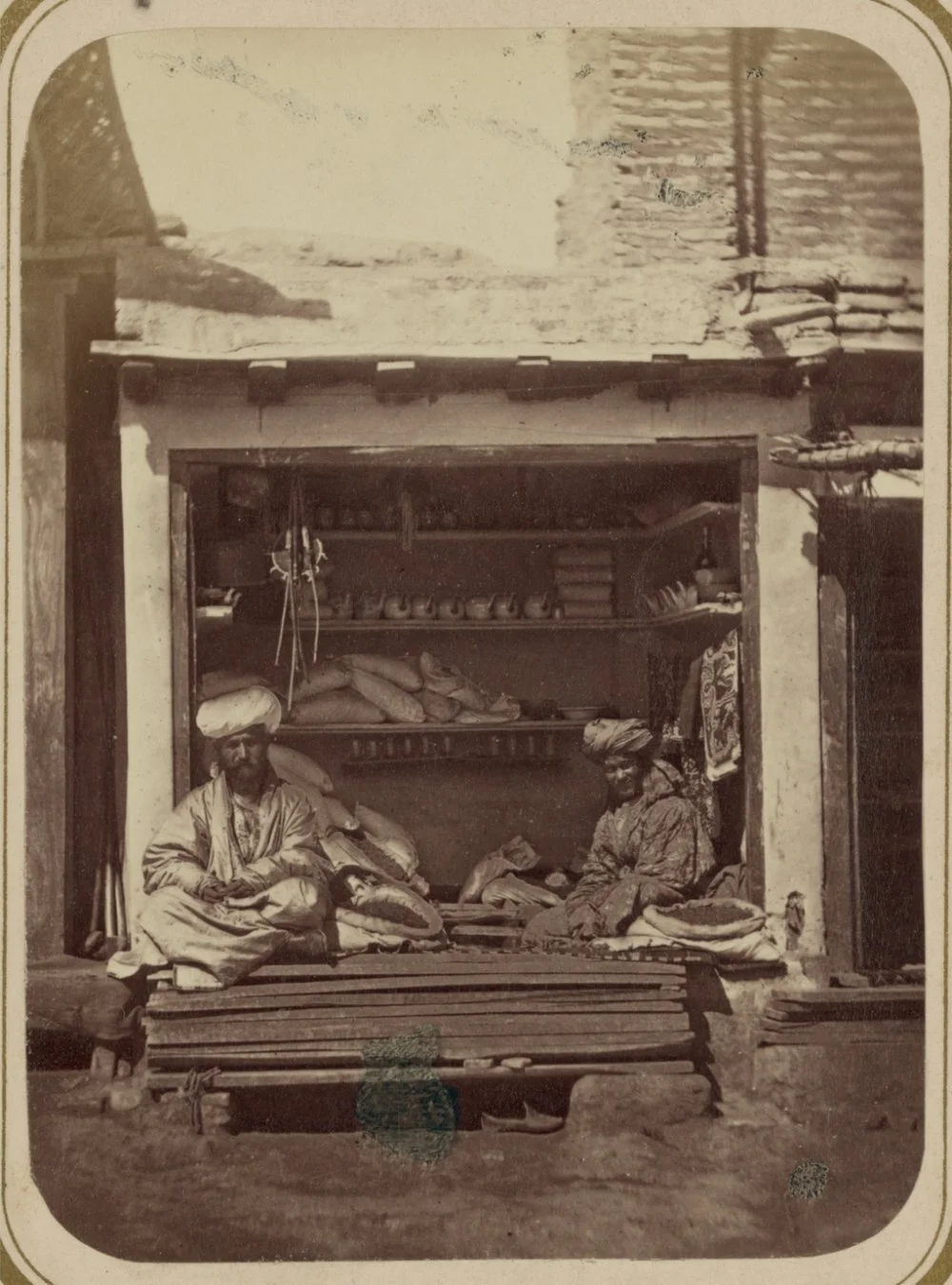

N. Nekhoroshev. «Tea Seller. Turkestan Album». Samarkand / Library of Congress

The Kazakh steppe featured prominently in nineteenth-century Russian trade reports and was often noted for its role in the tea trade. In 1855 alone, tea worth 450,000 rubles was imported into Russia through Kazakh territory. Renowned scholar and ethnographer Chokan Valikhanov also wrote about tea, highlighting the significance of Kashgar and other cities in Eastern Turkestan (now the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, China) in the global tea trade.

Tea in the Steppe: An Integral Part of Kazakh Life

Regardless of trade and economic trends, one thing remained constant—the love of the Kazkah people for tea. The well-known nineteenth-century German thinker Hermann Kletke described the Kazakhs’ passion for tea by saying:

‘They are ready to drink it in the fiercest cold and the most scorching heat, before and after everything, always and everywhere.’

In his essays on life in the Kazakh steppe, Russian official I. Mikhailov wrote:

‘Tea in the steppe is an invaluable gift from God. There, it is more important than bread. You can do without bread, living on meat alone. But tea is irreplaceable.’

Thus, the beverage whose origins are claimed by both China and India became an inseparable part of Kazakh life, served at festive gatherings and family meals alike. In the harsh climate of the steppe, a steaming bowl of tea provided warmth and comfort, while its preparation and serving evolved into a ritual that reflected both tradition and social etiquette. Whether sipped inside the warm interior of a yurt after a long journey or shared among neighbors during communal celebrations, tea became more than just a beverage: it was a symbol of welcome, a thread linking the Kazakhs to the great caravan routes of history, and a lasting reminder of the region’s place in the crossroads of cultures.

Milk tea / Alamy